189 Thermal Burns

• Many patients who initially appear to have a mild airway burn injury still require early intubation because critical edema will develop. Intubate; do not observe.

• Extremely high doses of narcotics (three to five times normal) are usually required to control pain in patients with severe burns.

• Patients with severe burns have large fluid requirements, which are best determined initially by standard calculations.

• The best measure of adequate fluid replacement is urine output.

• Cold water can help relieve the pain of first- and second-degree burns, but patients with significant burns involving more than 9% of their total body surface area should not have cold applied.

• Burn centers have improved mortality rates, so transfer to a burn center should be considered early in the patient’s management.

• Empiric oral or intravenous antibiotic administration is not indicated, but topical antibiotics are.

Epidemiology

Approximately 500,000 patients sustain nonfatal burn injuries in the United States each year.1 Only 6% of these patients require hospitalization, so most are treated as outpatients.

Pathophysiology

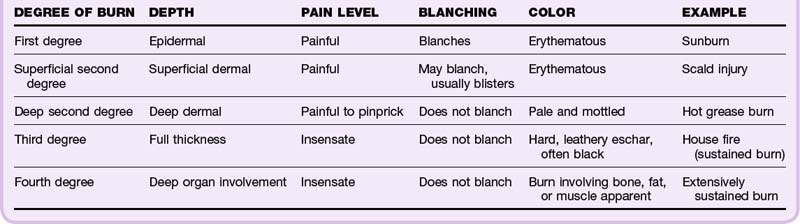

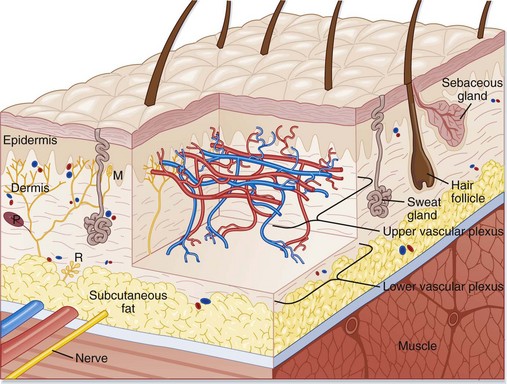

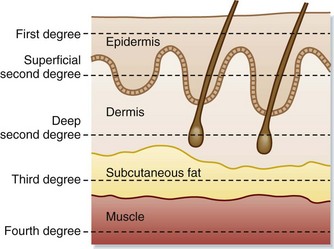

Knowing the anatomy of the skin is essential to understanding burn pathophysiology (Fig. 189.1). Burns are classified according to the depth of injury (Table 189.1 and Fig. 189.2). First- and second-degree burns are partial-thickness burns and have a better prognosis. Full-thickness burns (third and fourth degree) are insensate and require skin grafts (unless <1 cm) or reconstruction because of destruction of the epidermis and dermis. Based on the depth of the burn, the ability to heal can be predicted. Because the dermis itself is the living tissue, the depth of burn into the dermis determines how likely wounds are to heal and what degree of scarring can be expected.

Fig. 189.1 Schematic representation of a cross section of human skin.

(From Adkinson NF, Yunginger JW, Busse WW, et al, editors. Middleton’s allergy: principles and practice. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2003.)

Fig. 189.2 Depth of burns.

(From Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, et al, editors. Sabiston textbook of surgery. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Frequently, occupational exposure causes burns. Direct contact with flame, scalds, injuries caused by heated equipment or arc welding, gasoline fires, and cooking accidents are all common. In children or elderly patients with burn injuries, the concern for abuse is always present (see the “Red Flags” box).

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Burns inconsistent with the mechanism: concerning for nonaccidental trauma or abuse

Circular burns consistent with cigarette butt burns

Burns on the lower extremities without burns on the soles: consistent with forced immersion scald burns

Any perineal burn (area not exposed during normal activities)

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

In each patient with a burn, the airway is still the most important component. Burn victims are often also subject to smoke inhalation or thermal injury to respiratory tissue from superheated air, and these injuries take priority over any others. Carbon monoxide, cyanide, and other inhaled toxins should be considered. The most threatening injuries are deep burns, burns covering a significant proportion of body surface area, and respiratory burns (Box 189.1).

Box 189.1

Criteria of the American Burn Association for Referral to a Burn Unit

Partial-thickness burns involving greater than 10% total body surface area

Burns that involve the hands, face, feet, genitalia, perineum, or major joints

Third-degree (full-thickness) burns in any age group

Electrical burns, including lightning injury

Burn injury in patients with preexisting medical disorders that could complicate management or recovery or could affect mortality

Patients with concomitant burn injury and trauma in which the burn injury poses the greatest risk for morbidity or mortality

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree