Peripheral Vascular Injuries

Maria E. Moreira and Peter T. Pons

Prompt recognition and management of peripheral vascular injuries is crucial to limb salvage and preservation of function. A vascular injury should be suspected in any patient with a penetrating injury or a major fracture or dislocation secondary to blunt trauma. Penetrating trauma accounts for approximately 85% of vascular injuries in the United States; blunt trauma and iatrogenic causes are responsible for the rest.

Blunt trauma can cause spasm, external compression, mural contusion, intimal tear, thrombosis, or aneurysm formation. A high index of suspicion is necessary in these cases as injury can be very subtle in presentation. Stretching, tearing, or shearing forces can damage a vessel while leaving very little external injuries. The classic example is dislocation of the knee with associated popliteal artery injury in which there are very few visual clues to indicate vascular injury.

In penetrating trauma, the penetrating object can directly injure vascular structures when traversing the path of a vessel. Injuries can include partial or complete vessel transection, contusion, laceration, or arteriovenous fistula. The most commonly involved vessels are the brachial and axillary arteries in the upper extremity and the femoral and popliteal arteries in the lower extremity.

The emergency physician must obtain a complete history, perform a careful physical examination, and be aware of the mechanics that produce vascular injury, even if there are minimal or absent physical findings that suggest vessel damage.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Evaluation of extremity pulses distal to the injury is essential to the identification of vascular injuries. The following pulse findings are indicative of a vascular injury: diminished or absent pulses, thrill or bruit suggestive of an arteriovenous fistula, a pulsatile mass or rapidly expanding hematoma. Other etiologies for the pulse difference, such as shock should also be considered. Pulse differences due to shock should correct with resuscitation. The examiner must consider that the presence of a pulse does not completely exclude a vascular injury. Collateral circulation or transmitted pressure waves through a small clot or intimal flap can produce a distal pulse.

A Doppler can be used to further assess quality of pulses. The three levels of Doppler signal are monophasic, biphasic, and triphasic. Triphasic is the normal signal in an intact vessel. Changes in the signal can provide an indication of vascular compromise. When a triphasic signal changes to a monophasic signal the provider needs to consider loss of flow. This signal is evaluated in conjunction with other physical examination evidence of perfusion (1).

Determining the arterial pressure index (API) is an important adjunct to the physical examination. A Doppler is used to determine the systolic blood pressure distal to the penetrating injury. The systolic pressure is then measured in the same location in the contralateral uninjured extremity. The ratio of the injured to the uninjured extremity is the API. A normal API is greater than or equal to 0.9. A ratio of less than 0.9 is indicative of a vascular injury and necessitates further evaluation (1–3). The sensitivity and specificity of API of less than 0.9 is 87% and 97%, respectively. In one study when insignificant injuries were excluded the sensitivity of API less than 0.9 increased to 95% (4).

Ankle-brachial index (ABI) is often considered synonymous with API. The ABI is calculated as follows: systolic blood pressure at dorsalis pedis or posterior tibialis divided by the brachial systolic blood pressure. An ABI less than 0.9 is considered abnormal. Typically, ABI has been used in the diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease, although it is not uncommonly used for trauma patients as well. In a patient with underlying peripheral vascular disease obtaining both an ABI and an API may be useful in identifying a new injury due to trauma.

The other “P”s of arterial compromise leading to ischemia include pallor, pain, poikilothermia, paresthesias, and paralysis. Additional findings may include tenseness of the extremity, coolness to touch, and delayed capillary refill (>3 seconds). Unfortunately, some of these signs require a patient who can relate these complaints, and many multiply injured patients cannot. In addition, concomitant neurologic injury of the extremity may present with similar findings. Careful examination is necessary to differentiate the paresthesias of vascular insufficiency from those of neurologic injury. As many as 70% of upper- and 30% of lower-extremity vascular injuries have associated nerve damage, of which 40% to 45% result in permanent deficit.

Many vascular injuries appear relatively innocuous at first glance. Penetrating wounds of an extremity can present with a small entrance site that harbors significant underlying vascular damage. Blunt injury may be quite misleading because of minimal obvious external signs. Thus, repeat examination of the patient is important to look for evolving signs of vascular injury.

Finally, the structural integrity of the skeletal system must be evaluated. About 18% of patients with peripheral vascular injuries have an associated fracture from either blunt or penetrating trauma.

ED EVALUATION

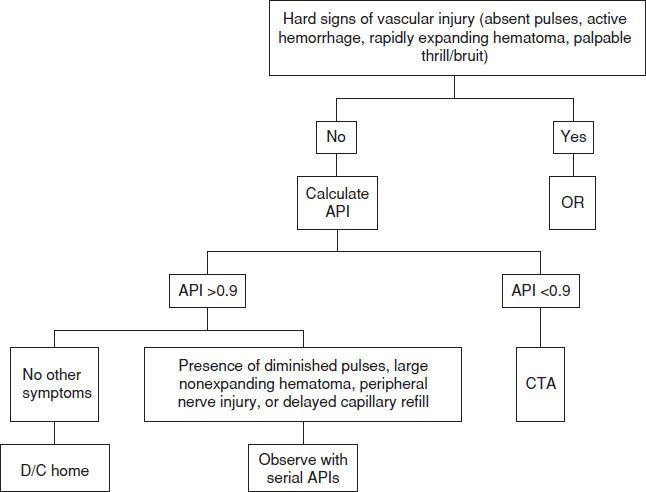

Initial physical examination findings will dictate further evaluation. Patients with hard signs of vascular injury (Fig. 36.1) require immediate intervention. Hard signs include absent pulses, active hemorrhage, rapidly expanding hematoma, and palpable thrill/bruit. In such cases, operative intervention should not be delayed for other diagnostic studies or radiographic imaging, unless the location of the vessel injury cannot be determined clinically (5). In the absence of hard signs in a hemodynamically stable patient, further evaluation can be undertaken. Patients with an API <0.9 require further testing. Those with soft signs of injury (diminished pulses, large nonexpanding hematoma, peripheral nerve injury, or delayed capillary refill) and proximity wounds can be followed with serial physical examinations, tracking the API (3,6–9). Color-flow duplex Doppler ultrasonography can also be used to assess patients with soft signs (10–12). Color-flow duplex Doppler ultrasonography interprets the sound of blood flow and shows it as red and blue colors based on the speed and direction of the flow relative to the ultrasound probe. This sonographic technique will easily demonstrate absence of arterial flow but is less valuable for more subtle injuries such as intimal flaps or pseudoaneurysms that may not interrupt blood flow in the damaged vessel (10).

FIGURE 36.1 Peripheral vascular injury clinical algorithm.