CHAPTER 10 PREHOSPITAL AIRWAY MANAGEMENT: INTUBATION, DEVICES, AND CONTROVERSIES

Prehospital trauma airway management is probably the biggest challenge faced by prehospital providers. These professionals must not only acquire but also maintain essential skills to adequately manage airway problems at the scene and during transport of trauma victims to trauma centers.

WHO NEEDS AN AIRWAY?

In trauma, it has been shown that moribund patients would benefit from an airway, particularly those who are candidates for a resuscitative thoracotomy upon arrival at the hospital.1

DIFFICULT AIRWAY

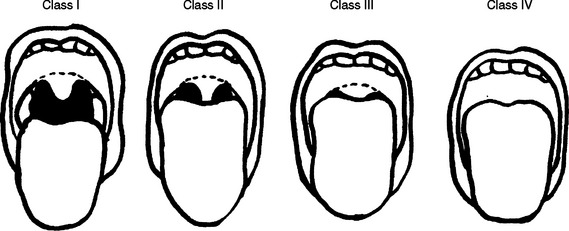

The Mallampati classification has been used for many years by anesthesiologists during preoperative evaluations for the identification of a difficult airway and to predict difficult intubation2 (Figure 1). It compares tongue size with the oropharyngeal space, and its reliability has been questioned because it does not take into account other factors that may make intubation difficult or impossible in the prehospital setting. However, if the patient is still able to follow simple commands, direct visualization of the oropharynx by asking the patient to open the mouth will give additional and important information to the astute prehospital provider. Rich3 described the 6-D methods of airway assessment: disproportion; distortion; decreased thyromental distance; decreased interincisor gap; decreased range of motion in any or all of the joints—atlanto-occipital, temporomandibular, and cervical spine, always present in trauma; and dental overbite.

Figure 1 Difficult airway—the Mallampati score modified by Samsoon and Young.

(From Mallampati SR, et al: A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J 32:429–435, 1985.)

WHICH STRATEGY SHOULD BE USED?

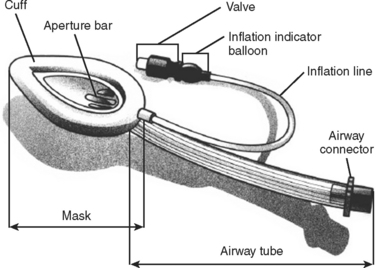

Laryngeal Mask Airway

The LMA is one alternative to endotracheal intubation (Figure 2). Its use is particularly important in patients with difficult airways (defined later) and in patients treated in “unfriendly” environments (rain, dark, prolonged extrication, etc.). It also can be used as a rescue strategy following a failed RSI. Additionally, it can be used to facilitate intubation, which is obtained by passing the endotracheal tube through the LMA.

The insertion of the LMA is done blindly into the oropharynx, and it is usually tolerated without the need of neuromuscular blockade. The LMA lies in the hypopharynx in the supraglottic position. The successful placement of the LMA is independent of the Mallampati score, presence of a C-collar, or in-line immobilization of the neck. Spontaneous ventilation through the LMA is possible, and manual ventilation through the LMA is superior to bag-valve-mask ventilation, because the latter requires two hands to maintain a good seal. Studies comparing the success rates have shown that paramedics achieve higher levels of successful placement with the LMA compared to endotracheal intubation.4 The LMA may be particularly useful in patients with a difficult airway, since direct visualization of the cords is not required and neuromuscular blocking agents are not necessary. The advantages of the LMA over the Combitube (described next) include lower risk of malpositioning, no risk of esophageal intubation, and less trauma to the oropharynx. A major disadvantage of the LMA is that it does not protect against aspiration, which may carry significant risk in patients with intact airway reflexes. Another limitation of LMA is related to the difficulty in generating high airway pressures, which may lead to ineffective ventilation.5

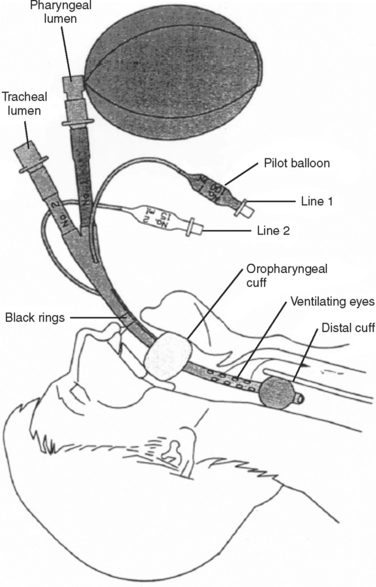

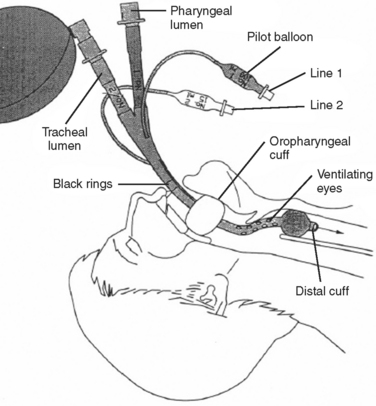

Combitube

The Combitube consists of a device with two lumens. One of the lumens has an open distal end similar to an endotracheal tube, whereas the other lumen has a closed distal end, with several holes proximal to its balloon cuff. A second balloon of higher volume is located more proximally to the side holes, and it is used to secure the tube in position. The Combitube is inserted blindly and allows ventilation through either lumen. Following blind insertion, the distal tip is usually located in the esophagus. After inflating the oropharyngeal balloon, the esophageal cuff is inflated. Attempts to ventilate through the pharyngeal lumen will determine whether the distal tip is in the esophagus or trachea. If there is no change in the colorimetric, end-tidal carbon dioxide detector, or if breath sounds are absent, then the distal tip is in the trachea and the patient should be ventilated through the tracheal lumen (Figures 3 and 4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree