Injury Prevention

Charles C. Branas

I. Introduction

Worldwide, injury is the leading cause of death for the first half of the human life span and a regular source of disability and disfigurement. Every day in the United States, hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children are injured severely enough to seek medical care. Hundreds of these people will sustain a long-term disability due to their injuries and additional hundreds will die.

Injury is among the top three causes of death in the United States. The combined burden of unintentional injury deaths, suicides, and homicides was the leading cause of death in those from 1 to 44 years of age. Unintentional injury alone is the fifth leading cause of death for all US age groups. In 2007, over 180,000 injury-related deaths were documented in the United States. The top five mechanisms of injury deaths in the United States were road traffic, poisonings, firearms, falls, and suffocation.

Around the world, injuries, mainly from motor vehicles and weapons, are rapidly becoming the number one global health threat to children, young adults, and developing nations. In any given year about one out of every three people will be injured severely enough to seek medical care. Injuries thus affect people from all walks of life but are very disproportionately experienced by the poor, creating one of the greatest sources of global health inequity between developed and developing countries. Injuries are the largest contributor to disability in low and lower-middle income countries. People who die from injuries are, on average, more than 30 years younger than people who die from other leading causes. They are children, workers, and young parents, society’s most valued and economically productive members.

Over 90% of the world’s injury deaths occur in low and middle income countries and injury deaths per capita are three times higher in low as opposed to high income countries. Road traffic deaths are predicted to increase by 83% in low and middle income countries but to drop in high income countries by 27% as soon as 2020. Road traffic crashes are the leading cause of death globally for 10 to 24 year olds. Moreover, for every death due to war, there are three deaths due to homicide and five due to suicide. Yet these same injuries are highly underappreciated as a global health threat and receive inadequate attention and funding. Because injuries so heavily affect individuals in their most productive years, their continued growth is sure to hamper or wipe away economic gains in many developing nations and further health inequities between developed and developing nations.

Mortality alone does not characterize adequately the profound physical, psychosocial, and economic effects of injury. Over one-third of all US emergency department visits, almost 40 million in total, are related to injury. The most common injuries were from falls, nonvehicular strikes (such as assaults), and road traffic. It is estimated that nearly 1 in 6 Americans will require treatment for injuries and over 2 million Americans will be hospitalized for injuries each year. In 2005, total injury-attributable medical costs were estimated to be over $77 billion, or about 5% of all medical costs in the United States. The estimated total cost of injury in the United States in 2005, based on direct medical care and work losses, was estimated at just over $355 billion.

Physicians typically focus on the resuscitation and definitive treatment of injuries. However, recognizing the immense societal burden of injury, and the fact that as much as one-half of all injury deaths take place at the scene of the injury or within minutes of the event itself, necessitates expansion of the medical mission to include prevention of injury before it occurs.

II. Understanding Injury Prevention

Injury deserves attention as a leading cause of death and disability around the world. Injury also deserves attention because it occurs as part of a unique disease process: Violence, suicide attempts, falls, and traffic crashes are all disease-generating events that can suddenly kill or disable otherwise healthy people. This is in contrast to other leading diseases, which generally become noticeable after months or years of risk exposure and have relatively slow pathophysiologic processes. Thus, injury develops in a fraction of a second, often after a similarly sudden exposure to one or more risk factors, making its study and prevention especially challenging.

Injury occurs across a timeline or continuum: From early precursors to the defining disease event to immediate and long-term consequences. Opportunities to prevent or ameliorate injury correspondingly differ across this continuum: Primary prevention seeks to completely avert injuries by altering susceptibility or reducing exposure; secondary prevention employs early detection and prompt treatment of injuries once they occur; and tertiary prevention focuses on limiting disability and restoring function for injured individuals.

Although the medical system is rooted in secondary and tertiary prevention, primary prevention is a potentially more efficient way to relieve the burden of injury. Thus, prevention of all types of injuries is a priority and an expectation of personnel in hospitals, both trauma centers and those that are not. The Committee on Trauma (COT) of the American College of Surgeons mandates that trauma center personnel educate the public about injury as a major public health problem. Physicians are natural leaders in expanding trauma care to include the primary prevention of injury. The COT also suggests that physicians move beyond just public education to activities that include surveillance, epidemiology, intervention research, and evaluation of prevention program effectiveness.

III. The Science of Injury Prevention

The science of injury prevention has its roots in many fields including medicine, public health, criminology, engineering, and others. Among the earliest attempts to systematize the approach to injury prevention was put forth by Dr. William Haddon several decades ago in the form of 10 injury countermeasures:

Prevent the creation of the hazard in the first place.

Reduce the amount of the hazard brought into being.

Prevent the release of the hazard that already exists.

Modify the release of the hazard that already exists.

Separate, in time and space, the hazard and that which is to be protected.

Separate, by material barrier, the hazard and that which is to be protected.

Modify the relevant basic qualities of the hazard.

Make that to be protected more resistant to damage from the hazard.

Counter damage already done by the hazard.

Stabilize, repair, and rehabilitate the object of the hazard.

To the prevention strategist, these countermeasures give basic guidance on when to intervene, what to intervene on, and how to intervene. More important, they offer a system whereby the prevention strategist would leave no stone unturned. That is, by considering all 10 countermeasures, he or she can ensure that no potentially promising or effective intervention is overlooked.

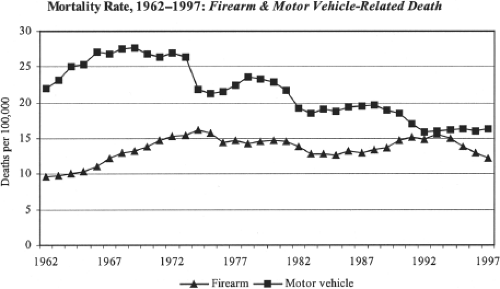

Knowledge of successful strategies to reduce the burden of specific injuries has increased. The decline in incidence of motor vehicle injuries is a case in point. Although motor vehicle injuries continue to be the leading cause of injury death in the United States, their rates have declined considerably over the past 25 years (Fig. 19-1). This decrease is the result of systematic and multifaceted prevention efforts that include the implementation of adequate surveillance systems (for instance, the Fatality Analysis Reporting System at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration), the enforcement of government regulations (such as through updated Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards), the introduction of active (such as seat belts) and passive (such as airbags) safety devices, improved roadway design (such as left-turn

jughandles), advocacy for shifts in social norms (such intolerance of drunk driving), and improved trauma care systems.

Figure 19-1. Firearm and motor vehicle–related death rates. (From National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with permission.)

This success has, however, not extended to all mechanisms of injury, as can be seen in the concurrent increase in firearm injury fatality during the same time period that motor vehicle injury fatalities decreased (Fig. 19-1). Nevertheless, the successful injury prevention strategies used in reducing motor vehicle injuries can also be used to address other major injuries such as those related to firearms and falls. To ensure a high probability of success, these prevention strategies should always be multifaceted, essentially diversifying the prevention strategist’s portfolio to defend against failure in any one particular intervention. Moreover, injury prevention strategists should always proceed scientifically, under the mantle of sound evidence, and with the understanding that injuries are not random events. The science of injury deterrence is best founded on epidemiologic surveillance followed by the implementation of prevention strategies that have been thoughtfully designed and systematically evaluated. The following four steps can be taken to more fully understand the epidemiology of specific injuries and mount prevention strategies:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree