Assessment of Wounds

Certain features of a wound are associated with a high risk of complications. The following must always be considered:

- Mechanism of injury: excessive force, high speed, retained glass, dangerous weapon

- Site of injury: trunk, perineum, neck, near a joint, over a neurovascular bundle

- Time of injury: wounds more than 6 h old are more likely to get infected

- Place of injury: field or garden injuries carry a greater risk of contamination with tetanus and gas-forming organisms.

Also Ask About

- Allergies to drugs including antibiotics

- Previous injuries: if the patient is a child, always consider child abuse (→ p. 353)

- Current medication, because some drugs may affect local treatment (e.g. anticoagulants)

Look For

- Site, extent and character of the wound

- Evidence of contamination, non-viable tissue or foreign bodies

- Involvement of deep structures. Assess distal neurovascular and tendon function and record the findings.

Bleeding is exacerbated by alcohol, anticoagulants, partial (rather than complete) tears of vessels and continued interference with wounds. If there is a potential for significant bleeding, intravenous (IV) access should be established.

Pain may be extreme with some small injuries. Less painful and more serious injuries may have been inflicted in the same incident and can easily be missed. Local anaesthetic may be needed before further investigation; sensory loss must be recorded first.

Anaesthesia for Wounds

All wounds must be explored and cleaned before closure is contemplated. This usually requires anaesthesia, as does the subsequent closure. A general anaesthetic will be required when the areas involved are multiple or large, or belong to children or anxious adults (→ Boxes 21.1 and 21.2).

Box 21.1 Local Infiltration

Box 21.1 Local Infiltration- Use lidocaine, always without adrenaline:

- 2% is suitable for nerve blocks; in a digital ring block this reduces the volume required and hence the risk of vascular compression

- 1% is appropriate for general use

- 0.5% should be used when large areas of tissue are involved and more than 10 mL anaesthetic are required

- 2% is suitable for nerve blocks; in a digital ring block this reduces the volume required and hence the risk of vascular compression

- Clean the wound edge with an antiseptic solution. If local anaesthetic is injected before the antiseptic has dried then the patient will be given a painful subcutaneous injection of both

- Always trim hair for at least 2 cm around the wound, before injecting local anaesthetic. The aim is to expose the wound fully and to prevent hair from interfering with the sutures. Scissors are usually adequate. A razor is sometimes necessary. Never shave the eyebrows

- Using a short 23 G needle, inject a small amount of lidocaine under the wound edge, either through the wound edge if the wound is fresh and socially clean, or through the skin if the wound is grossly contaminated or contused (safer but more painful)

- Once this small area is anaesthetised inject through it to raise a weal a little further on. Wait and then repeat. In this way, the patient feels only the first injection

Box 21.2 Ring Block

Box 21.2 Ring Block- Use only plain lidocaine (2% for an adult). Adrenaline added to the lidocaine may produce irreversible spasm of the digital arteries and loss of the finger

- Clean the base of the finger with antiseptic solution

- Insert a 23 G needle into the dorsolateral border of the base of the finger. The tip of the needle should end up near the bone on the palmar side of the finger. Aspirate and if blood is seen withdraw the needle and start again

- Inject no more than 2 mL of solution and much less in a child. The more fluid that is introduced the greater the risk of vascular damage. Repeat on the opposite side of the finger

- Wait for at least 5 min for full anaesthesia of the finger

- If digital artery spasm occurs stop the procedure. Massage the base of the finger where the anaesthetic has been injected and instruct the patient to move the finger vigorously. These manoeuvres should dissipate the fluid and release the spasm

Box 21.3 The Treatment of Severe Local Anaesthetic (LA) Agent Toxicity

Box 21.3 The Treatment of Severe Local Anaesthetic (LA) Agent Toxicity- Institute cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if required

- Attend to the ABCs

- Control convulsions with standard drugs

- Control cardiac dysrhythmias with standard therapy

- Treat cardiac arrest with lipid emulsion, continuing CPR throughout for up to an hour. (This is a relatively new approach. Intralipid 20% has been shown to reverse LA-induced cardiac arrest in animal models and in some human case reports. It has also been used successfully in life-threatening LA toxicity without cardiac arrest.) An intravenous bolus of 20% Intralipid 1.5 mL/kg is given over 1 min followed by an infusion of 0.25 mL/kg per min. The bolus injection can be repeated twice at 5-min intervals if an adequate circulation has not been restored and the rate of the infusion can be doubled.

Cleaning and Exploration of Wounds

Wound cleaning must be extensive and thorough. Particulate matter and contamination must be mechanically removed. This can be achieved by high-pressure irrigation or by scrubbing with a sterile nailbrush or toothbrush and an antiseptic solution. Hydrogen peroxide is not recommended nowadays. Dirt left in a wound may cause infection or be taken up by inflammatory cells to produce a permanent tattoo effect.

Exploration of a wound is essential to identify:

- the depth and extent of damage

- structures exposed or damaged

- foreign bodies.

An appreciation of the direction and force of the injuring agent will facilitate exploration.

Resection of Tissue:

- Use a scalpel to remove dead tissue and trim the edges of old wounds.

- Be very cautious in the face, scalp, foot and hand. Skin is at a premium here. Always ask for help with complex wounds in these areas.

Radiographs for Foreign Bodies

Foreign bodies are often surprisingly difficult to locate. The radiograph request card must indicate that a foreign body is being sought so that the radiographer can adjust the exposure accordingly. Glass is usually radio-opaque. Some thin metals (e.g. razor blades) can be surprisingly difficult to visualise on the film. Conversely, small fragments, obvious on a radiograph, can be very difficult to find and remove. Occasionally, less damage is done by leaving them in situ. This decision must be made after consultation with a senior colleague.

Closure of Wounds

- Primary: for most recent incised wounds

- Delayed primary: after 3–10 days, for crush injuries

- Secondary (i.e. by natural processes): when surgical closure is impossible and granulation and epithelialisation are encouraged.

Monofilament synthetic sutures are more difficult to handle than silk but are resistant to infection tracking up the thread and will give a better cosmetic result. Polyglycolic acid and catgut sutures evoke a pronounced tissue response as a necessary part of their autodestruction and are unsuitable for skin closure in an emergency department (ED). For most wounds 4/0 G sutures are used, with finer gauges for cosmetically sensitive areas. Absorbable sutures should be used to close subcutaneous spaces.

- Plan sutures strategically – do not just start at one end.

- Use interrupted sutures – not continuous or subcuticular because these cause increased risk of infection tracking along the suture.

Tissue glue, adhesive strips and skin staples are alternative methods of closure with several advantages:

- Less traumatic for children

- Sometimes less scarring but only if good apposition is achieved

- Sometimes cheaper

- Sometimes quicker to apply.

However, wounds closed with these methods still require thorough cleaning, possibly under local anaesthesia.

Skin Loss:

When closing defects in the skin, excessive tension should be avoided at all costs. If there is extensive skin loss or any loss on the face or hand, seek advice. Small skin defects elsewhere may be closed by undermining. This is achieved using a scalpel about 3 mm below the skin in the horizontal plane. A tissue plane may then be opened up using blunt scissors.

Aftercare of Wounds

Dressings may not be required (e.g. on the face) or may be of simple non-adherent type. Splintage should be minimal but may be necessary if a wound is over the extensor aspect of a joint.

Removal time for sutures varies with the site: 3–4 days on the face, up to 14 days in lower limbs or over joints, but usually about 7 days for most other parts of the body. Earlier replacement with adhesive strips may avoid permanent puncture-mark scars. Sutures may be removed in the GP clinic provided that adequate documentation accompanies the patient.

Postoperative analgesia depends on the patient’s needs. Efficacy, suitability of formulation and cost should all be considered.

Resuturing Wounds

Patients returning with wounds that have broken down should have a senior opinion. Such wounds must be cleaned and dressed until ready for resuture. Anything more than local infection requires oral antibiotics. Facial wounds need a specialised opinion and wounds in children may need reclosure under general anaesthetic. The possibility of a retained foreign body should always be considered.

Skin Grafts

These can be full thickness (Wolfe) or partial thickness (Thiersch); only the latter is generally used in EDs. The objective is to transplant the tops of the dermal papillae from the donor site, leaving the bases and skin appendages as a partial-thickness defect. This will heal by secondary intention. The donor skin must be applied directly to a clean, granulating wound. It will be nourished initially by direct tissue perfusion and then later by new capillary buds. The technique may not be suitable for patients on steroids with very thin, friable skin → Box 21.4.

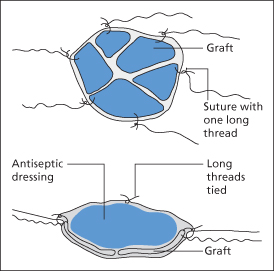

Box 21.4 Skin Grafting

Box 21.4 Skin GraftingReimplantation of Body Parts

Successful reimplantation of amputated body parts is possible using microsurgical techniques. Clean injuries without contamination or contusion have the best chances of success. Suitable structures for reimplantation include:

- the whole or part of a finger (with amputations proximal to the distal interphalangeal joint only)

- the penis

- ears

- large pieces of scalp

- hands, feet and more extensive parts of a limb.

Patients with these injuries should be discussed as soon as possible with the nearest plastic surgery unit. The amputated part should be wrapped in saline-soaked gauze and then put in a plastic bag in a container full of crushed ice. The body tissue must not come into direct contact with the ice as tissue necrosis may occur.

Prevention of Wound Infection

This is achieved in most cases by:

- cleaning the wound

- excising necrotic tissue

- closing the wound as appropriate

- dressing the wound carefully

- using antibiotics when indicated (→ Box 21.5)

- anticipating the presence of spore-forming organisms (→ later).

Box 21.5 Indications for Antibiotics in Wound Care

Box 21.5 Indications for Antibiotics in Wound Care- are already showing signs of infection when seen

- are more than 12 h old and in need of primary closure

- have a definite history of contamination with problem organisms (e.g. human and cat bites)

- are possibly contaminated with deep areas that are not amenable to cleaning (e.g. some puncture wounds)

- have exposed or damaged deep structures (e.g. bone in compound fractures, tendon or nerve)

Patient compliance in aftercare is essential.

The most common wound contaminants are bacteria from the skin, so flucloxacillin or clarithromycin is adequate cover. In bites, however, a wider spectrum of organisms is involved and so co-amoxiclav or clarithromycin should be prescribed.

Spore-forming organisms are more likely to contaminate wounds incurred on sports fields or in gardens, and also injuries of the lower limb. They will flourish in areas of hypoxia, e.g. deep, penetrating and contused wounds. Primary prevention involves scrubbing all wounds under effective anaesthesia and surgically removing all necrotic tissue. Contused wounds should not be closed. All foreign material must be removed.

Gas gangrene can be prevented if wounds are managed as outlined above. Long-acting penicillins are no substitute for adequate wound toilet.

Prevention of Tetanus

Table 21.1 Tetanus prophylaxis

| Patient immunisation status | Tetanus-prone wound | Other wound |

| Has had five or more doses of vaccine during lifetime | Nothing required (HTIg if very high risk of contamination) | Nothing required |

| Has had complete course of three doses or booster dose within the last 10 years | Nothing required (HTIg if very high risk of contamination) | Nothing required |

| Has had three-dose course of vaccine or single booster >10 years ago | Booster dose + consider HTIg if wound contaminated | Booster dose |

| Has never had complete course of vaccine or immune status unknown | Complete course of vaccine + HTIg if wound contaminated | Complete course of vaccine |

HTIg, human tetanus immunoglobulin.

There are still several cases of tetanus in the UK every year, although prophylaxis against tetanus is cheap and safe. Infection is caused by contamination of a wound with the spores of the bacillus Clostridium tetani. Days or even weeks after infection, local multiplication of the organism occurs with release of its neurotoxin → p. 233. Until recently, most cases of tetanus in the UK were in people aged >65 years who had not been previously immunised. In the last few years, tetanus has also been seen in young adults who abuse IV drugs. Even the most trivial of wounds can introduce tetanus into the body but some wounds carry a particularly high risk. For factors that identify tetanus-prone wounds → Box 21.6.

Box 21.6 Tetanus-Prone Wounds

Box 21.6 Tetanus-Prone Wounds- are >6 h old at presentation

- are deeper than they are long (stab or puncture wounds)

- contain devitalised tissue

- are possibly contaminated with soil or manure

- show clinical evidence of sepsis

With diphtheria on the increase in eastern Europe, single antigen tetanus vaccine (T) has been replaced by the combined tetanus and low-dose diphtheria vaccine for adults and adolescents (Td) for all routine uses. Td replaced single tetanus as the standard booster for UK school leavers in 1994. For both diphtheria and tetanus, a total of five doses of vaccine are considered to give life-long immunity. These may have been given either as the primary three-dose course in childhood followed by school entry and school-leaving doses, or as a primary course at any time followed by a booster dose 10 years later and a second booster 10 years after that. Polio vaccine is usually also included in the booster doses.

Unscheduled booster doses are therefore indicated only for the following indications:

Tetanus toxoid vaccine confers active immunity. It stimulates the production of antibodies, which may take several weeks to reach a peak. Therefore, in the case of contaminated wounds, patients receiving Td vaccine in the first two categories above should also be given passive immunisation with human tetanus immunoglobulin (HTIg) → later. The two injections should be given into separate areas. Patients with impaired immunity may not respond to active immunisation and may therefore also need HTIg.

Patients with doubtful or unknown immune status to tetanus and diphtheria require a full primary course of Td vaccine (three doses at 1-month intervals). Notification should be sent to the patient’s GP to this effect. Two further booster doses at 10-year intervals will also be required to confer life-long immunity.

Td vaccine is given by deep subcutaneous or intramuscular (IM) injection. Local reactions such as pain, redness and swelling around the injection site may occur and persist for several days. Acute allergic reactions (anaphylaxis or urticaria) are uncommon; peripheral neuropathy is a rare but recognised side effect. Vague post-immunisation symptoms such as headache, pyrexia, lethargy, malaise and myalgia may also occur occasionally. Persistent nodules at the injection site may arise after shallow injections.

The contraindications to Td vaccine are as follows:

HIV-positive status is not a contraindication to immunisation.

Human Tetanus Immunoglobulin

Human tetanus immunoglobulin (HTIg) gives passive immunity. It is a preparation of human antibodies, which is not associated with significant side effects or allergy, unlike the previously used horse serum. The dose is 250 IU by deep IM injection. This may be increased to 500 IU if more than 24 h have elapsed or if there is a risk of heavy contamination or after large burns.

Tetanus and Diphtheria Immunisation for Children

The administration of an unscheduled tetanus and diphtheria immunisation to a child may cause great difficulty with the correct timing of other immunisations. For this reason, concurrent administration of the other recommended immunisations for that age group or referral to the child’s health visitor is usually the better practice.

Wound Botulism

This related clostridial infection has recently re-emerged in the UK.

SPECIFIC TYPES OF WOUNDS

Abrasions

Motorcyclists and children may present with dirty abrasions.

TX

The basic care is as for any wound. However, the ingrained dirt must be removed to prevent infection and to avoid the development of a permanent ‘tattoo’. Scrubbing with a swab or a small brush may be necessary. Analgesia for this purpose can be obtained by:

- application of local anaesthetic gel

- infiltration of local anaesthetic

- general anaesthesia.

Crush Wounds

Where there is an element of crush or bursting in the mechanism of injury there is widespread damage to tissues. Extracellular fluid accumulates and the tissues continue to swell for 24–48 h.

TX

The wound should be cleaned, explored and then dressed.