Sudden Cardiac Death: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Future Directions

Steven H. Mitchell

Graham Nichol

Cardiac arrest is the cessation of cardiac mechanical activity as confirmed by the absence of signs of circulation.1 SCD describes the unexpected natural death from a cardiac cause within a short time period, generally 1 hour from the onset of symptoms, in a person without any prior condition that would appear fatal.2

The incidence of ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia (VF/VT) cardiac arrest is decreasing, but there is little improvement in survival from cardiac arrest over time.

The median reported survival to discharge from cardiac arrest is only 6.4%.

Most community-based cardiac arrests occur in a low-risk subset of the population.

Only broad implementation and ongoing maintenance of adequately funded emergency medical services (EMS)—staffed by highly trained, experienced providers—can have a meaningful impact on death due to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Definition of Cardiac Arrest

The terms “cardiac arrest” and “sudden cardiac death” (SCD) are used interchangeably to refer to similar clinical conditions. SCD describes the unexpected natural death from a cardiac cause within a short time period, generally 1 hour from the onset of symptoms, in a person without any prior condition that would appear fatal.2 An international consensus workshop classified cardiac arrest as the “cessation of cardiac mechanical activity, as confirmed by the absence of signs of circulation.”1

This definition emphasizes that cardiac arrest is a clinical syndrome that involves the sudden (usually <1 hour from onset of first symptoms until death) loss of detectable pulse or cessation of spontaneous breathing. If an EMS provider or physician did not witness the event, whether a primary cardiac arrest has occurred may be uncertain, especially if spontaneous circulation has returned. The World Health Organization proposed an alternate definition acknowledging that many cardiac arrests are not witnessed: for those patients without an identifiable noncardiac etiology, cardiac arrest includes death within 1 hour of symptom onset for witnessed events or within 24 hours of having been observed alive and symptom-free for unwitnessed events.3

Such definitions have several limitations despite their widespread use. First, “presumed cardiac etiology” is frequently used as an inclusion criterion, but it can accurately be determined only by conducting a postmortem examination. Since it is impractical to perform an autopsy on every fatal arrest, classification must rely on the limited information that is available to emergency providers in the out-of-hospital setting or physicians in the emergency department (ED).4 It is frequently difficult for emergency providers—when they are trying to provide acute resuscitation in the field—to ascertain whether and how long the patient had symptoms beforehand. In the absence of precise definitions, use of the etiology of arrest as an inclusion criterion can create bias. Therefore, episodes should be included in epidemiologic studies regardless of their etiology.

Since the likelihood of underlying disease is uncertain, many studies presume that an arrest is of cardiac origin unless there is another obvious cause. Specifically, unless the episode is known or likely to have been caused by trauma, submersion, drug overdose, asphyxia, exsanguinations, or any other noncardiac cause as determined by the rescuers, SCD is assumed to have occurred.1

Second, many epidemiologic studies of cardiac arrest use EMS as the sampling frame; therefore, unwitnessed deaths that did not result in a call for aid

are difficult to ascertain and not included. The exclusion of such patients from a study would underestimate episode incidence and overestimate survival compared to a study that included them.

are difficult to ascertain and not included. The exclusion of such patients from a study would underestimate episode incidence and overestimate survival compared to a study that included them.

Third, there is geographic variation in the frequency of “do not attempt resuscitation” declarations by individuals and family members and whether EMS providers can choose to not initiate or cease efforts in the field. The inclusion or exclusion of such patients in different epidemiologic studies makes it difficult to compare the incidence and outcome of cardiac arrest in different jurisdictions.

Reasonable alternative definitions that address these limitations are cardiac arrest without any reference to duration of symptoms and EMS-treated cardiac arrest. The latter would apply to any person evaluated by organized EMS personnel who (1) receives attempts at external defibrillation (from lay responders or emergency personnel) or receives chest compressions by organized EMS personnel or (2) is pulseless but does not receive attempts to defibrillate or provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) from EMS personnel. This would include those with “do not attempt resuscitation” directives, a history of terminal illness or intractable disease, or a request from the patient’s family to not treat.

Cardiac arrest generally occurs in persons with known or previously unrecognized ischemic heart disease.5,6 Other causes of cardiac arrest include nonischemic heart disease (especially arrhythmic, including ventricular fibrillation, Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, long-QT syndrome, Brugada’s syndrome, short-coupled torsade de pointes, and catecholamine-induced polymorphic ventricular tachyarrhythmia), pulmonary diseases including embolus, cerebral nervous system disease, vascular catastrophes including ruptured aneurysms, as well as drugs and poisons. Patients without identifiable abnormalities are categorized as idiopathic. Traumatic sudden death is usually considered separately from unexpected cardiac death because the treatment and prognosis of traumatic and nontraumatic arrest differ so much from each other.

Epidemiology of Cardiac Arrest

Much of what we understand today about the basic pathophysiology of cardiac arrest has been gained through observational rather than randomized studies of patients at risk for or in a state of cardiac arrest. This is only natural, since cardiac arrest is a relatively unpredictable event that usually occurs out of hospital and is initially treated by EMS providers; the patient is then transported to hospital for further triage and treatment in the ED. The epidemiologic study of cardiac arrest not only provides information about risk factors for the onset of arrest and the current status of treatment of the condition but also suggests how to improve treatment and directs physicians toward future studies of resuscitation.

Risk Factors for Sudden Cardiac Death

Clinical (CAD)

Cellular–genetic (long-QT syndrome)

Environmental (stress)

Behavioral (smoking)

Educational and social

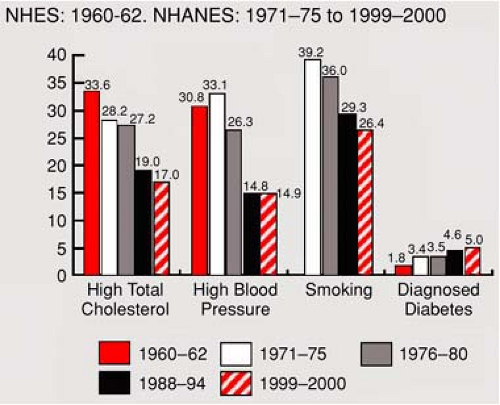

In broad terms, epidemiologic data are used to identify risk factors for cardiac arrest. These include cellular factors (e.g., gene mutations that predispose to arrhythmias); environmental, social, educational, behavioral factors (e.g., activity level, smoking); clinical factors (e.g., atherosclerosis, reduced ventricular function, diabetes); and health-system risk factors that predispose individuals to cardiac arrest or particular outcomes after the onset of arrest. By identifying risk factors that are amenable to modification, such as diet or smoking, physicians have attempted to improve survival through prevention, including use of pharmaceutical agents (e.g., beta-blockers) which can reduce an individual’s risk of cardiac arrest (Fig. 2-1).

By identifying favorable interventional factors for survival, such as early CPR, physicians have improved the acute treatment of sudden death. The ability to identify individuals who have survived cardiac arrest enables physicians to use implantable cardioverter-defibrillators to reduce the risk of further cardiac arrest.8 Implantation of these devices shortly after an acute cardiovascular event is deleterious,9 but noninvasive alternatives exist for high-risk individuals.10

By identifying favorable interventional factors for survival, such as early CPR, physicians have improved the acute treatment of sudden death. The ability to identify individuals who have survived cardiac arrest enables physicians to use implantable cardioverter-defibrillators to reduce the risk of further cardiac arrest.8 Implantation of these devices shortly after an acute cardiovascular event is deleterious,9 but noninvasive alternatives exist for high-risk individuals.10

During the early twentieth century, the incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD) in the United States and other high-income countries increased dramatically. In the 1940s, cardiovascular disease (CVD) became the leading cause of death, overtaking deaths caused by infectious agents. In the early twenty-first century, CVD has become a ubiquitous cause of morbidity in most countries.11 This epidemiologic transition reflects increased longevity in low- and middle-income countries and thereby increased exposure to cardiovascular risk factors. It also reflects adverse lifestyle changes, including increased inactivity, obesity, tobacco use, and consumption of saturated fats.

There has been a steady decline in morbidity and mortality from most CVD in high-income countries over the last 30 years.12,13,14 Much of this reduction has been attributed to risk-factor modification.15 Globally, CVD contributes 30.9% of global mortality and 10.3% of the global burden of disease.16,17,18 It is responsible for more deaths than any other disease in industrialized countries and three-quarters of mortality due to noncommunicable diseases in developing countries. Eighty percent of deaths due to CVD occur in low- and middle-income countries.

In the United States, CVD is the leading cause of death among individuals aged above 65 years of age; it is the second leading cause of death among individuals 0 to 14 years and 25 to 64 years of age and the fourth leading cause of death among individuals 15 to 24 years of age (http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3000963, accessed April 24, 2008). CVD is estimated to have cost $448.5 billion in the United States in 2008 (http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov.easyaccess1.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/about/factbook/chapter4.htm#4_7, accessed April 24, 2008).

Incidence

Incidence is the occurrence rate per year for a disease within a population at risk. It is usually calculated by taking a ratio of the number of persons developing a disease each year divided by the population at risk. This “simple” measurement becomes quite complicated when applied to cardiac arrest because of the effect of age on the incidence. Many cardiac arrest studies reported incidence as the number of cardiac arrests per year divided by the population within the region. If we use Seattle—with a census population of 460,000 aged 20 years or older—as an example, there were 372 cardiac arrests within the metropolitan area during the year 2000, which is an incidence of 372/460,000/yr or 0.81 cardiac arrests/1,000/yr. Focusing on the adult population like this is convenient, yet underestimates the total number of arrests slightly, but not the incidence, since cardiac arrest is uncommon in the pediatric population.

A separate but related issue is that incidence rates are usually based on the census population of the catchment area of the EMS agency, even though the number of individuals fluctuates by time of day and day of week. A city that has a large population ingress during the working week may appear, falsely, to have an elevated rate of unexpected cardiac death.

If large, unaccountable differences in incidence are present, there are important public health questions that require investigation and may prove critical for efforts to improve survival. Likewise, this information may be useful for comparing survival statistics from different communities. Therefore, incidence should be routinely reported in cardiac arrest studies.

The true incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is unknown. About half of coronary heart deaths are sudden.19 Since there were 7.2 million coronary heart deaths worldwide in 2002 (http://www3.who.int.easyaccess1.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/whosis/), this implies that there were 3.6 million unexpected cardiac deaths. About two-thirds of these occur without prior recognition of cardiac disease. About 60% are treated by EMS.20 Although the proportion of those treated by EMS is likely less in those countries that have limited access to emergency services, this implies that as many as 2.2 million cardiac arrests are treated by EMS worldwide annually.

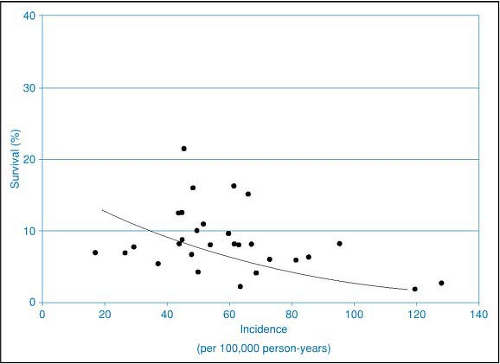

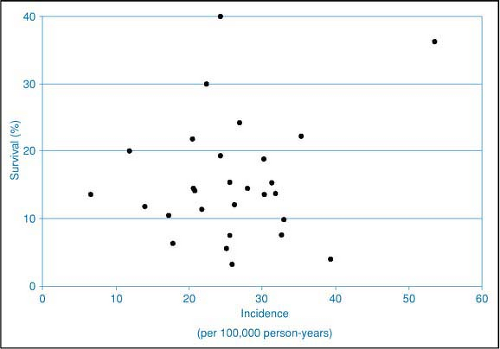

The reported incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States is 1.9/1,000 person-years among those aged 50 to 79 years. Since the U.S. population aged 50 to 79 is estimated to be 78 million (http://www.census.gov/), this implies 148,000 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. The reported incidence of EMS-treated cardiac arrest is 36/100,000 to 81/100,000 total population (Fig. 2-2).20,21 Since the total U.S. population is 301 million (http://www.census.gov/), this implies 107,000 to 240,000 treated arrests occur in the United States annually. Of these, 20% to 38% have ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia (VF/VT) as the first recorded rhythm (Fig. 2-3).21,22 This implies 21,000 to 91,000 treated VF arrests annually. Although the incidence of VF and cardiac arrest with any first initial rhythm is decreasing over time,21 there has been little improvement in survival from cardiac arrest.23,24

The reported incidence of unexpected cardiac arrest in Europe is 1/1000 population.25 Since the European Union’s population is 492,646,492 (http://www.populationdata.net/, accessed April 24, 2008), this implies that 490,000 out-of-hospital arrests occur annually in European Union countries.

Cardiac Arrest in Children

Cardiac arrest in children merits special consideration in the field of acute resuscitation because its characteristics differ from those of out-of-hospital adult episodes. SCD accounts for 19% of sudden deaths in children aged 1 to 13 and 30% in those aged between 14 and 21 years.26 The reported incidence of out-of-hospital pediatric cardiac arrest is 2.6 to 19.7 annual cases per 100,000.27 These are usually due to trauma, sudden infant death syndrome, respiratory causes, or submersion,28 but VF is still commonly

observed.29 The reported average survival to discharge is 6.7%. Children with submersion or traumatic injury have a poorer prognosis.

observed.29 The reported average survival to discharge is 6.7%. Children with submersion or traumatic injury have a poorer prognosis.

Cardiac Arrest in Hospital

Cardiac arrest in hospital also merits special consideration because of its unique characteristics. A large multicenter cohort study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest events excluded events that occurred out of hospital so as to avoid double counting.30 For adults, the reported incidence of unexpected cardiac death in hospital was 0.17 ± 0.09 per bed per year. The commonest causes of these events were arrhythmia, respiratory distress, hypotension, or myocardial infarction (MI). The average survival to discharge was 17%.

Epidemiology of High-Risk Subgroups

The patients at highest risk for cardiac arrest account for only a small portion of arrests in the community.31 The largest number of cardiac arrests in the community occur in the low-risk general public simply because there are so many more of these individuals in that group than in the high-risk subgroups.

Coronary Artery Disease and Acute Coronary Syndromes

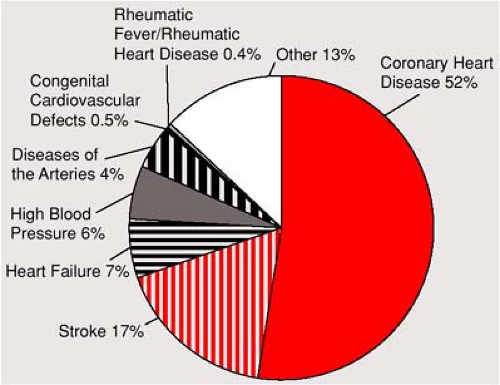

Nonetheless certain populations are at increased risk for cardiac arrest. The rates of cardiac arrest parallel the prevalence of risk factors for CAD (Fig. 2-4). Known CAD or a previous episode of sudden death remains the greatest risk factor for sudden death.

Patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) that include MI are at high risk of mortality (i.e., >5%) within 30 days of presentation, regardless of whether ST-segment elevation is present or absent.32 The risk of death remains elevated for at least 6 months in patients with ACS33 and for at least a year in patients with MI.34 Patients with ventricular dysfunction are at higher risk than those without.35 At least one-half of these deaths are suspected to have an arrhythmic mechanism.36

Figure 2-4 • Percentage breakdown of deaths from cardiovascular diseases, United States, 2004. (From CDC/NCHS.) |

Several noninvasive diagnostic tests can identify patients who are at high risk of cardiac arrest, but they have low sensitivity and specificity37 and are generally available only in tertiary care centers. An estimated 1,413,000 people will be discharged with a diagnosis of ACS this year. Of these, 838,000 will be for MI and 670,000 will be for unstable angina.26 Since >16% of patients with MI have a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <40%,38 thousands of individuals are annually at increased risk of cardiac arrest.

Ischemia and reperfusion, which occur commonly during the early phases of MI, are clearly associated with arrhythmias. Because only 20% of cardiac arrests involve an acute infarction, it has been assumed that transient ischemia rather than infarction has a major role in triggering sudden death. Transient systemic factors, such as hypoxia, hypotension, acidosis, or electrolyte abnormalities, can affect electrophysiologic stability and susceptibility to arrhythmias. However, a vigilant search should be made for an underlying cause of arrhythmia even in the setting of electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia, which may be a cause or consequence of cardiac arrest.39

Congenital or acquired arrhythmias are a known risk factor for cardiac arrest. Unfortunately, the severity of risk is not well defined because of the many associated factors that may confound evaluation of a particular patient. Deaths in athletes have drawn considerable public interest to this problem. Although known arrhythmias increase the chance of cardiac arrest, the degree to which various arrhythmias do so is difficult to predict precisely. Screening of athletes for risk of arrhythmia lacks sensitivity and specificity.40

Age, Race, and Traditional Risk Factors

The rate of cardiac arrest increases exponentially with increasing age. The rates for cardiac arrest are substantially higher at any given age for men than for women. Since there are more women in the population than older men, the overall incidences by gender are similar. However women are at less risk at any particular age.

Race is an important risk factor for many CVDs. Blacks have a higher rate of hypertension, LV hypertrophy, renal disease, and diabetes than do whites. As a consequence of these differences in the distribution of risk factors, the incidence of cardiac arrest is significantly higher among blacks than among whites.41

Hypertension predisposes patients to develop CAD, cardiac hypertrophy, congestive heart failure, stroke, renal disease, and sudden death. The risk is continuous, without

evidence of a threshold, down to blood pressures as low as 115/75 mm Hg.42 Twofold to threefold increases in CAD are seen in patients with systolic blood pressures above 160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressures above 95 mm Hg.43 Hypertension affects about 65 million persons in the United States44 and affects >90% of individuals at some time during their lives.45 As many as two-thirds of affected Americans are untreated or undertreated.46

evidence of a threshold, down to blood pressures as low as 115/75 mm Hg.42 Twofold to threefold increases in CAD are seen in patients with systolic blood pressures above 160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressures above 95 mm Hg.43 Hypertension affects about 65 million persons in the United States44 and affects >90% of individuals at some time during their lives.45 As many as two-thirds of affected Americans are untreated or undertreated.46

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree