Postpartum Breast Complications | 29 |

Women commonly present to the obstetric triage/emergency department during the postpartum period with breastfeeding concerns and complications. Breastfeeding has become increasingly popular secondary to worldwide research that has consistently demonstrated significant benefits to both infant and mother. Whereas only 24.7% of women in the United States initiated breastfeeding in 1971, 79% did so in 2011, 49% continued for at least 6 months, and 27% were still breastfeeding 1 year postpartum (American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2016).

The most common difficulties encountered by breastfeeding women are generalized engorgement of the breasts, plugged ducts, and nipple trauma. These conditions generally respond well to supportive care and continued attempts at feeding, and will be discussed briefly at the beginning of this chapter. Postpartum inflammatory breast disease, including puerperal, or lactational, mastitis and breast abscess are less common. It has been estimated that up to 33% of breastfeeding women experience mastitis (Jahanfar, Ng, & Teng, 2013), while only 0.1% (Kvist & Rydhstroem, 2005) to 0.4% (Amir, Forster, McLachlan, & Lumley, 2004) develop abscesses. These latter disorders are infectious in nature and require more intensive treatment, including antibiotics and possible surgery. They will be the topic of the remainder of the chapter.

COMMON BREASTFEEDING DIFFICULTIES

Engorgement and Plugged Ducts

Breast engorgement is the swelling of the breasts resulting from incomplete emptying of milk. Early engorgement occurs with the onset of increased milk production that characterizes the first few days postpartum, when the breasts swell secondary to edema and inflammation in addition to milk accumulation. The lactating mother will commonly report distinct tenderness, firmness, and warmth of the breasts. These findings are usually bilateral and generalized, and erythema tends to be absent. Late engorgement is generally due to milk stasis alone and can be either localized or generalized, though swelling is often not as pronounced. It is uncommon for women with either type of engorgement to report systemic symptoms such as fever or malaise. Both types are generally attributable to incorrect or inconsistent breastfeeding technique, prohibiting efficient drainage of milk from the breasts.

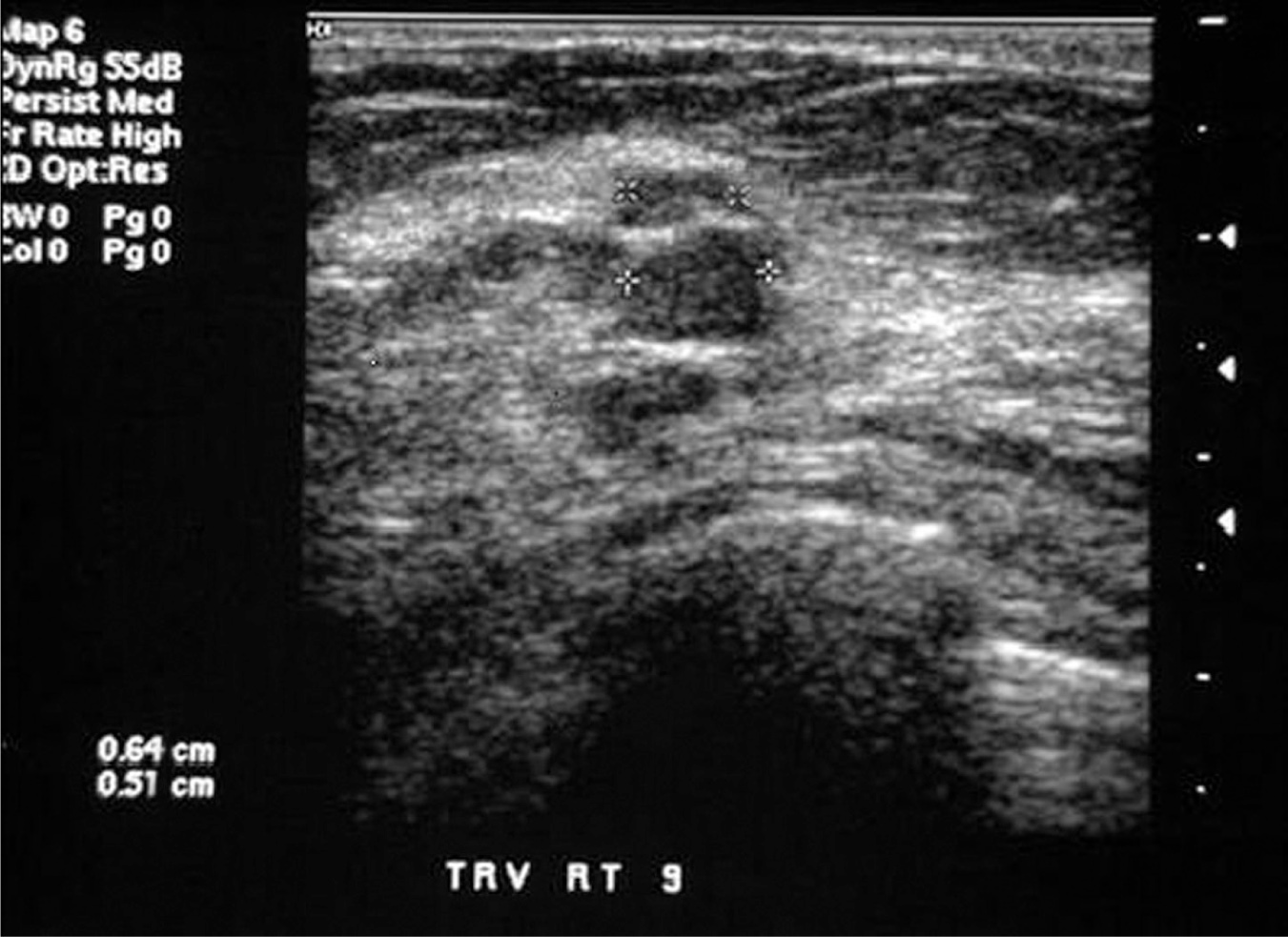

Plugged ducts are also commonly seen in women who report suboptimal breastfeeding technique, or who have increased milk supply relative to demand 346due to a change in feeding frequency or intensity. Localized distension of breast tissue occurs as a result of inadequate drainage in a single duct, and can be palpable by the breastfeeding woman as a distinct, tender mass. As with engorgement, systemic symptoms are absent. If unrelieved, a galactocele, or milk retention cyst, may form. Though these are full of milk initially, the contents can become thicker over time. Tenderness usually resolves as well. A soft cystic mass, with no evidence of infection, is often the sole finding on clinical examination. Ultrasound imaging of a galactocele may show a well-defined mass with internal complexity, as shown in Figure 29.1.

The key to the management of generalized engorgement without infection as well as plugged ducts is prevention. This is best accomplished by frequent emptying of the breast, and is most efficiently achieved by breastfeeding the infant directly. A satisfactory latch-on is essential, which proves difficult for many nursing women to establish. Proper positioning of the infant, consistency in feeding techniques, and an environment that is conducive to breastfeeding are all instrumental in allowing the infant to latch-on successfully. Lactation consultants can be called upon when needed to advise and demonstrate to women how best to optimize these factors.

If the latch-on is not sufficient for relief of engorgement or a plugged duct, the use of a breast pump to drain the breasts is recommended. Manual expression and massage can also be helpful. While cold compresses are preferred to address the swelling that accompanies early engorgement, heat is more useful in cases of late engorgement and plugged ducts, both for symptom relief and to encourage milk flow. Galactoceles may resolve spontaneously or may be treated with aspiration or surgical removal.

Of note, a very recent randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial suggests that efforts to prevent infectious mastitis may begin during pregnancy as well. Significantly lower rates were found in women who received an oral probiotic during the third trimester of pregnancy, 25% versus 57% with mastitis in the placebo group (Fernandez et al., 2016). In addition, the bacterial counts in the milk of women who had been given the probiotic but still developed mastitis were significantly lower than the counts for the women with mastitis in the placebo group.

Figure 29.1 Ultrasound appearance of a galactocele

Source: Courtesy of the Department of Radiology, Women & Infants Hospital, Providence, RI.

TABLE 29.1 Lactation Resources

RESOURCE | WEBSITE |

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine | |

Baby Friendly USA | |

La Leche League | |

National Association of Professional and Peer Lactation Supporters | |

Medications and Mother’s Milk | |

US Breastfeeding | |

US Lactation Consultant Association |

Source: Briggs et al. (2011).

Nipple Trauma

Nipple trauma, including abrasions, cracking, blistering, or bruising, can be the cause or result of a poor latch-on, thereby discouraging ongoing efforts to breastfeed. The best preventative measure is proper positioning of the infant to ensure optimal latch-on. When this is complicated by an anatomic abnormality of the woman’s nipples or the infant’s mouth, a lactation consultation is recommended.

Once present, various treatments are available that can be used to decrease soreness and heal traumatized nipples. These include purified lanolin ointments, hydrogel dressings, or the combination of antibiotic, antifungal, and mild steroid therapy known as “all-purpose nipple ointment.” In addition, breast shields may be utilized to prevent friction to nipples between feedings as needed. Since infections of the skin and breast, most commonly with Candida albicans or Staphylococcus aureus (see the following text), occur more frequently in women with injured nipples (Lawrence & Lawrence, 2015), it is crucial to address nipple trauma early in its course.

Resources

Women presenting with the previous general breastfeeding difficulties may be experiencing a great deal of distress and anxiety. The ability to provide information and guidance to these nursing mothers can help to reassure them that such challenges are not uncommon, and encourage them to continue breastfeeding. Some popular resources are listed in Table 29.1, and can assist in providing lactation support or verifying the compatibility of a certain recommended treatment with breastfeeding.

POSTPARTUM INFLAMMATORY BREAST DISEASE

The term “postpartum inflammatory breast disease” includes both lactational mastitis and breast abscesses. Mastitis is caused when bacteria, commonly skin flora and/or oral flora from the infant, have access to stagnant milk in the 348breast, generally via the nipple. If left untreated, the infection may progress to abscess formation, which is estimated to occur approximately 3% to 11% of the time (Amir et al., 2004).

The most common etiologic organism in postpartum inflammatory breast disease is S. aureus and Staphylococcus albus (Jahanfar et al., 2013). Streptococcus pyogenes, E. coli, Bacteroides species, Coagulase negative staphylococci, Proteus, and Corynebacterium species are also found in some milk cultures. Candidal breast infections will be discussed separately in the Differential Diagnosis section. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is gaining increasing importance as a causative organism of mastitis as well as skin infections in general (Schoenfeld & McKay, 2010). Risk factors for the presence of MRSA include recent hospitalization, positive culture results confirming colonization by MRSA in the past (personal or close family member), chronic illness or nonhealing wounds, or failure of treatment directed toward methicillin-sensitive S. aureus. In one study of milk cultures from women who required hospitalization for treatment of mastitis, MRSA was the most common organism isolated; 44% (24 of 54) for women with mastitis alone, and 67% (18 of 27) in women with abscess formation (Reddy, Qi, Zembower, Noskin, & Bolon, 2007).

PRESENTING SYMPTOMATOLOGY

The most common complaints reported by a breastfeeding woman with mastitis include pain and tenderness in the affected breast. Warmth and/or redness of the breast and nipple discomfort, cracking, or excoriation are often noted as well. Fever and flu-like symptoms including malaise and myalgias are common. Axillary pain due to reactive swelling of the lymph nodes on the affected side may also occur. Finally, when a breast abscess is present, the breastfeeding woman may report the presence of a painful mass in the affected breast. Septic shock is rare.

HISTORY AND DATA COLLECTION

The postpartum woman with the previous symptoms will typically describe a history of difficulty with breastfeeding. Reports of poor milk production or a sensation of incomplete emptying of the affected breast are common, as is a history of prolonged engorgement, a blocked duct, or nipple trauma. Weaning may be in progress. Any factor that increases the likelihood that stagnant milk is present increases the risk of postpartum inflammatory breast disease. A prior episode of mastitis and/or breast abscess while breastfeeding either the current or a previous infant increases this risk as well.

A woman who presents with worsening symptoms despite standard treatment for mastitis is at increased risk for having either less common or resistant organisms such as MRSA present in the breast milk. A breast abscess is more likely under these circumstances as well. Breast abscesses are more frequently seen in primigravidas, women over the age of 30, and women who delivered at 41 or more weeks gestation (Kvist & Rydhstroem, 2005). Smokers, obese women, and African Americans are at higher risk of both lactational as well as nonlactational abscesses (Bharat, Gao, Aft, Gillanders, Eberlein, & Margenthaler, 2009).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Examination of the affected breast of a woman with postpartum inflammatory breast disease usually reveals erythema and swelling. Early in the course of 349the infection, subtle streaks of light pink in a single region of the breast may be the only visible abnormality. In later stages, a firm, red, swollen area of the breast, exquisitely tender to palpation or to ongoing attempts to breastfeed, may develop. Classically, these findings are limited to one region of the breast, extending from the nipple outward in a wedge-shaped pattern. However, either localized or generalized engorgement may be found as well. A fluctuant mass is often palpable when an abscess is present. Fever may be documented, and, if so, tachycardia may present as well. Hypotension is uncommon except in rare cases of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or sepsis related to an ongoing or inadequately treated infection.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

Lactational mastitis can be diagnosed by clinical examination alone, and empiric antibiotic therapy may be initiated without laboratory testing or culture results. If a complete blood count (CBC) is drawn, however, the white blood cell count may be elevated. Breast milk can and often should be cultured, especially with a severe or recurrent infection, or with one that is persistent despite prior antibiotic treatment. The results can then be used to tailor the ultimate antibiotic selection, since mixed flora, anaerobes, and Proteus are found more commonly in these cases (Bharat et al., 2009). Blood cultures are recommended only if the breastfeeding mother appears septic.

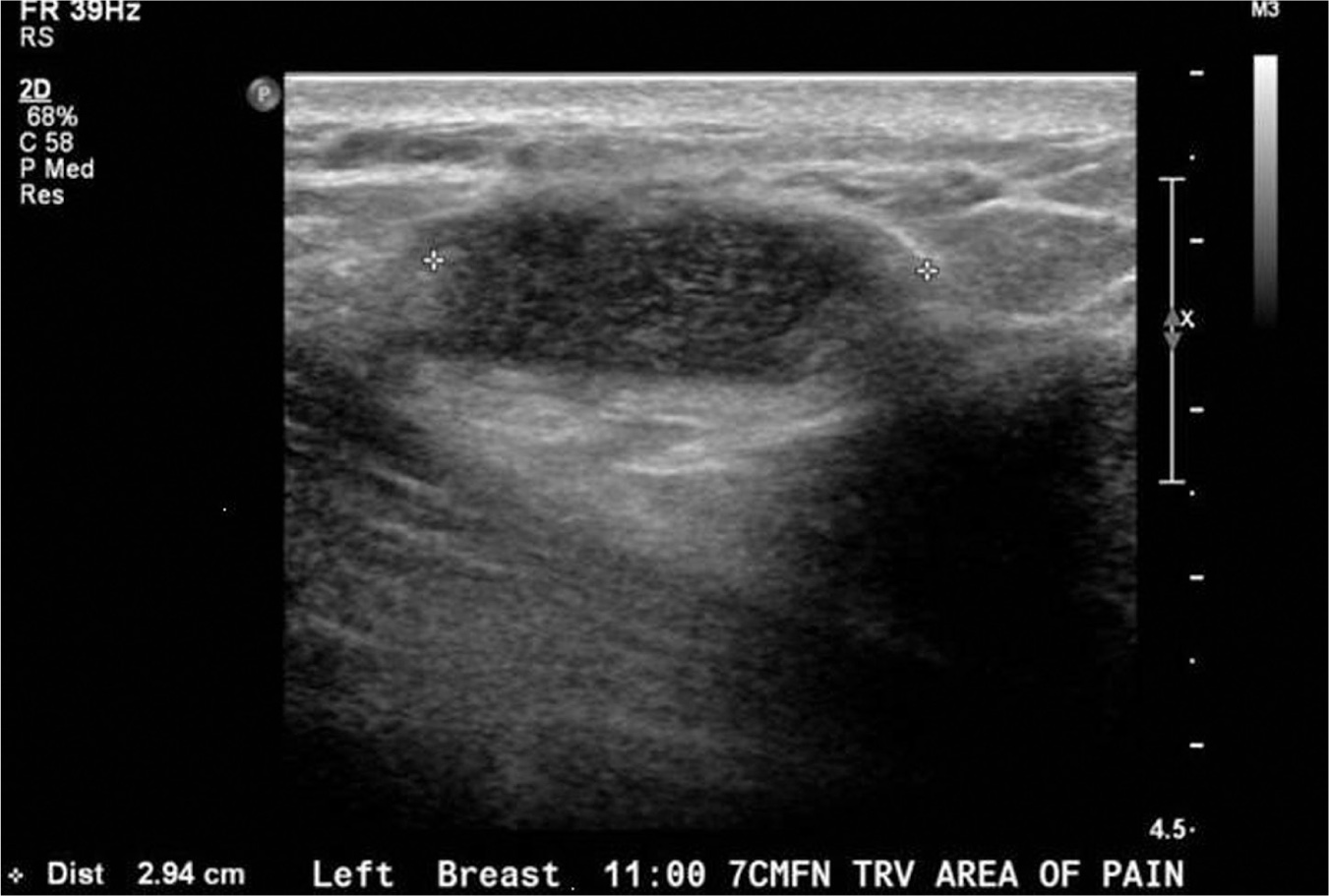

Imaging studies are not required for the diagnosis of lactational mastitis, nor are they necessary to make a diagnosis of a lactational abscess if a fluctuant mass is found on clinical breast exam. However, as will be discussed later in the chapter, ultrasound is often used to confirm an uncertain diagnosis, as well as to direct aspiration of a fluid collection. Figure 29.2 shows the typical appearance of a breast abscess on ultrasound.

Figure 29.2 Ultrasound appearance of breast abscess

Source: Courtesy of the Department of Radiology, Women & Infants Hospital, Providence, RI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree