Sinusitis and Rhinitis

Hagop M. Afarian

Upper respiratory complaints, including sinusitis, are among the most common disorders encountered by the emergency physician. It is estimated that 14% of the US population, approximately 31 million people, are treated annually for diseases of the paranasal sinuses, costing approximately 5.8 billion dollars each year (1,2). Sinus disease is usually a harmless inconvenience; however, it occasionally presents as a fulminant, life-threatening entity in the ED.

Sinusitis is an inflammatory disease of the paranasal sinuses resulting from infectious, allergic, or autoimmune processes (3). Rhinitis strictly means inflammation of the nasal mucous membranes. Rhinitis may be caused by allergic (most common), nonallergic, infectious, hormonal, occupational, and other factors (4). This chapter will focus on rhinitis as part of a broader infectious disease spectrum. Rhinosinusitis has been proposed as a more precise definition, as inflammation frequently involves the nasal passages, and sinusitis without rhinitis is rare (5).

The human sinuses are composed of four paired, sterile cavities lined with ciliated, columnar epithelium. Maxillary and ethmoid sinuses are present at birth. Frontal and sphenoid sinuses develop in the 7th and 10th year of life, respectively (6). Individual sinus anatomy is highly variable, with frontal sinuses absent in 2% to 5% of the population (7). The posterior ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses empty into the superior meatus. The frontal, anterior ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses empty into the ostiomeatal complex within the middle meatus. Obstruction of the ostiomeatal complex (OMC) caused by inflammation, anatomic abnormality, or other pathology is the critical event in the development of acute sinusitis (6). Maxillary sinusitis is most common, followed by ethmoid, frontal, and sphenoid (1).

A practice guideline published in the 2007 Journal of Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery classified sinusitis into acute (<4 weeks), subacute (4 to 12 weeks), chronic (>12 weeks) with or without acute exacerbations, and recurrent acute (having four episodes of sinusitis within 1 year with complete resolution of symptoms between each episode) (2).

The exact incidence and prevalence of sinusitis is difficult to determine because of a lack of rigid criteria defining sinus disease. Women are affected approximately twice as often as men (8). An estimated 0.5% to 2% of upper respiratory infections (URIs) in adults and 5% of URIs in children are complicated by acute bacterial sinusitis (8). Furthermore, up to 16% of Americans suffer from chronic sinusitis (2,9).

Most cases of sinusitis follow a viral URI. Viruses injure the sinus epithelium, resulting in ciliary dysfunction and an inflammatory cascade. Mucostasis and a damaged epithelium make the sinuses susceptible to secondary bacterial invasion. Inflammation results in occlusion of the OMC, obstructing sinus drainage and creating a hypoxic, hypercarbic, acidic environment with negative pressure, promoting bacterial growth (10).

Other factors contribute to the development of sinusitis. Five percent to 10% of acute maxillary sinusitis occurs because of contiguous spread of dental infection (9). Ciliary motility disorders, both congenital (Kartagener syndrome) and acquired, predispose to sinusitis. Inflammatory changes and anatomic abnormalities (polyps, adenoids, tumors) can result in OMC occlusion. Nasal foreign bodies also result in OMC obstruction, leading to sinusitis; 95% of nasally intubated patients develop sinusitis (9). Immunocompromised patients are more susceptible to the development of sinusitis and are more likely to have severe disease (9).

Infectious sinusitis can be of viral, bacterial, or fungal origin. Viral rhinosinusitis is 20 to 200 times more common than bacterial sinusitis (11). Over 200 viruses have been implicated, with subtypes of rhinovirus, parainfluenza, and influenza virus being the most common (12). Streptococcus pneumoniae (30% to 40%), nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (30% to 40%), Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, other streptococcal species, and anaerobes of dental origin compose the primary pathogens in acute bacterial sinusitis (8). Viral infections predominate in the first 10 days followed by a predominance of aerobic bacteria for up to 3 months and then anaerobic bacteria thereafter (10). Pseudomonas sp is an important pathogen in patients with cystic fibrosis and HIV and those with nasal tubes. Fungal sinusitis may present as an acute fulminant or a chronic indolent process. Mucoraceae species including Rhizopus sp, Mucor sp, and Absida sp cause necrotizing invasive disease, most often in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis (13). Aspergillus sp are becoming a more common pathogen, manifesting in one of the three chronic forms in immunocompetent adults: indolent invasive, mycetoma (“fungus ball”), and allergic fungal sinusitis, the most frequent form of fungal sinusitis in the United States (14).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical presentation of acute sinusitis is highly variable, but usually includes purulent nasal discharge, congestion, facial pressure, dental pain, fever, headache, cough, fatigue, halitosis, or a diminished sense of smell. Many of the symptoms are indistinguishable from those of a viral URI; thus duration of symptoms becomes critical in diagnosis. A patient with cold symptoms not resolving after 7 to 10 days has a higher likelihood of acute bacterial sinusitis (11).

Systemic toxicity, mental status changes, severe headache, and fever are signs and symptoms indicative of a more serious sinus disease and its complications (7). Periorbital cellulitis is the most common complication of sinusitis, usually originating from the ethmoid sinuses (15), and must be differentiated from orbital cellulitis (see Chapter 60). Intracranial complications of sinusitis include meningitis, osteomyelitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and intracranial abscesses (epidural, subdural, and intracerebral). Fifteen percent of meningitis cases may be of paranasal sinus origin (7). Extension of acute frontal sinusitis with suppurative inflammation of cortical bone results in the Pott puffy tumor, a condition requiring aggressive surgical and antimicrobial therapy (15). Cavernous sinus thrombosis presents with periorbital edema, exophthalmos, papilledema, and cranial nerve III, IV, and VI palsies. Intracranial abscesses will usually present with fever and acute neurologic signs, and 33% of patients develop long-term morbidity, including blindness, hemiparesis, seizure disorders, and cognitive impairment (7).

Special consideration must be given to the immunocompromised host with sinus complaints, as invasive fungal sinusitis is much more common in this population. Patients are typically toxic and may present with moldy smelling, thick, brown or black nasal discharge. The nasal mucosa may become gray and eventually necrotic from fungal–vascular invasion. Perforation of the palate, nasal septum, or cribriform plate may be apparent (14). The invasive organisms cause ischemic necrosis of the bone and mucosa with hematogenous invasion of the orbit, skin, and brain. Progression to coma and death can occur within hours. Interestingly, acute fungal sinusitis is relatively rare in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients, presenting as a late-stage phenomenon when CD4 counts drop to <50/mm3 (14). Aspergillus is the most common fungal pathogen in this group.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis for sinusitis is broad, as the signs and symptoms of sinus disease are neither sensitive nor specific. Viral URI, nasal polyps, cocaine abuse, allergic rhinitis, and vasomotor rhinitis all may present with symptoms of nasal discharge and congestion. Cerebral spinal fluid rhinorrhea should be considered in a patient with a history of head trauma. Persistent unilateral nasal discharge with epistaxis is concerning for neoplasm or nasal foreign body (1). Tension, cluster, and migraine headaches and dental disease are alternative diagnoses in the patient whose sinus disease manifests as cephalgia or facial pain.

ED EVALUATION

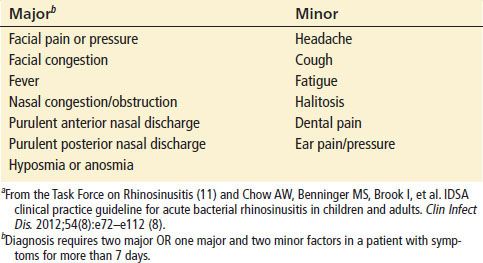

Acute sinusitis is a diagnosis based primarily on clinical history and physical findings (Table 67.1). Unfortunately, physical examination findings are not specific for acute sinusitis (12). Findings may include mucosal hyperemia, purulent rhinorrhea, nasal airway congestion, crusting of the anterior nares, and facial pain. However, palpable facial tenderness is a poor indicator of underlying sinus infection, and “purulent” discharge is not a reliable indicator of bacterial sinusitis (8). Transillumination has poor correlation with the presence of fluid, poor intraobserver consistency, and poor specificity. Thus, transillumination is of little use in the diagnosis of acute sinus disease (12).

TABLE 67.1

Major and Minor Factors for Diagnosis of Acute Sinusitisa