Behaviour is influenced by the interplay between the environment and the psyche, and is modified by drugs. A disturbed patient may have a psychiatric condition, an organic brain lesion, a personality disorder or an emotional upset → Box 19.1 for common acute presentations of mental disturbance. The task of the ED is to:

- identify those patients who need immediate therapy

- support the coping strategies of the patient

- liaise with the appropriate agency for further care.

Box 19.1 The Presentation of Mental Disorders to the Emergency Department

Box 19.1 The Presentation of Mental Disorders to the Emergency Department- Acute psychiatric disturbance (patient with little insight brought to ED by relatives, social workers or the police)

- Psychological symptoms (patient usually self-referred with depression or anxiety)

- Exacerbation of symptoms or loss of control in known psychiatric disease (patient usually has good insight and self-refers; may request admission)

- Personality disorder (self-referred patient with no apparent insight; often manipulative)

- Self-harm

- Alcohol and drug abuse

- Acute emotional upset

Initial Assessment and Management of the Disturbed Patient

Ask About

- Presenting complaints as described by the patient and those accompanying him or her

- The history of the presenting complaints and any accompanying problems

- Current drug therapy and other management and support

- Previous psychiatric history: symptoms, duration, diagnoses, admissions and any treatment received

- Coincidental physical illnesses

- Social circumstances and support (e.g. one in four people with a mental health problem is also in debt).

Look For

- Abnormal appearance or behaviour

- Disorientation or altered conscious level

- Lack of attention or concentration

- Poor memory

- Unusual form or content of speech

- Depressed or elevated mood

- Disordered thought content

- Abnormal beliefs: delusions, misinterpretations and overvalued ideas

- Hallucinations (visual or auditory) and disorders of perception

- Obsessions and compulsions

- The level of insight that the patient has into his or her problems.

These are the main features of the mental state examination. Concise notes may be augmented by verbatim quotes of the patient’s responses to questioning. A brief but comprehensive physical examination is also important to exclude organic causes of disturbance (→ later). This must include:

- temperature

- heart rate

- palpation of the scalp

- blood sugar

- gross neurological signs (walking and talking).

Therapeutic manoeuvres include the following:

- Correction of organic problems (e.g. hypoxia and hypoglycaemia)

- Sedation: oral lorazepam (2 mg) should be tried initially; in extreme cases, intravenous (IV) benzodiazepines (lorazepam or midazolam) may be used. All normal precautions for sedation should be observed, as far as possible. If there is a confirmed history of previous significant antipsychotic exposure, and response, then the use of haloperidol in combination with lorazepam should be considered.

- Referral to a psychiatrist or other agency.

Distinction must be made between:

- responses to adverse life events that may appear logical to the patient, however bizarre to the doctor

- major psychiatric disease that may be distinguished by the history or examination

- other medical conditions that masquerade as psychiatric illness (e.g. head injury, hypoglycaemia, infection, drug disturbance, epilepsy and cerebrovascular disease).

Interaction with the Disturbed Patient

The image portrayed by staff is very important. The patient is extremely vulnerable and sees doctors and nurses as being in a position of power. Occasionally, this will provoke an aggressive response. It is important, therefore, not only that actions cannot be interpreted as threatening but also that staff are never put in a position of vulnerability themselves. Staff should avoid being judgemental and must be sensitive to a patient’s affect. They need to be aware of the potential for manipulative behaviour but must not react to it in a critical manner.

The aim is to support the patient at a time of crisis and to identify appropriate agencies that can provide sustained care. The latter can include the patient’s relatives and friends and the patient’s own resources. Medication and admission – rarely against the patient’s will – may be necessary but physical restraint can be justified only as a prelude to a specific therapy (e.g. holding down a patient while an injection of glucagon or IV glucose is administered).

The patient’s behaviour must be responded to appropriately, e.g. if a patient is rude or abusive this must not be a cue for clever retaliation. Nor must it be ignored. The situation should be briefly summarised and an explanation that such behaviour is unacceptable given. Surprisingly, this sometimes works but, if it does not, lengthy interrogation must be avoided and an early decision made to seek further help from the duty psychiatrist.

Throughout care in the ED it is essential to reassure the patient constantly about the intended course of action and to keep the patient up to date with events.

CONFUSION AND PSYCHOTIC BEHAVIOUR

Acute Confusional States

Delirium has four main features:

Patients at risk include elderly people, and those with dementia, alcohol problems or impaired vision or hearing. A wide range of underlying conditions may be responsible for confusion and disorientation and so a full history and examination is required to establish the cause:

- Hypoxia may present as a toxic confusional state and a psychosis of rapid onset with disorientation, hallucination and delusions. There will be a clouding of consciousness and impairment of recent memory. These sudden alterations in cerebration are very frightening and sufficient to cause aggression in many patients.

- Hypoglycaemia may cause considerable violence and aggression.

- Infection, particularly of the central nervous system (CNS), can also cause an acute confusional state. Elderly patients with any infection (e.g. chest or urinary tract) can present in such a way that the underlying medical condition is completely masked.

- Drug intoxication (→ later and Chapter 15).

- Gross metabolic disturbance, including that found with hepatic and renal failure.

- Organic brain lesions may occasionally present in this way.

- Post-ictal states: there may be aggression and agitation in a similar way to hypoglycaemia.

- Cerebrovascular accidents.

- Myocardial infarction (MI) may present with acute confusion in elderly people.

Investigations:

- Full blood count (FBC), glucose, blood chemistry including calcium, liver function tests (LFTs), thyroid function tests (TFTs) and C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Consider the need for a troponin assay (12 h after the onset of symptoms) to detect an unsuspected MI (→ p. 185)

- Consider the need for serum vitamin B12, folate and ferritin levels

- Chest radiograph (CXR), ECG and mid-stream specimen of urine (MSU)

- Consider the need for a CT scan of the brain.

TX

A safe environment must be maintained and any possible improvement to communication ensured. Family and carers should be involved. Basic observations should be continued and oxygenation and hydration maintained. Retention of urine, constipation, pain and discomfort must be avoided and medications should be reviewed. If possible, catheterisation and sedation should also be avoided. However, it is often impossible to assess fully or manage an agitated patient. In addition, the patient may put him- or herself or others at risk of harm. Adequate sedation makes further therapy possible and may relieve the patent’s distress. Small doses of IV lorazepam (or midazolam) are effective and have a rapid onset of action but careful observation and monitoring are necessary. Where there is a confirmed history of previous significant antipsychotic exposure (and response), haloperidol may be given. Hypoglycaemia is one of the few situations where rapid diagnosis and specific therapy obviate the need for sedation. The use of depressant drugs has been criticised in hypoxaemia because it may decrease respiratory effort. However, in situations of extreme restlessness, judicious sedation decreases oxygen requirements and makes possible the administration of high-concentration oxygen by mask.

Agitation can be greatly reduced if pain is relieved and so analgesia is often helpful. Splintage of injuries and drainage of a full bladder may have a similar effect.

Drug-Induced Psychiatric Syndromes

Prescribed Drugs

Mental disturbance caused by prescribed drugs is particularly common in elderly people but may occur with CNS-depressant drugs, β blockers, digoxin and cimetidine at all ages. Symptoms include fluctuating clouding of consciousness and restlessness with paranoid delusions and visual hallucinations in severe cases. Although usually a result of overdosage, these reactions may sometimes occur because of intolerance to the normal dose or after withdrawal of the drug.

Recreational Drugs

Patients may retain full consciousness but experience paranoid delusions and visual hallucinations after ingestion of cocaine, amphetamines, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psychotropic fungi. Fear and restlessness lead to disruptive and aggressive behaviour. The condition can be distinguished from schizophrenia by the history and often by the extreme nature of the patient’s behaviour.

Psychoses

A psychosis is defined as a significant mental illness that robs the patient of insight and distorts appreciation of the environment. It follows that a psychotic patient cannot be held responsible for his or her actions.

Schizophrenia is now no longer thought to be a single condition. The name embraces a heterogeneous group of clinical syndromes in which hallucinations, delusions and thought disorders are present. The intensity of these symptoms is constantly changing and they may be modified or abolished by drugs. Mood and behaviour are similarly fluctuant.

Patients with both schizophrenia and mania may present acutely to the ED with obvious psychotic behaviour. The distinction between the two conditions can be difficult at times but is not initially important because pharmacological control of symptoms is similar in both conditions.

More commonly, a patient with a known history of schizophrenia comes to the ED with an exacerbation of usually well-controlled symptoms. Loss of therapeutic control may be precipitated by:

- pressure of outside events

- moving area of residence away from long-term support

- omitting depot therapy

- absence of usual support (friends, relatives or care workers).

TX

Psychotic behaviour may necessitate the administration of neuroleptic drugs (e.g. IV or IM [intramuscular] haloperidol 5–10 mg), although oral lorazepam 2 mg and/or oral haloperidol 5 mg may be tried initially. These patients will subsequently require expert care from psychiatrists. In less acute cases, community psychiatric nurses can be a useful source of information and advice.

Medical Conditions in Psychiatric Patients

Up to 50% of psychiatric patients have a medical condition and, in some cases, this may exacerbate psychiatric symptoms. In particular, patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia have an increased incidence of:

- cardiovascular diseases

- endocrine diseases

- infections

- nutritional problems.

There is a corresponding increase in mortality from these conditions and thus medical symptoms in psychiatric patients should always be investigated appropriately.

ALCOHOL-RELATED PROBLEMS

Acute Intoxication with Alcohol

The patient who smells of alcohol may appear merely drunk and disorderly but never assume that this is the only pathology. A coexistent head injury or hypoglycaemia may look identical to the effects of alcohol. Diagnosis of alcohol intoxication must always be made by exclusion – never by neglect.

Alcohol absorption from the gastrointestinal tract will continue for some time after the last ingestion. In comatose patients, blood levels continue to rise for about 2 h after presentation. The patient may appear to be becoming quieter and more cooperative when he or she is in fact becoming more intoxicated. Respiratory depression and inhalation of vomitus can occur quite suddenly.

Alcohol Withdrawal States

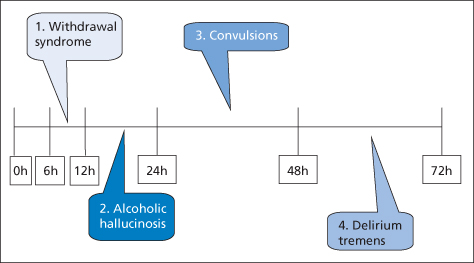

Alcohol withdrawal is not synonymous with delirium tremens. There are in fact several possible presentations that can follow the cessation of drinking in patients who are physically dependent on ethanol.

Acute Withdrawal Syndrome

This occurs within 6–12 h of abstinence and presents as:

- agitation and restlessness (sometimes extreme)

- tremulousness

- sweating

- tachycardia

- anorexia, nausea and retching

- upper abdominal pain (but beware of pancreatitis or ulcer).

TX

Most of the symptoms respond well to IV diazepam. Enormous doses may be needed; the correct dose is apparent by the relief that it affords. Upper abdominal symptoms may be helped by antacids. The patient should be admitted for a reducing dose of oral chlordiazepoxide accompanied by IV fluids and parenteral high-potency vitamins B and C (e.g. Pabrinex two pairs of ampoules intravenously three times daily for 2–5 days). Oral vitamin therapy should be prescribed concurrently: vitamin B compound strong two tablets three times daily and thiamine 50 mg four times daily. The thiamine can be discontinued once the chlordiazepoxide detoxification regimen is complete but the high-dose oral vitamin B should be continued indefinitely.

Generalised Convulsions

Fits may be recurrent and require short-term treatment as well as a long-term management strategy. Concurrent head injury must be excluded as a cause. Patients with withdrawal seizures should be prescribed carbamazepine 200 mg three times daily throughout the period of withdrawal. The drug can be reduced and stopped over 3–5 days when the detoxification is complete. If the patient is already taking an anticonvulsant drug such as phenytoin, there is no need to prescribe additional carbamazepine.

Acute Alcohol Hallucinosis

Around 10% of people withdrawing from alcohol will suffer from auditory and visual hallucinations while fully conscious and situationally aware. The onset is within 12–24 h of abstinence and resolution occurs within 24–48 h. The hallucinations are vivid and voices may be described such as those of family or friends, often threatening or degrading in manner. This is a distinct condition, separate from other withdrawal states, which should be discussed with a psychiatrist. Intravenous haloperidol (5–10 mg) may be helpful.

Delirium Tremens

This occurs after 24–72 h of abstinence and is recognised by:

- agitation and restlessness

- tremulousness

- fever and tachycardia

- delirium (acute confusional psychosis with bizarre visual hallucinations often concerning animals or insects)

- fits.

TX

Delirium tremens has a high mortality rate (up to 5%), so intensive monitoring and observation are mandatory. The patient will need adequate sedation and supportive therapy.

Alcoholism

Alcoholism is a descriptive rather than a diagnostic term. The person with alcohol problems (alcoholic) continues to drink despite obvious harm to self and family. Addiction is a more specific description indicating tolerance, craving and withdrawal symptoms attributable to the drug. Every alcohol addict is an alcoholic but not every alcoholic is an addict. Many simply binge drink, wreak havoc with their lives for a brief period and then return to ‘normality’. This, of course, is very disruptive to home and family. The following are the main features of true dependency on alcohol (addiction):

- Difficulty or failure to carry out daily life if there is an absence of alcohol

- Same daily pattern of drinking

- Increased tolerance to alcohol

- Compulsion for alcohol

- Priority in life is to maintain alcohol intake

- Symptoms of withdrawal (→ p. 361).

Signs of chronic alcohol abuse include:

- poor nutritional status

- raised γ-glutamyl transpeptidase

- macrocytosis in the absence of folate or vitamin B12 deficiency

- multiple rib fractures at various stages of healing on CXR (pulmonary tuberculosis [TB] may also be present)

- atrial fibrillation.

A slow downward spiral often leads to the loss of driving licence, job and home, and then to residence in a hostel or on the streets.

Requests for detoxification are often made to ED staff. Unfortunately, there are very few acute facilities available for people requiring this sort of help and those that do exist require a completely sober individual. This is difficult to achieve because sobriety is usually accompanied by any one of the withdrawal states detailed above. The best policy is probably to advise the patient (ideally in the presence of carers) to continue drinking alcohol in sufficient quantities to hold off the worst of the withdrawal symptoms until attendance at a specialist clinic can be arranged. However, timely facilities for such help are in short supply in the UK.