Medications/dose/frequency

Duration

PPI + Clarithromycin 500 mg bid + Amoxicillin 1,000 mg bid

10–14 days

PPI + Clarithromycin 500 mg bid + Metronidazole 500 mg bid

10–14 days

PPI + Amoxicillin 1,000 mg bid then:

5 days

PPI + Clarithromycin 500 mg bid + Tinidazole 500 mg bid

5 days

Salvage regimens

Bismuth subsalicylate 525 mg qid + Metronidazole 250 mg qid +

Tetracycline 500 mg qid + PPI

10–14 days

PPI + Amoxicillin 1,000 mg bid + levofloxacin 500 mg daily

10 days

Clinical Presentation of Peptic Ulcer Disease

The majority of patients who are diagnosed with PUD complain of pain in the epigastric region. The pain is often described as a localized burning, aching, or “gnawing” pain. Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, bloating, anemia, and anorexia or weight loss due to decreased oral intake secondary to symptoms. An extensive and thorough history should be elicited from the patient. In particular, the questioning should focus on previous episodes or symptoms consistent with PUD, correlation with oral intake, and the patient’s association with known ulcerogenic risk factors. An aggressive medication history should also be attained with a specific focus on NSAIDs, aspirin, antisecretory medications, consumption and correlation of antacid use, and a complete social history including alcohol, tobacco, and substance abuse as well as recent psychological stressors.

Duodenal ulcers characteristically have a cyclic type of associated pain. Patients often awake from sleep at night with epigastric pain; however it is usually resolved by the time they awake. Throughout the day, pain recurs 1–2 h after eating a meal and then temporarily dissipates with oral intake or antacids. Symptoms worsen and become more constant if the ulceration erodes posteriorly into the pancreas. Back pain may then also ensue. Pain with palpation during physical exam is an inconsistent and unreliable finding.

Gastric ulcers usually present with epigastric pain that is coupled with oral intake. Patients often complain of pain within 30 min of eating, and at times, symptoms can be aggravated by oral intake. In spite of this, many patients claim to have at least temporary relief of symptoms with oral intake or antacids. Symptoms from gastric ulcers can also be reliably vague and nonspecific in nature leading to a circuitous and extensive differential diagnosis and workup. PUD should be a differential diagnosis for any patient with abdominal symptomatology.

The most common indications for acute surgical intervention for PUD are bleeding and perforation [32]. Anemia may be the presenting symptom with chronic PUD; however, chronic bleeding is rarely managed surgically as most lesions will respond to medical management with compliance. Other reasons for surgical intervention due to PUD include intractable pain, refractory PUD, gastric outlet obstruction, known malignancy, and sequelae secondary to gastrinomas (ZES). Since the majority of emergent procedures for PUD involve perforation or bleeding, the remainder of the chapter addresses surgical management for this population of patients as it pertains to the acute care surgeon.

Bleeding Peptic Ulcer Disease

Sixty percent of all upper GI bleeds are secondary to PUD [34]. Of all deaths that are felt to be attributable to PUD, bleeding is the most common cause of mortality. This patient population is usually older than 65 years of age with concurrent chronic co-morbidities [15]. Although 80% of UGI bleeds are self-limited, there is an overall mortality of 8–10% in those that continue to bleed or have recurrent bleeds. Recurrent bleeds occur in 20–30% of patients and the mortality after a re-bleed ranges from 10 to 40%. Not surprisingly, the onset of a GI bleed during an unrelated hospital stay is associated with a higher mortality rate (33%) than an initial bleed outside of the hospital or before admission (7%) [14, 35]. The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) investigated the correlation of eight different disease co-morbidities with outcomes in patients with upper GI bleeding. These included central nervous system, cardiac, gastrointestinal, hepatic, pulmonary, neoplastic, renal, and psychological stress. The mortality rate for an upper GI bleed with no concurrent diagnoses was 2.5%. However, if the patient had three coexisting diagnoses, the mortality rate rose to 14.6%, and then to 66.7% with six diagnoses [36].

Due to the significant amount of blood supply to the stomach, 35–40% of gastric ulcers will bleed, but significant hemorrhage is more associated with type II and type III gastric ulcers [14]. Gastric ulcers are more commonly found in older patients. This explains the correlation with increased morbidity and mortality in patients with bleeding gastric ulcers in comparison to bleeding duodenal ulcers. The duodenum, however, also has a generous blood supply from the gastroduodenal artery (GDA), which lies just posterior to the duodenum. When a duodenal ulceration progressively erodes through the duodenal wall and into a branch of the GDA, or the artery itself, the resultant bleeding can be substantial. Fortunately, the majority of duodenal ulcers are superficial in nature, and most bleeds are self-limited or amenable to endoscopic interventions [35]. In reality, the majority of duodenal ulcers will present as minor bleeds with guaiac-positive stools or melana. However, approximately 25% of all upper GI bleeds that present for urgent treatment are due to duodenal ulcerations [14].

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to PUD presents as hematemesis, melana, or occasionally hematochezia with massive hemorrhage. Not uncommonly, patients will present after actively bleeding or possibly with syncope to the emergency department with a history of having been “found down” at home for some unknown amount of time. These patients are frequently hemodynamically unstable due to hemorrhagic shock. Aggressive resuscitation and transfusion may be required to stabilize the patient enough to even tolerate endoscopy for diagnostic or therapeutic measures.

As with any critically ill patient that is hemodynamically unstable, the standard airway, breathing, circulation (ABC) algorithm should be followed by verifying a patent or secure airway, ensuring adequate oxygenation and ventilation, and then focusing on the patient’s circulation and hemodynamics. Two large-bore IVs should be attained for volume resuscitation with crystalloid or blood products if significant hemorrhage is suspected or known to have occurred. If peripheral access is not available, a central venous catheter, such as a large-diameter cordis catheter, should be placed to better facilitate resuscitation and transfusion. Blood products should be available and transfused as necessary, and coagulopathies should be addressed and corrected. A Foley catheter is usually placed so that accurate urine output can be monitored to reflect kidney perfusion. Central venous lines and arterial lines are often placed in order to accurately monitor hemodynamic parameters, volume status, and resuscitation efforts.

If the source of bleeding is unclear, an upper GI source versus a lower GI source, a nasogastric tube should be inserted and a gastric lavage should be performed looking for clots or bloody aspirate. Some would advocate irrigation with ice water or cold saline solution until the nasogastric tube irrigation is clear as the iced irrigation will usually stop or slow the bleeding. Although there is no evidence basis behind the practice, most practitioners will immediately start intravenous PPIs or H2 blockers while resuscitating. Once the patient is resuscitated and hemodynamically stable, the upper endoscopy can be facilitated. These patients are critically ill with the potential for instability, regardless of the endoscopy findings. The majority of these patients, and in particular the elderly, frail, or those patients with multiple co-morbidities, should be monitored in an ICU setting with serial hemoglobin monitoring for a minimum of 24–48 h after the initial event.

Endoscopy is first-line treatment for all upper GI bleeds, especially and including variceal bleeds. Many facilities will consult a gastroenterology service; however, many general surgeons also have privileges to perform interventional endoscopic procedures. A surgical endoscopist would also have the advantage of visualizing the anatomy and location of the bleed. This would be optimal should endoscopic measures be unsuccessful and operative intervention become necessary. Either way, the surgical team should be present to visualize the source of bleeding and the interventions attempted for hemorrhage control in order to formulate an operative plan. In the hands of a skilled endoscopist, surgical intervention is only required in 5–10% of bleeding ulcers, and many upper GI bleeds will actually stop spontaneously [31]. There are several different scoring systems that have been developed to predict the need for intervention for control of bleeding. The use of these prognostic scoring systems to identify patients at greater risk is one of the recommendations from the international consensus of recommendations for management of non-variceal upper GI bleeding that was published in 2010 in the Annals of Internal Medicine [37]. Gastroenterologists as well as surgeons should be comfortable and familiar with these scoring systems. Blatchford published a scoring system in Lancet in 2000 that is likely the most referenced. The system uses both clinical and laboratory data to help predict the likelihood of need for intervention to attain hemostasis. Patients with a score of less than or equal to 3 have a 6% chance of requiring intervention for hemostasis, whereas those with a score of 6 or higher have a greater than 50% chance of needing endoscopic or surgical intervention for control of hemorrhage [38] (see Table 17.2 and Fig. 17.1).

Admission risk marker | Score component value |

|---|---|

Blood urea (mg/dl) | |

6.5–8.0 8.0–10.0 10.0–25.0 >25.0 | 2 3 4 6 |

Hemoglobin (g/dl) for men | |

12.0–13.0 10.0–12.0 <10.0 | 1 2 6 |

Hemoglobin (g/dl) for women | |

10.0–12.0 <10.0 Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) 100–109 90–99 <90 | 1 6 1 2 3 |

Other markers | |

Pulse > 100 bpm Presentation with melana Presentation with syncope Hepatic disease Cardiac failure | 1 1 2 2 2 |

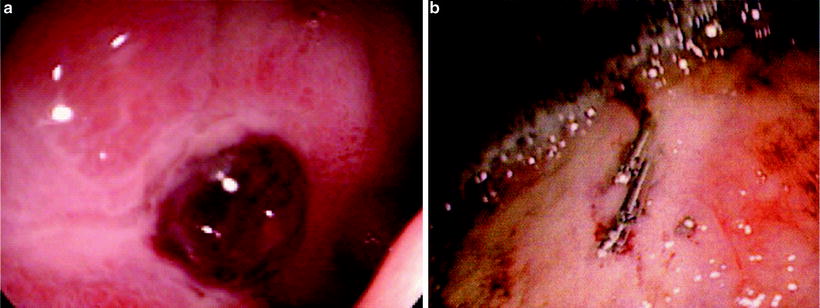

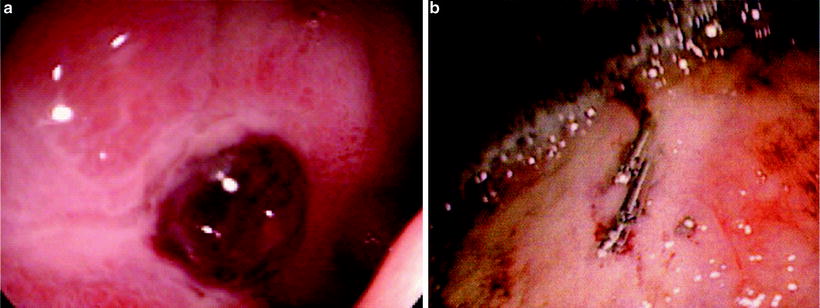

Fig. 17.1

(a) Ulcer in the bulb of the duodenum with overlying clot (b) Endoscopic clips used to control hemorrhage from a gastric ulcer

The first goal of endoscopy is to locate and visualize the source of bleeding, and there are many endoscopic techniques used for control of upper GI hemorrhage. There is often excessive clot over the lesion, and irrigation is necessary to visualize the mucosa below the clots. This is done with caution as not to disturb the clot directly over the lesion and the hemostasis that may have already been achieved. Indications for endoscopic therapeutic intervention include active bleeding or oozing at an identified site, stigmata of a recent bleed such as a large blood clot, or the presence of a visible vessel at the base of the ulceration. If the lesion is no longer bleeding, or if it is merely oozing, epinephrine is often injected in or around the lesion and the surrounding mucosa in order to employ its vasoconstrictive properties for assistance with clot formation. Beyond injection, there are several other methods of direct vessel control depending upon the source and location of the bleed. Cautery may be used to provide hemostasis, or sclerosing agents may be directly injected into the bleeding vessel. Clips can be placed directly on a visualized vessel or circumferentially to address the rich vascularity of the region. Banding is more frequently used on variceal bleeds, but can also be successful depending upon the source. Most endoscopists will use epinephrine in association with another method of intervention such as clips or cautery. Dual intervention has been shown to improve the success of initial endoscopic hemorrhage control and also to decrease the incidence of recurrent bleeding [39, 40].

The majority of upper GI bleeds can be initially controlled via endoscopic interventions; however, 15–20% of patients will experience recurrence of bleeding from the site of ulceration [41]. It is the surgical team’s responsibility to evaluate the patient and his or her co-morbidities, the cause of bleeding, and any other extenuating factors to decide if and when operative intervention is necessary. Historically, many surgeons have used a threshold of six transfused units of packed red blood cells as the deciding point to proceed with operative intervention. The number six certainly defines the need for excessive transfusion, but several other factors need to be considered along with the patient’s transfusion requirements. The location of the ulcer should be influential in the decision of whether or not to intervene early. In particular, lesions in areas with grossly exposed vasculature, those with abundant blood supply such as posterior duodenal ulcers, or ulcers on the lesser gastric curvature with extensive inflow from the left gastric artery may benefit from early operative intervention.

Many endoscopists routinely perform a second-look procedure at 24 h after the initial endoscopic intervention. There is also frequently a trend to repeat therapies such as cautery or injection of epinephrine in order to prophylactically treat continued oozing or to reinforce previous interventions. If the re-bleed is significant, many practitioners will proceed with repeat endoscopic therapeutic interventions. However, if the source was visualized on previous endoscopy, operative intervention may be the more prudent decision. In a prospectively randomized study performed at a high-volume center, Lau and colleagues demonstrated a 75% success rate in control of re-bleeds via repeat endoscopic intervention. They also found similar mortality rates and decreased complication rates when compared to a similar group of patients who underwent surgical intervention. Additionally, their data recognized two factors that independently predicted failure of repeat endoscopic interventions for re-bleeding: hypotension and ulcers greater than 2 cm [42]. Elemunzer et al. did a meta-analysis of ten prospective studies to assess re-bleeding after endoscopic therapy for hemorrhage due to PUD. They found the rate of re-bleeding to be 16.4%. The following factors were found to be independently predictive of re-bleeding after endoscopic interventions: pre-endoscopic hemodynamic instability, comorbid illness, active bleeding at endoscopy, large ulcer size (>2 cm), posterior duodenal ulcerations, and ulcerations on the lesser gastric curvature [43]. Every patient must be individually evaluated and the transfusion requirements, hemodynamic status, and co-morbidities taken into consideration. However, it seems reasonable to proceed with early surgical intervention after the first endoscopy if the ulcer is greater than 2 cm, there is hemodynamic instability, there was extensive hemorrhage, the location of the ulcer is concerning (the posterior duodenum or the lesser gastric curvature), or the patient is greater than 60 years of age and/or has multiple co-morbidities (Fig. 17.2).

Fig. 17.2

Algorithm for contemporary management of upper GI bleed due to peptic ulcer disease

In complicated patients with intricate surgical or medical histories, localizing the source of the hemorrhage and identifying the best method to attain hemostasis may be challenging. A technetium-99 m tagged red blood cell scan is a nuclear study that can identify bleeding at 0.1 ml/min and therefore may be beneficial in identifying a slow GI bleed. The study may be difficult to facilitate as availability may be institution dependent, and although it may be somewhat sensitive, it lacks specificity in localization of hemorrhage [44]. However, this information can be instrumental at times in helping to guide the next stage of clinical intervention. Computed tomography angiograms (CTA) have recently been used more frequently with lower GI bleeding for source localization. Depending upon the patient and the clinical scenario, a CTA may be helpful in localizing bleeding in the upper GI tract as well. Modern-day multi-detector CT scans can detect bleeding at a rate of between 0.35 and 0.40 ml/min, which is improved sensitivity in comparison to angiography. CT scans may be useful for identification of an upper GI bleed; however rarely is there a practical need for the expense or the radiation exposure incurred without any means of truly effecting prognosis or outcomes.

A resource that has become increasingly more utilized in critically ill and complicated patients (those with re-bleeding, uncertain endoscopic findings, or those who are at high risk for general anesthesia) is angiography and interventional arterial embolization. Angiography can identify bleeding at a rate of 0.5 ml/min and is less sensitive than a tagged RBC scan. However, angiography can be used in conjunction with fluoroscopy to localize the region of bleeding and to then embolize the primary blood supply to that region. The most common vessel to be embolized in interventional procedures for bleeding PUD is the GDA followed by the left gastric artery. On average, active bleeding is demonstrated about 50% of the time leaving 50% of the interventions categorized as empiric therapy. Selective embolization is performed primarily using either coils or a gel foam material. Although the stomach and duodenum have a rich vascular supply, there is an associated risk of ischemia with any embolization procedure to not only the stomach and the duodenum but also the pancreas [45–47]. Therefore, interventional radiologic procedures should never be introduced as first-line therapy. All risks and benefits of embolization should be thoroughly evaluated in relation to the patient and the clinical scenario. Post-procedurally, all patients should be monitored closely for any clinical signs of re-bleeding or ischemia with telemetry, serial abdominal exams, and serial laboratory values including base deficits, lactate levels, and complete blood counts to monitor for continued bleeding and leukocytosis.

Regardless of the decision to operate, to repeat endoscopy, to consult interventional radiology, or to observe closely with medical management, the surgical team should remain intimately involved in the care of this population of patients until they are hemodynamically stable and are tolerating oral intake without signs of continued bleeding.

Operative Intervention for Bleeding Peptic Ulcers

Once the decision has been made to operate on a patient with an upper GI bleed, a thorough evaluation of the intraoperative findings and the clinical scenario will help to guide which operation is most appropriate for the patient. With the advancements in endoscopic control of enteric bleeds, the patients that fail endoscopic management tend to be those with the highest risk factors for surgical intervention. Given the shift in the population now requiring these procedures, the historically indicated procedures for stable elective patients may not always be the safest and most appropriate intervention. The type of operation performed should initially be based on the patient’s overall clinical picture and hemodynamic status. In unstable patients, the procedure should provide hemostasis within the least amount of time under general anesthesia. Additional procedures can be done at a later time, if necessary, once the patient has stabilized. Other factors that should be considered are the possibility of malignancy, coinciding perforation or obstruction, and the location of the ulcer.

The generalized surgical principles for the treatment of an acute bleed secondary to PUD are relatively straightforward. The most important goal is obviously hemostasis. The option of an antisecretory procedure with respective drainage as indicated may then be considered. Oversewing of the ulcer is the most common intervention for bleeding duodenal ulcers. Bleeding gastric ulcers, although rare, can also be oversewn, but they must additionally be biopsied to rule out malignancy. Dependent upon the patient’s clinical presentation, the surgeon’s experience, and the patient’s history of PUD, medical compliance, and co-morbidities, a highly selective vagotomy (HSV) or a truncal vagotomy with drainage procedure may additionally be performed. The third category of treatment options includes resection or excision of the ulcer which may also involve a vagotomy and a drainage procedure dependent upon the location and indication.

Traditionally the decision of whether or not to do an antisecretory procedure was dependent upon the location of the ulcer. Type II and type III ulcers have classically been categorized as lesions that evolve secondary to acid hypersecretion. The historical recommendation has always been to perform a truncal vagotomy with a gastric emptying procedure. If the pylorus is not resected or bypassed, a pyloroplasty would be the necessary alternative. Some would advocate the use of a HSV to allow gastric emptying and avert the need for pyloroplasty or antrectomy. However, given the relative rarity of HSV in modern-day general surgery, the majority of younger surgeons do not have the exposure or experience to perform the procedure with dependably successful outcomes. In considering our advances regarding H. pylori treatment, the pathogenesis of ulcer formation, and the use of PPIs for acid suppression, the necessity for antisecretory procedures is ambiguous. Truncal vagotomies are associated with some level of dumping syndrome, whether it is clinically significant or not. HSV may be associated with lesser detrimental effects; however, the procedure is less common and certainly more time consuming. The patient’s overall state of health, his or her hemodynamic status, and the location of the bleed must all be taken into consideration when the operative plan is established.

Most modern-day damage control surgery for acutely bleeding PUD involves either resection or oversewing of the ulceration. Patients are then treated postoperatively for assumed H. pylori with an appropriate regimen including PPIs or H2 blockers. In the era of the damage control laparotomy, resection alone also can be performed, leaving the patient in discontinuity with a properly placed nasogastric tube for decompression. A second-look laparotomy can then be utilized, after the patient is adequately resuscitated, for reconstruction or performance of definitive antisecretory and drainage procedures if they are indicated. Regardless of the choice of intervention, it should be understood that the majority of patients requiring surgical intervention for bleeding PUD in the current era have very little physiologic reserve. Operative interventions should focus on expediently addressing the source of the bleeding in order to return the patient back to the ICU for resuscitation and hemodynamic support.

Operative Approach for the Bleeding Gastric Ulcer

Gastric Resection

The procedure of choice for bleeding types I, II, and III ulcers (Fig. 17.3) is a distal gastric resection inclusive of the bleeding ulcer. A Billroth I or Billroth II reconstruction can then be performed depending upon the mobility of the duodenum. As always, the patient’s hemodynamic status is the deciding factor as to whether or not it is appropriate to proceed forward with a definitive anastomotic procedure. If the patient is hypotensive, it would be prudent to do a wedge resection, an oversew procedure, or a damage control partial gastrectomy with nasogastric decompression and an eventual second laparotomy to establish continuity. A wedge resection can easily be performed if the ulcer is on the greater curvature, the antrum, or within the body of the stomach. However, resection may be difficult or inappropriate for type IV ulcerations, lesions on the lesser curvature, or those more proximal to the gastroesophageal junction. Multiple bleeding erosions may require total gastrectomy with eventual creation of a Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy or esophagogastrojejunostomy, depending upon the extent of gastric resection that is required to gain hemostasis.

Fig. 17.3

Active arterial bleeding from a gastric ulcer on the lesser curvature of the stomach

Gastric resections, as well as ulcer excisions, are usually performed with a gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler after the stomach is sufficiently mobilized and cleared of surrounding attachments. A Kocher maneuver is performed in order to mobilize the duodenum for the gastroduodenal anastamosis of a Billroth I procedure. The anastomosis is created by removing, or avoiding initial placement of, the staple line on the inferior portion of the gastrectomy. The anastomosis can then either be handsewn in a two-layer fashion using absorbable sutures or stapled with a GIA stapler placed through a gastrotomy.

If the duodenum is scarred or will not reach the distal stomach remnant, a Billroth II will need to be performed. There are several complications associated with this procedure including duodenal stump leaks and afferent or efferent limb syndromes. The Billroth I primary anastomosis has less incidence of complications, but if there is any tension on the anastomosis, a Billroth II is the procedure of choice. The proximal duodenum should be transected using either a TA stapler or a GIA stapler. Attention should be given to the anatomy in regard to the common bile duct, as it lies just posterior to this region. Additionally, the thickness and induration of the duodenal stump should be evaluated. It may be necessary to handsew the stump closed to avoid a stump leak. Many experienced surgeons would suggest placing an omental patch over the stump as well. In the case of a friable or extremely indurated stump, a lateral duodenostomy tube can be placed in a Stamm fashion to the lateral abdominal wall in order to decompress the duodenum, although this is recommended only in extreme conditions. There are several ways to perform the anastomosis for a Billroth II gastrojejunostomy. The jejunal afferent limb should reach the gastric remnant without any tension, but with no more than 20 cm of length from the ligament of Treitz. Placing the jejunum through a retrocolic window will decrease tension on the mesentery, but antecolic placement is functionally equivalent. There are several methods of constructing the gastrojejunostomy using staplers, 2′0 absorbable sutures, or a combination of both. If the anastomosis is handsewn, it should be a two-layered anastomosis with an outer layer of Lembert sutures and an inner layer of full-thickness absorbable sutures.

The Oversew Technique

Oversewing of a bleeding gastric ulcer is not the ideal procedure, but it may be the most appropriate procedure for a high-risk patient. Remember that all gastric ulcers must be biopsied if resection is not possible, and therefore, if the ulcer is oversewn, a biopsy must be procured. If the location of the ulcer is known, a gastrotomy is made to localize the lesion. The ulcer is then biopsied and oversewn with absorbable sutures to attain hemostasis. The gastrotomy should be closed in a two-layer fashion or via a TA stapler. In type IV ulcers, those lesions located near the gastroesophageal junction, oversewing the ulcer is the procedure of choice as this region is not readily amenable to wedge resection. The area also has a vast blood supply secondary to inflow from the left gastric artery. The appropriate procedure for a type IV lesion then includes oversewing the bleeding ulcer, ligation of the left gastric artery to prevent re-bleeding, and a vagotomy and drainage procedure (pyloroplasty) if the patient is hemodynamically stable.

Truncal Vagotomy and Pyloroplasty

In a stable patient, with straightforward anatomy, a truncal vagotomy should be considered for acid suppression as long as the procedure does not extensively prolong time spent in the operating room. In order to perform a vagotomy, the left lateral section of the liver as well as the triangular ligament must be mobilized. The esophagogastric junction must be retracted inferiorly using gentle tension in order to localize the proximal nerves. Once the nerves are localized, they are isolated using Penrose drains. Clips are placed proximally and distally on each nerve, and a 2 cm long portion of each proximal nerve is excised and sent off to pathology for verification. Exposure and extensive mobilization are often required for this procedure, and therefore should only be pursued in hemodynamically stable patients. If a truncal vagotomy is performed, the vagal intervention to the pylorus and distal stomach is disrupted. If a bypass procedure is not performed, pyloroplasty is necessary to allow for drainage of the gastric contents. The most commonly performed method of pyloroplasty is the Heineke–Mikulicz pyloroplasty. The pylorus is localized and bovie cautery is then used to create a longitudinal full-thickness pyloromyotomy extending from 1 cm proximal to 1–2 cm distal to the pylorus. Traction sutures are then placed superiorly and inferiorly and tension is applied superiorly and inferiorly to convert the longitudinal incision into a transverse incision. The defect is then closed transversely in a double-layer fashion with full-thickness bites using nonabsorbable suture. A Kocher maneuver and adequate duodenal mobilization may be necessary in order to close the incision without tension.

Operative Approach for Bleeding Duodenal Ulcer

As with the management of bleeding ulcers, the same principles of management apply in regard to an acutely bleeding duodenal ulcer. The ulcer can either be oversewn or resected in order to achieve hemostasis. The option to perform a vagotomy and drainage procedure then also needs to be contemplated. The most commonly used approach is by creation of the pyloromyotomy as previously described. The longitudinal duodenotomy incision is extended another 1 cm as needed in order to visualize the duodenal ulcer. As nearly all duodenal ulcerations are located on the posterior portion of the first part of the duodenum, this incision should give ample exposure. A Kocher maneuver can be performed if necessary for exposure and so that the left hand can be used to manually control bleeding. The source of bleeding is usually the gastroduodenal artery. Figure of eight sutures with a heavy suture material, such as 3′0 silk, should be placed superiorly and inferiorly at the base of the posterior duodenal ulcer for ligation of the vessel. Several sutures may need to be placed before hemostasis is attained. A U-stitch should also be placed at the base of the ulcer in order to control any possible hemorrhage from the transverse pancreatic arterial branches that enter the gastroduodenal artery from the posterior aspect. Once the bleeding has ceased, the ulcer should be manipulated in order to verify the stability of the arterial ligation. If true hemostasis has been achieved, the longitudinal incision can then be closed transversely in two layers as a Heineke–Mikulicz pyloroplasty. A Finney pyloroplasty can also be utilized if transverse reapproximation is not attainable. If the patient is stable, a truncal vagotomy would be the classic next step in management. However, the majority of surgeons, as evident by surveys performed in both the United Kingdom and the United States, no longer perform vagotomies on these patients [7, 48]. Although there is no level 1 evidence to support the change in practice patterns, the transition has come about since the availability of medical acid suppression with PPIs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree