The most common risk factor for spontaneous pneumothorax is smoking, although chronic lung disease and infections are predisposing factors.

![]() History of prior pneumothorax is common since 20% to 30% of patients experience recurrence.

History of prior pneumothorax is common since 20% to 30% of patients experience recurrence.

![]() Iatrogenic pneumothorax occurs secondary to invasive procedures such as transthoracic needle biopsy (50%), subclavian line placement (25%), nasogastric tube placement, or positive pressure ventilation; post-procedure chest radiograph should always be performed to assess for this complication.

Iatrogenic pneumothorax occurs secondary to invasive procedures such as transthoracic needle biopsy (50%), subclavian line placement (25%), nasogastric tube placement, or positive pressure ventilation; post-procedure chest radiograph should always be performed to assess for this complication.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

![]() Pneumothorax likely occurs after rupture of a sub-pleural bulla allows air to enter the potential space between the parietal and visceral pleura, leading to partial lung collapse.

Pneumothorax likely occurs after rupture of a sub-pleural bulla allows air to enter the potential space between the parietal and visceral pleura, leading to partial lung collapse.

![]() Tension pneumothorax is caused by positive pressure in the pleural space leading to decreased venous return, hypotension, and hypoxia.

Tension pneumothorax is caused by positive pressure in the pleural space leading to decreased venous return, hypotension, and hypoxia.

CLINICAL FEATURES

![]() Symptoms resulting from a pneumothorax are directly related to the size, rate of development, and underlying lung disease.

Symptoms resulting from a pneumothorax are directly related to the size, rate of development, and underlying lung disease.

![]() Most patients complain of acute onset pleuritic pain and have diminished breath sounds on the affected side.

Most patients complain of acute onset pleuritic pain and have diminished breath sounds on the affected side.

![]() Large volume pneumothoraces cause dyspnea, tachycardia, hypotension, and hypoxia.

Large volume pneumothoraces cause dyspnea, tachycardia, hypotension, and hypoxia.

![]() Clinical signs of tension pneumothorax include tracheal deviation, hyperresonance, and hypotension.

Clinical signs of tension pneumothorax include tracheal deviation, hyperresonance, and hypotension.

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL

![]() Electrocardiographic changes, including ST changes and T-wave inversion, may be seen with pneumothorax.

Electrocardiographic changes, including ST changes and T-wave inversion, may be seen with pneumothorax.

![]() The standard diagnostic modality, an upright poster-oanterior chest radiograph (Fig. 34-1), is only 83% sensitive.

The standard diagnostic modality, an upright poster-oanterior chest radiograph (Fig. 34-1), is only 83% sensitive.

![]() Expiratory films are no more sensitive than a PA chest radiograph.

Expiratory films are no more sensitive than a PA chest radiograph.

![]() CT scan is more sensitive than plain radiography, and is helpful in distinguishing between a large bulla and a pneumothorax.

CT scan is more sensitive than plain radiography, and is helpful in distinguishing between a large bulla and a pneumothorax.

![]() The sensitivity of ultrasound is near 100%. Sonographic signs include absence of lung sliding, demonstration of a “lung point,” and absence of normal vertical comet-tail artifacts (Fig. 34-2).

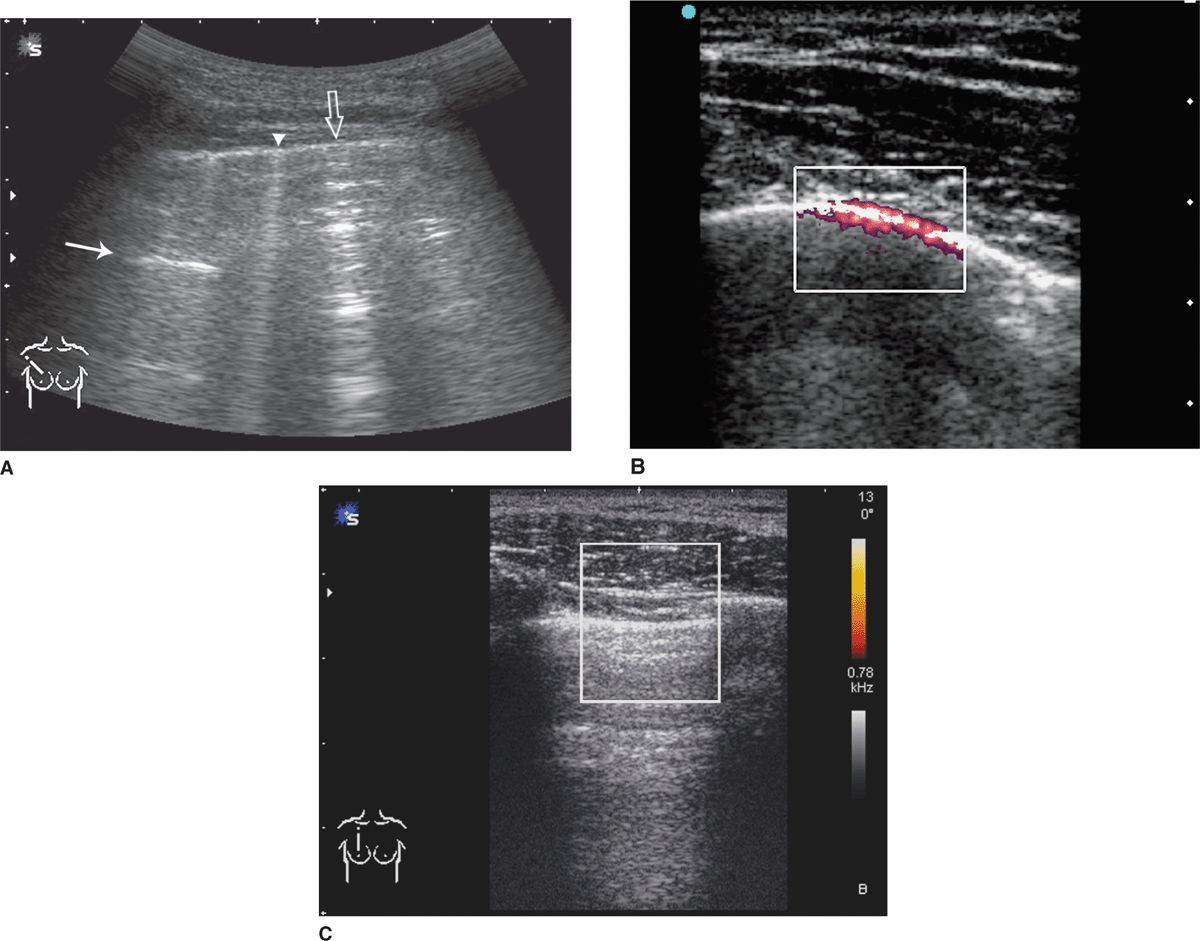

The sensitivity of ultrasound is near 100%. Sonographic signs include absence of lung sliding, demonstration of a “lung point,” and absence of normal vertical comet-tail artifacts (Fig. 34-2).

![]() Differential diagnosis includes costochondritis, angina, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, pericarditis, pleurisy, pneumonia, and aortic dissection.

Differential diagnosis includes costochondritis, angina, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, pericarditis, pleurisy, pneumonia, and aortic dissection.

FIG. 34-1. Spontaneous hemopneumothorax. Upright chest radiograph of a 19-year-old male college student with spontaneous hemopneumothorax. Note the large air-fluid level in the inferior portion of the right hemithorax in addition to the complete collapse of the entire right lung. In spite of reexpansion of the collapsed lung after thoracostomy tube placement, the patient experienced persistent bleeding. After 1 L of blood loss from the chest, emergent thoracotomy was required for control of hemorrhage from a vessel along the apical parietal pleura.

FIG. 34-2. Ultrasonography (US) of normal lung and pneumothorax. A. Normal lung artifacts. The A-line (arrow) represents the horizontal reverberation artifact generated by the parietal pleura (line shown by arrowhead and open arrow). Comet-tail artifacts arise from the pleura and project to the depth of the image. They move back and forth along the pleura in real time and may vary between a narrow (arrowhead) and a wider (open arrow) appearance. B. Power Doppler with color gain set low, normal lung appearance. Color highlights the movement of the parietal and visceral pleura interface. C. US of pneumothorax. Absence of lung movement on power Doppler. No sliding movement seen in real time; comet-tail artifacts replaced by horizontal airy artifacts.

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT CARE AND DISPOSITION

![]() Oxygen 3 to 10 L by nasal cannula helps increase resorption of pleural air.

Oxygen 3 to 10 L by nasal cannula helps increase resorption of pleural air.

![]() For patients with small pneumothoraces and no known lung disease treatment, options include the following:

For patients with small pneumothoraces and no known lung disease treatment, options include the following:

1. Observation for 6 hours and outpatient surgical follow-up within 24 hours if there is no enlargement on radiograph.

2. Aspiration using a needle or catheter (<14 gauge) followed by immediate removal of the device, 6 hours of observation, and surgical follow-up if there is no recurrence. This method has a success rate reported as 37% to 75%.

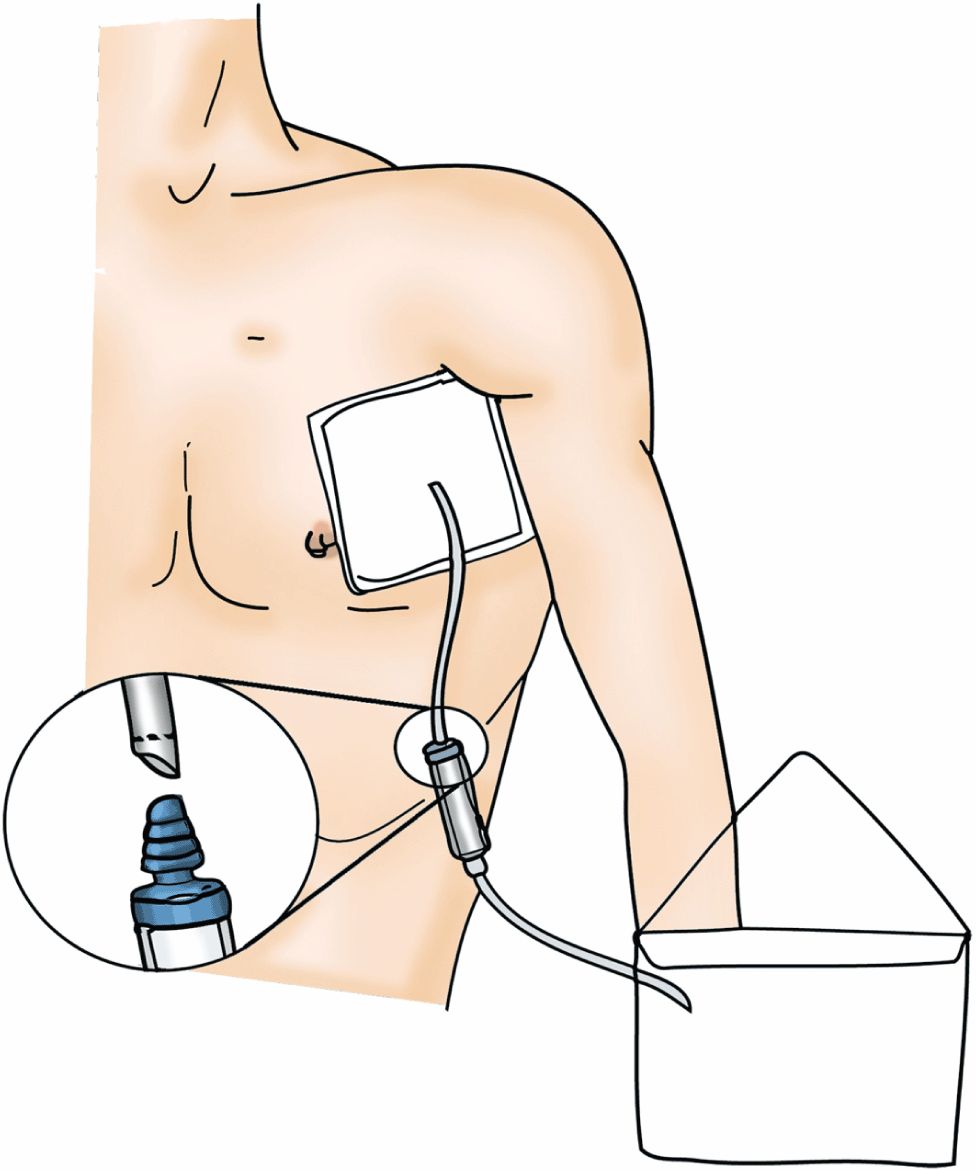

3. Placement of a small catheter (<14 F) or chest tube (10–14 F) and admission. Consider use of Heimlich valve with this approach (see Fig. 34-3).

![]() In patients with small pneumothoraces and known lung disease, a small catheter (<14 F) or chest tube (10–22 F) should be placed. Consider use of Heimlich valve (see Fig. 34-3).

In patients with small pneumothoraces and known lung disease, a small catheter (<14 F) or chest tube (10–22 F) should be placed. Consider use of Heimlich valve (see Fig. 34-3).

![]() Moderate- (16–22 F) or large- (24–36 F) sized tube tho-racostomy with water seal drainage is indicated for any large or bilateral pneumothorax, or for hemothorax.

Moderate- (16–22 F) or large- (24–36 F) sized tube tho-racostomy with water seal drainage is indicated for any large or bilateral pneumothorax, or for hemothorax.

![]() In unstable patients (those with tension pneumothorax or pneumothorax with severe underlying lung disease), needle thoracostomy followed by tube tho-racostomy should be performed before radiography.

In unstable patients (those with tension pneumothorax or pneumothorax with severe underlying lung disease), needle thoracostomy followed by tube tho-racostomy should be performed before radiography.

![]() Helicopter transport, general anesthesia, or mechanical ventilation may also be indications for tube thoracostomy.

Helicopter transport, general anesthesia, or mechanical ventilation may also be indications for tube thoracostomy.

![]() Treatment for iatrogenic pneumothorax follows the above general principles.

Treatment for iatrogenic pneumothorax follows the above general principles.

![]() The treatment complication of reexpansion pulmonary edema is rare; it tends to occur more commonly in those aged 20 to 39 years, those with large pneumothoraces, and those with a pneumothorax that has been present for more than 72 hours prior to lung reexpansion.

The treatment complication of reexpansion pulmonary edema is rare; it tends to occur more commonly in those aged 20 to 39 years, those with large pneumothoraces, and those with a pneumothorax that has been present for more than 72 hours prior to lung reexpansion.

FIG. 34-3. Illustration of catheter or tube with Heimlich valve placement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree