Chapter 3

Social determinants of pain

On completion of this chapter readers will have:

1 A social determinants framework of the experience of pain.

2 An evidence-based theoretical framework encompassing these social determinants and a social communication model of pain.

3 An understanding of the application of social determinants to innovative prevention, assessment and intervention strategies.

OVERVIEW

Seeking ‘social causes’ of pain is consistent with the long history of interest in aetiological mechanisms for pain. Identifying causes of pain leads to more effective interventions. Causes conventionally have been approached through diagnosis of disease and injury, an approach endorsed by many researchers, healthcare professionals and parties responsible for health care and public policy. This approach is conventional wisdom and expected by patients in pain or living with chronic pain. Typical questions are ‘What injury or disease accounts for the pain?’ or ‘Is the source nociceptive or neuropathic?’. Such questions demonstrably neglect alternative major sources of pain and do not lead to numerous safe and efficacious interventions. The biopsychosocial model of health offers a broader approach which posits that all biological, psychological and social factors must be considered in understanding human health or illness (Engel 1977). Despite the substantial evidence supporting this position as it applies to pain (Gatchel et al 2007; Turk & Okifuji 2002), attention to biological phenomena overwhelms the field. Psychologically based approaches are often ignored by people with strong biomedical orientations, and social determinants of pain have received minimal attention (Blyth et al 2007; Morris 2010; Skevington & Mason 2004).

The position advocated here acknowledges the fundamental biological nature of pain. There have been major advances in understanding the cell biology consequences of tissue damage, genetic variability as a source of individual differences, biological transduction in nociceptive systems, peripheral and central nervous system impacts, and medical diagnosis and therapy for acute and intractable conditions. The dominant mechanistic theories of pain (specificity theory, pattern theory, summation theory, gate control theory, the neuromatrix perspective, neural plasticity and central sensitization, etc.) focus on these phenomena (Cope 2010). It is the search for complementary social causes of pain that occupies this chapter.

The focus on social processes appears particularly important in understanding human pain. Diverse patterns of adaptive behaviour supporting survival are evident across species, as biological systems evolve to sustain functioning in unique environments. In all animals, pain serves to warn about tissue damage and to motivate escape or avoidance behaviour. But pain can also come to acquire social functions and roles. Non-human mammals demonstrate an emergent capacity to utilize the social environment as a means of recognizing and avoiding danger and providing protective care (de Waal 2009). Human capacities for social engagement extend the likelihood that the social environment is particularly important in providing protection from pain. It is not clear whether the human brain evolved because of the challenges of life in complex social environments or an evolved brain permitted the complex adaptations of human attachment, cooperation and communal living, but these are integral features of all facets of human experience and living. One unique feature of the human brain is its ability to allow penetrating inferences concerning the emotions and intentions of other persons. Human adaptations reflect the necessity and complexity of interpersonal interaction, including its challenges and opportunities. The provision of care incorporating complex technological and healthcare system arrangements perhaps epitomizes social engineering in the interests of minimizing pain and suffering. It is not surprising that these unique human social capabilities should be integrated with pain experience and its expression, and one would expect the human pain system to have adapted accordingly.

THE SOCIAL COMMUNICATION MODEL OF PAIN

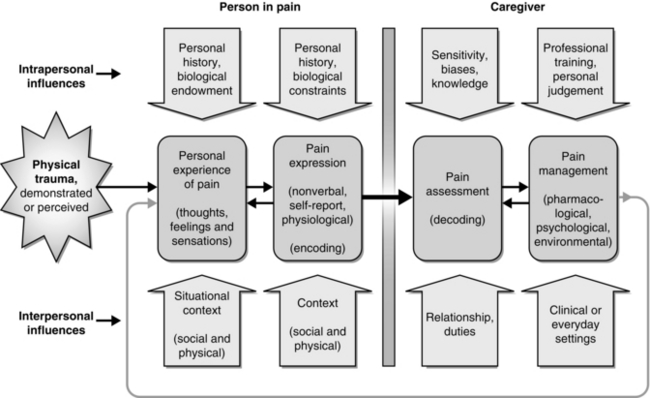

The social communication model of pain provides a detailed framework for understanding the complex interactions among the biological, psychological and social factors of pain (Craig 2009) (see Fig. 3.1). The following features of the model are examined here in sequence: sources of pain, the experience of pain, how pain is communicated to others and how others recognize, interpret and respond to information about the person’s pain. The process is recognized as dynamic and recursive. Each stage has an impact on whether the individual or others come to control the pain and whether the pain persists. Intrapersonal (biological and psychological) and interpersonal (social) factors are important at each stage. Unlike most models of pain, attention is devoted to the role of the caregiver and the social and healthcare policies they represent, given their importance if care is to be provided to the person in pain. At all stages, attention to social processes provides opportunities to delivering preventive care or interventions. One could attend to those social circumstances that lead to the presence of pain, its exacerbation, over- or under-reaction to the event, the intentional or unintentional infliction of pain by others, or the failure to use interventions that would minimize pain and suffering, among many other possibilities.

Fig. 3.1 The social communication model of pain. A conceptual model integrating biological, psychological and social perspectives at the level of interaction between the person in pain and persons present. Adapted from Craig K D, Korol C T 2008 Developmental issues in understanding, assessing, and managing pediatric pain. In: Walco G, Goldschnieder K (eds) Pain in Children: a practical guide for primary care, pp 9–20, fig 2.1. Humana Press Inc, With kind permission of Springer Science + Business Media.

SOURCES OF PAIN: OPPORTUNITIES FOR PREVENTION

Social circumstances often dictate whether people will be exposed to injury or disease. Therein lie opportunities for engaging in primary prevention, precluding the likelihood of pain before it happens. Epidemiological approaches to studying the distribution and determinants of pain have identified sociodemographic variations, social risk factors and population health trends in the prevalence and care of diverse painful conditions (von Korff & LeResche 2005). In establishing the complex web of causation, opportunities for prevention emerge. For example, oestrogen therapy for postmenopausal adult women is associated with increased risk of temporomandibular disorder (LeResche et al 1997). Awareness of this relationship contributes to cost–benefit analysis of hormone replacement therapy, perhaps decreasing the incidence of this painful condition. In this manner, social factors, public awareness and policy may have an impact on use of a biomedical intervention strategy for chronic pain.

Characterization of social origins or risk factors has received minimal attention, despite interests of epidemiologists in risk and ecological factors (Dworkin et al 1992). Major categories of social risk factors can be conceptualized (see Box 3.1). The illustrations are not exhaustive; they are designed to highlight potential social causes of pain across the major social contexts of people’s lives. The balance between interpersonal and intrapersonal control of these sources of pain is not always evident. Some events may be the consequence of personal decisions of the person in pain, such as risk taking in dangerous sports, but social pressures and constraints influence such decisions. Pain imposed by others in the interests of the person, but entered voluntarily, is perhaps best typified by medical procedures, including medical prophylaxis, diagnosis and treatment (including surgery). Medical pain usually is construed as an undesirable, but inevitable, event. Nevertheless, recent interpretations increasingly characterize pain as an adverse event and argue that more should be done to preclude or mitigate pain (Chorney et al 2010). Pharmaceutical, psychological and environmental interventions can prevent or minimize immediate pain and the long-term consequences arising from medical procedures. For example, substantial neonatal exposure to pain is often characterized as the inevitable consequence of risk factors associated with preterm delivery, very low birth weight or congenital conditions. Nevertheless, there is reason to believe that exposure to pain is often unnecessarily excessive and disposes to adverse pain experience and behaviour later in life (Grunau & Tu 2007). Similarly, early life experience of dental pain predisposes children and adults to dental fears and avoidance of treatment (Versloot & Craig 2009). Thus, social factors again appear responsible for the risks associated with painful exposure and its consequences early in life.

Painful experiences also may be maintained or exacerbated by social events. Stress accompanies both daily life and periods of major social adjustment, and can contribute directly to psychophysiological disorders, lower immune functioning and promote tumour growth. This may compromise healing, thereby contributing to the manifestation, exacerbation and preservation of painful diseases and injuries (Antoni et al 2006). Stressful family, employer or other relationships tend to have a negative impact on coping and result in increased healthcare utilization. Under this strain, there is potential for vicious circles of family conflict, dysfunctional relationships, unemployment and social isolation that in turn perpetuate stress and pain. Alleviating circumstances creating stress for the individual can have an impact on the experience and expression of pain.

In general, healthcare systems that promote health provide a multifaceted and sustainable means of addressing pain. The major advances in preventive health care, including immunization programmes and public sanitation, dramatically diminish exposure to pain and suffering associated with infectious diseases. Similarly, injury prevention programmes are effective in reducing the incidence of painful injury (Pike et al 2010). Advertising campaigns, legal regulations and required certification and training all serve as preventive measures to diminish exposure to pain. Many examples of socially oriented programmes, such as ensuring a safe food supply and reducing tobacco use and alcohol abuse, have yielded long-term benefits, including reduction of health costs and the experience of pain. Thus, attention to healthcare policies and public education can be of considerable importance.

THE EXPERIENCE OF PAIN

An individual’s life history and current social environment determine the thoughts and feelings experienced during a painful event. Substantial, and sometimes dramatic, variations in how people describe and react to apparently comparable disease and injuries are well documented (Fillingim 2010; Mogil 1999). This variability is usually represented as unidimensional; some people respond with considerable stoicism whereas others react with hysterical distress. Such representation fails to reflect the richness of the cognitive, emotional and sensory features of painful experience (Williams et al 2010). Complex thoughts reflecting prior experiences, the current context and solutions to the challenges invariably accompany all painful experiences, including ‘What’s happening to me?’, ‘How serious is this?’, ‘Will it last long?’ and ‘What can I do?’ People vary in the extent to which they attend to bodily sensations, perceive painful experiences as varying in severity, and use personal and social schema to interpret their experiences. In addition, emotional distress, such as anxiety or depression, greatly varies among patients. Of particular importance are maladaptive patterns of thinking, such as catastrophizing (Sullivan et al 2004), and hypervigilance (Van Damme et al 2010) or emotional reactions, such as anxiety or fear avoidance (Vlaeyen & Linton 2000), which exacerbate and maintain dysfunctional pain and pain-related disability, and influence the ability to benefit from treatment.

Although individual variations are popularly described in terms of intrapersonal factors (e.g. ‘the person is “anxious” or “catastrophizing”’), these emotional reactions can have origins in biological inheritance and life experience. The biological features of pain are of unquestioned importance (Mogil 1999). They can be ‘hardwired’, as exemplified by the capacity of even the prematurely born neonate to signal pain (Craig et al 1993; Grunau & Craig 1987

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree