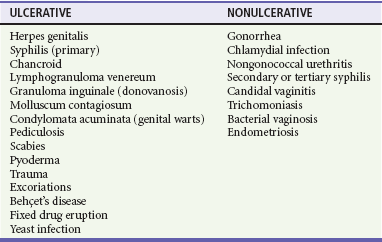

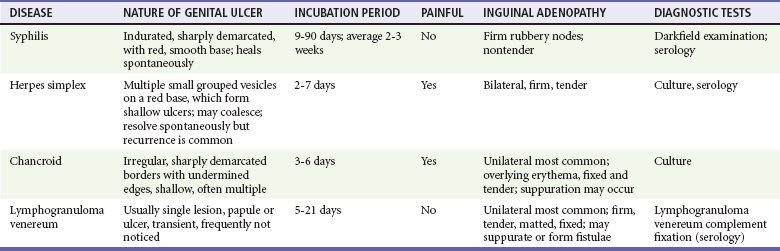

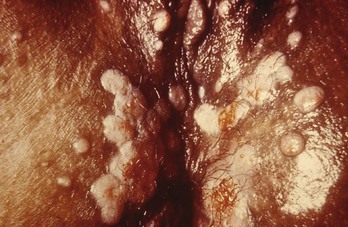

Chapter 98 More than 300 million new cases of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are diagnosed worldwide each year. In the United States, nearly 20 million new cases of STDs are diagnosed annually, and patients with these infections frequently come to the emergency department (ED) for care.1 Because EDs often are used as a source of primary health care, their role in screening and treating STDs has been debated. One major area of difficulty in use of EDs for this purpose is that many test results are not available during the ED visit. Treatment decisions are therefore made presumptively, inevitably leading to both overtreatment and undertreatment for STDs. As evidence supporting this concern, one third of patients who test positive for STDs in the ED are not treated during the initial visit, and a majority of untreated patients do not return for subsequent treatment.1 As a result, emergency providers should weigh the cost of overtreatment against the risk of untreated disease. Because these diseases pose a significant public health risk, it is recommended that patients be treated presumptively in the ED unless good follow-up for test results can be ensured. In addition, to help contain these diseases, many states allow expedited partner therapy (EPT) or patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT), allowing physicians to prescribe treatment not only for the patients being treated but also for their sexual partners. (Information on EPT and PDPT and the states that allow it is available on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] website [www.cdc.gov]). The STDs can be divided into two broad categories: those that manifest with genital lesions, with or without adenopathy, and those that are nonulcerative, which most frequently cause genital discharge (Table 98-1). STDs are a well-recognized cause of genital lesions. It is important to note, however, that patients with a “sore” on or near the genitalia or anus may be using this term to refer to genital warts, scabies, premalignant lesions, or other conditions. If an STD is the cause, certain components of the history and physical examination can provide crucial information to help narrow the diagnosis to a specific infection (Table 98-2). The history and physical examination should focus on the characteristics of the lesion or lesions, the presence or absence of adenopathy, and the presence or absence of systemic symptoms. With regard to the lesions, it is important to determine whether they are single or multiple, painful or painless, indurated or soft; whether they have irregular or regular borders; and how they began (e.g., as a vesicle or papule). If the patient has lymphadenopathy, examination will determine if they are unilateral or bilateral and whether the nodes are painful or fluctuant. In the United States, genital herpes is the most common cause of ulcerative STDs, with 50 million people infected with the virus and 200,000 to 300,000 new symptomatic cases annually.2 One in five sexually active adults is infected with the virus, many of whom are asymptomatic. Most commonly caused by HSV type 2, genital herpes also can be caused by HSV-1. In pregnant patients, herpes can cause a devastating congenital infection, although the incidence of such infections has decreased. In addition, HSV infection plays a major role in the transmission of HIV as herpetic lesions increase the risk of both acquisition and transmission of HIV. Clinically, genital herpes manifests as either primary herpes infection or recurrence. In primary infections the degree of illness depends on whether the patient has preexisting circulating antibodies to either HSV-1 or HSV-2; in cases of initial genital infection, those with antibodies tend to have a milder syndrome than those without. In cases of primary infection in patients without antibodies, symptoms develop after a 2- to 7-day incubation period. The syndrome begins with genital lesions that may start as vesicles and rapidly become painful, shallow, multiple, and grouped ulcers (Fig. 98-1). In women, these lesions may coalesce into large ulcerations on the perineum (Fig. 98-2). Systemic symptoms may include low-grade fever, myalgias, headache, and fatigue. Adenopathy typically develops during the second or third week of the illness and is bilateral, mildly tender, and nonfluctuant. The local symptoms peak at approximately 8 to 10 days, and it takes 2 to 4 weeks for the lesions to completely heal. Viral shedding can last as long as 3 weeks. In some cases, sacral radiculopathy may develop, with urinary retention, constipation, and sensory changes in the perineal region. Aseptic meningitis and transverse myelitis are relatively uncommon complications. In contradistinction to patients without antibodies, patients acquiring an initial herpes genital infection who have circulating antibodies to the herpesvirus have a milder course, often developing only the genital lesions. As the symptoms of primary infection recede, the virus settles in the spinal cord ganglia and becomes latent, residing there for the lifetime of the patient. Symptomatic recurrences are the rule, occurring in 60 to 90% of patients. In contrast to the prolonged syndrome and systemic symptoms of primary infection, recurrences are much shorter in duration and tend to cause only mild local symptoms. Many patients will be warned of an impending recurrence by a prodrome, usually characterized by paresthesias, burning, or itching at the site of the subsequent lesions. Although it is known that viral shedding can occur during a recurrence, data suggest that in patients infected with HSV-2, shedding occurs during asymptomatic periods as well.3 Although viral culture of a lesion has traditionally been the “gold standard” diagnostic modality, this test has a low sensitivity, takes 3 to 10 days to complete, and has false-negative results ranging from 5 to 20%. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for HSV DNA is more sensitive and is now the preferred method for making the diagnosis.3 Recently available serologic testing is type-specific, but patients with newly acquired viral infection may take up to 6 weeks to show positive antibodies.3 This test is most useful in patients with symptoms consistent with herpes but with negative results on culture or antigen testing. In the patient with a new presentation, PCR testing for HSV DNA is the recommended diagnostic test. Although genital herpes is incurable and outbreaks are self-limited, treatment decreases the duration of symptoms in patients with primary infection, can shorten or abort recurrences, and decreases the amount and duration of viral shedding and therefore potential infectivity. In patients with frequent recurrences, suppressive therapy can decrease the number of these episodes by up to 80%.4 The mainstay of treatment is therapy with one of the antiviral drugs acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir5 (Table 98-3). None of these agents can eliminate the virus, but their use can control symptoms, at least while the drug is being taken. Acyclovir has been shown to be safe for up to 6 years’ continuous use as a suppressive agent; the other antivirals have been proven safe for 1 year.6 Table 98-3 Treatment Guidelines for Sexually Transmitted Diseases IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; PO, orally. *Because of resistance, quinolones are no longer recommended for the treatment of gonorrhea. Also, recent increases in cephalosporin resistance led to the removal of the previously recommended cefixime as treatment for uncomplicated gonorrhea. The organism is fragile and does not survive on dry surfaces. Transmission occurs during exposure of moist skin to an infected area. Although transmission usually involves the genitalia, inoculation can occur virtually anywhere on the body. The incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States hovers between 7000 and 10,000 cases per year.7 If untreated, syphilis typically progresses through several stages, as follows. 1. Primary. The primary lesion, called a chancre, occurs after an incubation period that varies from 9 to 90 days, averaging 2 to 4 weeks. This lesion occurs at the site of inoculation and begins as a papule that then ulcerates. Typically the chancre is solitary and painless and has a smooth, slightly raised edge, with sharply defined borders and a clean base (Fig. 98-3); occasionally patients have more than one lesion (Fig. 98-4). Without treatment the chancre lasts for 2 to 6 weeks and resolves spontaneously, and the disease then progresses to the secondary stage. Adenopathy is not a predominant feature of primary syphilis. If the chancre is on the genitalia, bilateral, painless, nonfluctuant, and slightly enlarged inguinal adenopathy may develop several days after appearance of the primary chancre. 2. Secondary. Manifestations of the secondary stage of syphilis begin 5 to 8 weeks after resolution of signs and symptoms of the primary stage. The most common manifestation is a total body rash (Fig. 98-5). This rash begins on the trunk as a fine macular rash, which then spreads outward to the arms and legs and may involve the palms and soles (Fig. 98-6). As it progresses, it becomes papulosquamous and may appear slightly annular, often resembling the rash of pityriasis rosea. Mucous patches can be seen on the tongue, which are the oral manifestations of the skin rash. Condylomata lata (Fig. 98-7) can also develop; these lesions are broad-based papules with flat moist tops, occurring in the perineal region, and may involve the anus, the skin between the buttocks, and the labia. Constitutional signs and symptoms are common during this stage, including fatigue, low-grade fever, malaise, headache, arthralgias, and generalized lymphadenopathy. Adenopathy may occur virtually anywhere in the body, including epitrochlear node involvement. The nodes are discrete, nontender, and rubbery. As with the primary stage, the manifestations of secondary syphilis will resolve spontaneously if the condition goes untreated, and the infection then enters the latent or tertiary stage. 3. Latent. After resolution of the clinical manifestations of secondary syphilis, patients enter the latent phase, which is defined as seroreactivity for syphilis without evidence of disease. As there are no clinical signs and symptoms during this stage, laboratory testing is the only means to identify infected persons. Latent syphilis is divided into two categories: early latent syphilis, acquired within the preceding year, and late latent syphilis, the designation for all other cases of latent syphilis or for latent syphilis of unknown duration. 4. Tertiary. In the immunocompetent individual, signs and symptoms of tertiary syphilis may appear after a latent period of at least 3 to 4 years. This stage predominantly involves the cardiovascular and nervous systems. Presenting conditions may include a thoracic aortic aneurysm, meningitis, peripheral neuropathy (tabes dorsalis), or gummatous lesions of the mucous membranes. Although common in the preantibiotic era, tertiary syphilis is now uncommon in the United States. The only rapid means of diagnosing syphilis is the darkfield examination. This method involves viewing scrapings or fluid from primary or secondary syphilis lesions under a darkfield microscope to identify the spirochete. Unfortunately, the sensitivity of darkfield microscopy is approximately 80%, and many hospitals and clinics do not have this technique routinely available.5 Serologic testing is the current standard for diagnosing secondary, latent, and tertiary syphilis. In primary syphilis, one-time testing is less reliable, and follow-up testing may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. There are two types of serologic tests: nontreponemal—the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests—and treponemal—microhemagglutination assay for T. pallidum (MHA-TP) and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test. Both types of tests are necessary for definitive diagnosis, although the nontreponemal test is used for screening, with treponemal testing used for confirmation. Nontreponemal tests measure nonspecific antibodies in serum from patients with syphilis, and the titers tend to vary with the stage and activity of disease. These tests involve quantitative measurement of antibody and become positive approximately 2 weeks after the primary chancre appears. Titers are used to follow response to treatment. Because these tests are nonspecific for the treponeme and false-positive results can occur, positive test results should be confirmed with the more specific treponemal tests. Treponemal tests measure antibodies specific to the spirochete T. pallidum. These tests are more expensive and difficult to perform than the nonspecific tests, and because their titers do not predictably vary with treatment, the main value of these tests is in confirming positive findings on nontreponemal tests.5 A one-time dose of the long-acting formulation of penicillin G benzathine, 2.4 million units intramuscularly (IM), is the regimen of choice for treating primary and secondary syphilis5 (see Table 98-3 for treatment of latent and tertiary syphilis). It is crucial that the long-acting form of penicillin G benzathine be used; the half-life of an alternative preparation comprising both penicillin G benzathine and penicillin G procaine (i.e., Bicillin C-R) is too short, which has resulted in treatment failures.5 Sexual partners need to be evaluated; partners within the last 90 days should be tested but treated presumptively, and partners from more than 90 days before diagnosis should be evaluated and treated if indicated. Because syphilis increases the risk of acquisition of HIV, all patients should be referred for HIV testing. For response to treatment to be ensured, patients should be reexamined clinically and serologically 6 and 12 months after treatment. Successful treatment is confirmed by either a nonreactive nontreponemal test or a fourfold or greater decrease in titers after 6 months. Because syphilis is a reportable disease, patients with positive test results should be reported to the public health department. Because congenital syphilis can be devastating, pregnant patients with syphilis pose a unique and significant concern. Parenteral penicillin G is the only agent with documented efficacy in these instances. Therefore in pregnant women with a reported penicillin allergy who have syphilis at any stage, treatment with penicillin is still recommended after desensitization.5

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Perspective

Disorders Characterized by Genital Lesions with or Without Adenopathy

Herpes

Diagnosis

Treatment

DISEASE

RECOMMENDED TREATMENT REGIMEN

ALTERNATIVE(S)

Chlamydial infection

Azithromycin 1 g PO × 1 or

Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid × 7 days

Erythromycin base 500 mg PO qid × 7 days or

Erythromycin ethylsuccinate 800 mg PO qid × 7 days or

Ofloxacin 300 mg PO bid × 7 days or

Levofloxacin 500 mg PO qd × 7 days

Gonorrhea,* uncomplicated urethral, cervical, or rectal infection

Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM × 1

plus

Azithromycin 1 g PO once

May substitute azithromycin with doxycycline 100 mg PO daily for 7 days

Gonorrhea,* pharyngeal

Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM × 1

plus

Azithromycin 1 g PO once

May substitute azithromycin with doxycycline 100 mg PO daily for 7 days

Gonorrhea,* adult conjunctivitis

Ceftriaxone 1 g IM × 1

Normal saline irrigation

Consider hospitalization

Gonorrhea,* disseminated infection

Ceftriaxone 1 g IM or IV every 24 hours

Strongly consider hospitalization

Cefotaxime 1 g IV q8h or

Ceftizoxime 1 g IV q8h

Syphilis; primary, secondary or early latent

Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM single dose

Syphilis, late latent

Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM in three doses, 1 week apart

Herpes simplex, first episode

Acyclovir 400 mg PO tid × 7-10 days or

Acyclovir 200 mg PO 5×/day × 7-10 days or

Famciclovir 250 mg PO tid × 7-10 days or

Valacyclovir 1 g PO bid × 7-10 days

Herpes simplex, recurrent

Acyclovir 400 mg PO tid × 5 days or

Acyclovir 800 mg PO bid × 5 days or

Acyclovir 800 mg PO tid × 2 days or

Famciclovir 125 mg PO bid × 5 days or

Famciclovir 1000 mg PO bid × 1 day or

Famciclovir 500 mg PO once, then 250 mg PO bid for 2 days or

Valacyclovir 500 mg PO bid for 3 days or

Valacyclovir 1 g PO qd × 5 days or

Valacyclovir 500 mg PO bid × 3 days

Herpes simplex, suppressive

Acyclovir 400 mg PO bid or

Famciclovir 250 mg PO bid or

Valacyclovir 500 mg PO qd or

Valacyclovir 1 g PO qd

Chancroid

Azithromycin 1 g PO once or

Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM once or

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO bid × 3 days or

Erythromycin base 500 mg PO tid × 7 days

Lymphogranuloma venereum

Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid × 21 days

Erythromycin base 500 mg PO qid × 21 days

Syphilis

Diagnosis

Treatment

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Anesthesia Key

Fastest Anesthesia & Intensive Care & Emergency Medicine Insight Engine