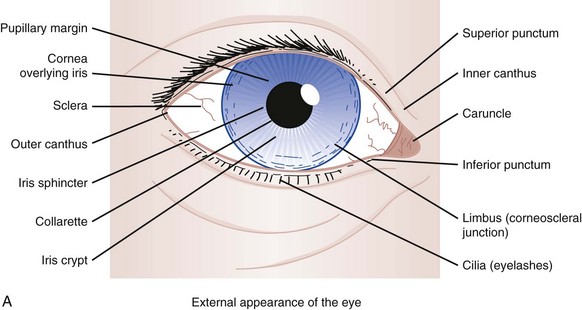

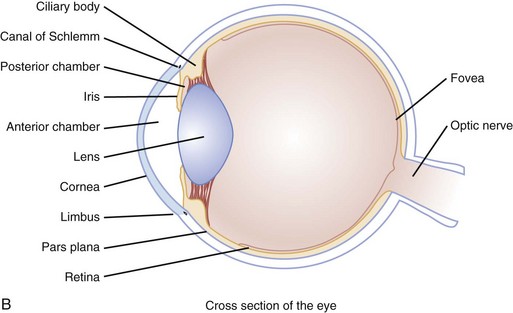

Chapter 22 Epidemiology and Pathophysiology Most eye complaints are not immediately sight-threatening and can be managed by an emergency physician. Nontraumatic diseases, such as glaucoma and peripheral vascular disease leading to retinal ischemia, are more common with advancing age. Ocular injuries are the leading cause of visual impairment and blindness in the United States.1 More patients with postoperative complications can be expected to visit the emergency department (ED) as more vision correction surgeries are performed. The external and internal anatomy of the eye is depicted in Figure 22-1A and B. The globe has a complex layer of blood vessels in the conjunctiva, sclera, and retina. Redness reflects vascular dilation and may occur with processes that produce inflammation of the eye or surrounding tissues. Eye pain may originate from the cornea, conjunctiva, iris, or vasculature. Each is sensitive to processes causing irritation or inflammation. Measurement of the patient’s best corrected visual acuity (i.e., with glasses on, if available) with each eye individually and with both eyes together provides vital information in evaluation of eye complaints. Only a few situations preclude early and accurate visual acuity testing. Eyes exposed to caustic materials should be irrigated as soon as possible. Patients with sudden and complete visual loss in one eye require prompt funduscopic examination to determine the possibility of acute central retinal artery occlusion. This condition is readily apparent as a diffusely pale retina with indistinct or unseen retinal arteries (Fig. 22-2). Other pivotal findings, which are more likely to be associated with a serious diagnosis, in patients with a red or painful eye are listed in Box 22-1. Other eye status review questions include the following: • Are contact lenses used? If so, what type, how are they cleaned, and how old are the lenses? Has there been a change in the pattern of use (especially increased use)? Were the lenses worn for a particularly long period recently? Are there problems with the lenses drying out? Does insertion of the lenses worsen or relieve the symptoms? Contact lenses alter the physiology of the cornea, making it relatively hypoxic, drier, and more susceptible to bacterial infection with subsequent ulceration. • Are glasses worn? If so, when was the last assessment for adequate refraction? When the patient is examined for objective abnormalities in visual acuity, the patient’s subjective interpretation of changes from his or her baseline may be all that is available when corrective lenses are not available or their prescription is out of date. • Has previous injury or eye surgery occurred? Abnormal examination findings, such as an eccentric or irregularly shaped pupil, may be the patient’s baseline. Pain and redness are expected shortly after eye surgery, but many surgical complications also manifest with a red and painful eye. • What is the patient’s usual state of health? Several systemic diseases may cause symptoms and signs in and around the eye. Giant-cell arteritis is a vasculitis with subacute systemic manifestations but often acute eye complaints. • What medications are being taken? Medications that affect the sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous systems may affect ocular physiology, such as aqueous production, or pupil size and reactivity. Bleeding may be potentiated by anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications. • Are there any known or suspected allergies? Environmental allergens are a common cause of conjunctivitis. Other superficial manifestations can be from chemicals (e.g., contact lens-cleaning solution) or other materials (e.g., makeup). A complete eye examination usually includes eight components, although many patients require only a limited or directed eye examination, depending on the presentation. The mnemonic VVEEPP (pronounced “veep”) plus slit-lamp and funduscopic examinations represent these components (Box 22-2). Slit-lamp examination is recommended for any complaint involving trauma and for any medical presentation involving foreign body sensation or alteration of vision. Funduscopic examination is usually pursued if there is visual loss, visual alteration, or suggestion of serious pathology in the history and initial physical examination. A thorough physical examination can be conducted in the following order. Gross abnormalities are assessed by a visual inspection of both eyes simultaneously. Findings may be more apparent if compared with the opposite side. Fractures of facial bones are associated with ocular injuries, some of which require immediate intervention by an ophthalmologist.2 Conjunctivitis is a common diagnosis after evaluation of patients with red and painful eyes, but determination of cause is much more difficult on clinical grounds. Patients may be unaware of exposures that could cause a chemical conjunctivitis. Without a known history of environmental allergies or other symptoms and signs to suggest an allergic reaction, allergic conjunctivitis may be mistaken for an infection. However, these are usually managed with removal of any known offending agent and symptomatic relief only. On the other hand, acute infectious conjunctivitis can be bacterial or viral, and management should ideally be directed toward the specific microbiologic cause. The acute management of infectious conjunctivitis accounts for over one-half billion dollars in indirect lost productivity and direct costs of antibiotic prescriptions,3 when many patients do not need them.4 The presence of punctate “follicles” (i.e., hypertrophy of lymphoid tissue in Bruch’s glands) along the conjunctival surfaces of one or both lower lids has been touted to be relatively specific for a nonbacterial (i.e., viral or toxic) cause—though one notable exception is trachoma, a chronic keratoconjunctivitis caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. Indeed, the “typical” viral “pinkeye” has been called acute follicular conjunctivitis.5 Some authorities also believe that the mucoid discharge associated with viral conjunctivitis can be clinically differentiated from the purulent discharge associated with bacterial infection.6 However, most research studying the association of symptoms and signs with positive bacterial cultures have grouped “mucoid or purulent” discharges into one finding, not requiring primary care physician participants to discriminate between the two during data collection.7,8 Thus no experimental evidence supports or refutes these expert opinions.9 Eyelids sticking together, particularly in the morning, is commonly cited as clinical evidence of bacterial, as opposed to viral, conjunctivitis, but this is unreliable. One multicenter primary care study in the Netherlands used logistic regression analysis to conclude that its presence plus the absence of itch and a prior history of conjunctivitis was associated with bacterial conjunctivitis; however, the 95% confidence intervals for the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve ranged from 0.63 to 0.80, thus making it a poor to only fair clinical prediction rule.7 In a single U.S. pediatric ED spanning ages from 1 month to 18 years, a similar analysis found sticky eyelids and either mucoid or purulent discharge to have a positive likelihood ratio of 3.1, and a post-test probability of 96% for positive bacterial cultures in their population; however, this likelihood ratio also indicates only a poor-to-fair test.8 Viral cultures were not performed in either of these studies, so the possibilities of copathogens or bacterial culture of nonpathogenic flora was not assessed. Therefore no good evidence exists for differentiating bacterial from viral causes on clinical grounds.

Red and Painful Eye

Perspective

Diagnostic Approach

Pivotal Findings

History

Physical Examination

External Examination

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Red and Painful Eye

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue