C. Drugs. In children, most local anesthetics should be dosed in milliliter per kilogram to avoid toxicity associated with larger volumes used in adult blocks.

1. Bupivacaine. A dose of 0.25% provides minimal motor blockade with adequate sensory blockade. An easy approximation of caudal dose is 1 mL/kg of 0.25% bupivacaine. The total dose of bupivacaine should not exceed 3 mg/kg. In the epidural space, it lasts 4 to 6 hours. Fifty percent of children will have analgesia for up to 12 hours if adequate doses are employed.

2. Ropivacaine 0.2%, in doses that do not exceed 2 mg/kg, has also been employed (14).

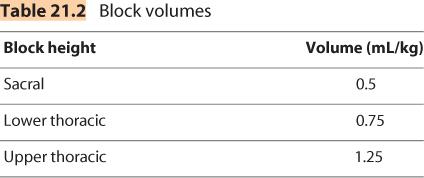

3. An easy calculation of volume is that employed by Armitage (15). A dose of 0.5 mL/kg for sacral blockade, 0.75 mL/kg for lower thoracic segments, and 1.25 mL/kg for upper thoracic levels of blockade (Table 21.2).

4. The rate of uptake of local anesthetic is usually more rapid in children than adults. Using a vasoconstrictor can reduce the rate of uptake and prolong the duration of the block.

5. Neonates may have a higher free drug level and be more susceptible to the toxic effects of local anesthetics. The bolus dose and infusion should be reduced by 30% for infants younger than 6 months to decrease the risk of toxicity. This would result in an hourly maximal rate of 0.25 mg/kg of bupivacaine (16)

D. Technique. The block is usually performed following the induction of general anesthesia and IV placement.

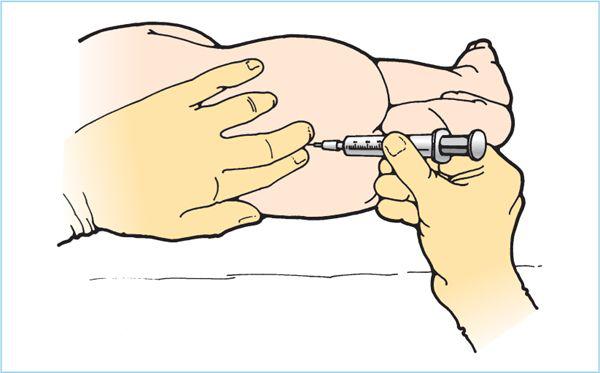

1. The patient is turned into the lateral position, and the hips and knees are flexed similar to the position that would be appropriate for performance of a lumbar puncture (Figure 21.1).

2. The cornua of the sacral hiatus are the most easily palpated as two bony ridges at the beginning crease of the buttocks. It can be useful to identify the equilateral triangle between the two posterior superior iliac spines and the hiatus (see Figure 8.2).

3. A “no-touch” technique or sterile gloves may be used after aseptic preparation of the area. Start by breaking the skin with an 18-gauge needle to avoid tracking an epidermal plug into the epidural space. Then insert a 22-gauge IV catheter into the sacrococcygeal ligament at a 60-degree angle to the skin. The bevel should be maintained in a ventral position to avoid puncture of the anterior wall of the sacrum. If bone is encountered, the needle is withdrawn several millimeters and the angle with the skin is decreased before advancing again. A distinct “pop” will be felt as the needle punctures the membrane; the needle and catheter are then dropped into a plane parallel to the spinal axis, and the needle shaft is advanced an additional 2 mm to be certain that the entire bevel of the needle is in the caudal space. Then the IV catheter is advanced gently into the caudal space, taking care not to puncture the dural sac.

Figure 21.1. Pediatric caudal anesthesia, lateral position. This technique is performed following the induction of general anesthesia and placement of an intravenous catheter. It is easily done in children in either the lateral or the prone position. The sacrococcygeal membrane is easily identified with the characteristic “pop,” and the injection is made after advancing the needle 1 to 2 mm.

4. Test dose. After negative aspiration for blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a test dose of the local anesthetic solution with epinephrine is injected (0.5 μg/kg) (17). Attention should be paid to the heart rate and ECG tracing for 1 minute. An increase of 10 beats/min suggests intravascular injection. The sensitivity of the test dose is diminished in the anesthetized patient. A transient elevation of the T waves, especially in V5, can also alert the provider to an intravascular injection of bupivacaine. The noninjecting hand can be placed superior to the injection site to detect any crepitance that occurs when the injection is subcutaneous rather than epidural.

5. Frequent aspiration and fractionated injection of local anesthetic is the best safeguard against undetected intravascular injection because test doses can be unreliable in children (13,18,19). Intraosseous injections into the marrow have rapid uptake similar to intravascular injections.

6. Caudal catheter. A 22-gauge catheter can be threaded through the 18-gauge IV to allow repeated boluses of local anesthetics in longer cases or for postoperative infusions. Before placement, the catheter should be measured to determine length from sacral hiatus to the desired dermatome. Catheter tip site can be confirmed with fluoroscopy or ultrasonography. A test dose should be done through the catheter before dosing it. In patients younger than 5 years, the catheter can usually be advanced to the thoracic level easily. Care should be taken with the dressing to minimize fecal soiling. A recommended infusion maximum of bupivacaine is 0.4 mg/kg/h, with even less in infants.

E. Complications

1. Dural puncture with resultant total spinal anesthesia is possible. Careful stabilization of the needle, careful advancement of the catheter, and frequent gentle aspiration will assist in avoiding this complication. A sacral dimple may be associated with spina bifida occulta and the risk of dural puncture may therefore be quite high.

2. Injection of local anesthetic intravascularly or intraosseous may lead to toxicity. Bupivacaine cardiac toxicity in children may be increased by the concomitant use of volatile anesthetics. The central nervous system (CNS) effect of the general anesthetic may obscure any signs of neurotoxicity until devastating cardiovascular effects are apparent. Dysrhythmias and cardiac arrest have occurred, usually in infants less than 10 kg. Extensive experience in older children before using this technique in infants is recommended.

3. Infection is possible but uncommon as most indwelling caudal catheters are removed within 2 to 3 days.

IV. Peripheral nerve blocks

The use of peripheral nerve blocks in children is growing with the increased manufacturing of pediatric-sized needles, catheters, and ultrasound probes.

A. Techniques

1. Nerve stimulator. Like in adults, a nerve stimulator is very helpful in placing these blocks. It is crucial to remember to avoid muscle relaxants before placing a block with a nerve stimulator in the anesthetized child.

2. Ultrasound -guided nerve blocks have increased in popularity in adult anesthesia. This device can be very helpful in nerve localization as well as visualizing the spread of local anesthetic in the desired tissue plane. It is increasingly being studied in children (20), but the technology requires significant training to master. Smaller “hockey-stick” probes are available that are more suited to the smaller anatomic relationships in children. Additional advantages of ultrasound-guided nerve blocks include requiring less volume of local anesthetic for an adequate block and potentially decreasing intravascular or intraneuronal injections.

B. Head and neck blocks. The use of nerve blocks for head and neck procedures is on the rise in pediatrics. Most are field blocks of sensory nerves with easily identified landmarks that can significantly improve postoperative pain management.

1. Supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve block

a. Anatomy. These are the end branches of the ophthalmic division (V1) of the trigeminal nerve. The supraorbital nerve exits the supraorbital foramen. The supratrochlear nerve exits 1 cm medially to the supraorbital nerve.

b. Indications. This block can be useful in frontal craniotomies, ventriculoperitoneal shunt revisions, and scalp nevus excision.

c. Technique. With the patient supine, palpate the supraorbital notch along the medial eyebrow in line with the midline pupil. Sterilely prepare the site. A 27-gauge needle is inserted just superior to the notch so as to avoid the artery that travels through it. Aspirate before placing 1mL of 0.25% bupivacaine. The needle is then withdrawn to skin level, redirected medially, and advanced several millimeters. Another 1 mL of bupivacaine is injected to block the supratrochlear nerve.

d. Complications. The vascular periorbital tissue has the potential for hematomas. Pressure applied to the injection site can minimize this.

2. Infraorbital nerve block. This simple block provides profound pain relief for 12 to 18 hours in children undergoing cleft lip or palate repair or other surgery on the anterior hard palate, lower eyelid, side of nose, or upper lip (21). Local anesthetic injected directly into the surgical site by the surgeon does not last as long as with this peripheral nerve block.

a. Anatomy. The infraorbital notch lies on a line connecting the supraorbital and mental foramina and the pupil of the eye (Figure 18.3).

b. Technique. There are two techniques for blocking this nerve, intraoral and extraoral. Both are field blocks and are not intended to be injected in the notch or in the nerve.

(1) Extraoral. First locate the infraorbital foramen with the index finger of the nondominant hand—approximately 0.5 cm from the midpoint of lower orbital margin. A 27-gauge needle is inserted at a 45-degree angle to the notch until touching bone. The needle is then withdrawn slightly so that the injection is not intraosseous, and 0.25 to 0.5 mL of local anesthetic is injected. A small skin wheal should be visible.

(2) Intraoral. The second technique is transoral and will leave no mark on the face. Again the infraorbital foramen is palpated with the nondominant hand. The superior lip is elevated and a 1.5-in. 25-gauge needle is inserted parallel to the upper incisor and guided toward the nondominant index finger palpating the notch. Inject 0.5 to 1.5 mL of local anesthetic. If this technique is planned, it should be performed before the surgery so that there is no risk of disruption of the surgery by the manipulation of the upper lip.

C. Rectus sheath block

1. Indications. This block can be used commonly in pediatrics, especially for surgeries around the umbilicus. It blocks the 10th intercostal nerves from both sides as they become the anterior cutaneous branch. The nerve passes between the transverse abdominus muscle and the internal oblique muscle, between the sheath and the posterior wall of the rectus abdominus muscle.

2. Technique. A 23-gauge needle is perpendicularly inserted above or below the umbilicus 0.5 cm medial to the linea semilunaris. The anterior rectus sheath can be appreciated by “scratching” the needle back and forth on it. Pass the needle through the anterior sheath and the muscle belly. Again the posterior sheath should be identified by a sensation of scratching on the sheath with the needle tip. Local anesthetic is deposited anterior to this posterior sheath to avoid intraperitoneal injection. The needle depth is usually 0.5 to 1.5 cm. Block placement can be facilitated by ultrasonography (22).

3. Drug. After negative aspiration, 0.25% bupivacaine can be injected, 0.2 mL/kg on each side.

4. Complications. Injection can be too superficial in the belly of the muscle and not spread posteriorly to the nerve, resulting in a failed block. Then also, an intravascular injection is possible in the belly of the muscle.

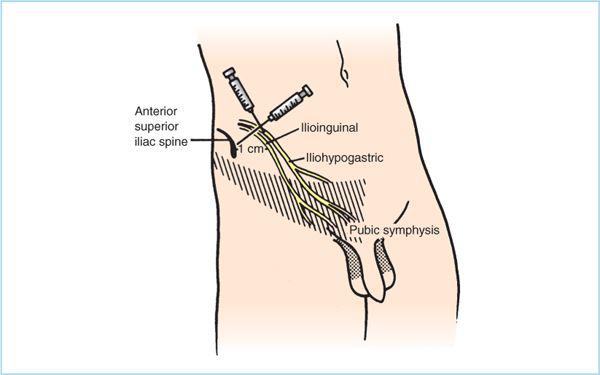

D. Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve block. This block provides analgesia equivalent to that of caudal blockade for children undergoing inguinal hernia, hydrocele, or orchidopexy repair. If there is a contraindication to a caudal, such as a sacral dimple, or the child is old enough to be disconcerted about the loss of leg strength postoperatively, this block is advantageous.

1. Technique. These nerves can be blocked by topical anesthetic into the wound, as described in the preceding text. A formal block of the nerves can be performed following induction of general anesthesia and before surgery as described in Figure 21.2 (23). An alternative technique, where the surgeon infiltrates the wound edges at the end of dissection (which also instills local anesthetic into the wound) is more effective than when the surgeon infiltrates the skin edges before closing the skin. This block can also be performed with ultrasound guidance (24).

2. Dose. Bupivacaine 0.25% is most often employed, in a dose of 5 to 10 mL depending on patient size. Ropivacaine 0.5% has also been used in children for this block.

3. Complications. Three percent to 5% of children receiving this block by techniques other than application of topical anesthesia may demonstrate transient blockade of the femoral nerve, with temporary inability to stand due to loss of quadriceps strength.

E. Penile blocks. This block is useful for perioperative analgesia for boys undergoing circumcision or hypospadias repair. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics does not endorse circumcision, it does endorse the use of local anesthetics if the family desires a circumcision in the neonatal period. Both the topical application of EMLA cream and the ring block of the penis are simple and have minimal risk to the newborn.

Figure 21.2. Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric block. A 23- to 25-gauge needle is inserted 1 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, and a wall of anesthesia is created by injecting in a fan-like manner along the muscle wall from the ilium to the border of the rectus. A total of 5 to 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine will provide anesthesia for the ilioinguinal (crosshatched) and the iliohypogastric (stippled) innervation. (Adapted from Yaster M, Maxwell LG. Pediatric regional anesthesia. Anesthesiology 1989;70:324, with permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree