Prehospital and Air Medical Care

Francis X. Guyette

David C. Cone

I. Trauma Triage

Trauma triage sorts patients on the basis of the severity of their injuries and the availability of resources. Generally, there are different types of prehospital trauma triage.

Field triage involves determining, prior to transport, if a trauma patient requires the services of a trauma center. Field triage uses an estimation of the severity of injury. Trauma triage criteria are used in single-patient events and events with small numbers of patients that do not exceed the capabilities of the local trauma system.

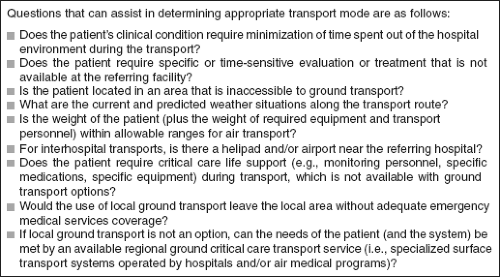

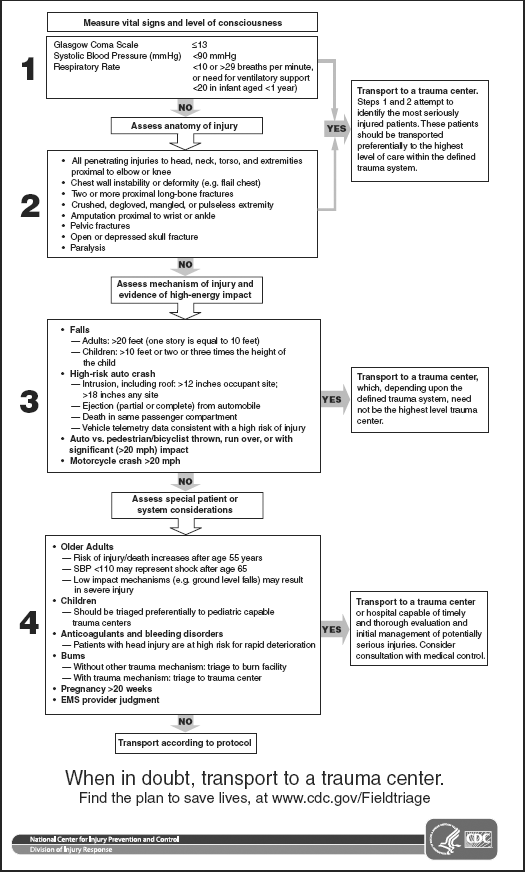

Field triage guidelines. Knowledge of injury, mechanism, and existing co-morbid factors are keys to optimal trauma triage. Unfortunately, no single factor will guarantee triage success. The following have been developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Table 9-1):

Patient assessment. The initial patient survey identifies and treats immediately life-threatening injuries.

Abnormal vital/physiologic signs suggest the need for rapid treatment and transport to the highest level of care within a trauma system.

Anatomic locations and types of injuries can predict the need for emergent surgical or specialty care.

Mechanism of injury. Mechanistic criteria enhance the sensitivity of the guidelines by considering the forces involved at the scene and the kinetic energy transferred during the event. The mechanism is not as strong a predictor of need for emergent operation or intensive care compared to the anatomic and physiologic criteria. Prehospital personnel should review the case with the direct medical oversight (DMO) physician by phone or radio to choose a destination.

Premorbid conditions. No formal system exists for assessing or ranking premorbid conditions; yet these are often included in decision-making. Some such as pregnancy, age, and anticoagulation may alter the disposition of the patient to a specialty center. As with mechanism of injury criteria, discussion with the DMO physician may be helpful.

Field triage scoring. Several trauma-scoring techniques determine the severity of injury of trauma victims both in the hospital and in the field. Examples include the Trauma Score, CRAMS Scale, Prehospital Index, and Trauma Triage Rule. Accurate trauma scoring is dependent on diagnostic skills and the availability of adjunctive testing, and is limited by field conditions, patient intoxication, and compensatory physiologic mechanisms masking major injuries. Trauma-scoring systems typically look at combinations of the following:

Cardiovascular system

Respiratory system

Central nervous system

Type and location of injury

Abdominal examination

Prehospital triage for air medical transport

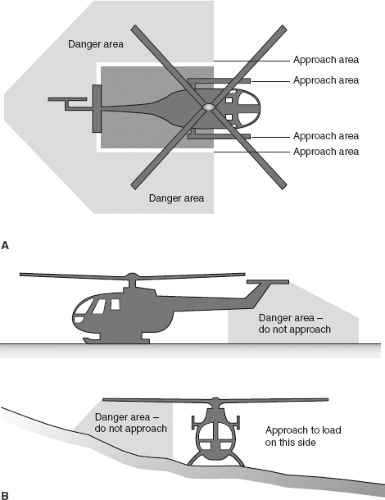

The transport of trauma patients directly from the scene should be supported by DMO or pre-approved protocols on the basis of the factors of time, distance, geography, patient stability, and local resources. Air medical transport may reduce blunt trauma mortality rates compared with ground transport. Undue

delay of transport from the scene to the closest hospital while waiting for a helicopter should be avoided. Rendezvous at the hospital’s helipad (helistop) allows for a more efficient use of time and provides additional options should the patient decompensate.

The National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP) and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) have recommended triage guidelines for air medical dispatch (Fig. 9-1).

Interhospital transport of trauma patients usually involves moving a patient to a facility with a higher level of care.

Weather, geography, logistics, or other factors determine flight suitability. The final decision to accept the mission rests solely with the pilot, however any member of the crew should have the right to abort the mission. Crew safety is paramount.

Table 9-1 2011 Guidelines for Field Triage of Injured Patients

Mass casualty triage involves prioritizing patients when needs exceed available resources. The goal is to provide the most benefit to the greatest number of patients. This requires identifying potentially salvageable patients with life-threatening conditions who require immediate treatment and transport.

The first EMS personnel to arrive on scene initiate mass casualty triage. Providers first ensure scene safety and relay basic information regarding the incident to dispatchers, so additional resources can be mobilized and hazards mitigated. The responsibility for patient triage is assigned to more experienced personnel when they arrive. Field triage works best when victims are limited to a small geographic area. Large disaster sites (such as earthquakes and floods) or disasters with geographically distinct areas (such as either side of a train crash, when mobility between and access to the two sides is limited by the wreckage) can require multiple triage sites.

Principles. While it is generally taught that the most critically injured patients are transported first, empiric data are lacking to support this principle. Triage is a continuous process, with frequent reassessment of patient status and resources. Patients are typically re-triaged on arrival at the hospital.

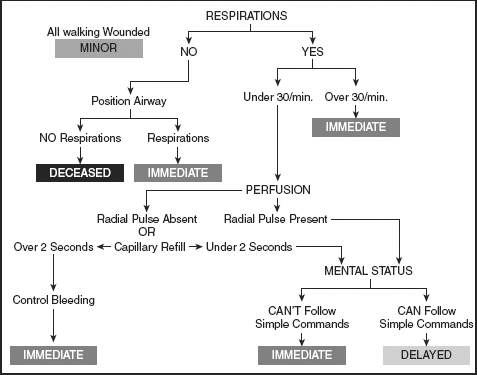

Simple triage and rapid treatment (START) is the most commonly used mass casualty triage system in the United States. Patients who are ambulatory are first removed from the area. Next, patients are classified as “expectant” if obviously dead or if not breathing after one attempt to reposition the airway. Remaining patients are categorized as “immediate” or “delayed,” on the basis of the evaluation of respiratory rate, perfusion, and mental status. An abnormality

in any one parameter places the victim in the “immediate” category (Table 9-2).

Table 9-2 START Triage Guidelines

Triage tags are often used to identify needs in both large and small multi-victim incidents.

Problems that can occur with triage tags include:

Separation of the tag from the victim

Contamination by blood or body fluids

Limited space for documentation

Inability to “upgrade” a patient’s triage category, since many tags use color-coded strips that are torn off (leaving the patient’s categorization attached) and cannot be reattached if a patient’s status worsens

Color codes are traditionally used to identify patient categorization by injury severity and need for transport:

Red “immediate” or the most critically injured. This includes patients with major injuries to the head, thorax, and abdomen for which immediate surgical or specialty care is required.

Yellow “delayed” or less critically injured. This includes patients who are less seriously injured, who still likely require in-hospital treatment, but whose clinical condition permits a delay of several hours without endangering life.

Green “ambulatory” with no life- or limb-threatening injury identified. Ideally, medical personnel will reassess all of the ambulatory patients who are initially moved away from the disaster scene, to identify injuries.

Black “expectant” or dead. Patients who would be triaged to “red” under certain circumstances might be triaged to “black” when resources are limited.

Limitations to triage. Patient injuries and conditions are dynamic and assessment is limited, making perfect triage difficult to achieve. In both field triage and mass casualty events, over- and under-triage may occur.

Over-triage (false positives) occurs when a patient who does not require a trauma center or high level of immediate care is assigned to and transported to a trauma center. When resources are not constrained, this results in some degree of wasted resources if activation of the trauma team occurs unnecessarily. In a mass casualty situation, over-triage may limit the ability of a trauma center to provide optimal care for those who need it.

Under-triage (false negatives) occurs when a patient who may benefit from trauma center/higher level of care is transported to a setting with fewer resources. This can affect ultimate outcomes; in a mass casualty incident, under-triage may be unavoidable as trauma centers become saturated.

While it is commonly stated that 50% over-triage is acceptable to achieve 10% under-triage, there are no outcome data to support this supposition.

II. Traumatic Arrest

The term “traumatic arrest” refers to the end result of a variety of pathologic processes in response to injury and is not a single clinical entity.

Etiology. EMS personnel should be trained to recognize the most common treatable causes of traumatic cardiopulmonary collapse in the prehospital setting: Airway obstruction, hypoventilation or hypoxemia, tension pneumothorax, and uncontrolled hemorrhage. These etiologies are well covered elsewhere. Airway loss or failure remains the most common reversible cause, followed by hemorrhage/volume loss.

Determination of viability

Likelihood of survival. The research on this topic often includes a mixture of clinical conditions, making interpretation difficult. A few general guidelines can be gleaned from the available data.

Victims of penetrating trauma have a greater likelihood of survival from cardiac arrest than victims of blunt trauma.

Survival from arrest is more likely after stab wounds than after gunshot wounds.

Arrest before EMS arrival decreases the likelihood of survival, particularly if transport times are long.

Presence of recognized and quickly treated tension pneumothorax or pericardial tamponade is a positive prognostic factor, but this is usually not done in the field.

Victims of blunt trauma who suffer cardiopulmonary arrest have an extremely low likelihood of survival, approaching zero (unless witnessed and treated in the emergency department).

Those found by prehospital personnel to be in arrest with no signs of life (absence of spontaneous movement or respirations, and absence of reflexes including pupillary) and no electrical activity on the electrocardiogram have a negligible chance of survival. Prehospital resuscitation is not indicated for these patients.

The presence of some life sign (eye movement, pupil reaction, corneal reflex, organized cardiac rhythm) in pulseless, nonbreathing patients confers a low likelihood of survival. Because aggressive interventions (e.g., intubation, ventilation, release of tension pneumothorax, and volume resuscitation) result in occasional long-term survival, resuscitation is attempted. Persistence of pulselessness on hospital arrival is uniformly fatal and further resuscitation is not warranted.

Deterioration into cardiac arrest after EMS arrival but before hospital arrival also has dismal prognosis, but full resuscitative efforts should generally be undertaken. Most data suggest no benefit to emergency department thoracotomy for prehospital blunt traumatic arrest.

Criteria for attempting resuscitation. Resuscitation should be attempted on patients in arrest caused by major blunt or penetrating trauma, unless one or more of the following criteria are met:

Injury obviously incompatible with life (e.g., decapitation, incineration)

Absent signs of life (no respiratory effort, no pupillary response or eye movement, no response to deep pain) and ECG rhythm of asystole

Documented, untreated pulselessness and apnea for 15 minutes (e.g., prolonged entrapment, hazardous scene) in a normothermic patient

Rigor mortis or dependent lividity

Transport time to an ED or trauma center of more than 15 minutes after the onset of cardiopulmonary arrest

Special conditions

Electrical shocks or lightning. Since arrest is usually caused by a cardiac dysrhythmia and may be reversible, aggressive resuscitation should be attempted. In cases of multiple casualties from an electrical incident, defibrillation of those in ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia arrest should be given first priority.

Drowning or hanging. Arrest is usually caused by asphyxia in these situations. Although appropriate trauma care, such as spinal immobilization, should be instituted, the decision to resuscitate can be based on criteria for “medical” arrests. Hypothermia should be considered in drowning victims.

Hypothermia. The presence of hypothermia (core temperature below 35°C) can result from or lead to a traumatic event. Hypothermia can make it difficult to detect signs of life. Patients who are severely hypothermic should generally undergo active core rewarming before cessation of resuscitative efforts unless injuries are clearly incompatible with life. Refer to Chapter 43 for more details on this illness and treatment.

Arrest secondary to medical cause. It can be a challenge to recognize patients who may have suffered trauma or cardiac arrest because of a medical condition, such as the driver of an automobile who develops ventricular fibrillation with a resultant crash. Unless evidence suggests a fatal injury, a patient whose mechanism of injury does not correlate with the clinical condition should typically undergo resuscitative efforts similar to any other non-traumatic arrest patient. Following return of spontaneous circulation, these patients should undergo a complete trauma evaluation to exclude further injury followed by treatment of the medical condition that precipitated the arrest.

Management of traumatic arrest

At the scene. Time on scene (excluding extrication) should be as short as possible—often targeted for 10 minutes maximum, absent extrication concerns or other operational delays.

Ensure scene safety before entry, particularly in cases involving assaults, fire, hazardous materials, confined spaces, and vehicular traffic. Law enforcement or fire service assistance may be needed to secure the scene prior to EMS operations. Field personnel should not put themselves at risk for a patient with a negligible chance of survival.

Recognize cardiac arrest

Determine whether to initiate resuscitation (see Section B).

Assess for the presence of special conditions such as hypothermia or a primary medical cause that might influence decision or course of resuscitation.

Start manual and device-based spinal immobilization

Perform chest compressions at a rate of 100/minute

Open airway using jaw thrust without head tilt. Inspect oral cavity, and suction or manually remove debris (blood, teeth, etc.).

Ventilate patient with basic techniques (e.g., bag-valve-mask) at a rate of 10 to 12 breaths/minute. Use supplemental oxygen to maintain oxygen saturations >95%.

Control severe external hemorrhage

Determine ECG rhythm (note that above steps may be carried out while assessing rhythm to decide whether to proceed with resuscitation):

Defibrillate for ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia.

An organized rhythm (pulseless electrical activity) confers a greater likelihood of a reversible condition.

Manage the airway (refer to Chapter 11); this starts with supplemental oxygen in all.

If able to intubate or place a supraglottic airway (Fig. 9-3), confirm proper tube position and carefully secure tube.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree