81 Pelvic Fractures

• Approximately 70% of patients with a traumatically disrupted pelvic ring will have a major associated injury.

• If a patient has displacement of 0.5 cm at any fracture site in the pelvis or has an “open book” pelvic fracture, massive transfusion may be needed.

• Blood loss from open book pelvic fractures and vertical shear injuries can be life-threatening.

• Emergency binding of the pelvis can help reduce pelvic volume and tamponade the bleeding. Binding the fractured pelvis too tightly should be avoided.

Epidemiology

Fractures of the bony pelvis account for 3% of all fractures; however, the overall mortality from pelvic ring injuries is 10% to 15%. Motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) involving cars or cars and pedestrians cause approximately 60% of pelvic fractures.1 Side-impact car collisions more commonly cause pelvic fractures than do head-on car collisions.2 Falls and motorcycle accidents are also significant causes of pelvic ring injuries.

Pathophysiology

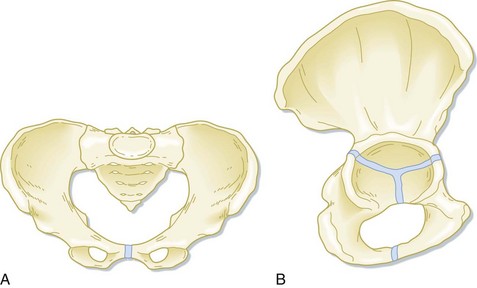

The pelvis provides support for upright mobility by connecting the spine to the lower extremities. When viewed as a whole, the pelvis contains a major ring and two inferior rings. The triangular sacrum and two innominate bones form the major pelvic ring (Fig. 81.1). The sacrum is a fusion of the five sacral vertebrae and distributes the weight of the upper part of the body to the innominate bones. The sacrum also conducts the sacral nerve roots to the pelvic organs. Each innominate bone is a fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubic bones. the intersection of the fusion forms the acetabulum, which articulates with the femur. Posteriorly, the innominate bones are anchored to the sacrum by the anterior and posterior iliac ligaments, two of the body’s strongest ligaments. The sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments attach the sacrum to the ischial tuberosity and the ischial spines bilaterally, thus further reinforcing the posterior arch of the pelvic ring.

Several classification schemes involving the direction of force applied to the pelvis, the bones injured, the degree of instability of the ring, and any associated injuries are used for pelvic ring disruptions. Fracture stability and increases in pelvic volume determine the magnitude of blood loss and potential mortality. See Box 81.1.

Tile Classification of Pelvic Fractures

The Tile classification adopted by the Orthopedic Trauma Association3 describes pelvic fractures by the degree of stability. The type and degree of stability predict outcome and associated injuries (see Box 81.1). Type A fractures are stable and include avulsion fractures and isolated fractures of an inferior pubic ramus, iliac wing, or distal sacrum. These fractures cause local pain but do involve the major pelvic ring.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree