Fig. 24.1

Diagram from the 9 January 1847, issue of The Illustrated London News, showing the apparatus used for several anaesthetics in London during December, 1846. Both Belisario and Pugh are said to have copied their apparatus from this diagram. (Courtesy of R. Westhorpe.)

The “January Mail” for New Zealand reached Wellington on board theWaterwitch, on 4 July, 1847. On 7 July, the Wellington Independent reported “It appears by the London papers that the use of Sulphuric Aether, inhaled by vapour, by patients about to undergo painful operations, has reduced them to a state of unconsciousness while the operations were performed. Cases are given in which the most serious operations were performed without causing pain to the patient”.

The First Anaesthetics in Australia

On 7 June 1847, William Pugh (Fig. 24.2) administered ether for surgery in Launceston, Tasmania, and John Belisario (Fig. 24.3) gave ether for dentistry in Sydney. Both Pugh and Belisario based their apparatus on the sketch in the Illustrated London News. In the Sydney Morning Herald, 8 June, 1847, below a list of auction sales, there appeared: “Painless Surgery’We had an opportunity yesterday of witnessing, at Mr Belisario’ s, the extraction of teeth from persons who had inhaled ether, and in two cases the effect was as described in recent papers from England, almost miraculous….”

Fig. 24.2

William Pugh, general practitioner of Launceston, Tasmania, who administered ether for 2 surgical operations, on 7 June 1847. (Courtesy Geoffrey Kaye Museum of Anaesthetic History, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, Melbourne.)

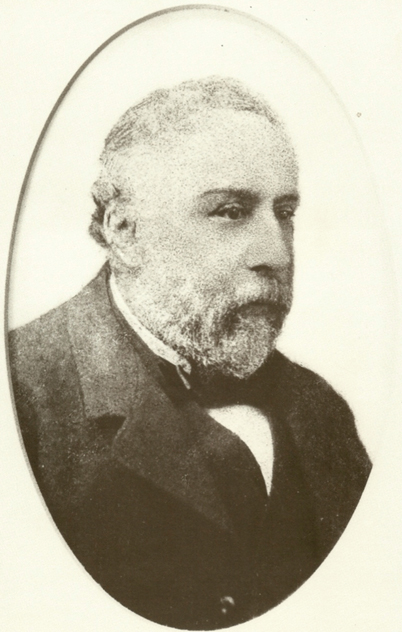

Fig. 24.3

John Belisario, dentist of Sydney, who used ether for dental extractions on 7 June 1847. (Courtesy Geoffrey Kaye Museum of Anaesthetic History, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, Melbourne.)

Further, on 16 June, the Herald published:

“…In the first case, a Mr Yarrow inhaled by means of a tube communicating with a vessel containing the ether, until from the entire relaxation of his whole frame, and the deathly expression of his physiognomy, we began to apprehend that the proceedings were taking a turn towards manslaughter, and that our curiosity was leading us into a scrape. As soon as Mr Yarrow was fairly off, as it was called; that is, as soon as his eyes closed, his arms dropped and his body fell back as he sat…the tube was withdrawn from his mouth, and several persons in the room proceeded to satisfy their curiosity upon the patient, each in his own way. One pinched him in the arm, another in the leg, a third squeezed the top knuckle joints of the patient’s hand violently together…but the patient gave no sign whatever of the sensation.”

The report continues:“….He concluded by asking like Oliver Twist ‘for more’, which however was not given to him, as another patient stepped in…” This patient had two painful decayed stumps removed while under the influence of ether, and interestingly, “he had on a previous occasion undergone…extraction under the ether application….” When and where had this patient had his previous anaesthetic? Was it in Sydney, or in England’the mystery remains?

Pugh probably obtained the ‘Illustrated London News’ on 29 May via coach from Hobart where theLady Howden had berthed on 27 May. This gave him time to prepare the ether and apparatus, and plan the surgery. He also had willing patients who had previously undergone unsuccessful attempts at surgery. He proceeded to give two successful ether anaesthetics at St John’s Hospital, in the presence of an audience that included the editor of the Launceston Examiner.

So, both Belisario and Pugh gave anaesthetics on 7 June 1847, but who was first? Belisario may have used ether previously, but no record has been discovered. He reportedly performed anaesthesia on 40 patients by 9th June, his successes leading him to advertise his services in the newspaper. David Thomas performed anaesthesia in Melbourne on 2 August, followed by Benjamin Kent in Adelaide on 30 September.

