Chapter 14 Preoperative assessment and day case surgery

Ian Smith Clare Hammond

SUMMARY

This chapter will describe:

• the current trends in day case surgery

• patient selection and clinical approaches to care

• future developments in day case practice.

INTRODUCTION

Preassessment before day surgery should aim to identify all those patients for whom, because of medical conditions or social circumstances, successful discharge on the day of operation would be unlikely or unsafe, or where complications thereafter would be highly probable. As with other forms of preassessment, every attempt should be made to ensure that the patient is optimally treated before elective surgery. Patients who, once optimally treated, are still likely to experience complications or will be difficult to manage during the operative period or in the early stages of recovery may still be suitable candidates for day surgery, provided these problems will have resolved by the time of intended discharge.

Day surgery can trace its origins back to the early 1900s,1 but it did not become particularly common until the late 1980s and has recently undergone a further expansion. Day surgery was once seen as a highly selective and specialised form of care, which was unsafe and undesirable in all but the fittest patients. As the practice has expanded, especially in North America and northern Europe, increasing experience and evidence show that this is not the case. Day surgery offers patients numerous clinical benefits2 and should be seen as the treatment of choice3,4 or default option, for a wide range of surgical procedures.5

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to consider all of the surgical procedures suitable for day surgery (for a comprehensive selection, see the British Association of Day Surgery’s Directory of Procedures5), but the advent of minimally invasive surgery means that much is now possible. Surgical prejudices must be challenged, paying particular attention to the likely timing of postoperative complications. Complications which occur early, and which would be detected by careful postoperative observation and a thorough review prior to discharge, or else which only occur after several days, when even inpatients would be at home, should not prevent day surgery.

Mechanism of day surgery preassessment

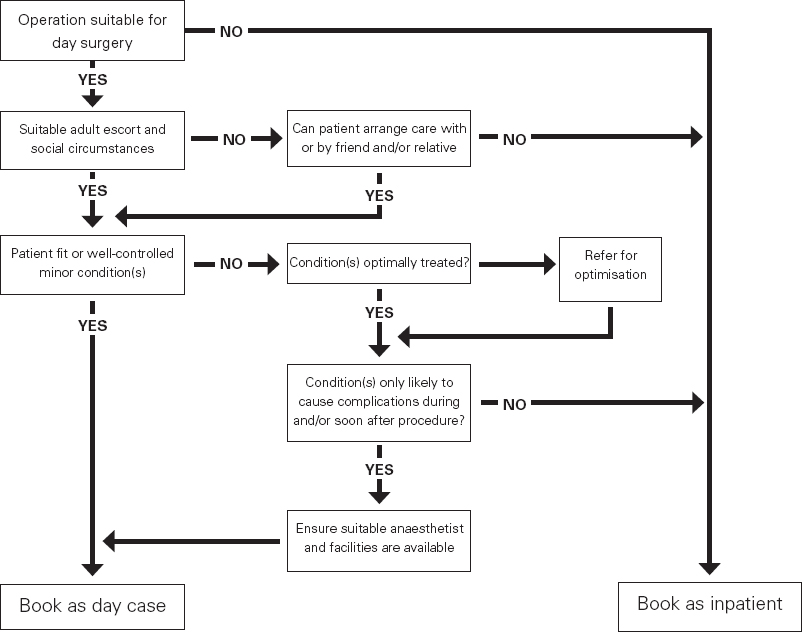

Once the decision to operate has been made, and if the intended surgical procedure is possible to perform as a day case, it should be the preassessment team who decide the individual patient’s final management.2,4,6,7 Day surgery should be considered as the default option,3,6 with inpatient care selected only if there are unsuitable social circumstances or legitimate medical concerns (see Figure 14.1). Current medical and social criteria for day surgery7–9 will be discussed later in this chapter.

Figure 14.1

Basic principles for the preassessment and selection of day case patients

Day surgery preassessment may be broken down into three components. First, there is the information gathering and health assessment necessary to determine the patient’s level of fitness and whether or not they are optimally treated. This process is essentially similar to other forms of preassessment before elective surgery. The second component is the decision as to whether the optimised patient is a suitable candidate for day surgery, or if they would be better managed as an inpatient. This requires specialist knowledge of the postoperative course of numerous procedures, as well as some of the specialised anaesthetic techniques which can be used to good effect in certain higher risk patients. The third component is information giving, since much of the success of day surgery comes from developing a positive mental attitude and preparing the patient to be able to cope outside the hospital environment. Patients need to be given a realistic idea of how much postoperative pain they will have and how this will be managed, as well as what support they will require and when they can safely resume various activities.

There is currently a preference for centralising all preassessment services, as this concentrates the valuable resource of nurses trained in health assessment. Centralised preassessment is also consistent with the default to day surgery philosophy, with every patient at least being considered for this form of care. However, the other two components of day surgery preassessment, as outlined above, are highly specialised and there are considerable advantages if preassessment is performed within the facility where day surgery will take place.8 Here will be found many nurses with the necessary specialist skills and ready access to specialist anaesthetists (and surgeons) who can usually give an instant opinion on the more difficult cases. Suitable preoperative information will also be available and there is an opportunity for the patient (and perhaps their carer) to familiarise themselves with the surgical facility. Despite the logistical advantages of centralised preassessment, there are definite advantages to segregating preassessment for services where day care is unlikely, such as cardiac, colorectal and major orthopaedic surgery, from those where it is a probable form of care. Alternatively, day surgery preassessment may function well as a ‘team within a team’.

Assessing fitness for day surgery

The health assessment of adults (preassessment of children for day surgery follows essentially the same principles as for any paediatric preassessment and is not considered in this chapter) presenting for day surgery is a clinical process which relies most heavily on the patient history. Although much attention is focused on acquiring clinical skills, such as chest auscultation, in the authors’ opinion this is rarely helpful. For example, a previously unknown cardiac murmur is unlikely to represent significant cardiac risk (or indicate the need for endocarditis prophylaxis) in the absence of any symptoms or physical limitation. Similarly, screening investigations rarely detect pathology which will significantly alter the intended management or eventual outcome. For example, ECGs are rarely abnormal (to a degree to cause concern or alter management) in the absence of symptoms or other cardiovascular risk factors, even in the elderly.10 Even screening for sickle cells is probably unnecessary in adults; the disease (which may very well dictate modification in anaesthetic or surgical management) should be clinically evident by adult life, whereas the presence of the trait (which is clinically undetectable) requires no change in management.

Obtaining the patient history can be achieved in a variety of ways, but most conveniently involves some sort of questionnaire (for an example, see AAGBI (2005)8). These can be completed at a face-to-face interview, over the telephone or internet, or can be sent home with the patient and returned by post. The format usually involves basic screening questions, with supplementary questions asked, if appropriate. Computerised versions can exploit the concept of selective questioning to a far greater degree and can also calculate perioperative risk and advise on appropriate management automatically.

Preassessment should ideally allow enough time to investigate and optimise patients, but not be so far in advance as to permit the patient’s condition to deteriorate further.6 It is most convenient for the patient if preassessment, or at least an initial health screen, is performed at the time of the surgical outpatients clinic and, with the move towards the 18-week wait, such a ‘one-stop shop’ will have to become the norm. Not all patients will require a formal face-to-face consultation as part of their health assessment, however, and screening questionnaires are often used to identify these healthier patients. Nevertheless, most patients will still benefit from the type of information which can be provided by a preassessment service.

Social selection criteria

The residual effects of general anaesthesia or sedation, combined with the sedative effects of some analgesic medications and the discomfort and dysfunction produced by the surgical procedure, mean that the patient’s fine judgement may be impaired for some time after surgery and they can be at risk from everyday activities. Patients must therefore be discharged into the care of a responsible adult who can ensure they remain safe and also summon help in the unlikely event of a serious problem. A somewhat arbitrary period of 24 hours is commonly recommended,11 although considerably longer may be required after some operations or in more frail individuals. Conversely, an escort is usually unnecessary after operations conducted under local anaesthesia, unless the surgery itself is significantly disabling. Patients also need easy access to a telephone, to summon assistance, and should have reasonable access to emergency care.

With an ageing population and increasing break-up of the family unit, many more patients now live alone, making them potentially unsuitable for day surgery. However, in many cases, adequate preparation time can allow them to make suitable arrangements to be accompanied by, or to stay with, a friend or family member. Such arrangements mean that these patients are not denied the benefits of day surgery, not least being the significant reduction in postoperative confusion in the elderly compared with inpatient care.12

In the United Kingdom, most patients will live within a few miles of their nearest hospital. However, if they have to stay with a relative postoperatively or need access to specialised surgical services which are not available locally, they may be contemplating a much longer journey after day surgery. It is common to limit the recommended travelling time to an hour or less, but longer journeys are more common in countries with widely scattered populations. In Norway, for example, patients may often travel up to 300 miles by air or four to six hours by road.13 The available evidence suggests that travelling long distances is safe, provided that emergency care is available at the final destination. The patient must also be aware that the journey may be somewhat unpleasant, due to residual discomfort from the surgery and the possibility of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV).

Medical selection criteria

It is tempting to apply various criteria and cut-offs to day surgery selection, and such an approach has certainly been practised in the past.14 However, most limits of this type are somewhat arbitrary and rarely supported by sound evidence. In addition, there will always be patients who fall outside the exclusion criteria in whom day surgery would be both desirable and safe, while others might be unsuitable only through an interaction of several variables, none of which alone would be a contra-indication.

The modern approach7,8 is to consider the patient as a whole and assess their suitability according to their physiological status and overall fitness, rather than relying on arbitrary limits, such as age, ASA status or BMI. The interaction between the patient and the proposed surgery, as well as the intended anaesthetic and analgesic techniques, are also important in reaching a final decision.

ASA status

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification is a useful ‘shorthand’ for describing chronic health and is a good example of an arbitrary limit. It has previously been common to exclude patients graded ASA 3 and above from day surgery. Certainly, patients of ASA 3 do experience more complications during the intraoperative period than those of ASA grades 1 and 215 but, crucially, once these have been effectively managed, problems are no more likely in the medium-to-late recovery period. Furthermore, complications and the need to seek assistance from primary care are no more common in ASA 3 patients after discharge from day surgery.16 ASA 4 patients have a condition which represents a constant threat to life, yet a small number may still be suitable for some surgery on a day case basis under very specific circumstances, especially if the procedure can be performed under local or regional anaesthesia. In all cases, the specific condition(s) should always be assessed on an individual basis and specialist anaesthetic advice is advisable.

Obesity

Obese patients present numerous problems with manual handling, venous access, airway management, pulmonary ventilation, surgical access and so on, but none of these difficulties should preclude day surgery, since they would be equally problematic with inpatient management. Problems which would be directly relevant to day surgery include delayed respiratory depression or airway obstruction, poor pain management and delayed wound healing, but none of these problems begin to occur until the body mass index (BMI) is well in excess of 40kg/m2. Yet many far less obese patients have previously been denied day surgery, a good example of not considering the nature and timing of complications, only their overall incidence.

Patients with a BMI of up to 35kg/m2 should always be acceptable for day surgery (in the absence of other problems), while patients with a BMI of 35–40kg/m2 should be acceptable for most procedures.7 Even greater degrees of obesity are acceptable in some countries17 and many feel that obesity should not be an absolute contra-indication, provided the right level of expertise and facilities are available.8 Increasing numbers of obese patients are now safely undergoing day surgery and even gastric banding procedures for the morbidly obese have been performed as day cases.18

Day surgery – associated with short-acting medications, excellent pain relief achieved with non-opioid analgesia and early ambulation – offers clear benefits for obese patients who may be at particular risk in the hospital environment. However, obesity is also commonly associated with sleep apnoea, cardiac dysfunction and overall poor fitness, conditions which may independently make day surgery unsafe.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes is associated with end-organ disease in the cardiovascular, renal and autonomic systems and preassessment should carefully screen for evidence of these by way of a careful history, blood tests and ECG. Any abnormalities should be investigated and managed in their own right.

Preassessment should also consider the stability of diabetic control as poor glycaemic control increases the chances of wound infection and the likelihood of perioperative hyper- or hypoglycaemia, all of which are undesirable in day surgery. While random blood sugars are unhelpful, records of recent blood and urinalysis results are more informative and glycosylated haemoglobin provides evidence of stability over the past few months.

Perioperative glycaemic control is remarkably simple in stable diabetic day case patients, who are best managed in a way that interferes as little as possible with their usual regimen (see Figure 14.2). Normal medications (including metformin) should be continued up to, and including, the night before surgery,19 which should be scheduled first on the morning operating list. Patients should omit their morning oral hypoglycaemic agent or insulin and aim to resume normal diet and medication as soon as possible after surgery.20 The success of this strategy is most likely after relatively short procedures. Local or regional anaesthesia are preferable, but general anaesthesia is possible, provided a technique associated with minimal postoperative sedation, nausea and vomiting is used; multimodal anti-emetics may also be required. This approach can be adapted for afternoon surgery by allowing a light breakfast and morning short-acting hypoglycaemic therapy, but there is less time available to ensure a full return to normal and to manage unexpected difficulties. Therefore, diabetic patients should be managed during morning sessions whenever possible. Sliding scales and other complex regimens are unnecessary, and have no advantages, for stable patients undergoing relatively minor surgery, but may be required for more complex cases or when a simple regimen has failed, for example due to prolonged nausea.

Figure 14.2 Key principles for the management of diabetic day case patients

Figure 14.2 Key principles for the management of diabetic day case patients

reproduced from BADS (2005),33 with permission

Minor surgery in the morning

(In this context, a minor surgical procedure is defined as one where the patient is expected to resume oral intake within an hour or so of surgery)

Consider reducing long-acting insulin (insulatard, monotard, humulin I, ultratard or hypurin lente) taken before bed by 1/3 on night before surgery.

Omit morning insulin and/or oral hypoglycaemics.

On arrival in day surgery unit

Blood glucose <5mmol/l: Notify anaesthetist.

Patients on insulin or sulphonylurea: Consider infusion of 5% glucose at 100ml/hr and monitor blood glucose hourly.

Blood glucose 5–13mmol/l: Monitor only.

Blood glucose >13mmol/l: Check for intercurrent infection. Consider postponing surgery.

After surgery

Give delayed breakfast with usual morning insulin/oral hypoglycaemics.

Blood glucose should be in range 5–13 mmol/l prior to discharge.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree