Figure 9.1. Landmarks for intercostal block. The inferior borders of the ribs are identified at their most prominent point on the back. The marks usually lie along a line that angles slightly medially from the 12th to the 6th rib. The marks for the 12th rib usually lie approximately 7 cm from the midline. For a celiac plexus block (see Chapter 11), a triangle is drawn between the 12th rib marks and the inferior border of the 12th spinous process, with the base formed by joining the two rib marks with a straight line. For lumbar somatic (see Chapter 10) or lumbar sympathetic blocks (see Chapter 11), the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae are identified by drawing a line across the superior border of the lumbar spinous processes; the transverse process for each vertebra usually lies along this line in the lumbar area.

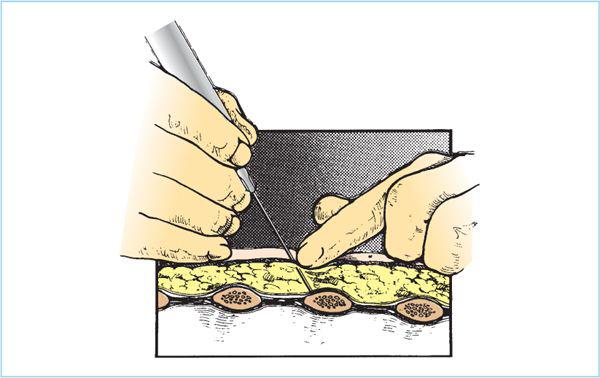

Figure 9.2. Hand and needle position for intercostal block; needle on rib. The index finger of the cephalad hand identifies the lower margin of the rib and the needle is gently inserted onto the bone. The cephalad hand is then used to grasp the hub of the needle and control the movement of the syringe.

6. With the needle resting safely on the rib, the cephalad hand now assumes control of the needle and syringe. The hub of the needle is grasped between the thumb and forefinger while the middle finger rests along the needle shaft (Figure 9.3). The ulnar border of the palm rests on the back and steadies the hand to prevent unintentional changes in depth. The fingers of the caudad hand now move to the rings of the syringe and prepare for injection. While maintaining a 20-degree cephalad angulation of the needle and syringe, the needle tip is raised slightly off the periosteum and “walked” inferiorly until it passes under the inferior border of the rib. The natural traction of the skin (previously pulled upward to move the skin wheal over the rib) helps move the needle to the correct position. The syringe and needle must always remain parallel to their original cephalad angulation with each “step” toward the rib margin. The most frequent cause of inadequate analgesia is allowing the syringe to pivot to a caudad angle.

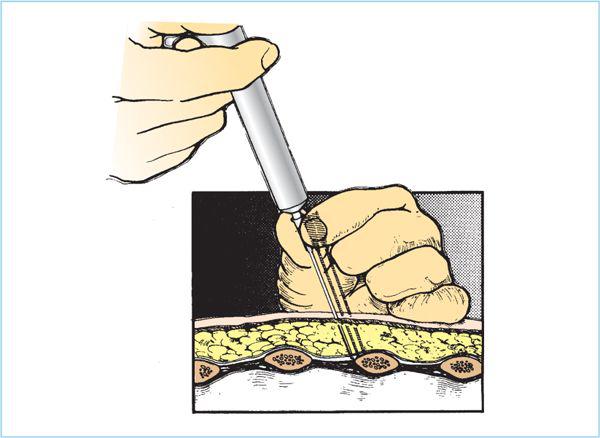

7. Once the needle is under the rib, the cephalad angulation is maintained and the needle is advanced 2 to 3 mm to lie in the intercostal groove. While the cephalad hand continues to control the syringe, 3 to 4 mL of anesthetic solution is injected. Intravascular injection should be prevented by careful aspiration. A deliberate infinitesimal “jiggling” of the needle tip may help prevent intravenous injection. If the needle lies within a vessel, the jiggling makes the intravascular presence temporary. Paresthesias are not necessary unless a neurolytic block is sought. During the injection, the upper hand rests on the chest wall, providing firm control of the syringe. The fingers of the caudad hand are used only to inject, not to advance the syringe or needle.

Figure 9.3. Hand and needle position for intercostal block; needle under rib. The depth of the needle is controlled by the hand resting on the back. The other hand injects solution when the needle is under the rib, but this is the only function performed while the needle is near the pleura.

8. After injection, the needle and syringe are immediately moved back to the safe dorsal surface of the rib. The fingers of the caudad hand are removed from the rings of the syringe, and the barrel is cradled between the thumb and forefinger to allow control of the syringe. Now the upper hand relinquishes control to the caudad hand and is again employed to seek the next rib while the needle remains “parked” on the rib just blocked.

9. By alternating control of the syringe between the hands, the syringe and needle are moved from one rib to the next. If the syringe is to be refilled, it is detached from the needle, and the needle is left in the skin as a marker of the last nerve injected.

10. The ribs of the opposite side may be injected by reaching across the midline or by moving to the opposite side of the stretcher. If the anesthesiologist moves to the opposite side, the syringe is best held in the caudad hand again. This is now an opposite arrangement, and appears awkward to the beginner when the nondominant hand is caudad. If a right-handed anesthesiologist attempts to block the patient’s right side with the syringe in his or her right hand, it is difficult to maintain the necessary cephalad angle. The needle often pivots and points caudad when “walked off” the rib, and the local anesthetic (LA) solution is injected away from rather than toward the nerve.

11. If a celiac plexus or lumbar somatic block is to be added, it is performed at this point.

12. After completion of the block, the stretcher can be taken to the operating room and the patient simply rolled over onto the operating table, where the block can be tested and further anesthesia and surgery can begin.

B. Intercostal nerve block, midaxillary approach. When the patient’s abdomen is distended or pain prevents the prone or lateral approach, the intercostal nerves can be reached in the mid- or posterior axillary line while the patient lies supine. This is also a good approach for postoperative pain relief at the conclusion of surgery if intercostal blocks were not performed at the beginning of the procedure. It is more awkward, but it is not difficult technically.

1. With the patient in the supine position, the patient’s arms are extended laterally on armrests. The ribs are palpated and marked as far posteriorly as practical, usually in the posterior axillary line.

2. Skin preparation and draping are done on both sides, and skin wheals are raised if the patient is alert. (This can be performed at the start or end of a general anesthetic with no need for local anesthesia.)

3. The anesthesiologist may stand either at the head of the bed or at the side. The technique of injection is the same as that in the prone position, with the syringe held in the caudad hand and control alternating between the upper and lower hands as the needle is “walked off” the rib, injection is made, and the syringe is advanced to the next rib.

C. Continuous intercostal block technique. A continuous technique has also been described, using insertion of a standard epidural catheter in the intercostal space by means of a Tuohy needle. This may produce anesthesia of several levels because of medial spread of injected solutions to the peridural or paravertebral levels. This usually provides anesthesia for three or four segments. This technique of intrapleural injection may be useful for postoperative analgesia (see Chapter 10).

D. Rectus sheath block. Bilateral blockade is necessary for midline analgesia.

1. The original approach is a tactile one. A 4-cm (1.5-in.) 22-gauge needle is inserted on each side just medial to the lateral border of the rectus muscle at the level of the umbilicus. The needles are advanced until the anterior sheath of the rectus is identified by an increased resistance, or the firm fascial plane is identified by moving the needle back and forth until a “scratching” sensation is appreciated. The anterior sheath is entered, and then the posterior sheath sought in a similar manner. LA (10–20 mL) is then injected on each side after aspiration and a suitable test to avoid intravascular injection. If the fascial planes cannot be identified easily, the technique should be abandoned to avoid the risk of peritoneal entry and perforation of a viscus.

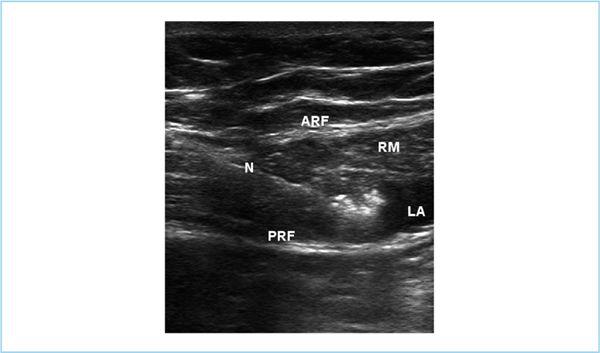

2. This block is easier to perform with ultrasound guidance, which allows easy identification of the fascial planes, and can reduce the chance of intravascular or intraperitoneal injection by direct visualization of the needle tip (Figure 9.4). The planes are identified by placing the probe lateral to the umbilicus, and an in-plane injection made with the same needle as above, depositing the LA just above the posterior sheath.

Figure 9.4. Rectus sheath block. The terminal branches of the intercostal nerves of the abdomen lie between the posterior rectus sheath and the muscle. The needle (N) can be advanced in-plane from the lateral border of the rectus muscle (RM) to pierce the anterior fascia of the rectus sheath (ARF) and stop on the anterior surface of the posterior sheath (PRF). Local anesthetic (LA) injected in this plane will produce anesthesia of several of the terminal branches, usually T9-11. Blockade needs to be performed bilaterally to produce anesthesia for periumbilical procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree