Fig. 68.1

CT scan image of liver cirrhosis (Courtesy of Dr. Eric Yasumoto)

Question

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Answer

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis leading to septic shock.

All patients with the presence of cirrhosis and ascites, who are symptomatic with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting or fever, should be suspected as having spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) and should undergo a paracentesis and be treated with antibiotics, regardless of their ascitic fluid polymorphonuclear (PMN) count until ascitic fluid culture results are available [1, 2]. It is important to rule out a secondary etiology for peritonitis such as a surgical cause. In this case, the patient had a CT of the abdomen which did not indicate a surgical etiology. Differentiating between SBP and secondary bacterial peritonitis is further covered under the diagnosis section of this chapter.

This patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for septic shock secondary to presumed SBP. He was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and was continued on norepinephrine. He was also given albumin 1.5 g/kg on the first day of admission. He continued to have fevers, but his hemodynamics progressively improved.

On the third day of ICU admission, his blood pressure normalized and vasopressor support was discontinued. His ascitic fluid cultures grew Escherichia coli sensitive to Cefotaxime, and his antibiotic coverage was subsequently narrowed. He was also given his second dose of albumin (1 g/kg). The patient was extubated later that day and was transferred out of the ICU in stable condition to continue an antibiotic course of 5 days followed by prophylaxis with a daily fluoroquinolone.

Principles of Management

Since the initial description of SBP in the 1960s, studies have reflected better management and earlier recognition resulting in a marked reduction in mortality from 90 % quoted in some older studies to now a predominantly treatable complication of decompensated cirrhosis. Although cases of SBP have been reported in patients with nephrotic syndrome and congestive heart failure, it is most prevalent in patients who have advanced cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Different variants of SBP and ascitic fluid infections have been characterized and are important to recognize [1, 3–5].

Diagnosis

All patients with cirrhosis and ascites have a high risk of developing SBP; therefore a paracentesis should be performed to rule out SBP for all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites (Fig. 68.2). This has been proven to reduce mortality [1, 6, 7]. There are several additional criteria which suggest an increased risk of developing SBP and in these patients, the suspicion for SBP should be even higher: ascitic fluid total protein level of <1.0 g/dl, prior history of SBP, a serum total bilirubin >2.5 mg/dl, concomitant variceal bleeding, and recent use of a proton pump inhibitor [1, 3, 8].

Fig. 68.2

Ultrasound images of ascitic fluid (arrow) (Courtesy of Dr. Eric Yasumoto)

The ascitic fluid should be sent for aerobic and anaerobic cultures, cell count and differential, and fluid chemistries (albumin, protein, glucose, lactate dehydrogenase, amylase, and in some cases bilirubin). It is important that diagnostic paracentesis be performed prior to the administration of antibiotics. The yield of the ascitic fluid cultures is greatly reduced even with the administration of a single dose of broad-spectrum antibiotics within 6 h prior to the paracentesis [1, 2, 7]. Appropriate handling of the ascitic fluid is crucial to minimize the risk of skin flora contaminating the cultures, and to avoid obtaining a false-positive culture. When culturing ascitic fluid, immediate bedside inoculation of the ascitic fluid into routine blood culture bottles with at least 10–20 ml of fluid has been shown to increase the sensitivity of cultures and to avoid false negative results [1, 9].

A total absolute neutrophils count of >250 cells/mm3, a positive ascitic fluid bacterial culture and absence of secondary causes of peritonitis (i.e. bowel perforation) usually confirm the diagnosis of SBP [1]. However, different variants of spontaneous ascitic infections exist which may not present with the classic neutrophil count. These are depicted in Table 68.1.

Table 68.1

Characterization of ascitic fluid infections

Type of infection | PMN cell count (/mm3) | Bacterial culture result |

|---|---|---|

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | ≥250 | Positive (usually 1 organism) |

1. Culture-negative neutrocytic ascites | ≥250 | Negative |

2. Monomicrobial nonneutrocytic bacterascites | <250 | Positive (1 organism) |

3. Polymicrobial bacterascites | <250 | Positive (polymicrobial) |

Secondary bacterial peritonitis | ≥250 (usually in the thousands) | Positive (polymicrobial) |

It is imperative to rule out secondary bacterial peritonitis, such as due to bowel perforation or intra-abdominal abscess, prior to diagnosing SBP. Failure to correctly diagnose secondary bacterial peritonitis from a surgical etiology can be catastrophic. Several findings can help differentiate SBP from a secondary bacterial peritonitis caused by perforation. SBP is often associated with less abdominal pain, lower ascitic fluid total protein levels, a lower ascitic fluid neutrophil count (<1000 cells/mm), lower ascitic fluid bilirubin levels (<6.0 mg/dl), normal or low ascitic fluid amylase levels (higher levels correlate with a perforation), and the presence of a monomicrobial culture result [10]. The presence of two of the three following “Runyon criteria” is very sensitive for the diagnosis of secondary bacterial peritonitis: ascitic fluid total protein >1.0 g/dl; glucose of <50 mg/dl; and an elevated serum LDH in the presence or absence of a polymicrobial blood culture [1, 10]. In the event that a patient that was initially diagnosed as having SBP is not clinically improving, a repeat paracentesis may be helpful as a rising ascitic fluid neutrophil count is highly concerning for secondary bacterial peritonitis. The presence of less common pathogenic bacteria (see below) or fungal growth in the ascitic cultures should also prompt a search for an intraabdominal abscess leading to secondary peritonitis.

Marked peripheral leukocytosis (or neutrophilia) does not seem to have an effect on the leukocyte (or neutrophil) count in ascitic fluid [11]. However, a traumatic paracentesis leading to hemorrhagic ascites fluid may alter the neutrophil count. The commonly used correction factor is to subtract 1 neutrophil for each 250 red blood cells/mm3 in the ascitic fluid [12].

Microbiologic Etiology

Several explanations exist for how bacteria enter the ascitic fluid and lead to infection. The most widely accepted mechanism is that of translocation of gut bacteria across the leaky intestinal wall of cirrhotic patients into the mesenteric lymph nodes with subsequent seeding of the ascites [3, 13]. Intestinal bacterial overgrowth, either due to decreased intestinal motility or through the use of proton pump inhibitors has also been proposed but remains controversial [1, 3, 8, 14]. The bacteria that usually result in SBP are those that require a functionally intact immune system with adequate complement levels for opsonization and removal. Advanced cirrhosis certainly reduces the function of the complement system and phagocyte activity [3, 15].

Most cases of SBP are due to gut bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella; however Streptococcus pneumonia, Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas infections can also occur. Additional bacterial pathogens have geographic prevalence such as Aeromonas hydrophila, which is seen in Korea [16]. The presence of more than one type of bacteria in the ascitic fluid should prompt a consideration for a secondary peritonitis. Additionally, unusual organisms such as fungi found on culture analysis of the ascitic fluid can also suggest a secondary bacterial peritonitis from an abscess. There have also been case reports of spontaneous fungal peritonitis [17] and SBP due to Listeria monocytogenes [18], in immune-suppressed and elderly patients, respectively.

Treatment

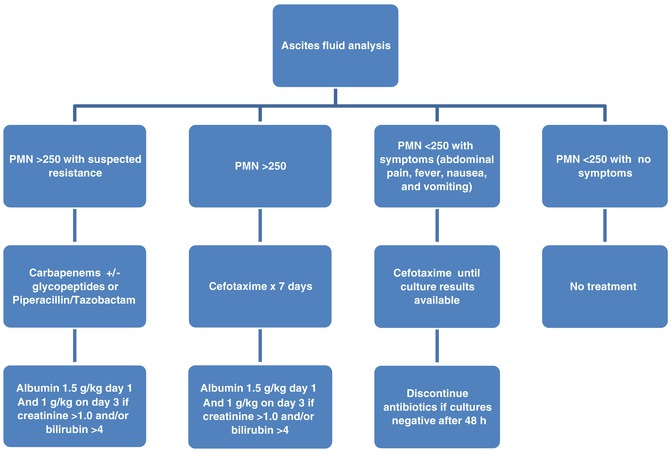

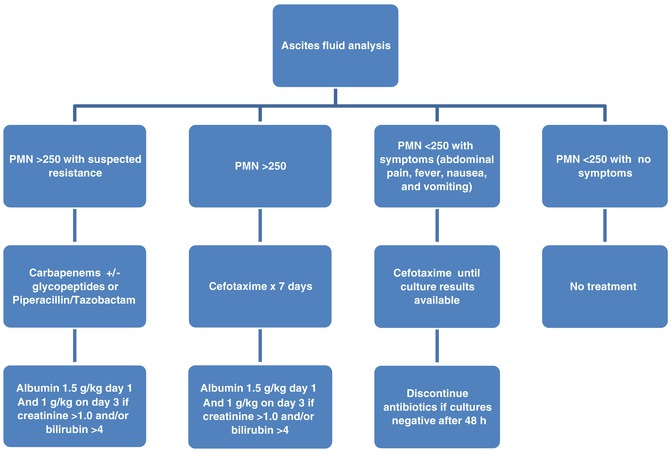

All patients with SBP should be started on broad spectrum antibiotics as soon as the diagnosis is suspected. Appropriate and timely treatment has been shown to significantly decrease morbidity and mortality [1, 7, 14]. Figure 68.3 is a useful table to help guide therapy in patients with suspected or confirmed SBP.

Fig. 68.3

Algorithm for initial management of suspected spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Antibiotics

In patients with cirrhosis and ascites who have elevated temperature greater than 37.8 °C or 100 °F, abdominal pain, altered mental status, or evidence of sepsis, treatment for SBP should be initiated as soon as ascitic fluid, blood, and urine have been obtained for culture and analysis [1, 14, 19]. In patients without these findings, it is reasonable to wait until the results of the PMN count are available, with subsequent initiation of treatment if the ascitic fluid PMN count is ≥250 cells/mm3. Collection and processing of the ascitic fluid should be done rapidly from the time of patient presentation and suspicion of SBP. The ascitic fluid PMN count is more readily available than the culture results and can reliably identify patients who need empiric antibiotic coverage [6].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree