Figure 14.1. Suprascapular nerve block. The spine of the scapula is marked and the midpoint identified by the intersection of the line from the tip of the scapula. The notch lies approximately 1 in. above and lateral to the intersection of these lines.

3. A 4-in. needle is introduced at the “X” and inserted perpendicular to the skin to gently contact the scapula. The needle is then “walked” superior and medially to enter the suprascapular notch. Once the notch is located, the needle is advanced 1 cm.

4. At this point, 10 mL of local anesthetic can be injected with a high probability of success. Although not necessary for block success, paresthesias of the shoulder joint can be sought or the nerve can be stimulated to produce rotation of the humerus.

B. Elbow block. Three separate injections are required. Because the branches of the sensory nerves of the forearm have already ramified extensively and cross this joint superficially in a diffuse subcutaneous network, good sensory anesthesia of the forearm itself is difficult to obtain. Blockade of the major nerves here really produces only anesthesia of the hand and is not significantly different from block at the wrist itself. Therefore, these techniques are not often employed.

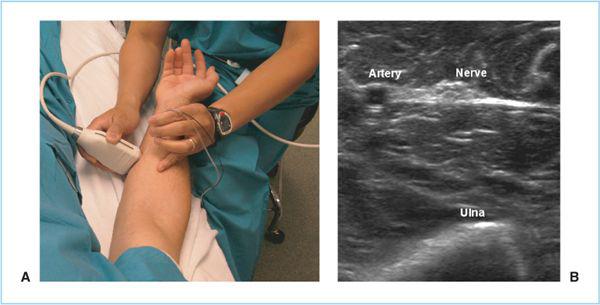

Figure 14.2. Ultrasonographic ulnar nerve block in mid-forearm. A: Surface anatomy. B: Ultrasonographic image.

1. For the ulnar nerve, the patient’s elbow is flexed approximately 30 degrees and the sulcus of the median condyle of the humerus is identified. Excessive flexion may allow the nerve to roll laterally out of the groove. With a 25-gauge needle, 3 to 5 mL of local anesthetic is injected below the fascia into the groove. Paresthesias may be sought or ultrasonography used, but are not needed. Intraneural injection or excessive pressure in this tight space should be avoided to reduce the chance of nerve injury. In an effort to avoid the risks of injecting in the cubital tunnel, ultrasound-guided block at the mid-forearm has been described (Figure 14.2) (4).

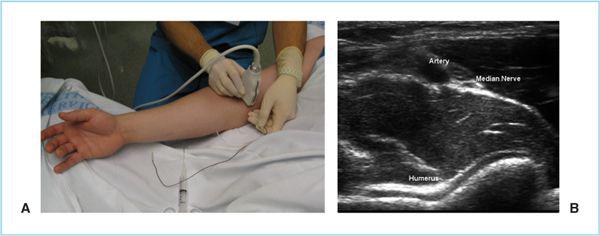

2. For the median nerve, the elbow is extended and a line is drawn across the arm between the two condyles of the humerus, usually two fingerbreadths above the flexion crease. The pulsation of the brachial artery is identified at the medial aspect of this line. A 1.5-in. 25-gauge needle is inserted on the ulnar side of the artery and directed inward toward the humerus. For the most reliable anesthesia paresthesias are sought, but they may be unobtainable if partial anesthesia already exists. If they are not found, a “wall” of 5 to 7 mL of solution is placed alongside and deep to the artery. Ultrasound can be used for more direct imaging (Figure 14.3).

3. For the radial nerve, the tendon of the biceps is identified along the intracondylar line by asking the patient to flex the muscle. With the arm then extended, a needle is inserted lateral to the biceps tendon in the groove between it and the brachioradialis. The needle is advanced slightly cephalad and medial to contact the lateral condyle of the humerus and 5 to 7 mL of solution is injected in a fanwise pattern as the needle is withdrawn. A paresthesia will improve the chance of successful anesthesia because the radial nerve is less easily located than are the median and the ulnar nerves. An additional 3 to 5 mL of solution injected subcutaneously in the groove should provide anesthesia for the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm. Alternatively, ultrasound can be used (5) (Figure 14.4).

Figure 14.3. Ultrasound Block of Median Nerve at the Elbow. The arm is placed in supination and the probe placed 2 cm above the crease over the pulse (A). The nerve is seen just lateral to the pulsatile vessel (B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree