CHAPTER 52 SPLENIC INJURIES

The spleen has had a prominent role in medical theory and practice throughout history. The Greeks and Romans believed that the spleen played a role in filtering the humors of the body, mirroring some of our modern concepts. During the middle of the last millennium, the Thuggee was a cult that worshipped Kali, a Hindu goddess of destruction. The members were professional assassins, and the act of murder for pay was an act of worship for their goddess. They were most famous for their use of the noose, but also targeted the left upper quadrant where, often fragile and swollen from malaria, the spleen lay. A well-placed blow leading to splenic rupture and bleeding in the absence of available transfusion and modern surgery might well prove fatal.

INCIDENCE AND MECHANISM OF INJURY

The spleen is listed, along with the liver, as either the first or second most commonly injured solid viscus in the abdomen after blunt trauma. Because splenic injuries have a tendency to demonstrate themselves clinically more often than do hepatic injuries, splenic injury was listed as the most commonly injured intra-abdominal solid viscus before the advent of computed tomography (CT) scanning. After the advent of CT scanning and our ability to better diagnose clinically silent intra-abdominal injuries, it became apparent that the liver is also commonly injured and some series now list hepatic injuries as more common than splenic injuries. One large, multi-institutional study showed a 2.6% incidence of splenic injuries (6308 of 227,656 patients) for all patients evaluated for trauma, with splenic injury confirmed by either laparotomy or computed tomography.1

For penetrating trauma, retrospective reviews of two large centers, Grady Memorial Hospital and Ben Taub General Hospital, showed the incidence of splenic injury from abdominal gunshot wounds to be 7%–9%, far less than for the hollow organs and the liver.2,3 Injuries to the spleen from stab wounds are even more infrequent.

Splenic bleeding can also occur on a delayed basis, a phenomenon of obvious importance in patients treated nonoperatively. The incidence of delayed bleeding, leading to failure of nonoperative therapy, varies depending on the grade of the injury. The failure rate of nonoperative management in aggregate for a large multi-institutional study was 10.6%, but varied from 4.8% for grade I injuries to 75% for grade V injuries.1 One hypothesis for the pathophysiology leading to delayed rupture and bleeding is that as subcapsular clot breaks down several days after injury into its component parts, the number of osmotically active particles in the area increases and draws more fluid into the area of injury. The resultant increase in size of the area may then rupture the capsule, leading to renewed bleeding. Even without being trapped under the capsule of the spleen, the inflammation and fibrinolysis in and around the healing injury and clot may weaken the clot enough to result in renewed hemorrhage.

DIAGNOSIS

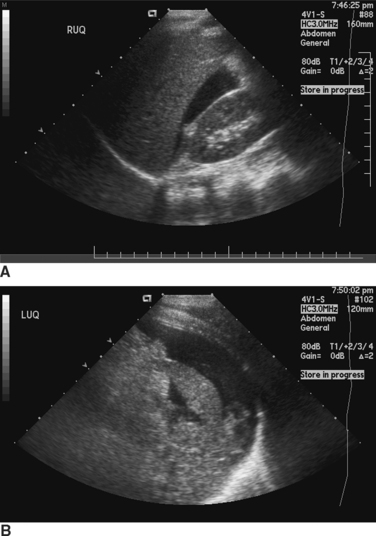

Ultrasound of the abdomen for free fluid, the so-called FAST (focused assessment with sonography for trauma) examination, is being used increasingly as a means of diagnosing hemoperitoneum in blunt trauma patients. Like DPL, it is most useful in unstable patients. Also, as with peritoneal lavage, the ability of ultrasound to determine exactly what is bleeding in the peritoneal cavity is limited. Attempts to image specific organ injuries using ultrasound have met with limited success. The most common method of using FAST examinations is for detection of intraperitoneal fluid and as a determinant of the need for either further imaging of the abdomen or for emergency surgery (Figure 1).

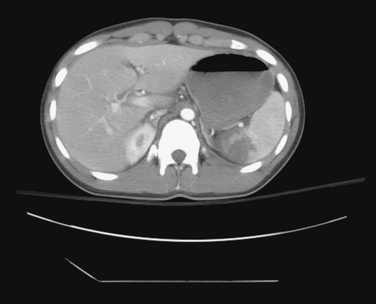

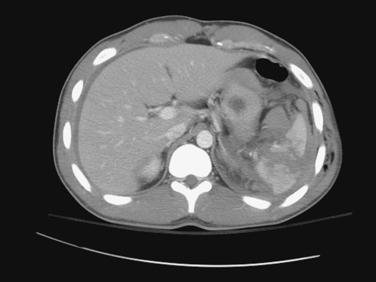

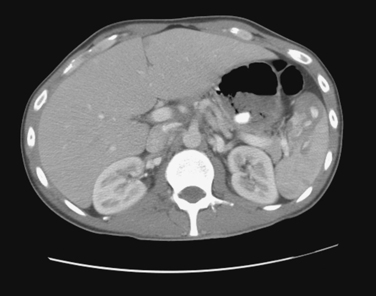

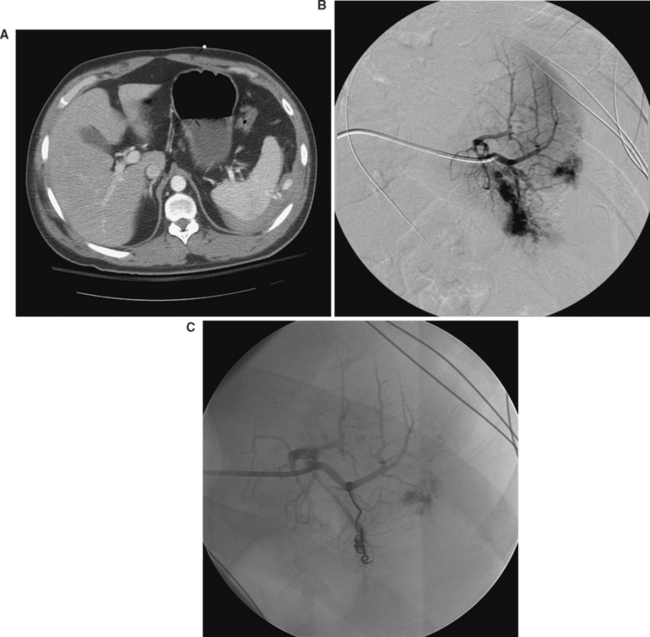

CT of the abdomen is the dominant means of nonoperative diagnosis of splenic injury (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Patients are sent either directly for abdominal CT scanning after initial resuscitation or are screened by abdominal ultrasonography as reasonable candidates for subsequent CT. When abdominal CT scanning is done, intravenous contrast is quite helpful in diagnosis; oral contrast is less helpful and does not measurably increase the sensitivity of CT for splenic injury detection.

A CT finding in the spleen that has received a great deal of attention is the presence in the disrupted splenic parenchyma of a “blush,” or hyperdense area with a collection of contrast in it. When present, a blush is thought to represent ongoing bleeding with active extravasation of contrast. There is reasonably convincing evidence that the presence of a blush correlates with an increased likelihood of continued or delayed bleeding from the splenic parenchyma. Such a finding therefore has important implications with respect to either operative intervention or the use of angiographic splenic embolization to stop ongoing bleeding (Figure 5).

Anatomic Location of Injury and Injury Grading: American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Organ Injury Scale

A number of different grading systems have been devised to quantify the degree of injury to the spleen. These systems have been created based both on the computed tomographic appearance of ruptured spleens as well as the intraoperative appearance of the spleen. The best known splenic grading system is the one created by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) (Table 1).4 Implicit in the AAST grading system are the perhaps fairly obvious concepts that grade increases with an increase in either the length or depth of parenchymal injury, injury to the hilum, or injuries to multiple areas of the spleen.

Table 1 American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Organ Injury Scaling: Splenic Injury Grading

| Gradea | Injury Type | Description of Injury |

|---|---|---|

| I | Hematoma | Subcapsular, <10% surface area |

| Laceration | Capsular tear, <1 cm parenchymal depth | |

| II | Hematoma | Subcapsular, 10%–50% surface area |

| Laceration | Capsular tear, 1–3 cm parenchymal depth that does not involve a trabecular vessel | |

| III | Hematoma | Subcapsular, >50% surface area or expanding; ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal hematoma; intraparenchymal hematoma 5 cm or expanding |

| Laceration | >3-cm parenchymal depth or involving trabecular vessels | |

| IV | Laceration | Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels producing major devascularization (>25% of spleen) |

| V | Laceration | Completely shattered spleen |

| Vascular | Hilar vascular injury which devascularizes spleen |

a Advance one grade for multiple injuries, up to grade III.

Adapted from Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Jurkovich GJ, et al: Organ injury scaling: spleen and liver. J Trauma, 38:323, 1995.

The CT and intraoperative appearances of a splenic injury are often different from one another. Some of these differences might be because of evolution of the injury between the time of CT scanning and operation, but it is also likely that CT scanning is imperfect in describing the pathologic anatomy of a splenic rupture. Splenic injury scores based on CT scans can both overestimate and underestimate the degree of splenic injury seen at surgery. It is possible to have a CT appearance of fairly trivial injury but at surgery find significant splenic disruption. Conversely, it is possible to see what looks like a major disruption of the spleen on CT scanning and not see the same kind of severity of injury at surgery. In general, the CT scan and associated scores tend, if anything, to underestimate the degree of splenic injury compared with what is seen at surgery.5

An important point about CT-based grading systems is that clinical outcome does not tightly correlate with the degree of injury seen on CT. Although there is a rough correlation between the grade of splenic injury seen on CT scanning and the frequency of operative intervention, exceptions are common. It is possible to have what looks like a fairly trivial injury on CT scan turn out to require delayed operative intervention. In contrast, severe looking splenic injuries on CT scan quite often follow a benign post injury course and are successfully managed nonoperatively.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree