Penetrating Neck Trauma

Julie Mayglothling

Penetrating wounds of the neck present a therapeutic and diagnostic challenge to the emergency physician. Mortality among patients who suffer penetrating neck injuries in the civilian population approaches 6%. Fatality rates for major vascular injuries may reach 50% (1). Successful management of a penetrating neck wound demands an understanding of the regional anatomy and those structures vulnerable to injury, familiarity with the options for proper airway management, and appreciation of the evolving concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of significant injuries. Even the most benign-appearing wound may belie serious pathology, and extreme vigilance is essential to avert catastrophic airway, vascular, neurologic, and gastrointestinal complications.

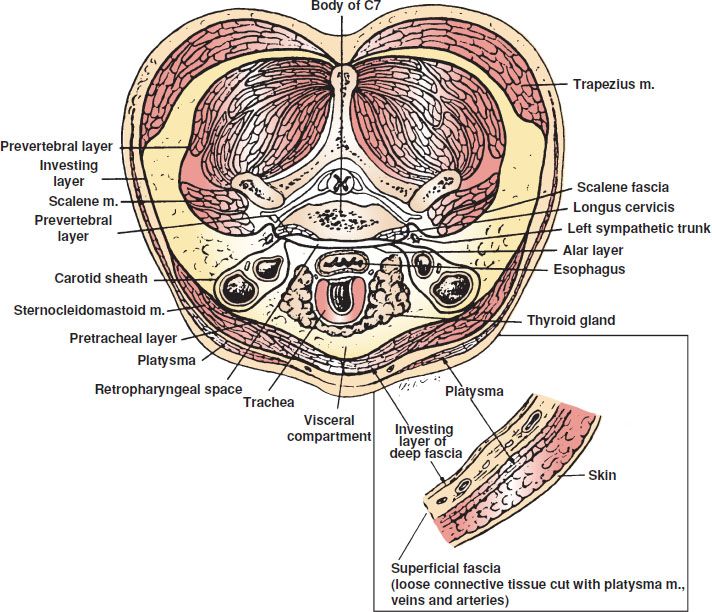

A number of anatomic factors predispose structures within the neck to serious injury in the setting of penetrating trauma. Vital components of the respiratory, vascular, neurologic, and gastrointestinal systems course through the neck. Dense musculature and the structural integrity of the cervical spine afford some protection to these structures posteriorly, but the lack of similar shielding anteriorly exposes them to significant injury. Moreover, the majority of the vital structures of the neck are contained within dense, tightly confined fascial compartments, rendering them vulnerable to distortion and compression when bleeding occurs within the deep tissues (Fig. 27.1). For these reasons, penetrating wounds to the neck are best approached conceptually with regard to the site of external penetration, the depth of the wound, and the potential pathway of injury within the deeper compartments.

FIGURE 27.1 Cross-sectional anatomy of the neck. (From Gray SW, Skandalakis JE, McClusky DA. Atlas of Surgical Anatomy. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1985, with permission.)

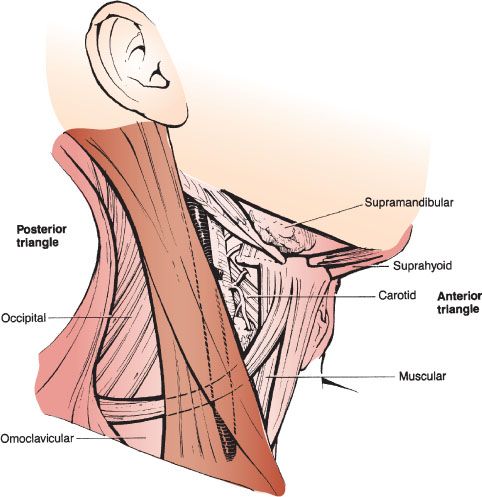

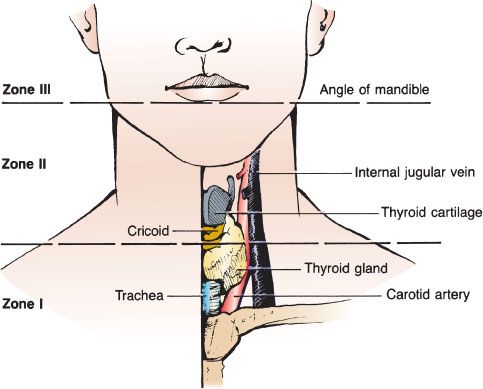

Most sources concur in dividing the external neck anatomically into posterior and anterior triangles. The posterior triangle connotes an area bordered by the posterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly, the anterior edge of the trapezius muscle posteriorly, and the clavicle inferiorly (Fig. 27.2). The defining sides of the anterior triangle consist of the mandible superiorly, the anatomic midline anteriorly, and the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid posteriorly. The anterior triangle is further subdivided into three zones, with penetrating injury to each zone and its underlying structures carrying distinct and important implications for diagnostic evaluation and clinical management (Fig. 27.3).

FIGURE 27.2 Anatomy of the neck: anterior and posterior triangles.

FIGURE 27.3 Anatomy of the neck: zones I, II, and III.

Zone I defines the region between the clavicles and the inferior rim of the cricoid cartilage. Vital structures susceptible to injury after penetrating trauma to zone I include the proximal common carotid, vertebral, and subclavian arteries, the thoracic outlet, the apex of the lung, the trachea, the esophagus, the thoracic duct, and the thyroid. Mortality rates for penetrating wounds to zone I are the highest of the three zones because of the inherent inability to achieve rapid proximal control of vascular injuries and the overall difficulty in gaining exposure to injuries within the thoracic cavity (2).

Zone II spans the distance from the superior edge of the cricoid to the angle of the mandible. Injuries to zone II threaten the carotid and vertebral arteries, the jugular veins, the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves, the cervical spinal cord, the trachea and larynx, and the esophagus. As the most exposed anatomic region of the neck, zone II injuries are the most common penetrating wounds in most series (3).

Zone III extends superiorly from the angle of the mandible to the base of the skull. Vulnerable structures in this region include the distal carotid and vertebral arteries, the salivary and parotid glands, the pharynx, the spinal cord, and cranial nerves IX to XII. As with zone I, management of zone III wounds may be problematic because of the difficulty in gaining surgical access to injured structures and control of bleeding vessels.

Within the anterior neck, the superficial fascia lies immediately beneath the skin and envelopes the platysma, a thin sheet of muscle that extends upward from the upper thorax over the clavicles to cover the entirety of the anterior triangle as well as the anteroinferior portion of the posterior triangle. As it extends cephalad, the platysma crosses the mandible to merge with the musculature of the face. This superficial structure has historically been an important landmark in gauging the potential severity of a wound—violation of the platysma by a penetrating mechanism signifies injury to vital underlying structures until proven otherwise.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Penetrating neck trauma is most commonly the result of a violent attack. This is reflected in the fact that the majority of victims are young adult males, and that most victims have ingested alcohol or other abusive substances immediately prior to the trauma (4). Other mechanisms of injury include unintentional impalements and bites from animals such as dogs. In most societies, stabbings outnumber gunshot and other wounds as the most common cause of penetrating neck trauma. In the United States, however, gunshot wounds account for an increasing proportion of injuries, particularly among the pediatric and young adult population (3).

Low-energy penetrations occur through such injuries as stabbings with knives or other cutting instruments, impalements, or wounds inflicted by air guns, low-caliber handguns, or shotguns at long range. High-energy mechanisms include discharges from rifles and shotguns at close range as well as shrapnel from explosive devices.

Stab wounds to the neck are typically unilateral and more frequently involve the left side because of the higher likelihood of right hand dominance in a facing attacker. As the most exposed portion of the anterior neck, zone II is the area injured most frequently, accounting for 50% to 80% of stab wounds to the neck (1). Information relating to an assault, such as the size of the instrument and the angle of the attack, may yield some insight into the potential depth and tract of a wound. Nevertheless, the external appearance of a stab injury to the neck correlates poorly with its underlying severity, and even the most superficial-appearing injury should be approached as potentially life threatening.

Because of the higher kinetic energy imparted to the tissues by an offending missile, approximately 50% of gunshot wounds to the neck results in injury to vital structures (1). As with stab wounds, the depth and pathway of injury of a gunshot wound to the neck can be difficult to predict based upon its external appearance, particularly when it is secondary to a low-velocity projectile. When the wound traverses the anatomic midline of the neck, however, the likelihood of significant injury doubles (5).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

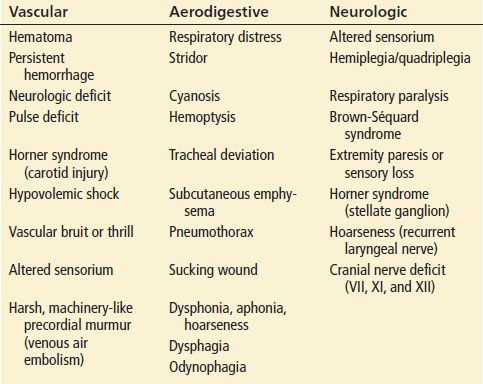

Penetrating trauma to the neck demands consideration of potential injury to vital respiratory, vascular, neurologic, and gastrointestinal structures (Table 27.1). This differential diagnosis should guide the clinician through an initial evaluation that is rapid yet thorough. Moreover, subtle signs of significant injury may not be appreciable initially and can evolve rapidly. Frequent reevaluation of the patient for developing clinical signs and symptoms is therefore essential to avoiding a disastrous outcome.

TABLE 27.1

Signs and Symptoms of Specific System Injuries

Respiratory Injuries

Structures of the respiratory tract that are vulnerable to penetrating neck wounds include the oropharynx, larynx, trachea, and lung apices. Assessment for airway and respiratory compromise takes the highest priority during the initial and subsequent evaluations, and obvious signs of injury include dyspnea, cyanosis, and stridor. Air bubbling at the wound site, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, hemoptysis, voice change, tenderness over the larynx, and unilaterally diminished breath sounds are other important indications of respiratory injury.

Vascular Injuries

Vascular injuries are present in approximately one-fourth of patients and are the leading cause of mortality in the setting of penetrating neck trauma (1). Death results most often from exsanguination secondary to arterial injury, venous injury, or both. Unequivocal or “hard” signs of a major vascular insult include the following:

• Shock either with or without active hemorrhage

• An expanding or pulsatile hematoma

• Carotid bruit or thrill

• Absent radial or ulnar pulses

• Any focal neurologic deficit consistent with hemispheric stroke

Other indications of vascular injury may include diminished pulses in the temporal or facial arteries, decreased breath sounds as a consequence of hemothorax, bleeding within the oropharynx, and signs of venous air embolism such as hemodynamic collapse unresponsive to standard resuscitative measures or the presence of a loud, machinery-like murmur over the precordium.

Gastrointestinal Injuries

Violation of the pharynx and esophagus is frequently unrecognized during the initial evaluation of the patient with a penetrating neck injury, yet the consequences of such an injury can be devastating. Extravasation of saliva, gastric acid, digestive enzymes, and bacteria through a penetrating wound can ignite an aggressive necrotizing inflammatory reaction within the neck and mediastinum. Mortality and morbidity increase sharply when there is a delay in diagnosis and treatment in this setting (6). Pertinent signs and symptoms include dysphagia, odynophagia, hematemesis, and air within the soft tissues as manifested by subcutaneous emphysema or radiographic free air within the retropharyngeal space or mediastinum.

Nervous System Injuries

A number of neurologic injuries can manifest as distinct clinical syndromes after penetrating neck trauma. Gunshot wounds and, occasionally, stabbings that enter the spinal canal from a posterior orientation can partially or completely transect the spinal cord. Complete transection of the cord above the level of C5 may cause acute respiratory failure because of paralysis of the diaphragm. Transection at a lower point will cause paraplegia and loss of upper extremity function according to the level of injury. Hemisection of the spinal cord, or the Brown-Séquard syndrome, yields ipsilateral hemiplegia, loss of tactile and proprioceptive sensation, contralateral loss of pain, and temperature sensation. Injury to the cervical sympathetic ganglia can present with the ipsilateral ptosis and myosis of Horner syndrome. Damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve as it courses in the groove between the trachea and the esophagus impairs vocal cord movement, resulting in dysphonia or hoarseness. Cranial nerve transection may result in ipsilateral drooping of the corner of the mouth (CN VII), inability to shrug the shoulders (CN XI), or tongue deviation (CN XII). Injury to a nerve root as it travels from the vertebral foramen to the brachial plexus causes sensory and motor deficits in the corresponding upper extremity.

Cervical Spine Considerations

There is controversy as to whether cervical spine immobilization should be routinely performed in victims of gunshot wounds to the neck. Although such injury is unlikely to result from a stab wound, high-energy projectiles such as bullets can cause injuries that destabilize the cervical spine. The reported incidence of cervical spine injury as a result of gunshot wound ranges from 2.7% to 22% (7). Victims of gunshot wounds to the cervical spine may suffer neurologic deficit either from direct injury to the spinal cord by a transecting bullet or as a consequence of the concussive force imparted to the cord by a projectile passing in close proximity. Victims of gunshot wounds to the neck who do not manifest a neurologic deficit, on the other hand, are very unlikely to have an unstable cervical spine.

A retrospective review of over 45,000 patients using the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) found that 0.08% of patients with penetrating trauma would have potential benefit from cervical spine immobilization (7). However, the small potential benefit of routine cervical spine immobilization for penetrating wounds to the neck must be weighed against its dangers. Stabilization devices deprive the clinician of direct visualization and easy palpation of the neck, thus increasing the likelihood that signs of life-threatening complications of injury might be missed. Moreover, cervical spine immobilization may make visualization of the vocal cords more difficult, further complicating an already challenging intubation. The NTDB review found that prehospital spine immobilization is associated with higher mortality in penetrating trauma and recommends against its use. For these reasons, the Prehospital Trauma Life Support (PHTLS) course and textbook, recommend that spine immobilization is not indicated in patients with penetrating trauma to the head, neck, or torso without neurologic deficit or complaint (8). Thus, the most recent recommendations promote selective spine immobilization in penetrating trauma only for patients with altered mental status, cervical spine tenderness or an abnormal sensory or motor examination.

ED EVALUATION

Attention to airway patency and protection is the central focus of the initial evaluation of any patient with penetrating neck trauma. Vigilance for signs of actual or impending airway compromise begins with the initial patient contact in the prehospital setting and must continue throughout the victim’s ED evaluation.

Although several acceptable options for establishing definitive airway control in this clinical setting exist, each possesses inherent challenges and the risk of failure or complication. The emergency physician must therefore be familiar with and capable of quickly implementing an array of airway management techniques when confronted with the victim of a penetrating neck wound. At the same time, rapid and thorough assessment of the patient’s circulatory status, the need for emergent operative intervention, and the potential for injury to the major structures of the neck is essential.

In the prehospital setting, all patients with penetrating neck trauma should be considered to have a life-threatening injury. If circumstances allow, prehospital personnel can gather pertinent information such as the circumstances related to the trauma, the character and size of the weapon responsible for the injury, the position of the attacker relative to the patient, and an estimation of the amount of blood lost at the scene.

Immediate airway management in the field is indicated for any patient with acute respiratory distress, stridor, or cardiopulmonary arrest. If transport to an appropriate trauma center will be rapid, attempts at intubation may otherwise be deferred until arrival in the emergency department (ED). High-flow oxygen should be provided, but ventilation via bag valve mask should be avoided if possible because of its potential to force air through a tracheolaryngeal wound and into the surrounding tissues, distorting neck anatomy and further compromising the airway. Direct pressure should be applied to sites of hemorrhage, and at least one large-bore IV catheter should be placed at a site contralateral to any potential vascular injury.

Upon arrival to the ED, the primary survey must be quickly and thoroughly repeated. Indications for emergent airway stabilization include acute respiratory distress or persistent stridor, copious blood or secretions threatening the airway, extensive subcutaneous emphysema, visible expanding hematoma or tracheal shift, and altered mental status. When such frank signs of airway compromise are absent, however, the emergency physician must remain vigilant for subtle indications of airway compromise such as voice change or odynophagia. Early airway management is warranted, as deterioration can be rapid and catastrophic.

Due to potential damage to surrounding structures causing edema and distortion of airway anatomy, airway management in the patient with a penetrating neck injury should be managed as a difficult airway. Many institutions have difficult airway algorithms or carts which should be available for these situations. A number of options exist for appropriate airway management after penetrating neck trauma. Intubation over a fiberoptic bronchoscope in the awake patient may allow for effective visualization of the vocal cords and passage of an endotracheal tube despite the presence of airway distortion or excessive blood and secretions. It may also identify specific laryngotracheal injuries. Its disadvantages include the need for specialized equipment and expertise and the potential to induce gagging and coughing.

In most EDs, rapid sequence intubation (RSI) using a neuromuscular paralytic agent is the primary modality of airway management in trauma (9). Some authors recommend using caution with RSI in this setting, however, arguing that a decrease in muscle tone following paralysis holds the potential to worsen airway distortion and thus invite airway disaster. Appropriate caution and, more importantly, preparation for an alternative means of airway management in the event of failure are therefore essential before attempting RSI after penetrating neck trauma. The increased use of videolaryngoscopy may be particularly useful in situations where visualization of the glottis is difficult, as it has been shown to improve first pass success rates and decreased complications compared to direct laryngoscopy (10). To date, there are no studies specifically evaluating the use of videolaryngoscopy in patients with penetrating neck trauma. Similar to fiberoptic bronchoscopy, significant bleeding or copious secretions may limit visualization using such adjuncts.

The establishment of a surgical airway is the most commonly used rescue technique for airway management after failed RSI among patients with penetrating neck injuries (11). Cricothyroidotomy should be performed with a vertical incision to allow for extension of the incision if the cricothyroid membrane is not easily identified initially. Significant hematoma overlying the cricothyroid membrane is a contraindication to cricothyroidotomy because of the potential to convert a partial cricotracheal separation into a complete disruption. Emergent tracheostomy is warranted in this setting.

When the patient is stable, the wound itself should be inspected but never probed to determine if it has violated the platysma. Wounds that do not penetrate the platysma may be irrigated and closed. Otherwise, a thorough secondary assessment for the signs and symptoms of significant vascular, respiratory, neurologic, and gastrointestinal injury described previously should proceed to determine further appropriate evaluation and management in the ED.

All patients with penetrating trauma to the neck should receive an upright or supine (if cervical spine precautions are being maintained) chest radiograph. Potentially life-threatening injuries such as pneumothorax or hemothorax can be rapidly diagnosed with chest radiograph. In addition, subcutaneous air that may not be appreciated on physical examination may be visualized on plain radiograph and may signify injury to the aerodigestive system. Although it may be difficult to distinguish air from an esophageal or tracheobronchial injury from air tracking through a penetrating wound, any positive finding should prompt strong consideration of and further evaluation for these injuries.

The evaluation and management of all penetrating injuries to the neck has changed with the increasing availability of computed tomography (CT), particularly multidetector CT angiography (CTA). The technology is available in most centers around the clock, and it provides rapid information about the vascular, aerodigestive, soft tissue, and bony cervical spine with high resolution (12). In addition, CT, even one performed without contrast, can provide information regarding the trajectory of the penetrating missile and potential injuries from its path (13). Wounds concerning for vascular injuries that were previously evaluated with arteriography, are now evaluated with CTA with equal sensitivity (1,11). All patients who do not have indications for emergent surgical management, and in whom further testing is warranted, should undergo CTA as a first diagnostic modality.

Duplex ultrasonography, or color flow Doppler imaging, is a modality used for diagnosis of arterial injuries and has been demonstrated to have sensitivities of 85% to 92% and specificity of 100% (14). Specifically in zone I and zone III injuries, duplex ultrasonography may be limited due to bony artifact. However, in situations where CTA may be equivocal due to metallic fragments causing difficulty in visualization of the vessels, ultrasonography may be helpful.

Arteriography used to be the gold standard and used frequently for evaluation of vascular injuries in penetrating trauma. However, given the use and sensitivity of CTA, arteriography has been used mostly as a confirmatory test in equivocal CTA’s or as a therapeutic modality for those patients necessitating embolization or thrombolytic therapy for vascular injuries (1,15).

Evaluation of the digestive system is imperative in patients with a missile trajectory that is adjacent to the oropharynx or esophagus. Most frequently, patients are found to have an injury on CTA that either crosses the mediastinum or comes dangerously close to the digestive structures, and requires further testing with either contrast esophagography (usually with either barium or a high osmolality contrast agent such as Gastrografin or Hypaque) or esophagoscopy (endoscopy). Both modalities have been found to have adequate sensitivity and specificity to be used alone and both do not need to be performed (1,16,17).

Diagnostic laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy are used to evaluate injuries of the larynx and trachea. Most airway system injuries can be initially diagnosed by either physical examination or CT, and endoscopic studies are performed for further evaluation or management of these injuries. CT scans without concern for airway injuries do not need routine evaluation with laryngoscopy or bronchoscopy.

KEY TESTING

• Chest radiography

• Multidetector CTA

• First diagnostic modality for patients who do not have indications for emergent surgical management

• Duplex ultrasonography, or color flow Doppler imaging

• Either contrast esophagography (usually with either barium or a high osmolality contrast agent such as Gastrografin or Hypaque) or esophagoscopy (endoscopy) for evaluation of the digestive system

• Diagnostic laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy are used to evaluate injuries of the larynx and trachea