Preoperative Patient Assessment and Management

Tara M. Hata

J. Steven Hata

Key Points

Related Matter

Airway Exam

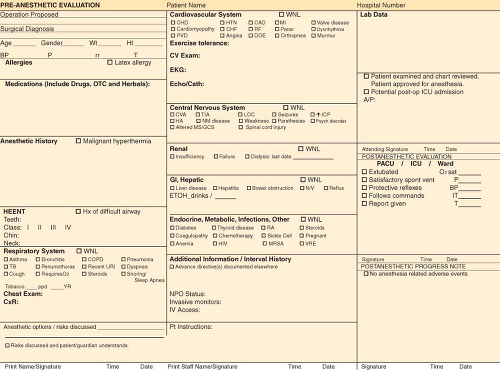

The preoperative evaluation has several components and goals. One should review the available medical record, obtain a history, and perform a physical examination pertinent to the patient and contemplated surgery. On the basis of the history and physical examination, the appropriate laboratory tests and preoperative consultations should be obtained. Through these, one needs to determine whether the patient’s preoperative condition may be improved prior to surgery. Guided by these factors, the anesthesiologist should choose the appropriate anesthetic and care plan. Finally, the process should be used to educate the patient about anesthesia and the perioperative period, answer all questions, and obtain informed consent.

The first part of this chapter outlines clinical risk factors pertinent to patients scheduled for anesthesia and surgery and the use of tests to confirm diagnoses. The second part discusses preoperative medication. The chapter provides only an overview of the preoperative management process; for more details, the reader is referred to chapters focusing on specific organ systems.

Changing Concepts in Preoperative Evaluation

In the past, patients were admitted to the hospital at least a day prior to surgery. Currently, more and more patients are admitted to the hospital from the postanesthesia care unit. Older patients are scheduled for more complex procedures, and there is more pressure on the anesthesiologist to reduce the time between cases. The first time that the anesthesiologist performing the anesthetic sees the patient may be just prior to anesthesia and surgery. Others may have seen the patient previously in a preoperative evaluation clinic. Only a short time exists to engender trust and answer last-minute questions. It is often impossible to alter medical therapy immediately preoperatively. However, preoperative screening clinics are becoming more effective and clinical practice guidelines are becoming more prevalent. Information technology has helped the anesthesiologist in previewing the upcoming patients who will be anesthetized. Preoperative questionnaires and computer-driven programs have become alternatives to traditional information gathering. Finally, when anesthesiologists are responsible for ordering preoperative laboratory tests, cost saving occurs and cancellations of planned surgical procedures become less likely. In this setting it is important that there is communication between the preoperative evaluation clinic and the anesthesiologist performing the anesthetic.

Approach to the Healthy Patient

The approach to the patient should always begin with a thorough history and physical examination. These two evaluations alone may be sufficient (without additional routine laboratory tests).

Indication for the Surgical Procedure. This is part of the preoperative history because it will help determine the urgency of the surgery. True emergency procedures, which are associated with a recognized higher anesthetic morbidity and mortality, require a more abbreviated evaluation. A less defined area is the approach to urgent procedures. For example, ischemic limbs require surgery soon after presentation, but can usually be delayed for 24 hours for further evaluation. The indication for the surgical procedure may also have implications on other aspects of perioperative management. For example, the presence of a small bowel obstruction has implications regarding the risk of aspiration and the need for a rapid sequence induction. The extent of a lung resection will dictate the need for further pulmonary testing and perioperative monitoring. Patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy may require a more extensive neurologic examination, as well as testing to rule out coronary artery disease (CAD). The planned procedure also dictates patient positioning and often whether blood products

will be necessary. Frequently, further information will be required that necessitates contacting the surgeon. Perioperative care of the patient, as well as efficiency in the OR, is always enhanced by close communication with the surgeons.

will be necessary. Frequently, further information will be required that necessitates contacting the surgeon. Perioperative care of the patient, as well as efficiency in the OR, is always enhanced by close communication with the surgeons.

Perhaps not life threatening, but persistent nausea and vomiting after a previous surgery may be the patient’s most negative and lasting memory. There are multiple predictors for postoperative nausea and vomiting, including the type of surgical procedure, the anesthetic agents, as well as patient factors. A risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting after inhalation anesthesia identified four risk factors: female gender, prior history of motion sickness or postoperative nausea, nonsmoking, and the use of postoperative opioids. The investigators suggested prophylactic antiemetic therapy when two or more of the risk factors were present when using volatile anesthetics.2,3 However, armed with this knowledge preoperatively, the anesthesiologist is able to tailor the anesthetic or possibly avoid general anesthesia and opioids altogether.

If the patient presents on the day of surgery, the anesthesiologist should determine when the patient last ate, as well as note the sites of preexisting intravenous cannulae and invasive monitors. Once the general issues are completed, the preoperative history and physical examination can focus on specific systems.

Screening Patients Using a Systems Approach

Airway

At the forefront of every anesthesiologist’s mind is the concern about the patient’s airway. Questions to address include

whether there is potential for difficulty in maintaining a patent airway with a mask and a laryngeal mask airway or in the ability to place an endotracheal tube when the patient is under general anesthesia. The ability to review previous anesthetic records is especially useful in uncovering an unsuspected “difficult airway” or to confirm previous uneventful intubations, noting whether the patient’s body habitus has changed in the interim. Patients should be questioned about their ability to breathe through their nose, whether there is suspected or diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and whether they have orthopnea. Evaluation of the airway involves examination of the oral cavity including dentition, determination of the thyromental distance, assessment of the size of the patient’s neck and scanning for tracheal deviation or masses, as well as evaluation of their ability to flex the base of the neck and extend the head. For trauma patients or patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis or Down syndrome, assessment of the cervical spine is critical. The presence of symptoms or signs of cervical cord compression should be assessed. In some instances, radiographic examination may also be required.

whether there is potential for difficulty in maintaining a patent airway with a mask and a laryngeal mask airway or in the ability to place an endotracheal tube when the patient is under general anesthesia. The ability to review previous anesthetic records is especially useful in uncovering an unsuspected “difficult airway” or to confirm previous uneventful intubations, noting whether the patient’s body habitus has changed in the interim. Patients should be questioned about their ability to breathe through their nose, whether there is suspected or diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and whether they have orthopnea. Evaluation of the airway involves examination of the oral cavity including dentition, determination of the thyromental distance, assessment of the size of the patient’s neck and scanning for tracheal deviation or masses, as well as evaluation of their ability to flex the base of the neck and extend the head. For trauma patients or patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis or Down syndrome, assessment of the cervical spine is critical. The presence of symptoms or signs of cervical cord compression should be assessed. In some instances, radiographic examination may also be required.

Table 22-1. Herbal/Dietary Supplements and Drug Interactions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Mallampati classification has become the standard for assessing the relationship of the tongue size relative to the oral cavity (Table 22-2),4 although by itself the Mallampati classification has a low positive predictive value in identifying patients who are difficult to intubate.5,6 Intubation involves multiple steps: Flexion of the neck, extension of the head, opening the mouth to insert the laryngoscope, and displacing the tongue forward and down into the submandibular space to expose the glottis. Therefore, a multifactorial approach to predict intubation difficulty as shown in Table 22-3 has proven more helpful. One must keep in

mind that factors that predict a difficult intubation are not necessarily the same factors that predict a difficult mask airway. For example, the absence of teeth clearly makes laryngoscopy less difficult, but at the same time can make maintaining a mask airway more challenging.

mind that factors that predict a difficult intubation are not necessarily the same factors that predict a difficult mask airway. For example, the absence of teeth clearly makes laryngoscopy less difficult, but at the same time can make maintaining a mask airway more challenging.

Table 22-2. Modified Mallampati Airway Classification System | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

Pulmonary System

A screening evaluation should include questions regarding the history of tobacco use, dyspnea, exercise tolerance, cough, wheezing, inhaler use, recent upper respiratory tract infection, stridor, and snoring or sleep apnea. Physical examination should assess the respiratory rate as well as the chest excursion, use of accessory muscles, nail color, and the patient’s ability to carry on a conversation or to walk without dyspnea. Auscultation should be used to detect decreased breath sounds, wheezing, stridor, or rales. For the patient with positive findings, see the section on the preoperative evaluation of the patient with pulmonary disease.

Table 22-3. Components of the Airway Examination Which Suggest Difficulty with Intubation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Cardiovascular System

The anesthesiologist should also be familiar with the American Heart Association (AHA) web site (http://www.heart.org/), which has links to the latest AHA statements and guidelines for health professionals. Here, one can find the most recent recommendations regarding which patients and procedures require subacute bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis.8

The examination of the cardiovascular system should include blood pressure evaluation, measuring both arms when appropriate. The anesthesiologist should take into account the effects of preoperative anxiety and may want a record of resting blood pressure measurements. However, Bedford and Feinstein9 reported that the admission blood pressure was the best predictor of HR and BP response to laryngoscopy. Auscultation of the heart is performed, specifically listening for a murmur radiating to the carotids suggestive of aortic stenosis, abnormal rhythms, or a gallop suggestive of heart failure. The presence of bruits over the carotid arteries would warrant further workup to determine the risk of stroke. The extremities should be examined for the presence of peripheral pulses to exclude peripheral vascular disease or congenital cardiovascular disease.

Neurologic System

A screening of the neurologic system in the apparently healthy patient can be accomplished through simple observation. The patient’s ability to answer health history questions practically ensures a normal mental status. Questions can be directed regarding a history of stroke and to exclude the presence of cerebrovascular disease, seizure history, preexisting neuromuscular disease, or nerve injuries. The neurologic examination may be cursory in healthy patients or extensive in patients with coexisting disease. Testing of strength, reflexes, and sensation may be important in

patients if the anesthetic plan or surgical procedure may result in a change in the condition.

patients if the anesthetic plan or surgical procedure may result in a change in the condition.

Table 22-4. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status (PS) Classification | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Endocrine System

Each patient should be questioned for symptoms that suggest endocrine diseases that may affect the perioperative course: diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, parathyroid disease, endocrine-secreting tumors, and adrenal cortical suppression.

Evaluation of the Patient with Known Systemic Disease

Cardiovascular Disease

The preoperative evaluation of the patient with suspected cardiovascular disease has been approached in two ways: Clinical risk indices and preoperative cardiac testing. The goals are to define risk, determine which patients will benefit from further testing, form an appropriate anesthetic plan, and identify patients who will benefit from perioperative beta-blockade, interventional therapy, or even surgery. Clinical risk indices range from the physical status index of the ASA (Table 22-4) to the Goldman Cardiac Risk Index, which has recently been updated.

In an update of the Goldman Cardiac Risk Index, the investigators studied 4,315 patients aged 50 years and older who were undergoing elective, major noncardiac procedures.10 Six independent predictors of complications were identified and included in a revised risk index: high-risk type of surgery, history of ischemic heart disease, history of congestive heart failure, history of cerebrovascular disease, preoperative treatment with insulin, and preoperative serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL. Cardiac complications rose with an increase in the number of risk factors present. Rates of major cardiac complications with 0, 1, 2, or 3 of these factors were 0.5%, 1.3%, 4%, and 9%, respectively, in the derivation cohort and 0.4%, 0.9%, 7%, and 11%, respectively, among 1,422 patients in the validation cohort (Fig. 22-2).

While all of these indices provide information to assess the probability of complications and provide an estimate of risk, they do not prescribe perioperative management. In contrast, the anesthesiologist is most concerned with forming an anesthetic plan after defining the cardiovascular risk factors.

In patients with symptomatic coronary disease, the preoperative evaluation may reveal a change in the frequency or pattern of anginal symptoms. Certain populations of patients—for example, the elderly, women, or diabetics—may present with more atypical features. The presence of unstable angina has been associated with a high perioperative risk of MI.7

In virtually all studies, the presence of active congestive heart failure preoperatively has been associated with an increased incidence of perioperative cardiac morbidity.11,12 Stabilization of ventricular function and treatment for pulmonary edema are important prior to elective surgery. Because the type of perioperative monitoring and treatments would be different, clarifying the cause of heart failure is important. Congestive symptoms may be a result of nonischemic cardiomyopathy or cardiac valvular insufficiency and/or stenosis.

Adults with a prior MI almost always have CAD. Traditionally, risk assessment for noncardiac surgery was based on the time interval between the MI and surgery. Multiple older studies have demonstrated an increased incidence of reinfarction if the MI was within 6 months of surgery.13,14,15 With improvements in perioperative care, this difference has decreased. Therefore, the importance of the intervening time interval may no longer be valid in the current era of interventional therapy and risk stratification after an acute MI. Although many patients with an MI may continue to have myocardium at risk for subsequent ischemia and infarction, other patients may have their critical coronary stenoses either totally occluded or widely patent. For example, the use of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, thrombolysis, and early coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has changed the natural history of the disease.16,17 Therefore, patients should be evaluated from the perspective of their risk for ongoing ischemia. The American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) Task Force on Perioperative Evaluation of the Cardiac Patient Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery has defined patient risk groups—based on clinical predictors (Table 22-5).18

Table 22-5. Clinical Predictors of Increased Perioperative Cardiovascular Risk (Myocardial Infarction, Congestive Heart Failure, Death) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Identifying Patients at Risk for Cardiac Disease

For those patients without overt symptoms or history, the probability of CAD varies with the type and number of atherosclerotic risk factors present. Peripheral arterial disease has been shown to be associated with CAD in multiple studies.19

Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is a common disease with a pathophysiology that affects multiple organ systems. Complications of diabetes

mellitus are frequently the cause of urgent or emergent surgery, especially in the elderly. Diabetes accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis, so it is not surprising that diabetics have a higher incidence of CAD than nondiabetics. There is a high incidence of both silent MI and myocardial ischemia.20 Eagle et al.21 demonstrated that diabetes is an independent risk factor for perioperative cardiac morbidity. The duration of the disease and other associated end-organ dysfunction may alter the overall cardiac risk. Autonomic neuropathy has been reported as the best predictor of silent CAD.22 Because these patients are at very high risk for a silent MI, an electrocardiogram (ECG) should be obtained to examine for the presence of Q waves.

mellitus are frequently the cause of urgent or emergent surgery, especially in the elderly. Diabetes accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis, so it is not surprising that diabetics have a higher incidence of CAD than nondiabetics. There is a high incidence of both silent MI and myocardial ischemia.20 Eagle et al.21 demonstrated that diabetes is an independent risk factor for perioperative cardiac morbidity. The duration of the disease and other associated end-organ dysfunction may alter the overall cardiac risk. Autonomic neuropathy has been reported as the best predictor of silent CAD.22 Because these patients are at very high risk for a silent MI, an electrocardiogram (ECG) should be obtained to examine for the presence of Q waves.

Hypertension

Hypertension has also been associated with an increased incidence of silent myocardial ischemia and infarction.20 Hypertensive patients who have left ventricular hypertrophy and are undergoing noncardiac surgery are at a higher perioperative risk than nonhypertensive patients.23

Investigators have suggested that the presence of a strain pattern on ECG suggests a chronic ischemic state.24 Therefore, these patients should also be considered to have an increased probability of CAD and for perioperative morbidity.

There is controversy regarding a trigger to delay or cancel a surgical procedure in a patient with untreated or inadequately treated hypertension. Hypertension has been divided into three stages, with stage 3 denoting that which might be used as a cutoff (Table 22-6).25 Aggressive treatment of blood pressure is associated with increased reduction in long-term risk, although the effect diminishes in all but diabetic patients as diastolic blood pressure is reduced below 90 mm Hg. Although there has been a suggestion in the literature that a case should be delayed if the diastolic pressure is >110 mm Hg, the study often quoted as the basis for this determination demonstrated no major morbidity in that small group of patients.26 Other authors state that there is little association between blood pressures of <180 mm Hg systolic or 110 mm Hg diastolic and postoperative outcomes. However, such patients are prone to perioperative myocardial ischemia, ventricular dysrhythmias, and lability in blood pressure. It is less clear in patients with blood pressures above 180/110 mm Hg, although no absolute evidence exists that postponing surgery will reduce risk.27,28 In the absence of end-organ changes, such as renal insufficiency or left ventricular hypertrophy with strain, the benefits of optimizing blood pressure must be weighed against the risks of delaying surgery.

Table 22-6. Blood Pressure | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other Risk Factors

Several other factors associated with atherosclerosis have been used to suggest an increased probability of CAD. These include tobacco use and hypercholesterolemia. Although these risk factors increase the probability of developing CAD, they have not been shown to increase perioperative cardiac risk. When attempting to determine the overall probability of disease, the number of risk factors and severity of each are important.

Importance of Surgical Procedure

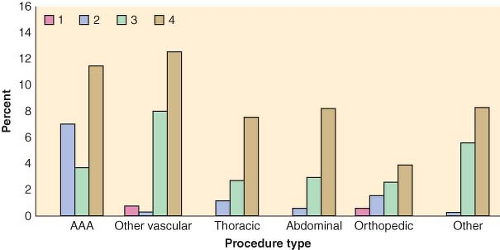

The surgical procedure influences the scope of preoperative evaluation required by determining the potential range of physiologic flux during the perioperative period. Few data exist defining the surgery-specific incidence of complications. Peripheral procedures, such as those included in a study of ambulatory surgery completed at the Mayo Clinic, are associated with an extremely low incidence of morbidity and mortality,29 while major vascular procedures are associated with the highest incidence of complications. The AHA/American College of Cardiology guidelines describe risk stratification for noncardiac surgery as shown in Table 22-7.18 Eagle et al.30 published data on the incidence of perioperative MI and mortality by procedure for patients enrolled in the Coronary Artery Surgery Study. They determined the overall

risk of perioperative morbidity in patients with known CAD treated either medically or with prior CABG. Their data differed slightly and found that high-risk procedures include major vascular, abdominal, thoracic, and orthopedic surgery.

risk of perioperative morbidity in patients with known CAD treated either medically or with prior CABG. Their data differed slightly and found that high-risk procedures include major vascular, abdominal, thoracic, and orthopedic surgery.

Table 22-7. Cardiac Riska Stratification Based on the Surgical Procedure in Patients with Known Coronary Artery Disease | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

Table 22-8. Estimated Energy Requirement for Various Activities | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

Importance of Exercise Tolerance

Reilly et al.31 have evaluated the predictive value of self-reported exercise tolerance for serious perioperative complications and demonstrated that a poor exercise tolerance (could not walk four blocks and climb two flights of stairs) independently predicted complications. The likelihood of a serious adverse event was inversely related to the number of blocks that could be walked. Therefore, there is good evidence to suggest that minimal additional testing is necessary if the patient is able to describe a good exercise tolerance.

Indications for Further Cardiac Testing

Multiple algorithms have been proposed to determine which patients require further testing. As described previously, the risk associated with the proposed surgical procedure influences the decision to perform further diagnostic testing and interventions. With the reduction in perioperative morbidity, it has been suggested that extensive cardiovascular testing is not necessary. However, until these findings can be confirmed, further testing may be warranted.

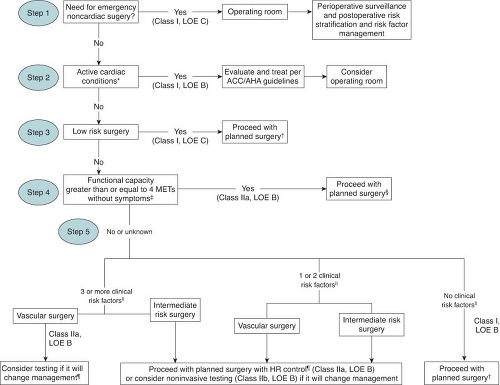

The algorithm to determine the need for testing proposed by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force updated in 2002 and again in 200732 is based on the available evidence and expert opinion that integrates clinical history, surgery-specific risk, and exercise tolerance. In the first step, the clinician evaluates the urgency of the surgery and the appropriateness of a formal preoperative assessment. Next, one should determine if the patient has undergone a recent revascularization procedure or coronary evaluation. Those patients with unstable coronary syndromes should be identified, and appropriate treatment instituted. Finally, the decision to undergo further testing depends on the interaction of the clinical risk factors, surgery-specific risk, and functional capacity. For patients at intermediate clinical risk, both exercise tolerance and the extent of the surgery are taken into account to determine the need for further testing. Importantly, no preoperative cardiovascular testing should be performed if the results will not change perioperative management.

Electrocardiogram

Preoperative 12-lead ECG can provide important information on the state of the patient’s myocardium and coronary circulation. Abnormal Q waves in high-risk patients are highly suggestive of a past MI. Confirmation of active ischemia usually requires changes in at least two leads. It has been estimated that approximately 30% of MIs occur without symptoms (“silent infarctions”) and can only be detected on routine ECGs, with the highest incidence occurring in patients with either diabetes or hypertension. The Framingham study showed that long-term prognosis is not improved by lack of symptoms.20 The absence of Q waves on the ECG does not exclude the occurrence of a Q-wave MI in the past. Between 5% and 27% of Q waves disappeared over the 10-year period following an infarction during the 1970s.33 Those patients in whom the ECG reverts to normal have improved survival compared with those with consistent abnormalities, with or without Q waves. The presence of Q waves on a preoperative ECG in a high-risk patient, regardless of symptoms, should alert the anesthesiologist to the increased perioperative risk and the possibility of active ischemia.

It has not been established that information obtained from the preoperative ECG affects clinical care. A review of clinical studies on the matter is inconclusive. In one retrospective review of adult patients undergoing ambulatory surgery, the preoperative ECG was not predictive of perioperative risk.34 Although controversy exists, there are current recommendations for the need for a preoperative ECG. A preoperative resting 12-lead ECG is recommended for patients with at least one clinical risk factor who are undergoing vascular surgical procedures and for patients with known CAD, peripheral arterial disease, or cerebrovascular

disease who are undergoing intermediate-risk surgical procedures. A perioperative ECG is reasonable in persons with no clinical risk factors who are about to undergo vascular surgical procedures and may be reasonable in patients with at least one clinical risk factor who are undergoing intermediate-risk operative procedures.32

disease who are undergoing intermediate-risk surgical procedures. A perioperative ECG is reasonable in persons with no clinical risk factors who are about to undergo vascular surgical procedures and may be reasonable in patients with at least one clinical risk factor who are undergoing intermediate-risk operative procedures.32

Noninvasive Cardiovascular Testing

The exercise ECG has been the traditional method in the past for evaluating patients with suspected CAD. It represents the most cost-effective and least invasive method for detecting ischemia, with a sensitivity of 70% to 80% and a specificity of 60% to 75% for identifying CAD. A positive exercise stress test alerts the anesthesiologist that the patient is at risk for ischemia associated with increased heart rate, with the greatest risk in those who develop ischemia only after mild exercise. However, as discussed previously, the ability to exercise suggests that no further testing is necessary, and therefore stress electrocardiography is infrequently indicated.

A number of high-risk patients are either unable to exercise or have contraindications to exercise, for example, those with claudication. Therefore, pharmacologic stress testing and ambulatory electrocardiography have come into vogue, particularly as preoperative cardiovascular tests in patients scheduled for vascular surgery. Pharmacologic stress thallium imaging is useful in those patients who are unable to exercise. Dipyridamole or adenosine is administered as a coronary vasodilator to assess flow heterogeneity. The presence of a redistribution defect is predictive of postoperative cardiac events, especially in patients undergoing peripheral vascular surgery. Similarly, dobutamine can be used to increase myocardial oxygen demand, by increasing heart rate and blood pressure, in those patients who cannot exercise.

The ambulatory ECG (e.g., Holter monitoring) provides a means of continuously monitoring the ECG for significant ST segment changes preoperatively. One study demonstrated that the presence of silent ischemia is a strong predictor of outcome, while its absence is associated with a favorable outcome in 99% of the patients studied.35 Other investigators have demonstrated the value of ambulatory ECG monitoring, although the negative predictive values have not been as high as reported by some.

Stress echocardiography is another preoperative test that may be of value in evaluating patients with suspected CAD. The appearance of either new or more severe regional wall motion abnormalities with exercise is considered a positive test. Either represents areas at risk for myocardial ischemia. The advantage of stress echocardiogram is that it is a dynamic assessment of ventricular function. Dobutamine echocardiography has also been studied and found to have among the best predictive values. It is generally accepted that the group at risk is composed of those who demonstrate regional wall motion abnormalities at low heart rates.

Several groups have published meta-analyses of preoperative diagnostic tests. One group of investigators demonstrated good predictive values using ambulatory ECG monitoring, radionuclide angiography, dipyridamole thallium imaging, or dobutamine stress echocardiography.36 Shaw et al.37 also demonstrated good predictive values of dipyridamole thallium imaging and dobutamine stress echocardiography. Both of these studies demonstrated the superior value of dobutamine stress echocardiography; however, there was significant overlap of the confidence intervals with other tests. The most important determinant with respect to the choice of preoperative testing is the expertise of the local institution.

Current recommendations are that patients with active cardiac conditions such as unstable angina, congestive heart failure, significant dysrhythmias, and severe valvular disease should undergo noninvasive stress testing before noncardiac surgery. Noninvasive stress testing for patients with multiple clinical risk factors and poor functional capacity (less than four metabolic equivalents) who require vascular surgery is reasonable if it will change management. Noninvasive testing in other patients about to go under intermediate-risk noncardiac surgery or vascular surgery is less clear.32

Assessment of Ventricular and Valvular Function

Both echocardiography and radionuclide angiography can assess cardiac ejection fraction at rest and under stress. Echocardiography is less invasive and able to assess regional wall motion abnormalities, wall thickness, valvular function, and valve area. Pulse-wave Doppler can be used to determine the velocity time integral. Ejection fraction can then be calculated by determining the cross-sectional area of the ventricle. Conflicting results exist with regard to the predictive value of ejection fraction using either echocardiographic or radionuclide measurements. It is reasonable for those with dyspnea of unknown origin and for those with current or prior heart failure with worsening dyspnea or other change in clinical status to have preoperative evaluations of left ventricular function. The benefits of reassessment of left ventricular function in clinically stable patients with previous cardiomyopathy are unknown.32 Echocardiography can provide important information regarding valvular function, which may have important implications for either cardiac or noncardiac surgery, and is discussed more fully later in this text. Aortic stenosis has been associated with a poor prognosis in noncardiac surgical patients, and knowledge of valvular lesions may modify perioperative hemodynamic therapy.11

Coronary Angiography

Coronary angiography is currently the best method for defining coronary anatomy. In addition, information regarding ventricular and valvular function can also be assessed. Hemodynamic indices can be determined such as ventricular pressures and pressure gradients across valves. This information is routinely available in patients scheduled for CABG. Narrowing of the left main coronary artery and certain other lesions may be associated with a greater perioperative risk. Diffuse atherosclerosis in small vessels, as seen in diabetics, may lead to incomplete revascularization and a risk of developing ischemia despite CABG. Coronary angiography is used by cardiologists to determine whether coronary vascularization is an option.

Unlike the exercise or pharmacologic stress tests discussed earlier, coronary angiography provides anatomic, not functional, information. Although a critical coronary stenosis delineates an area of risk for developing myocardial ischemia, the functional response of that ischemia cannot be assessed by angiography alone. A critical stenosis may or may not be the underlying cause for a perioperative MI that occurs. In the ambulatory population, many infarctions are the result of acute thrombosis of a noncritical stenosis. Therefore, the value of routine angiography prior to noncardiac surgery depends on the identification of lesions that will cause morbidity and mortality.

Patients with restricted physical activity in whom functional capacity is difficult to determine may benefit from sophisticated imaging techniques such as cardiac computed tomography.38

Perioperative Coronary Interventions

Guidelines to reduce the perioperative risk of noncardiac surgery have recently been reviewed. There are several large studies that suggest that in patients who survive CABG, the risk of subsequent noncardiac surgery is low.7,10 Although there is little data to support the notion of coronary revascularization solely for the purpose of improving perioperative outcome, it is true that for some patients scheduled for high-risk surgery, long-term survival may

be enhanced by revascularization. Two studies used the Coronary Artery Surgery Study database and found that CABG significantly improved survival in those patients with both peripheral vascular disease and triple-vessel coronary disease, especially the group with depressed ventricular function.39 After reviewing all available data, most clinicians believe the indication for CABG prior to noncardiac surgery remains the same as in other settings and is independent of the proposed noncardiac surgery.

be enhanced by revascularization. Two studies used the Coronary Artery Surgery Study database and found that CABG significantly improved survival in those patients with both peripheral vascular disease and triple-vessel coronary disease, especially the group with depressed ventricular function.39 After reviewing all available data, most clinicians believe the indication for CABG prior to noncardiac surgery remains the same as in other settings and is independent of the proposed noncardiac surgery.

The value of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty is less well established. The current evidence does not support the use of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty beyond established indications for nonoperative patients.

Patients with Coronary Artery Stents

Early surgery after coronary stent placement has been associated with adverse cardiac events. A significant incidence of perioperative death and of hemorrhage in patients after stent placement has been reported. The waiting period for surgery after bare metal stent placement is generally recognized as 1 month as a minimum, while the waiting period for drug-eluting stents is 12 months. This difference is because the incidence of stent thrombosis for the drug-eluting stents has been found to be similar to the bare metal stents in the early phase after placement, but less well defined over a longer period of time. Currently, patients are invariably taking aspirin and clopidogrel as antiplatelet therapy after stent placement. A thienopyridine (ticlopidine or clopidogrel) is generally continued with aspirin for 1 month after bare metal stenting and for 12 months after drug-eluting stent placement (Fig. 22-3). Perioperative management weighs the risk of bleeding versus a stent thrombosis. The decision must involve anesthesiologist, surgeons, cardiologists, and intensivists. For those patients who have a high risk for stent thrombosis, many advocate that at least aspirin be continued in the perioperative period. Also, the anesthesiologist must weigh the risk of regional versus general anesthesia when these patients are taking antiplatelet therapy. Surgery in patients with recent stent placement should probably only be considered in centers where 24-hour interventional cardiologists are available.40,41,42

Figure 22.3. Cardiac evaluation algorithm for patients at least 50 years with cardiac risk factors undergoing non-cardiac surgery. || Clinical risk factors include ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, renal insufficiency, compensated or history of congestive heart failure. AHA: American Heart Association; ACC: American College of Cardiology; HR; heart rate; LOE, level of evidence; MET: metabolic equivalent. (Used with permission from ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery. Circulation 2007;116:e418–e500.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|