Syncope

Shamai A. Grossman and Christopher M. Fischer

Syncope is a sudden and transient loss of consciousness that is associated with a loss of postural tone and that resolves spontaneously and completely without intervention. In the United States, syncope accounts for an estimated 740,000 emergency department (ED) visits annually. This represents approximately 0.8% of all ED visits nationally. Nationally, approximately one-third of all ED patients with syncope are admitted, representing approximately 2% of all admissions from the ED (1). Although the pathophysiology of syncope is related to a transient decrease in cerebral blood flow, the etiologies of syncope are myriad and range from the benign to the life threatening. This range of severity contributes to the problematic nature of the ED evaluation of the patient with syncope. In addition, the lack of accurate historical information and the fact that patients are usually asymptomatic when evaluated combine to fuel diagnostic uncertainty and often leads to extensive testing in the ED. Annual healthcare costs associated with syncope in the United States exceed $3.8 billion, an amount comparable to the total annual hospital costs of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and HIV (2). The emergency physician is faced with the challenge of identifying those patients with potentially life-threatening processes (e.g., dysrhythmias, pulmonary embolism, subarachnoid hemorrhage, acute coronary syndromes), other patients who may require hospitalization and intervention (e.g., patients with bradycardia or medication-induced orthostatic hypotension), and those patients who have a more benign cause of syncope. When the initial ED evaluation of a patient presenting with syncope does not reveal a clear etiology, the emergency physician must determine which patients require further diagnostic evaluation and monitoring and which patients can be safely discharged home.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A detailed history and thorough physical examination remain the cornerstone of accurate diagnosis of syncope in the ED. However, even with a thorough initial evaluation, a definitive etiology of syncope is often difficult to establish. Historical information should focus on the events and symptoms before, during, and after the episode, as well as on the past medical and medication histories. Certain elements of the history of the episode may direct the emergency physician toward possible causes of syncope. Tongue biting, the presence of a postictal period, or urinary incontinence may suggest that seizure rather than syncope caused the patient’s symptoms (3). Syncope occurring while the patient is seated or reclining is more likely to have a cardiac etiology (4), whereas syncope that occurs after standing may suggest orthostatic hypotension (5). Exertional syncope, especially in younger patients, raises concerns about structural defects producing fixed cardiac output, such as hypertensive cardiomyopathy. Absent or brief preceding symptoms, including palpitations and dizziness, may be associated with dysrhythmias, whereas longer prodromes, often including nausea or vomiting, more commonly accompany neurally mediated syncope, also known as vasovagal syncope or neurocardiogenic syncope. Obvious precipitating events or stresses may lead one to consider the diagnosis of neurally mediated syncope, but caution should be exercised, because these prodromal symptoms are often subjective and agreement on the presence of “vagal” symptoms and the eventual diagnosis is inconsistent among physicians (6).

Corroborating history from witnesses and prehospital care providers is a vital source of information and should be obtained whenever possible. These individuals are often able to provide information that the patient is unable to provide, including estimation of duration of loss of consciousness, evidence of seizure activity, and duration of confusion or lethargy after the episode.

A detailed medication history should also be obtained. Vasoactive medications, including antihypertensive agents, antianginal medications, and medications used to treat erectile dysfunction, may lead to syncope because of their vasodilatory effects. Medication interactions may prolong the QT interval and lead to potentially life-threatening dysrhythmias. Elderly patients in particular are more susceptible to medication effects that may cause syncope, and close attention should be directed to potential medication interactions in these individuals.

The role of patient age in the diagnostic evaluation of syncope is not clearly defined. Some studies have demonstrated the importance of age as a predictor of poorer outcome in patients with syncope of any cause, but other studies suggest that age is not an independent predictor of adverse outcome in syncope (7,8). Clearly, there is no single age that places a patient at higher risk for serious outcomes. It should be recognized that while syncope in younger patients is often caused by a single pathologic process, in older patients it is often multifactorial. Older patients are especially prone to syncope as a consequence of a combination of age-related alterations in the cardiovascular system, multiple comorbidities, and the use of numerous medications (9).

The medical history should focus on predisposing conditions that place patients with syncope at a higher risk for serious outcomes. Of particular note, attention should be paid to any history of cardiovascular disease. A history of coronary artery disease places patients at greater risk (10), and a history of poor left ventricular function or heart failure is consistently predictive of a greater risk of sudden death (6,11). Syncope in the patient with heart failure is a poor prognostic sign, and patients with impaired left ventricular function may be at higher risk for sudden death, even when they are diagnosed with a noncardiac etiology for their syncope (12).

Physical examination should focus on vital signs, a careful cardiovascular examination, and a detailed neurologic evaluation. Vital sign abnormalities, including persistent tachycardia or hypotension, are of concern and must prompt a search for an underlying cause. Orthostatic hypotension (usually defined as a decrease in systolic blood pressure with standing of 20 mm Hg or greater) may identify some patients with syncope related to volume depletion, autonomic insufficiency, or medications. However, it is a common finding in up to 40% of asymptomatic patients older than 70 years and 23% of patients younger than 60 (13). The diagnosis of orthostatic hypotension as a cause of syncope should be approached with caution and should probably represent a diagnosis of exclusion in low-risk patients, because many high-risk patients also have orthostasis.

Physical examination findings of congestive heart failure, including elevated jugular venous pressure, dependent edema, and rales are concerning predictors of sudden death after syncope. Murmurs that may be indicative of valvular heart disease or outflow obstruction should prompt further evaluation for structural heart disease, usually with echocardiography.

Abdominal pain or tenderness associated with syncope must be investigated, with close attention to possible intra-abdominal pathology or hemorrhage. Rectal examination, with testing of the stool for blood, is recommended if gastrointestinal hemorrhage is suspected.

A detailed neurologic examination should be performed. Because syncope is associated with complete and spontaneous return to normal neurologic function, focal neurologic deficits should raise concerns for other diagnoses including stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA), and prompt further investigation, including brain imaging, Although objective evidence of seizure activity is difficult to ascertain, lateral tongue biting and signs of urinary incontinence suggest seizure, although the absence of either of these does not exclude the diagnosis. Some studies have suggested that anterior tongue biting is more commonly associated with syncope, whereas lateral tongue biting is more suggestive of seizure (14). Seizures classically present with a prodromal aura or “warning” symptoms and are typically followed by a postictal period in which the patient is often lethargic, agitated, or confused, with a gradual return to full consciousness. More than 5 minutes of loss of consciousness and rhythmic movements can be seen in both seizures and syncope but are far more common in patients who have had a seizure.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

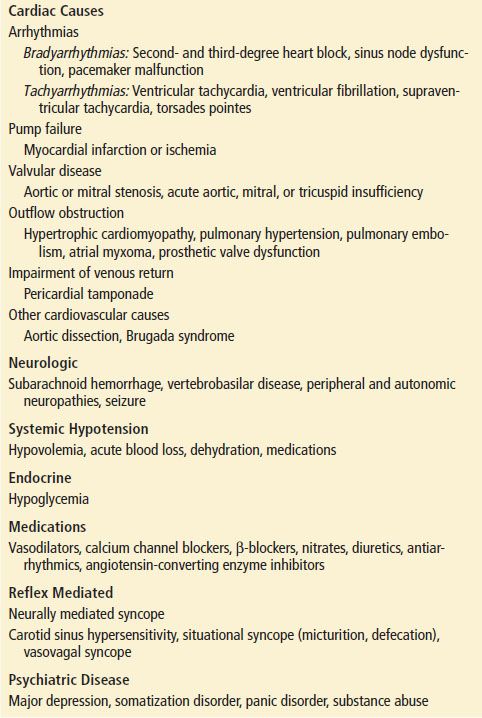

The transient reduction in cerebral blood flow that is responsible for most causes of syncope results in temporary underperfusion of both cerebral hemispheres simultaneously or sections of the brainstem thought to be responsible for the conscious state (the reticular activating system). Transient reversible underperfusion in the brain may also be caused by a sudden increase in intracranial pressure from trauma or other brain injuries that limit cerebral blood flow (Table 9.1).

TABLE 9.1

Differential Diagnosis of Syncope (From Higher to Lower Risk)