WOUNDS TO THE HAND

In the hand, skin is at a premium and must be handled gently and conservatively; toothed forceps should be avoided. The main obstacles to sound healing are haematoma, infection and tension.

- Dead tissue must be excised, but the normal blood supply is good and may maintain flaps that would die elsewhere.

- Cleaning must be thorough. Gentle use of a toothbrush or a scrubbing brush is effective.

- Lacerations over the dorsum of the hand, sustained in a fight, are often inflicted by the opponent’s teeth. They are human bites and must be treated accordingly (→ p. 399).

- Patients with compound fractures should be given systemic antibiotics and referred for specialist care. Osteomyelitis or septic arthritis may not be apparent on a radiograph for the first 10 days after infection.

- All patients with hand wounds must be protected against tetanus. (→ p. 394).

- The median nerve motor supply to the thenar muscles (→ Box 8.6 on p. 120) is very superficial and may be damaged by apparently minor wounds to the radial side of the palm.

- Adhesive, reinforced paper skin closures are not suitable for hand and proximal finger lacerations because they either restrict movement or impair blood supply – and they usually come off!

- Sutures to the palm that are too large (or badly placed adhesive strips) may cause skin overlap and a final, unacceptable, proud wound.

Injection Injuries to the Hand

EpiPen Injection Injuries:

as more patients are issued with self-injecting devices to treat anaphylaxis, accidental injections have become more common. Anti-allergic ‘pens’ (such as EpiPen) contain either 0.15 mg or 0.3 mg adrenaline and so subcutaneous injection is rarely systemically dangerous. However, accidental injection into a digit may cause intense vasoconstriction and even irreversible tissue ischaemia. The affected finger may be pale and white with reduced sensation. Local injection of phentolamine (1.5 mg with 1 mL 2% lidocaine) may be effective in reversing the adrenaline-induced vasoconstriction for up to 13 h after the accidental injection. An opinion from a vascular surgeon may be required. Intravenous infusions of the prostacyclin analogue, iloprost, have also been used in this situation, as has stellate ganglion blockade. Calcium channel blockers and nitrates are ineffective.

High-Pressure Hose Injection Injuries:

high-pressure hoses containing air, water, oil, grease and paint are used in many industries. Injection injuries from these tools can cause delayed but extensive soft-tissue damage. Skin penetration occurs easily (and often relatively painlessly) leaving minimal superficial injury and a normal-looking hand or finger. Initially, the injury may appear trivial but, within 24 h swelling, paraesthesia and loss of function are apparent. Tissue necrosis follows and damage to deeper structures is often widespread. Radiographs may reveal particles or an air track. All of these injuries must be referred for inpatient treatment at the time that they are first seen. Laying open the track and removal of injected particulate matter are often required. Tetanus prophylaxis is essential.

Oil-Based Veterinary Vaccine Injection Injuries:

accidental self-inoculation of oil-based veterinary vaccine fluid leads to intense local pain. The wound may appear trivial but can lead to widespread necrosis. Orthopaedic referral is essential for observation, debridement and decompression, if required.

Crush Injuries of the Hand

Inspection may not be a reliable guide to the extent of crushing. The history can give valuable additional information.

XR

This is almost always indicated.

TX

If the whole hand has been crushed, e.g. between rollers, admission and elevation are necessary even if the initial examination does not reveal extensive injuries.

Less extensive crushing injuries can be treated in the ED by:

- excluding injury to deep structures (radiological and clinical examination)

- providing local anaesthesia

- cleaning thoroughly (scrubbing brush or toothbrush)

- delaying closure for 3–5 days until the oedema has settled.

Amputations of the Fingers

These are common in many industries. Distinguish between crisp sharp injuries where the damage is usually immediately evident and crush or tearing injuries, where the damage is often hidden and complications delayed.

XR

This is necessary to exclude bony damage.

TX

Amputation of the digits proximal to the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint may be suitable for reimplantation (→ p. 394).

Loss of more than the tip of the phalanx requires an orthopaedic opinion. Clean amputations through the terminal phalanx are best treated by primary closure. It may be necessary to trim the bone to allow flaps to be prepared without tension. The volar flap should be the longest, to achieve a dorsal suture line. Crush injuries producing amputation at this level must be left open.

Amputations through the fingertip can be left to close spontaneously. Cleaning must be vigorous and all dead tissue and dirt must be removed. The wound should then be covered with a non-adherent dressing and inspected not more than twice weekly. Antibiotics are not required unless there is bony involvement or infection is evident at the first dressing change. Exposed bone is best treated by referral for trimming.

Partial Avulsion of the Fingertip

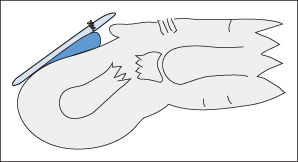

A combination of crushing and flexion of the fingertip (e.g. finger trapped by a door) may partially avulse the proximal end of the nail. There may be an associated crush fracture of the terminal phalanx (→ Figure 9.1). This injury is very common in children.

XR

This should be obtained in all cases.

TX

- Obtain adequate conditions for the repair. General anaesthesia may be necessary but local anaesthesia with a ring block is usually adequate in adults (→ Box 21.2 on p. 392). For sedation of children → p. 352.

- Clean the area thoroughly.

- Restore the normal alignment of the finger. It may sometimes be possible to replace a nail with a firm distal attachment under the proximal skinfold; otherwise remove it. Do not leave the nail in an avulsed position because it will splint the bone and/or finger pulp in the same position.

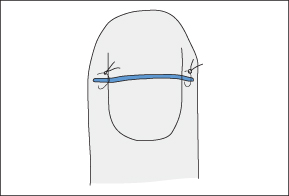

- Maintain the alignment with sutures to the lateral lacerations if needed but do not suture the nail bed (→ Figure 9.2).

- Dress the finger with a non-adherent, antiseptic dressing.

- Provide adequate splintage. A Mallet splint may be slit dorsally for this purpose.

- Arrange follow-up.

The tip of the finger will swell but decompression will occur through the laceration.

Tendon Injuries in the Hand

Injuries to the tendons of the hand are common and often overlooked. Even the smallest wound to the skin may sometimes have allowed sufficient penetration to damage a tendon. Wounds involving glass are particularly sinister in this respect. Loss of function is the only reliable sign. Extensor tendon division is relatively easy to diagnose. For the detection of flexor tendon damage → Box 9.1. Also note the following:

- In the relaxed hand, the fingers tend to be held in increasing flexion from index to little finger. A pointing finger, which is out of line with this trend, suggests a flexor tendon or nerve injury.

- Partial division of a tendon may be overlooked initially but subsequent rupture may occur. Suspicion of a tendon injury warrants referral for exploration.

- The relationship between a tendon and the overlying skin varies with joint position. This means that the damage to a tendon may not be immediately visible through a skin wound. The tendon must therefore be inspected during finger or wrist movements.

Box 9.1 The Detection of Flexor Tendon Injuries

Box 9.1 The Detection of Flexor Tendon InjuriesStay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree