Chapter 4

The psychology of pain

models and targets for comprehensive assessment

On completing this chapter readers will have an understanding of the following:

1 The distinction between pain and chronic pain.

3 Biopsychosocial models of pain.

4 Cognitive constructs associated with beliefs, mood, anxiety and fear.

5 Behavioural constructs related to avoidance, activity limitation, coping behaviour, pain and suicide.

6 Environmental influences of family, culture and ethnicity, socioeconomic factors and work.

OVERVIEW

In this chapter we review the current state of knowledge regarding the psychology of pain as it can be applied to assessment planning and case conceptualization. We provide definitions of pain and chronic pain, summarize important features of a historical model that provided the foundation for contemporary biopsychosocial approaches to understanding pain, selectively highlight important cognitive constructs and pain behaviours as well as environmental influences, and conclude with a summary of important considerations in assessment planning and case conceptualization. This approach is predicated on the position that assessment and case conceptualization should be a conceptually driven process (Asmundson & Hadjistavropoulos 2006; Taylor & Asmundson 2004); as such, empirically supported theoretical constructs and applications form the foundation upon which assessment, case conceptualization and subsequent treatment plans are built. Throughout we refer to current empirical findings and, as appropriate, incorporate examples to illustrate salient points.

PAIN AND CHRONIC PAIN DEFINED

Pain is currently defined as a complex perceptual phenomenon that involves a number of dimensions, including, but not limited to, intensity, quality, time course and personal meaning (Merskey & Bogduk 1994). It is adaptive in the short term, facilitating the ability to identify, respond to and resolve physical pathology or injury. Unfortunately, a significant number of people experience pain for periods that substantially exceed expected times for physical healing (e.g. Waddell 1987). When pain persists for 3 months or longer, it is considered chronic (e.g. International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) 1986) and, while not necessarily maladaptive (Asmundson et al 1998; Turk & Rudy 1987), often leads to physical decline, limited functional ability and emotional distress. These pain experiences are also associated with an increased probability of experiencing comorbid psychopathology (McWilliams et al 2003; for review, see Asmundson & Katz 2009), inappropriate use of medical services, reduced work performance or absenteeism, and high cost insurance claims (Spengler et al 1986; Stewart et al 2003). Translated into a dollar value, common chronic pain conditions cost the USA and Canada, respectively, approximately US$60 billion and CAN$6 billion dollars annually.

MODELS PERTINENT TO UNDERSTANDING PAIN

There are several contemporary pain models that are important in the context of assessment and case conceptualization. These models are similar in that they all recognize the interplay between biological, psychological and sociocultural factors in the pain experience. Below we highlight one model of considerable historical significance as well as primary features of various contemporary biopsychosocial models. Detailed descriptions of the social influences on pain are provided by Craig in this volume (Chapter 3).

Gate control theory

Melzack and colleagues’ seminal papers on the gate control theory of pain (Melzack & Casey 1968; Melzack & Wall 1965) are frequently cited as the first to integrate biological and psychological mechanisms of pain within the context of a single model. Melzack & Wall (1965) suggested that the passage of ascending nociceptive (pain) information from the body to the brain was controlled by a hypothetical gating mechanism within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The gating mechanism works as follows. Excitation along the large-diameter, myelinated fibres of the spinal cord closes the gate, whereas excitation along the small-diameter, unmyelinated fibres opens the gate. Transmissions about current cognition and mood descending from the brain to the gating mechanism also influence whether the gate is closed or opened. In short, the summation of information travelling along the different types of ascending fibres from the body with that travelling on descending fibres from the brain determines whether the gate is open or closed and, thereby, influences the perception of pain. Melzack & Casey (1968) further proposed that three different neural networks (i.e. sensory–discriminative, motivational–affective and cognitive–evaluative) influence the modulation of sensory input. The addition of these networks to the model allowed for ‘perceptual information regarding the location, magnitude, and spatiotemporal properties of the noxious stimulus, motivational tendency toward escape or attack, and cognitive information based on analysis of multimodal information, past experience, and probability of outcome of different response strategies’ (pp 427–428).

Time and empirical effort have led to advances in understanding the anatomy and structure of the gating mechanism proposed by Melzack and Wall (Price 2000; Wall 1996), as well as to elaborations of the neural network model (Melzack 1999; Melzack & Katz 2004; please refer to Chapter 6). Notwithstanding, the gate control theory challenged the primary assumptions of the traditional biomedical models. Rather than being exclusively conceptualized as sensation arising from physical damage, the experience of pain came to be viewed as a combination of both pathophysiology and psychological factors. As such, pain as well as pain-related cognitions and mood were no longer viewed as secondary reactions to physical damage. Instead, the pathophysiology of pain was conceptualized as having a reciprocal influence on cognitions and mood, and vice versa. It is this foundation from which contemporary biopsychosocial models emerged.

Biopsychosocial models

The biopsychosocial approach holds that the experience of pain is determined by the interaction between biological, psychological (e.g. cognition, behaviour, mood) and social (e.g. cultural) factors. A number of specific biopsychosocial models have been proposed over the past 35 years, including several behaviourally based models (Fordyce 1976; Fordyce et al 1982), as well as the more comprehensive cognitive–behavioural Glasgow (Waddell 1987; Waddell et al 1984) and biobehavioural (Turk 2002; Turk & Flor 1999; Turk et al 1983) models. Detailed descriptions of these models of pain are provided elsewhere (e.g. Asmundson et al 2004a; Asmundson & Wright 2004).

Despite differences with respect to specificity regarding behavioural and cognitive influences on pain, all of the biopsychosocial models share a common focus – the focus is not on disease per se but on illness, where illness is viewed as a type of behaviour (Parsons 1951). The concept of illness behaviour (Mechanic 1962) implies that individuals may differ in perception of and response to bodily sensations and changes (e.g. pain, nausea, heart palpitations), and that these differences can be understood in the context of psychological and social processes. For example, whereas one person may perceive pain as indicative of a potentially serious malady and solicit reassurances or assistance from others in even the most rudimentary of daily activities, another person may perceive similar pain as discomforting but harmless and work through the discomfort. Illness behaviour is considered a dynamic process, with the role of biological, psychological and social factors changing in relative importance as the condition evolves. While a condition may be initiated by biological factors, such as physical injury or pathology, the psychological and social factors may come to play a primary role in maintenance and exacerbation; indeed, the focus often shifts from pain to significant concern and anxiety about personal health and well-being (see, for example, Hadjistavropoulos et al 2001).

This focus is also shared in the more recent fear–avoidance models of chronic pain (Asmundson et al 1999, 2004a; Vlaeyen & Linton 2000), wherein pain-related fear and anxiety are suggested to play primary roles in the development and maintenance of disabling chronic pain. The fear–avoidance models are predicated on long-standing observations that fear and anxiety appear to be critical elements in the pain experience. Indeed, the association between fear and pain dates back to at least as early as Aristotle, who, over 2000 years ago, stated ‘Let fear, then, be a kind of pain or disturbance resulting the imagination of impending danger, either destructive or painful’, and is an important consideration in each of the biopsychosocial models described above. Since fear–avoidance models have stimulated some of the most recent developments with respect to assessment and case conceptualization for individuals who have pain lasting beyond the time typical for physical healing, we provide a more detailed description here.

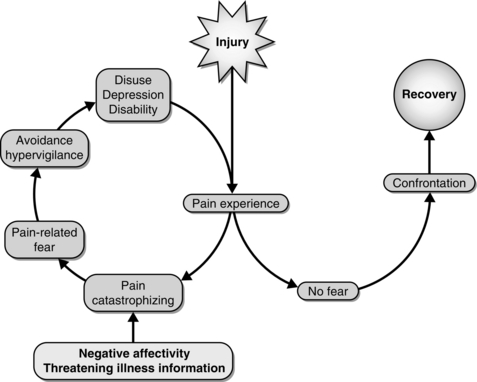

Contemporary fear-avoidance models of chronic pain are based primarily on the writings of several scholars (Asmundson et al 1999; McCracken et al 1992; Vlaeyen et al 1995; Waddell et al 1993), each of whom provided slightly different conceptualizations of the role of fear, anxiety, and avoidance in perpetuating pain. Subtle differences aside, the primary postulates of each of these scholars are captured in the model proposed by Vlaeyen & Linton (2000), and illustrated in Figure 4.1. This model can be summarized as follows. On perceiving pain, people make an appraisal of the meaning or purpose of the pain (pain experience). Most people appraise the pain to be unpleasant and discomforting but not indicative of serious threat to their well-being (no fear). These people then engage in appropriate behavioural restriction and graduated increases in activity (confrontation) until they have healed (recovery). However, some people appraise the pain as being indicative of a serious threat to their well-being (pain catastrophizing) and, influenced by predispositional and current psychological factors, spiral into a self-perpetuating cycle characterized by fear (i.e. fear of pain, fear of (re)injury), activity limitations, disability and pain. It is this latter group of people who experience pain that lasts beyond the time expected for normal healing.

Fig. 4.1 Fear-avoidance model. Reprinted from Vlaeyan, J.W.S., and Linton, S.J., Fear avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. PAIN® 2000, April 85(3); 317-332. This figure has been reproduced with permission of the International Association for the study of Pain® (IASP). The figure may not be reproduced for any other purpose without permision.

This model has served as a useful platform upon which considerable amounts of empirical research and related practical applications have been based (for review of findings current to the beginning of this millennium, see Vlaeyen & Linton 2000; for review of more recent findings, see Leeuw et al 2007; for review of empirically supported treatment options, see Bailey et al 2010). In addition to advances in empirical findings and practical applications to this field of inquiry, there has been continuing refinement of the contemporary fear-avoidance model (e.g. Asmundson et al 2004a; Norton & Asmundson 2003).

COGNITIVE CONSTRUCTS

Beliefs

Pain beliefs are a broad category of ideations, often catastrophic in nature, held by all people, not just those with chronic pain (van Damme et al 2002; Sullivan et al 2001). An individual forms pain beliefs, which are relatively stable across time, based on past experiences and cultural norms (Turner et al 2004; Werner et al 2005). There have been several tools designed to measure pain beliefs (e.g. Edwards et al 1992; Waddell et al 1993; Wallston et al 1978; Williams & Thorn 1989), any of which can be used to provide a reliable and valid assessment of the nature of a person’s beliefs about pain.

Pain beliefs are commonly divided into two subcategories, organic and psychological (Edwards et al 1992). Organic pain beliefs centre on the notion that pain indicates immediate or imminent physical harm (e.g. ‘Pain is the result of damage to the tissues of my body’). In contrast, psychological pain beliefs centre on the notion that pain is mediated by internal and external factors (e.g. ‘Thinking about pain makes it worse’). Pain beliefs have been associated uniquely and independently with disability and depression (Turner et al 2000).

There is more than two decades of evidence suggesting a relationship between organic pain beliefs and physical disability for patients with chronic pain (Jensen et al 1991; Sloan et al 2007), but the relationship with pain intensity has been minimal (Edwards et al 1992). In short, persons who have disabling chronic pain tend to strongly endorse organic pain beliefs and are less likely than people without chronic pain to endorse psychological pain beliefs (Edwards et al 1992; Walsh & Radcliffe 2002). Because pain beliefs are learned (Turner et al 2004; van Damme et al 2002; Werner et al 2005), they are also modifiable. Increasing a person’s belief that pain involves a significant psychological component tends to be associated with decreases in disability and, often, reports of reduced pain intensity (Bailey et al 2010; de Jong et al 2005; Jensen et al 2001; Walsh & Radcliffe 2002).

Mood

Depression symptoms have been associated with increased pain behaviour (e.g. guarding, bracing, rubbing, grimacing, sighing), reduced individual, social and occupation activity, as well as increased use of medical services (Arnow et al 2009; Asmundson et al 2008; Keefe et al 1986; Ratcliffe et al 2008; Smith et al 1998; Worz 2003). In chronic pain samples, prevalence rates of clinically significant depression vary based on the criteria used for assessment (Geisser et al 1997; Pincus & Williams 1999), but often exceed 28% (Morley et al 2002; Polatin et al 1993; Poole et al 2009; Worz 2003); in contrast, lifetime and 12-month community prevalence rates for depression are approximately 17% and 7%, respectively (Kessler et al 2005a,b). Persons with one pain site are nearly twice as likely to be depressed than persons with no pain, whereas persons with more than one pain site are nearly four times as likely to be depressed (Gureje et al 2008). In addition, the longer a person is in pain, or the more intense the pain, the more likely the person is to experience depressive symptoms (Krause et al 1994; Odegard et al 2007). Depressive symptoms do not necessarily impede treatment outcomes, however, and treating depression itself may provide reductions in disabling pain symptoms (Glombiewski et al 2010; Teh et al 2009).

Assessment of depression symptoms in persons with chronic pain should be ongoing, as there is evidence that pain is associated with fluctuations in mood over time (Krause et al 1994; Odegard et al 2007). In addition to structured clinical interviews (e.g. First et al 1996), there is a variety of standardized self-report tools that can measure ongoing depression symptoms (e.g. Beck et al 1988; Radloff 1977). Given the probability of low mood resulting from ongoing pain, the high rates of comorbidity with depression, and the associated personal and economic costs, ongoing depression symptom assessment should occur for all patients with disabling chronic pain.

Anxiety and fear

As with depression, persons with one pain site are nearly twice as likely to have clinically significant levels of anxiety compared to persons with no pain, whereas persons with more than one pain site are more than three times as likely to be anxious (Gureje et al 2008). Findings from community-dwelling adults in 17 countries (n = 85,088) indicate that those with back or neck pain are two to three times more likely to have current (i.e. past 12 months) panic disorder, agoraphobia or social anxiety disorder, and almost three times more likely to have generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Demyttenaere et al 2007). Data on lifetime prevalence show similar patterns. For example, community-dwelling women with fibromyalgia are four to five times more likely to have had a lifetime diagnosis of obsessive–compulsive disorder, PTSD or GAD than those without (Raphael et al 2006). In people seeking treatment for pain, some but not all studies indicate elevated prevalence of any current (25–29%) and lifetime (28%) anxiety disorder relative to the general population (18%) (Kessler et al 2005a,b), with specific elevations in the prevalence of current seasonal affective disorder, GAD, panic disorder and PTSD (for review, see Asmundson & Katz 2009).

Fear and anxiety related to pain are also pertinent issues. The constructs of pain-related anxiety and pain-related fear are often used interchangeably, but there is theory and evidence that suggests the two are distinct (Carleton & Asmundson 2009). Specifically, pain-related anxiety represents a response to anticipated future encounters with pain-related threats that drives avoidance behaviours; in contrast, pain-related fear represents a response to a current encounter with a pain-related threat that drives escape behaviours. There are differing opinions about whether pain-related fear is focused on painful sensations (Lethem et al 1983; Vlaeyen & Linton 2000), activities associated with those sensations (e.g. Waddell et al 1993) or painful reinjury (Kori et al 1990), or whether it is best subsumed by a fear of somatic sensations and changes (Asmundson et al 1999; Greenberg & Burns 2003). Despite the potential utility of clearly distinguishing between pain-related anxiety and pain-related fear, additional empirical study is required; as such, in the current text, pain-related anxiety will be used to refer to both constructs.

The structure of pain-related anxiety appears to be multidimensional (i.e. comprising cognitive, behavioural and physiological components; McCracken et al 1993) and continuous (i.e. occurring along a continuum ranging from low to high; Asmundson et al 2007). Accordingly, there is also evidence that pain-related anxiety is ubiquitous in the population (Carleton & Asmundson 2007; Carleton et al 2009). There have been several tools designed to measure pain-related anxiety (e.g. McCracken & Dhingra 2002; McNeil & Rainwater 1998; Melzack 1983) and ongoing assessment provides clinicians with information about a key cognitive component in the maintenance of disabling chronic pain.

Spirituality

Exploration of the relationship between religion, spirituality and chronic pain remains relatively novel. In a recent review, religious and spiritual beliefs were found to represent important components of the chronic pain experience (Rippentrop 2005; Unruh 2007). Many people with chronic pain report that religious and spiritual beliefs function as coping mechanisms that facilitate their continued activity (Büssing et al 2009), but the available evidence suggests that religious and spiritual beliefs do not directly impact pain intensity or pain interference (Rippentrop et al 2005). Research to date suggests most people with chronic pain reporting a religious affiliation neither feel abandoned nor punished as a function of their religious and spiritual beliefs, and that most report prayer to be an important coping strategy (Glover-Graf et al 2007). While additional investigation into the impact of religious and spiritual beliefs on the pain experience is warranted, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that religious and spiritual beliefs be considered as a component of comprehensive assessment. Several general and well-established measures of religious and spiritual beliefs are available (e.g. Cloninger et al 1994; Piedmont 1999) and more specific measures have been developed recently (e.g. Glover-Graf et al 2007).