78 Supraventricular Arrhythmias

Classification and Epidemiology

Classification and Epidemiology

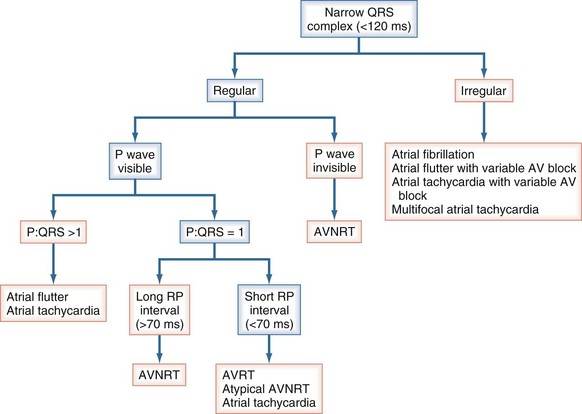

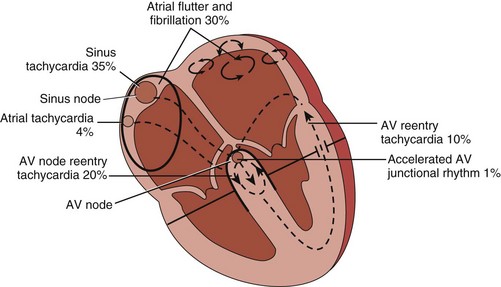

Supraventricular arrhythmias include rhythms arising from the sinus node and the adjacent atrial tissue (inappropriate sinus tachycardia, sinoatrial reentry tachycardia), both the right and left atria (atrial tachycardia, flutter, and fibrillation), the atrioventricular (AV) node (AV nodal reentry tachycardia, accelerated ectopic junctional rhythm), and the AV node, with involvement of an accessory pathway or multiple pathways (AV reentry tachycardia) (Figure 78-1).

Figure 78-1 Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias encountered in the emergency setting. AV, atrioventricular.

Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry Tachycardia and Atrioventricular Reentry Tachycardia

AV nodal reentry tachycardia and AV reentry tachycardia are usually referred to as paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias and are often seen in young patients with little or no structural heart disease, although a congenital heart abnormality giving rise to increased atrial pressure and dilatation (e.g., Ebstein’s anomaly, atrial septal defect, Fallot’s tetralogy) can coexist in a small percentage of patients with these arrhythmias.1 The first presentation is common between age 12 and 30 years, and the prevalence is approximately 2.5 per 1000. Women are twice as likely as men to present with AV nodal reentry tachycardia.

Atrial Flutter and Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is the most common supraventricular arrhythmia, affecting 1% to 2% of the general population, especially the elderly. It is usually associated with cardiovascular pathologies, among which hypertension and congestive heart failure prevail.2 About a third of patients, however, present with no underlying heart disease and are considered to have “lone” atrial fibrillation. The epidemiology of isolated atrial flutter is largely unknown and is believed to be in the range of 0.037% to 0.88% per 1000 person-years, but at least half these patients also have atrial fibrillation as a coexistent arrhythmia.

Electrocardiography

Electrocardiography

Narrow-Complex Tachycardias

The typical ECG feature is narrow QRS complexes less than 120 msec. In this case, the tachycardia is almost always supraventricular, and the differential diagnosis relates to its mechanism (Figure 78-2).

Wide-Complex Tachycardias

The differential diagnostic features of wide-complex tachycardias favoring a supraventricular origin of the arrhythmia include, but are not limited to, preexistent bundle branch block; rate-dependent aberrancy; antidromic AV reentry tachycardia, when an accessory pathway conducts and excites the ventricles antegradely; and prominent electrolyte abnormalities (e.g., hypokalemia) or heart muscle disease (cardiomyopathy), all of which may result in QRS widening (Figure 78-3). If the diagnosis of supraventricular tachycardia cannot be proved, the patient should be treated as if ventricular tachycardia is present. Immediate direct-current (DC) cardioversion is the treatment for any hemodynamically unstable tachycardia.

Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry Tachycardia

Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry Tachycardia

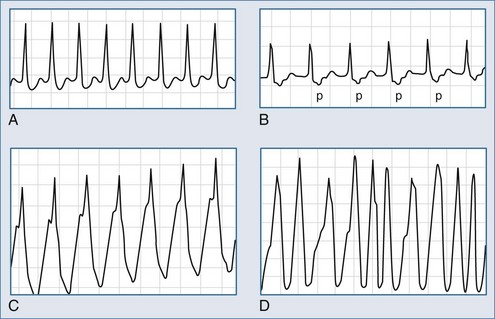

Electrocardiographic Presentation

In sinus rhythm, the ECG is usually normal unless other unrelated abnormalities are present. During AV nodal reentry tachycardia, the rhythm is regular, with narrow QRS complexes and a rate of 140 to 250 beats per minute. The atria are activated retrogradely, producing the inverted P waves in leads II, III, and aVF. Because atrial and ventricular depolarization occurs simultaneously, the P waves are often obscured by the QRS complexes and cannot be detected on the surface ECG (Figure 78-4, A). However, in about a third of cases of slow-fast AV nodal reentry tachycardia, a terminal positive deflection in lead aVR or V1 (or both), imitating right bundle branch block or pseudo-S waves in the inferiorly oriented leads, may be present, reflecting retrograde activation of the atria. Tachycardia using these pathways in reverse (“fast-slow,” or long RP, tachycardia) is less common (5%-10% of cases).

Atrioventricular Reentry Tachycardia

Atrioventricular Reentry Tachycardia

Mechanism and Electrocardiographic Presentation

The reentry circuit of orthodromic AV reentry tachycardia involves the AV node and an accessory pathway, with the impulses conducting from the atria to the ventricles over the AV node and traveling in the reverse direction through the accessory pathway (see Figure 78-4, B). In antidromic AV reentry tachycardia, the reentrant impulses conduct antegradely from the atria to the ventricles via an accessory pathway and retrogradely via the AV node or a second accessory pathway (see Figure 78-4, C). Antidromic AV reentry tachycardia is uncommon (<10% of cases). Atrial fibrillation is usually encountered in patients with antegradely conducting pathways (see Figure 78-4, D).

Acute Management

In an emergency, distinguishing between AV nodal reentry tachycardia and AV reentry tachycardia may be difficult, but it is usually not critical, because both tachycardias respond to the same treatment. If the patient is hemodynamically stable, vagal maneuvers including carotid sinus massage, Valsalva maneuver, and facial immersion in cold water (diving reflex) can terminate tachycardia in about 50% of patients (Box 78-1).3,4 Commercially available gel packs can be used as cold compresses instead of facial immersion, but the most important element is wet nostrils and breath-holding.

Box 78-1

Vagal Maneuvers to Terminate Tachycardia

Carotid Sinus Massage

Valsalva Maneuver

Pharmacologic Termination

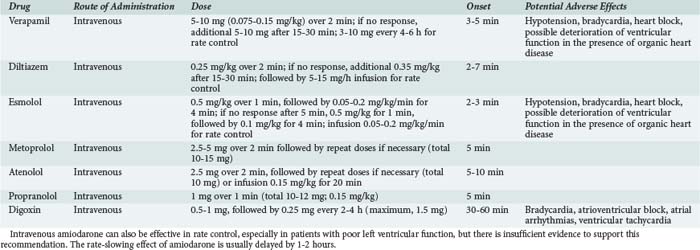

AV blocking agents such as adenosine, verapamil, diltiazem, and beta-blockers are effective in terminating both AV nodal reentry and AV reentry tachycardia (Table 78-1).1

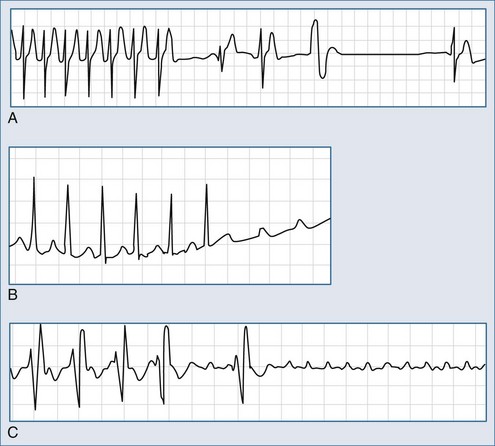

Adenosine

Intravenous (IV) adenosine is effective in diagnosing, rate slowing, and often terminating narrow-complex tachycardias.5 Adenosine usually terminates AV nodal reentry tachycardia and AV reentry tachycardia but rarely interrupts the atrial flutter circuit and does not suppress automatic atrial tachycardia; it can, however, produce high-degree AV block during which the tachycardia persists (Figure 78-5). It has no effect on most ventricular tachycardias. Adenosine is advantageous compared with verapamil because of its rapid onset and the absence of a negative inotropic effect in patients with poor left ventricular function and those with significant hypotension.

Adenosine is administered as a very rapid 3- to 6-mg IV bolus; if this is ineffective, another 6- to 12-mg bolus can be given 2 to 5 minutes later. Adenosine is metabolized very quickly, with an effective half-life of 10 seconds. Adverse effects including dyspnea, facial flushing, and chest tightness are therefore short-lived, but in about 12% of patients, adenosine may shorten the atrial effective refractory period and provoke atrial flutter or fibrillation or accelerate conduction over the accessory pathway and produce a rapid ventricular response. In a proportion of patients, ventricular premature beats and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia may occur after the successful termination of supraventricular tachycardia.6 Some individuals, particularly heart transplant recipients, are unusually sensitive to adenosine and require a lower dose (1 mg).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree