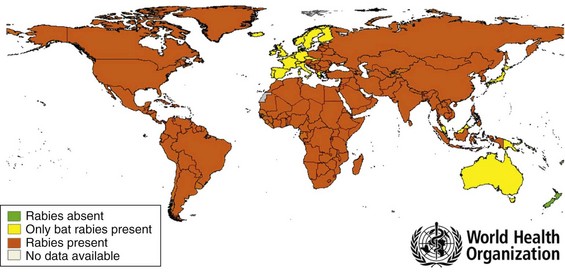

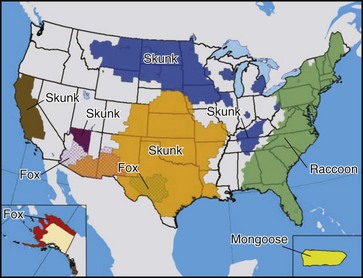

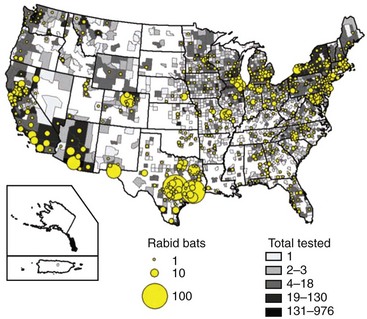

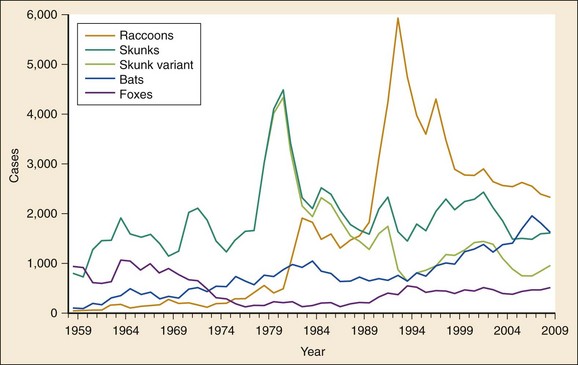

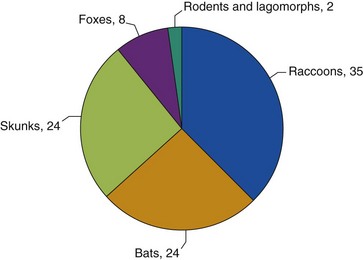

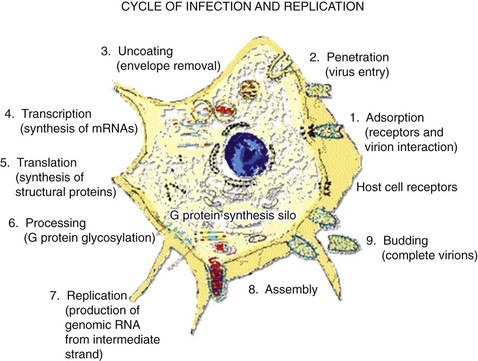

Chapter 131 Rabies is arguably the oldest infection known to humans. The term rabies comes from the Sanskrit rabhas, which means “to do violence.” The Eshmuna Code of Babylon, from the 23rd century BCE, contains one of the earliest regulations regarding rabies: a fine of 40 shekels was levied on the owner of a dog that killed another man through a rabid bite.1,2 Today, rabies is a huge public health problem in Third World countries; according to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 55,000 deaths from rabies occur annually worldwide, with 95% of those deaths occurring in Asia and Africa (Fig. 131-1).3 In the United States and Puerto Rico, however, human rabies is extremely rare as a result of a successful vaccination program for domestic animals that began in 1947. In the prevaccination era, approximately 40 human cases were reported each year. By contrast, in 2009 only four cases of human rabies, of which three were acquired in the United States, were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4–7 Although it is believed that any mammal can contract rabies, species within the orders Carnivora and Chiroptera (bats) are considered to be the most important reservoirs for maintenance and transmission of the disease.8–10 Worldwide, dogs are the most commonly infected animal and the most common source of rabies in humans. Dogs are the primary reservoir of rabies in Asia and in many developing countries of Africa. Although dogs were one of the principal reservoirs in South America, major reduction in human and dog rabies has been observed in the last 20 years since implementation of programs to eliminate rabies.11 In Europe, Canada, and the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions, the principal carrier is the fox; in Puerto Rico, it is the mongoose. Jackals are the main wildlife reservoir of rabies in Africa. Bats are an important source of human rabies in North and South America, western Europe, and Australia. Bats carrying rabies-related lyssaviruses also are found in Africa. In the United States, more than 90% of all cases of rabies occur in wild animals; the principal reservoirs are raccoons, bats, skunks, and foxes5 (Fig. 131-2). The only state that remains rabies free is Hawaii, where there are no rabid bats or rabid terrestrial animals.5 Rabies in terrestrial animals occurs in discrete geographic regions where the virus is transmitted primarily among members of a single species (Fig. 131-3). Each species and location is associated with a unique variant of the rabies virus. In the United States, for example, rabies is endemic in raccoons along the eastern seaboard. A different strain of virus is carried by skunks in the north central states; two additional distinctive strains carried by the skunks in the south central states and rabid skunks endemic to California have been associated with switching of reservoirs from bats to carnivores.5 Two gray fox reservoirs, each with a unique rabies virus variant, are found in Arizona and in Texas. Wherever rabies is endemic, other wild carnivores or domestic animals may become infected by contact with the endemic species and will carry the viral variant of the endemic species (“spillover”). The increase in skunk rabies in New England is largely attributable to the raccoon epizootic that has occurred there, although some of the skunk rabies has resulted from spillover from foxes. Although rabies has never been transmitted from a rodent or lagomorph (rabbit or hare) to humans, these animals do contract rabies, usually from the terrestrial reservoir in their region. Most rodent cases are found in larger rodents, such as groundhogs or beavers. In the United States, infected groundhogs generally are found in areas in which raccoon rabies is endemic.5 Rabid bats are ubiquitous throughout the United States and North America and account for 24% of all cases of rabies in U.S. animals, making them the second most common source of rabies in the United States after raccoons (Fig. 131-4); 6% of all bats submitted to state health departments tested positive for rabies in 2006. As with terrestrial reservoirs, bats carry viral variants unique to that species, but the geographic associations are less distinct, relating only to where a particular species of bats makes its home. Rabid bats are capable of infecting terrestrial animals as well as humans in any area of the mainland United States. However, spillover appears to be extremely rare.12 The association of a unique rabies virus variant with a particular species and locale makes it possible to determine the source of rabies in areas or species that previously were rabies free. In addition, antigenic typing permits identification of the source of human infections when the animal contact is unknown.13,14 Since the 1950s, rabies in U.S. domestic animals has significantly decreased, but the population of rabid wild animals has actually increased (Fig. 131-5). In 2009, rabies was reported in 6195 wild animals, compared with 7364 in 2000.5,15 In the 1960s and 1970s, a majority of cases of wildlife rabies were found in skunks in the United States. However, in the late 1970s, an epizootic among raccoons began in the mid-Atlantic states and spread north and south to cover the entire eastern seaboard; in 2009, more cases of wildlife rabies in the United States were attributable to raccoons than to any other wild animal (2327 or 34.8%). The likely source of this epizootic appears to be the inadvertent translocation of rabid raccoons from the southeastern states to the mid-Atlantic region by humans to stock the area for hunting, as evidenced by the fact that rabid raccoons, seen first in the mid-Atlantic states and now along the entire East Coast, carry the same viral variant as those in the southeastern states. The population has spread geographically north and westward. Raccoon rabies is now enzootic in all of the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and southeastern states.5,16,17 Of the rabid animal populations in the United States, bats now represent the second most populous (24.3%). A smaller epizootic of coyotes began in the early 1990s in southern Texas; three rabid coyotes were reported in 1990 and 71 in 1993, but the population has since returned to low levels. Eleven cases of coyote rabies were reported in 2009, and they were infected with skunk or gray fox virus variants.5,18,19 The number of rabid domestic animals has remained relatively constant for the last decade and accounted for approximately 8% (547 cases) of all rabies in the United States.5 Cats are the domestic animal most frequently reported as rabid, followed by dogs. An overall slight increase in the number of rabid cattle since 2008 has also been noted. The median age of rabid cats and dogs is 1 year; most have not been vaccinated or have received only one vaccination.20 Dogs and cats generally are infected with a strain of rabies virus that is endemic in the terrestrial reservoir in their geographic area. Puerto Rico reported a total of four cases of cat rabies in 2009, which is a presumed spillover from mongoose variant.5,21 Most owners are unaware of their pets’ exposure to wild animals that may carry rabies. Human cases of rabies in the United States remain low owing to effective animal vaccination programs and availability of human vaccines and immune globulins.5 Between 2000 and 2010, 31 cases of human rabies were reported to the CDC, 25 of which were acquired from animal sources in the United States. The first ever case of abortive human rabies was reported in 2009 from Texas after exposure to bats.22 Among the other reported human cases, one case was associated with the raccoon variant from the eastern United States, one case was due to a dog-mongoose variant in Puerto Rico, and the rest were associated with bats.5,23–34 Four cases were in transplant recipients, from a donor who died of an unknown encephalopathy, only later identified as rabies.32 For most bat-associated cases, a history of bat contact was discovered only during hospitalization or determined after the patient’s death, when antigenic analysis of the rabies virus infecting the victim revealed a bat variant. In more than half of the cases, the victim was known to have had contact with a bat, although no rabies prophylaxis was sought.* In most other cases, a history of bat exposure was lacking (so-called cryptogenic bat rabies).24,25,28,31 Although rabies has been found in most of the bat species in the United States, the species most frequently identified with cryptogenic bat rabies in humans is the silver-haired, eastern pipistrelle bat, a solitary, reclusive, tree-dwelling species that is seldom found in buildings and is thought to be rarely encountered by humans. The viral strain associated with this species appears to replicate better and at lower temperatures than a canine rabies variant, suggesting that even a small, superficially administered quantity of virus is sufficient to transmit infection.9,13 In 2008 the first case of imported human rabies not associated with canine rabies virus variant was reported from Santa Barbara County, California, in an undocumented immigrant from Mexico. Although the investigations were limited by the subject’s linguistic barrier and undocumented status in the United States, laboratory investigations revealed a rabies virus variant most closely related to viruses found in Mexican free-tailed bats.37 Another case of human rabies was reported in a subject from Virginia who described an encounter with a dog during his visit to India. Postmortem investigations confirmed the presence of an Indian canine rabies variant.38 Most recently, an 8-year-old girl from rural Humboldt County, California, was reported to have survived a rabies infection. Because the date of exposure was not known, she did not received routine postexposure prophylaxis. Furthermore, although the source animal was thought to be a feral cat, this could not be confirmed as the animal was not available for testing.39 Rabies is caused by a neurotropic rhabdovirus of the genus Lyssavirus (from the Greek word lyssa, which means “frenzy”). Animals are the natural reservoir for the virus; animals that are infected with the virus become sick and die, usually within 3 to 9 days of the time they first begin secreting virus in the saliva.40 Insectivorous bats may live 10 days; vampire bats, possibly longer.41,42 Some evidence suggests that dogs can become asymptomatic carriers, but transmission of disease from such an animal to humans has never been documented.43 A survey of rabid dogs in the United States in 1988 found that all died within 8 days of becoming ill; the median time until death was 3 days.20 Animals are capable of transmitting rabies once they start secreting virus in saliva. Most animals with rabies will appear ill before excretion of virus, but some may not become sick for several days after virus can be found in their saliva.42 The classic picture of a mangy dog foaming at the mouth and wildly running through town is not often seen; clinical signs are invariably present but frequently are more subtle. Indeed, less than half of cases of rabies in domestic animals are initially recognized by veterinarians.20 The animal may display aggressive behavior, ataxia, irritability, anorexia, lethargy, or excessive salivation; cats are more likely than dogs to demonstrate aggressive or irritable behavior. In a wild animal, however, what may be most apparent is a change in instinctive behavior, for instance, a nocturnal animal may be observed boldly walking through downtown in broad daylight.44 An unprovoked bite from a domestic animal may be a sign of rabies; however, humans, especially children, often inadvertently provoke a pet by cornering it or competing with it for its natural prey. Rabies is transmitted when the virus is introduced into bite wounds or open cuts in skin or onto mucous membranes.45 Almost all documented cases of human rabies have been transmitted by a bite. The risk of transmission by a bite is approximately 50 times that with a scratch46; rabies also has been contracted by recipients of corneal and organ transplants from infected donors.32,45 In animals, rabies is known to be transmitted transplacentally and has been shown to be transmissible experimentally by aerosol under artificial and extreme conditions and by ingestion.8,47 Other than through transplants, human-to-human transmission has never been confirmed, although two possible cases in family members of rabies victims in Ethiopia that were not laboratory confirmed have been described.48 Rabies virus has never been isolated from blood. The virus replicates in muscle cells near the site of the bite, remaining at the site of inoculation for most of the incubation period before entering the peripheral nerve by way of the neuromuscular junction and then rapidly ascending by retrograde conduction along peripheral nerves to the central nervous system. It is estimated that the virus travels along motor and sensory axons at a rate of approximately 8 to 20 mm/day and has a predilection for the thalamus, basal ganglia, and brainstem.49 Once it is in the central nervous system, the virus creates Negri bodies in the nuclei of neurons, where it manufactures copies of itself that then bud out to infect other neurons (Fig. 131- 6). Virus then is transported through the peripheral nerves by antegrade conduction to the salivary glands, where it can be excreted and transmit the disease to a new victim through a bite.50 Figure 131-6 Life cycle of the rabies virus within the host cell. (Modified from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: The rabies virus. Available at www.cdc.gov/rabies/transmission/virus.html. Accessed April 17, 2011.) Of interest, the virus does not destroy the neurons; in fact, it prevents cell apoptosis. How rabies actually kills humans has therefore been something of a mystery. Recent theories suggest that in the presence of the rabies virus, there is an outpouring of cytokines and proinflammatory molecules that modify electrical activity in the brain and affect the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and serotonin metabolism, causing the clinical symptoms. The immune reaction recruits T and B cells and results in more cytokine and nitric oxide production. Eventually, cells are depleted of all metabolic pools, and cell death then occurs. Thus the body’s own immune reaction may be the actual cause of death. This theory is supported by the fact that persons who have intact T-cell immunity are more likely to have encephalitic rabies and to die quickly, whereas those with impaired immunity are more likely to have paralytic rabies and to live longer.51 The risk for development of rabies and succumbing after a bite ranges from 5 to 80% and depends on the type of biting animal, the severity of the exposure, and the location of the bite.46,52 Clinical rabies progresses through five stages: incubation, prodrome, acute neurologic illness, coma, and death. The incubation period (bite to first symptom) typically is 20 to 90 days but has been documented to be as short as 10 days and as long as 7 years.46,52 The duration of the incubation period depends on the amount of viral inoculum, the richness of the peripheral nerve supply, the severity of the bite, the age and immune status of the host, and the proximity of the bite to the central nervous system.53 Bites on the head and neck result in disease with a shorter incubation period (as short as 15 days) than that for bites on the trunk or lower extremity, most likely because of the rich peripheral nerve supply in the head and neck area.54 The mortality rate is lower among victims with lower extremity bites.53 The acute neurologic syndrome that follows the prodromal phase will vary according to the type of rabies that is being manifested. Full-blown rabies has two classic forms: the “furious” or encephalitic form and the paralytic or “dumb” form; another, more recently identified form, “nonclassic,” also has been described.51 Encephalitic rabies is the far more common of the classic forms and is manifested by agitation, hydrophobia, fluctuating consciousness, and extreme irritability; periods of hyperexcitability fluctuate with lucidity or lethargy. Vital signs often are abnormal, with tachycardia, tachypnea, and fever. Hyperactivity is aggravated by light, noise, thirst, and fear. Hydrophobia, so named because of patients’ inability to swallow, appears to result from an exaggerated respiratory tract protective reflex that causes a violent, jerky contraction of the diaphragm and accessory muscles of inspiration when the patient attempts to swallow liquids.49 Overwhelming terror accompanies the phenomenon and may generalize to the sight of water or having water touch the face.55 Aerophobia, an extreme fear of air in motion, can be elicited in some patients by blowing air across the face. This results in muscle spasms in the neck and pharyngeal regions.56,57 Signs of autonomic dysfunction, such as excessive salivation and priapism, may be seen. Hyperactive deep tendon reflexes with Babinski’s signs and nuchal rigidity often are present. Seizures and focal weakness are rare. Approximately 20% of cases are manifested as paralytic or dumb rabies, with limb weakness and fever; consciousness initially is spared. Commonly, paralytic rabies has a longer duration of illness; the mean duration of illness before death is 13.4 days versus 7 days in the encephalitic form. Paralytic rabies may be difficult to diagnose because of the lack of the typical irritability and hydrophobia and may be confused with Guillain-Barré syndrome. It also may be difficult to make a distinction between the paralytic form of rabies and Guillain-Barré syndrome on the basis of clinical, pathologic, or electrophysiologic criteria. Features that may suggest paralytic rabies instead of Guillain-Barré syndrome include rapid progression of symptoms involving the central nervous system, asymmetry of limb involvement, persistent fever from the onset of limb weakness, intact sensory function except at the bite site, bladder dysfunction, and percussion myoedema (a mounding of the muscle at the percussion site that lasts a few seconds, most easily elicited on the chest, deltoid, and thigh).51,54 Neuropathologic findings of motor axon neuropathy in the absence of motor neuron degeneration and inflammation also may help with the recognition of paralytic rabies, although these findings are not unique to rabies.58 The two forms of classic rabies can overlap or progress from one to the other. Coma eventually occurs in all forms of rabies, generally 7 to 10 days after the onset of the acute neurologic phase. Hydrophobia persists, accompanied by prolonged apnea and generalized flaccid paralysis. Seizures may ensue, and ultimately the disease culminates in respiratory and vascular collapse. Unless the patient is supported by intensive care, death ensues in 2 to 3 days.59

Rabies

Perspective

Epidemiology

Wild and Domestic Animal Rabies

Rabies in Humans

Principles of Disease

Clinical Features

Rabies

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree