Extrinsic lesion

Intrinsic lesion

Obstruction of normal bowel

Adhesions

Intussusception

Gallstones

Hernia

Congenital malformation

Feces or meconium

Volvulus

Neoplasms

Bezoar

Extrinsic neoplasms

Intussuception

Gallstones

Intra-abdominal abscesses

Congenital malformation

Feces or meconium

Aneurism

Neoplasms

Bezoar

Hematomas

Inflammatory strictures

Ascaris infection

Endometriosis

Crohn’s disease

Barium

Adhesions

The most common cause of small bowel obstruction is adhesions, accounting for 60% of all cases. The risk of developing small bowel obstruction secondary to adhesions postoperatively has been estimated to be 9% in the first postoperative year and then increases to 19% by 4 years postoperatively and 35% by 10 years postoperatively [5]. Thus, informed consent for any abdominal operation should include the risk of developing adhesions and the potential need for further surgery in the future. It is difficult to predict when the patient will develop small bowel obstruction. In a study of 446,331 abdominal operations Barmparas et al. showed a strong and independent association between surgical procedure type utilized and the proportion of patients with adhesion-induced small bowel obstruction (Table 24.2) [6]. The identification of surgical procedure type as an independent risk factor for small bowel obstruction may have a predictive value for stratifying patients. A recent report by Angenete et al. suggests that factors such as age, previous abdominal surgery and comorbidity are important predictors of risks of hospitalization for small bowel obstruction or surgery for small bowel obstruction [7]. The incidence of small bowel obstruction among patients who have had bariatric surgery, including gastric bypass, was 3.2%. The estimated overall incidence of small bowel obstruction among patients who underwent abdominal trauma surgery operations was 4.6% [6].

Table 24.2

Association between surgical type or surgical procedure and the incidence of adhesion-induced small bowel obstruction

Procedure type/group | Incidence of SBO |

|---|---|

Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis | 19.3% (1,018/5,268) |

Open colectomy | 9.5% (11,491/121,085) |

Gynecological procedures | 11.1% (4,297/38,752) |

•Open anexal surgery •After cesarean section | •23.9% •0.1% |

Cholecystectomy | |

•Open •Laparoscopy | •7.1% •0.2% |

Hysterectomy | |

•Total hysterectomy •Laparoscopy | •15.5% •0.0% |

Adnexal operations | |

•Open •Laparoscopy | •23.9% •0.0% |

Appendectomy | |

•Open •Laparoscopy | •1.4% •1.3% |

Neoplasm

Neoplasms are the second most common cause of small bowel obstruction, comprising 20% of the cases [8]. If an adult patient presents with a small bowel obstruction and has a virgin abdomen (meaning the patient has not had any previous abdominal procedures) the etiology of a neoplasm as the source of obstruction must be entertained. Other causes could include inflammatory bowel disease, gallstones, ileus, or intussusceptions. More common origins of neoplasms include colorectal carcinoma, and ovarian carcinoma in women. Extrinsic compression, adhesions, and carcinomatosis are often seen as the etiology of small bowel obstruction in these cases.

Hernias

Hernias are the third leading cause of small bowel obstruction, comprising 10% of cases [8]. When examining a patient with a small bowel obstruction, the surgeon must be cognizant of the potential hernia etiologies. A meticulous examination of the groin, femoral region, parastomal region, and old surgical scar sites is warranted. In thin females an obturator hernia can be the cause of small bowel obstruction. One must have a high index of suspicion and this type of hernia can be identified with abdominal CT.

Other Extrinsic Causes

Malrotation and congenital or acquired hernias are less common causes of small bowel obstruction. Malrotation can present in both the pediatric and adult populations. Congenital hernias include transmesenteric, transomental, and paraduodenal hernias [9]. Acquired hernias develop after a resection of bowel where there exists a mesenteric defect. Bowel can herniate through this defect and cause a small bowel obstruction. The idea has been proposed that with the increase in laparoscopic procedures, defects are not closed as often, and the incidence of internal hernia increases. Experience with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y-gastric bypass (LRYGB) has attempted to answer these questions about small bowel obstruction and internal hernia incidence. However, the literature is mixed. What is important for the acute care surgeon to realize is that you will be seeing these patients come into the emergency department with small bowel obstruction secondary to internal hernias. There are three potential spaces: Petersen’s space, the mesocolic space, and the mesomesenteric space. The Petersen’s hernia occurs in a potential space posterior to the gastrojejunostomy (for example: See Fig. 24.1). Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is done with an antecolic or retrocolic anastomosis. If a retrocolic anastomosis is performed, a defect in the mesocolon is necessary and there exists a potential space. The mesomesenteric potential space at the jejunojejunostomy is another area where an internal hernia can develop. Intra-abdominal abscesses may cause bowel obstruction via extrinsic causes by kinking the bowel as it adheres to the abscess cavity or even within it.

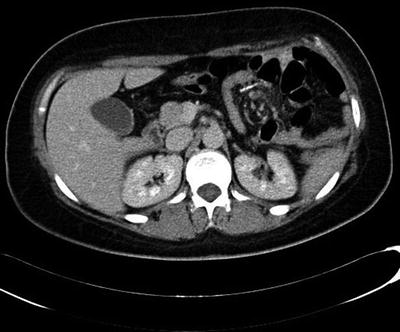

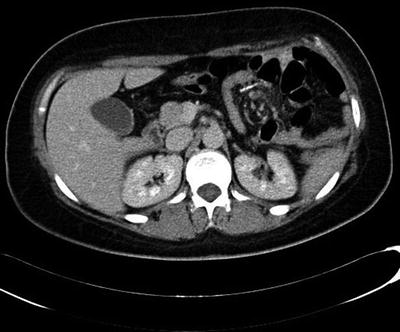

Fig. 24.1

Axial CT demonstrating Petersen’s hernia with swirling of the mesentery evident in this image. Small bowel is seen herniating above the level of the stomach. There is a potential space posterior to the gastrojejunostomy where this herniation occurs. Radiopaedia.org (http://radipaedia.org/cases/peterserns-hernia), case ID: 14053

Intrinsic Causes

Intrinsic obstructions are due to such causes as aganglionic megacolon, primary tumors, Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, and intussusceptions. Crohn’s disease causes strictures responsible for small bowel obstruction. Multiple resections of small bowel in patients with Crohn’s can eventually lead to an endpoint of short bowel syndrome. Strictures can also be caused by radiation and ischemia. Irradiated bowel is very friable and the risks of enterotomies and subsequent fistula development are high. Intussusception is commonly identified with CT scans; however, the clinical significance can be questionable. However, when the intussusception is the lead point for small bowel obstruction in an adult, malignancy should be ruled out. In trauma, small bowel hematomas can cause bowel obstruction. The duodenum is particularly susceptible because a portion is fixed in the retroperitoneum. Most duodenal hematomas resolve without the need for operative interventions.

Intraluminal obstructions are caused by impacted feces, gallstones, enterolith, bezoar, tumors, large polyps, and ingested foreign bodies. Small bowel tumors are rare but an important etiology of small bowel obstruction. They present with vague abdominal symptoms and ultimately cause small bowel obstrution. These include small bowel adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumors, and lymphoma.

There is clinically significant morbidity associated with small bowel obstruction, although the mortality rate for patients with mechanical obstruction has been dramatically reduced in recent years. The observed improvements in mortality rate have been attributed to early diagnosis, appropriate strategic use of isotonic fluid resuscitation, gastric tube decompression, antibiotics, and surgery.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

A well-conducted patient history is essential for formulating an initial working diagnosis for small bowel obstruction. Informative patient symptoms include the following: abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, obstipation, fever, tachycardia, or diarrhea secondary to increased peristalsis. Pain paroxysms at 4–5 min intervals are associated more frequently with distal obstructions whereas nausea and vomiting are sometimes more common in patients with more proximal obstructions. The past surgical history should be detailed. As shown in Table 24.2, there is strong association between surgical procedure type/group and the risk of developing a small bowel obstruction. On physical examination, a patient with a small bowel obstruction can present with tachycardia, fever, distended abdomen, and evidence of previous surgical scars. The time course of development of a small bowel obstruction is often reflected in an early rise in hyperactive bowel sounds (e.g., borborygmi) followed by significant reduction or complete cessation of bowel sounds. In refining the diagnosis for small bowel obstruction, it is important to exclude specific explanatory etiologies such as incarcerated hernias in the groin, the femoral triangle, and the obturator triangle. Extraluminal masses need to be excluded and distal colon obstruction can sometimes be excluded by rectal examination. Patients with positive rectal exam results should prompt a test for occult blood to assess for the possibility of a malignancy, intussusception, or infarction. The abdominal exam is extremely important in the diagnosis of a small bowel obstruction. Patients with suspect small bowel obstruction often have abdominal distension and tenderness. The tenderness may be localized but more often is diffuse. The reason the physical exam is so important is because patients with small bowel obstruction either resolve or progress and the intestines can become ischemic if not taken to the operating room in a timely manner. A worsening physical exam may be a signal of bowel necrosis. Consequently, the patient may begin to exhibit signs of peritonitis, diffuse tenderness, rebound, and guarding. Laboratory data should be obtained to include complete blood count (CBC) and basic metabolic panel at a minimum. Other tests such as liver function tests, arterial blood gas (for base deficit) and lactate may be helpful but are not absolutely essential. An increasing white blood cell (WBC) count, increasing base deficit or lactate, intravascular volume depletion, and low urine output are measures of a patient that is getting worse clinically (for treatment algorithm see Fig. 24.2).