For the surgeon, examination of the cardiovascular system (observing or measuring the parameters listed in

Table 3.7) is used primarily to assess total body and regional perfusion. When perfusion is inadequate, then physical exam can provide an assessment of the likely etiology.

Total Body Perfusion

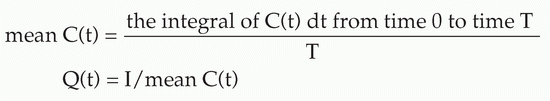

Measurement of the vital signs (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pulse, respiration, temperature) is the first step of the physical examination. As evident in the calculations in

Table 3.2, blood pressure is determined by both cardiac output (flow) and resistance. Frequently, a decrease in blood pressure indicates a decrease in cardiac output (hypoperfusion), especially when the neuroendocrine response to decreased flow causes increased vascular resistance. However, blood pressure may be in the normal range or elevated in the face of hypoperfusion, with conditions such as congestive heart failure (CHF), hypothermia, and in patients with underlying hypertension with a baseline pressure above the normal range. In addition, hypotension may be present during normal or augmented perfusion, such as that occuring in severe inflammation or spinal cord injury, when the reason for a lower pressure is a lower resistance rather than lower flow. Orthostatic hypotension (>20 mm Hg drop in systolic, >10 mm Hg drop in diastolic pressure) is more specific for intravascular volume depletion, but often difficult to obtain in surgical critical care settings.

Tachycardia is a more sensitive indicator of hypoperfusion and orthostatic stress but is less specific and can be a result of various other causes (i.e., anxiety, pain, temperature elevation, delirium). Respiratory rate and depth can be increased as a response to the acidosis of decreased oxygen delivery, but is also subject to other stimuli. Core temperature can be increased in hyperdynamic circulatory states and decreased with severe hypoperfusion (see below).

With mild-to-moderate hypoperfusion, patients often become restless and agitated, pulling at restraints, intravenous lines, and nasogastric tubes. Severe hypoperfusion can result in obtundation and coma.

Most commonly, hypoperfusion stimulates a neuroendocrine response that results in peripheral vasoconstriction and, consequently, pale to cyanotic and cool to cold extremities. Skin covering the patella is particularly sensitive to hypoperfusion and vasoconstriction here, resulting in “purple knee caps” that may be an early clinical sign of hypoperfusion. Skin temperature (cool vs. warm) may be particularly useful for identifying patients with a hyperdynamic circulation (warm extremities) (

16).

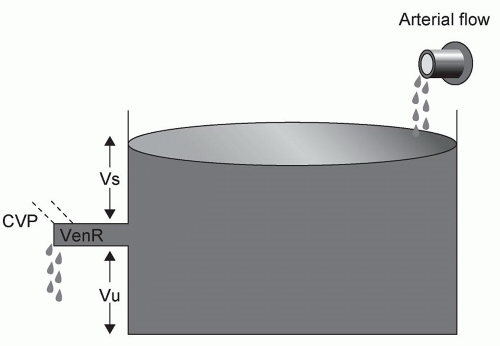

Distended neck veins are consistent with impairment of cardiac function, but not always with CHF or cardiogenic shock (

17). CVP elevation and neck vein distention may be secondary

to a force exerted outside the lumen of the right atrium (tension pneumothorax, pericardial tamponade, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), prolonged expiration in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)].

Examination of the heart focuses on the quality of heart sounds (diminished sounds may represent pericardial fluid or shift of the mediastinum) and the presence or absence of murmurs and/or a gallop. Distinguishing an S3 gallop from an S4 may be difficult, especially with tachycardia. The distinction is important, however, since an S4 is common in patients aged 50 years and above and an S3 is quite specific but not very sensitive for a failing left ventricle (

17,

18).

Urine output at least 0.5 cm3/kg/hr is usually considered an indication of adequate total body perfusion. Unfortunately, as described in the section on “Confounding Variables,” even this clinical tool must be evaluated with caution. Importantly, examination of the lungs and extremities for evidence of edema is not specific for cardiac dysfunction. As will be emphasized later, in surgical critical illness total body salt and water excess is commonly associated with, at best, a normal, but still too frequently, a decreased intravascular volume. Under these circumstances, relying on the lung or the periphery to draw conclusions about cardiac filling and function can be dangerously misleading.

Regional Perfusion

Physical examination evidence of regional hypoperfusion is limited primarily to the extremities. A painful, pale, pulseless, paralyzed, and cold extremity with paresthesia is diagnostic of acute arterial insufficiency. Chronic arterial insufficiency demonstrates loss of pulse, hair loss, dependent rubor, and sometimes loss of muscle mass. Acute venous obstruction, particularly in the iliofemoral region, may also cause decreased extremity perfusion. The lower extremity may be edematous and white (phlegmasia alba dolens) with little arterial compromise, or edematous and blue (phlegmasia cerulea dolens) with increased muscular pressure sufficient to diminish arterial circulation and cause tissue necrosis, often resulting in skin with fluid-filled bullae.

Physical examination alone is rarely sufficient to evaluate precisely other types of regional hypoperfusion (cerebral, gastrointestinal), but can contribute greatly to the overall clinical evaluation. For instance, evidence of sudden neurologic deficit consistent with middle cerebral artery occlusion or an unremarkable abdominal exam coexistent with severe abdominal pain may lead to the diagnosis of cerebral and intestinal infarction, respectively.