The First Anaesthetic in New Zealand

The first anaesthetic in New Zealand took place on 27 September 1847. That morning, Dr. John Fitzgerald and Mr. James Marriott went to the Wellington Gaol,“where a prisoner was anxious to have a decayed tooth extracted”. Marriott was an engraver with a talent for constructing mathematical and scientific instruments. He had constructed an inhaler for ether, although the particulars are not known [8]. Marriott administered the ether, and Fitzgerald extracted the tooth. That afternoon, Fitzgerald removed a fibromatous lesion of the shoulder from Hiangarere, a Maori chief, at the Colonial Hospital. Marriott was the anaesthetist, and several Maori tribesmen observed the operation [8].

Good News?

Was anaesthesia welcomed? Recall that the public in general and the medical profession in particular, considered that pain and surgery were inseparable partners.

On 7 June, Pugh wrote to the recently establishedAustralian Medical Journal which published his letter on 18 June:

“As it may be of interest to your readers to receive local testimony in addition to the published reports of cases, in which surgical operations have been divested of the usual suffering attendant on such procedures by the use of ethereal inhalation, I beg to furnish you with the results of a trial of this novel discovery made at St John’s Hospital today, the results which, although to a certain extent incomplete, were so far so satisfactory as to justify an opinion that large amount of suffering hitherto experienced by the patients may be superseded, and that many operations can be performed during the stage of unconsciousness which is so readily induced.”

“I employed part of Nooth’s apparatus in the manner delineated in the illustrated London News of the 9th (January) and I found it in every respect suited to the purpose.”

The Journal responded with a long editorial that included: “…we have no hesitation in predicting for this process a transient popularity. It will have its day, ultimately to be abandoned as useless and/or injurious….”

The editor’s stance mellowed modestly in the next issue:

“Since our last publication, accounts of the effects of the sulphuric ether inhalation have poured in upon us from all quarters; and loud have been the blowing of trumpets and great the jubilation and overwhelming the nonsense uttered and invited thereupon…it may for a time serve interested parties as a medium for puffing themselves and for mystifying the public by enveloping the matter in a cloud of pseudo-scientific balderdash; but the simple fact is, that to inhale the sulphuric ether is neither more nor less than a mode of getting drunk;”

“Do not let us be misunderstood. We do not say that it ought entirely to be eschewed; all we contend for is that it should be used not indiscriminately, but with caution; and only under the superintendence of medical practitioners, who, instead of allowing themselves to be run away with by the novelty of the process, should use it and investigate its effects coolly and philosophically, so that it may not, if calculated to be really useful, come as many other therapeutic means have come to a premature end through the discredit thrown upon it by its abuse….”

Chloroform or Ether?

Ether was the sole anaesthetic used in Australia, until chloroform arrived. On 31 March 1848, the Sydney Morning Herald reported:

“We have now to state that a new anaesthetic agent has been discovered by Professor Simpson of Edinburgh. It is a substance called chloroform. It is applied similarly to ether, that is to say, the patient is made to inhale it, and the advantages over ether are so great, that it is said the latter will be entirely superseded.”

On 12 April, 1848, the following report was published:

“Chloroform. This new agent, for rendering the operations of surgery painless, was yesterday, in the presence of some visitors, most successfully tried by the Surgeons of the Sydney Infirmary. The subject, a little girl had to submit to a most tedious, difficult and hitherto excruciating operation. Dr McEwan operated, Mr Nathan administered the anaesthetic.”

The Sydney Hospital surgeon who administered the anaesthetic was Charles Nathan, who had assisted Belisario in the first ether anaesthetics the previous year. Chloroform soon displaced ether as the agent of choice.

Gold was discovered in Victoria on 10 June 1851. By 1860, the non-indigenous population had more than doubled to exceed one million. Hundreds of the new settlers practiced medicine, many without qualifications. Most surgery was performed in makeshift surroundings, and chloroform was the most suitable anesthetic. Anesthesia required a dropper bottle, a handkerchief and a small volume of sweet smelling chloroform. And chloroform didn’t catch fire, a particular advantage in a tent.

The first patient death under chloroform was reported just three months after its introduction to Australia [7]. It was not until the late 1870s, that ether challenged the dominance of chloroform, and until 1900, the word “chloroformist” was synonymous with “anaesthetist”. Chloroform had other uses. An entry in the 20 September 1848 issue of the Sydney Morning Herald says “Chloroform is recommended as excellent for scolding wives. A husband who has tried it says’‘No family should be without it’”.

William Purdie, one of Simpson’s classmates, brought the benefits of chloroform to New Zealand. Purdie had been a regular attendee at meetings of the Obstetrical Society in Edinburgh, where he had commenced practice. Having arrived in New Zealand in late 1849, with a supply of chloroform, he set up practice in Dunedin [8].

Nitrous Oxide

Nitrous oxide emerged as an alternative, for dental surgery in particular, at about the same time as the re-emergence of ether. It must have been known in the early scientific circles of the colonies. In the Sydney Morning Herald of Monday, 21 July 1845, JS Norrie advertised his lecture on chemistry that evening on“The simple substances and the metals. At the conclusion of the lecture the effect of the laughing gas will be exhibited.”

There is no further reference to the use of nitrous oxide until Colin Buchanan of Port Stephens, wrote in July 1847 of his administration of ether for the repair of a popliteal aneurysm. He wrote “…not being aware of the kind of apparatus used for the inhalation of ether, I tried the simple bladder with mouthpiece, similar to what is used in the inhalation of nitrous oxide, or laughing gas, which answered the purpose admirably (I must tell you that I first tried it on myself, which convinced me as to its efficacy).” We presume that Buchanan used nitrous oxide for recreational purposes [7].

Recreational use of nitrous oxide appears in a contribution to the NSW Medical Gazette, a letter perhaps stimulated by the introduction of nitrous oxide into dental practice around 1870:

“Gentlemen… perhaps it would interest some of your readers to know the effects (nitrous oxide) produced upon me when taken on two different occasions, several years back. I inhaled it first in Sydney, at the residence of one of my friends.

“I had breathed about three quarts when the landlady of the house entered the room, and looked in an angry manner at me, to reprove me for being so ridiculous as to have the opening of a bullock’s bladder in my mouth, like the figures in an old fashioned caricature; this look and the gas together caused me to have a violent fit of laughing; I laughed in the chair that I was sitting on, then I fell on the floor and rolled over and over on the ground still laughing, and this state lasted about five minutes. I then recovered perfectly without any unpleasant after-effects. I believe however, I made an enemy of my friend’s landlady ever-afterwards as she never spoke to me again.”

“I am, gentlemen, yours sincerely, A subscriber.” Sydney August 20th 1870 [9]

In his “History of Dentistry in South Australia 1836–1936” Arthur Chapman writes that in the 1850s “the introduction of laughing gas must have been greatly appreciated by those able to avail themselves of it [10].” This presumably also refers to recreational use, because Chapman describes Lionel Blackmore, who arrived in Adelaide in 1870, as probably the first to use nitrous oxide for dental anaesthesia in Adelaide. The Sydney Morning Herald of 24 October 1870, reported that “Mr E Reading, Dentist, 128 Phillip Street, administers the nitrous oxide gas on Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.” By the end of the 1870s, Chapman notes that “we find gold, platinum and vulcanite in use for artificial denture bases, and nitrous oxide gas largely employed for extractions [10].”

The Australian Medical Gazette was the first Australian journal to include an article on nitrous oxide anaesthesia, in 1870 reprinting a paper from the 1869Lancet by Charles Fox, Dental Surgeon to the Dental Hospital in London. Having learnt techniques from Gardner Colton, his paper extolled the virtues of nitrous oxide anaesthesia, citing his experience of its administration to M. Blondin for “extremely severe dental operations” whereupon the patient “performed all his most difficult feats on the high rope 430 feet long within three hours after I had given him the gas [11].”

The NSW Medical Gazette of 1871 noted in the “Miscellanea” section, that nitrous oxide was likely to supersede chloroform for short operations [12]. However, for the remainder of the nineteenth century, medical journals scarcely mention nitrous oxide, although it continued to be used regularly by dentists (Fig. 24.4).

Fig. 24.4

Dental anaesthesia with nitrous oxide, in rural Australia (Colac) C 1900. (Courtesy of R. Westhorpe.)

The Adelaide based FH Faulding and Company, a pharmaceutical company founded in 1845, published Faulding’s Medical Journal.1 The quasi-scientific journal of news and reviews of scientific papers included advertisements for dental anaesthesia such as the “New York Dental Institute” of Grenfell Street, Adelaide, offering in the May 1900 edition “teeth extracted painlessly with Cocaine, Eucaine, Laughing Gas or Aether [13].”

Evidence of the establishment of local manufacture appears in the British Journal of Dental Science in 1898:

“Australian Nitrous Oxide Gas’In addition to making their own dentists, Australia is beginning to make its own nitrous oxide, for an Australian Nitrous Oxide Gas Company has been formed and a complete plant for the manufacture of the gas has been imported….The price will be lower than that of the imported gas, as the risk and expense of carriage as deck cargo is avoided, while the cylinders will be of uniform size. Advance Australia!” [14]

No record can be found of an Australian Nitrous Oxide Gas Company. If it was FH Faulding and Company, they didn’t mention it in Fauldings’ Medical Journal. Still, it is likely that they were manufacturing nitrous oxide by 1900, as they supplied apparatus and pre-filled cylinders according to advertisements in their journal.

Nitrous Oxide in New Zealand Before 1900

The story of nitrous oxide in New Zealand is similar to that in Australia. The December 1878 Napier newspaper reported: “Our Dentist, Mr H C Wilson, is about to commence the use of nitrous oxide (laughing) gas for producing insensibility to pain during dental operations… we believe that Mr Wilson is the first dentist in the Colonies who has introduced the use of this anaesthetic into his practice: and we must add that we are glad to see Napier taking the initiative in this advance of science.” [15]

Septimus Solomon Arthur Wellington Daniel Myers registered as a Dentist in 1880, and is thought to have introduced nitrous oxide in Invercargill. He then established a dental company in Dunedin, opening a Christchurch branch in 1888 [16].

An issue of stamps in 1893 with advertisements on the back indicates the expansion of nitrous oxide in New Zealand. Denominations ranged from one penny to one shilling, each stamp in a sheet bearing a different advertisement. The one advertising S Myers and Company noted that painless extractions are available using nitrous oxide gas. These stamps were withdrawn soon after issue due to a rumor that the ink, when licked, was injurious to health [16].

Deaths Under Chloroform

By 1870, the words anaesthesia and chloroform were virtually interchangeable. The deaths reported each year from 1848 had little influence on practice [17].

The July 1868 Australian Medical Journal, described a previously healthy 33 year old woman receiving chloroform at the Melbourne Hospital for surgery to her anal fistula and haemorrhoids. In the absence of the resident House Surgeon or Physician, the attending surgeon administered the chloroform. The patient struggled and died shortly thereafter. Although post mortem examination did not reveal the cause of death, kidney disease or impure chloroform was implicated. It was recommended that the hospital appoint a full-time chloroformist. The proposal went unsupported [18].

In February 1891, the Australian Medical Journal reported another death in a patient receiving chloroform at the Melbourne Hospital with the City Coroner recommending“…that there ought to be some specially qualified gentleman in the hospital for the administration and teaching of the use of chloroform.” The suggestion was put to the Medical Staff Committee who took no action [19].

In May 1891, a young man of 32 died during chloroform administration at the Melbourne Hospital. The “resuscitation” over 20 minutes included artificial respiration, hypodermic injections of ether, and intravenous ammonia. At inquest, the City Coroner declared that an expert should supervise chloroform administration.“It appeared to him, that cases of death under chloroform occurred far too frequently at the Melbourne Hospital. Students were allowed to give chloroform without any supervision. The wonder was not that deaths should occasionally occur, but that they did not happen more frequently [20,21].”

In an editorial entitled“Anaesthetics at the Melbourne Hospital”, the Australian Medical Journal argued for the appointment of a specialist anaesthetist to administer chloroform and other anaesthetics, and to supervise and instruct residents in the practice of anaesthesia. The Melbourne Hospital Medical Staff dealt with the issue by passing motions of confidence in whoever administered the chloroform [22,23].

At this time, physicians (internists) controlled most medical affairs, with surgeons not far behind and exerting increasing influence. Anaesthetists ranked poorly, anaesthesia being entrusted to junior staff or students. But when things went wrong, it was a problem with the patient or the chloroform, and not the administration or the administrator.

Non-Medical Anaesthetists

Non-medical anaesthetists gave many anaesthetics, particularly in rural Australia. The medical profession condemned such practices but did nothing to remove the problem by advancing the establishment of anaesthesia as a specialty.

In 1884, the Australasian Medical Gazette reported that a patient had died while receiving chloroform at Tamworth Hospital in central NSW. Mr Goodwin, a local chemist, had administered the chloroform. The journal asked why the surgeon, Eustace Pratt, did not use the anaesthetic services of another medical man. In the next issue, Pratt attacked the editor for his audacity, and chastised him for forwarding copies of his editorial to the local Tamworth papers and several prominent citizens. He described how“hundreds of men, not legally qualified, have to give chloroform in the bush.” He described the Medical Gazette as a moribund and poverty stricken organ of a small clique of mutual admirers [24,25].

Chloroform was easy to administer with a minimum of equipment. The status of the chloroformist was negligible, and surgeons regarded their anaesthetists as dependents rather than colleagues. Nonetheless, non-medical anaesthetists gradually disappeared, and by 1900, hospital residents or family doctors, gave virtually all anaesthetics. Until the mid-twentieth century, the family doctor who referred a patient to a surgeon would commonly provide the anaesthesia.

1900’the Beginnings of a Specialty

In 1901, the Legislative Council considered a Dental Act which would establish a Board registering Dentists with appropriate qualifications and would permit only those holding the Diploma of one of the American or British Dental Colleges to administer nitrous oxide. In November, Faulding’s Medical Journal commented that

“it can hardly be claimed that (this) provision has been inserted for the benefit of the public, for it means that to less than one dozen dentists in South Australia is granted the sole right to administer this anaesthetic. The members of this privileged class are all with high class practices, who charge high fees. It is therefore obvious that the poorer classes will be practically denied the comfort and benefit of nitrous oxide when undergoing dental operations…”

In 1909, four honorary anaesthetists were appointed to the Melbourne Hospital, to instruct and supervise residents. The resident doctors, who covered all disciplines during their work, had to view 20 anaesthetics before attempting one. Although this was a major step forward, the honoraries did not normally attend cases out of hours, when residents provided anaesthetics. This led to a furore after a death in September 1912.

An extremely ill 66-year-old man presented for surgery at 6am. The unfortunate duty resident administered ethyl chloride and ether, whereupon the patient immediately succumbed [26]. One of the honorary anaesthetists, Rupert Hornabrook (Australia’s first full-time specialist anaesthetist, and an advocate for the ethyl chloride’ether sequence) made a personal representation to the Coroner, leading to a public enquiry. Hornabrook argued that residents should not have to deal with such cases, and that a senior anaesthetic resident should always be present. He proclaimed,“Anaesthetic work should be more respected than it was.” The Coroner added fuel to the fire by stating“there appeared to be a feeling among medical men that the anaesthetist’s work was not as necessary as some might think.” The hospital was outraged, claiming that Hornabrook’s action was disloyal to the hospital and to the residents [26–28].

In the March 1914 Australian Medical Journal, Hornabrook wrote“The anaesthetist should be placed on the staffs of hospitals… on equal footing with other members of the staff. It is useless to expect good men to come forward unless they are given some status .” [29]

But things didn’t change. Physicians and surgeons controlled public hospitals. Surgeons depended on referrals from general practitioners in their private practices, and often engaged those practitioners as assistants or anaesthetists. Surgeons may have wanted anaesthetists to provide services, but they were not prepared to give them more than a passing acknowledgement. The traditional relationship between the surgeon and the “chloroformist” was hard to break, and the idea of the surgeon collecting the fee on behalf of the anaesthetist was firmly entrenched.

Thus, competing factors influenced the establishment of specialist anesthetists. There was tacit recognition of the desirability of specialisation, but difficulty in attracting doctors into anaesthesia because of low status and poor remuneration. Their paltry remuneration forced anaesthetists to rely on activities such as general practice to survive. They had no time for research, and they were not unified.

There were exceptions. Edward Embley championed the cause of anaesthetists. He had gained worldwide recognition for determining that the cause of death from chloroform was cardiac and not respiratory [30]. His suburban general practice supported his unpaid weekend research at Melbourne University.

Hornabrook, recognised for his enthusiasm in experimentation (Fig. 24.5) and in teaching anaesthesia, was an outspoken advocate for patients and anaesthetists, and saw the need for anaesthetists to unite. He suggested in the April 1913 Australian Medical Journal, that a Society of Anaesthetists be established [31], also noting that:

Fig. 24.5

Rupert Hornabrook, self administering ethyl chloride via a nasal inhaler, while submitting himself to an incision in his forearm, followed by suturing. He said pain only occurred during the suturing of the last half inch of the two inch wound, when he became diverted from anesthetic delivery by his conversation with the operator. (Courtesy Geoffrey Kaye Museum of Anaesthetic History, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, Melbourne.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree