INTRODUCTION

NEWBORN CONDITIONS: ERYTHEMA TOXICUM NEONATORUM

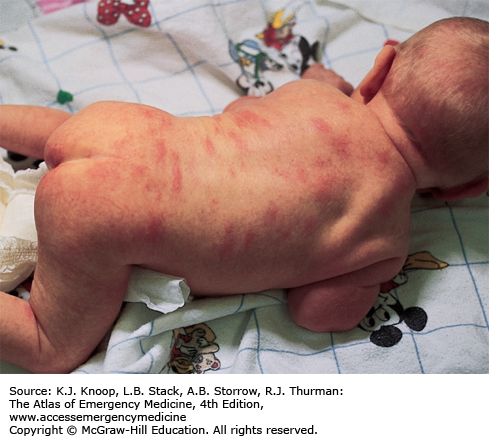

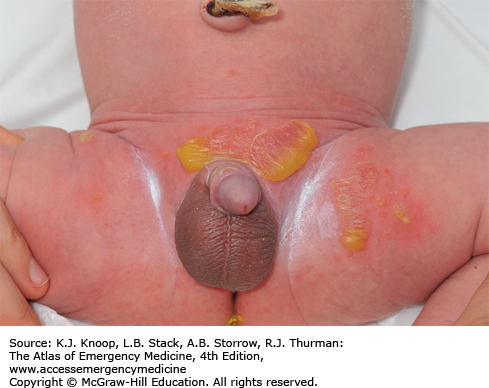

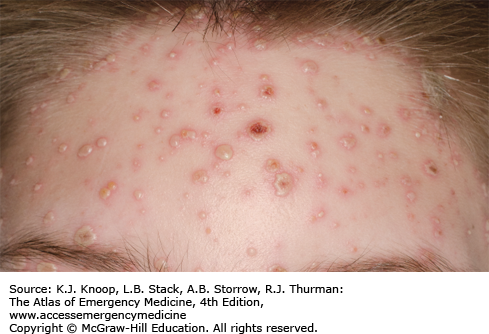

Erythema toxicum neonatorum is a benign, self-limited vesicopustular lesion of unknown etiology that occurs in up to 70% of term newborns. It is characterized by discrete, small, erythematous macules or patches up to 2 to 3 cm in diameter with 1 to 3 mm firm pale yellow or white papules or pustules in the center. The trunk and proximal extremities are predominantly involved. This rash usually appears within the first 24 to 72 hours of life but may be present at birth. The distinctive feature of erythema toxicum is its evanescence, with each individual lesion usually disappearing within 5 to 7 days. New lesions may occur in a waxing and waning fashion. The diagnosis is usually made based on the clinical appearance of the rash in an otherwise well-appearing neonate without any systemic signs of illness. Wright-stained slide preparations of a scraping from the center of the lesion demonstrate numerous eosinophils. Cultures from these lesions will be negative. The differential diagnosis includes neonatal acne, transient neonatal pustular melanosis, newborn milia, miliaria, infantile acropustulosis, neonatal herpes simplex, bacterial folliculitis, candidiasis, and impetigo of the newborn.

No specific therapy is indicated in the setting of a well-appearing newborn with normal activity and appetite. Parents should be educated and reassured about the evanescence of the rash. In cases where impetigo, Candida, or herpes infections are suspected, a smear from the center of the lesion and bacterial and viral cultures may be necessary to make a final diagnosis.

Erythema toxicum is the most common newborn rash.

The lesions may present anywhere on the body but tend to spare the palms and soles.

Laboratory evaluation is unnecessary.

SALMON PATCHES (NEVUS SIMPLEX)

Nevus simplex (salmon patch) is the most common vascular lesion in infancy, present in about 40% to 60% of newborns. It appears as a blanching, slightly pink-red macule or patch most commonly on the nape of the neck, the glabella, mid-forehead, or upper eyelids. Lesions generally fade over the first 2 years of life but may become more prominent with crying or straining.

Parental education and reassurance can be helpful, but no immediate treatment is indicated. Pulsed dye laser may be considered for persistent lesions that are cosmetically undesirable.

Salmon patches are composed of ectatic dermal capillaries.

Salmon patches appear symmetrically and cross the midline in contrast to the unilateral distribution of a port-wine stain.

When seen on the nape of the neck, this lesion is referred to as a stork bite or as an angel’s kiss when appearing on the forehead.

About 5% of those appearing at the nape of the neck will remain permanently or recur.

Obtain imaging to evaluate for spinal dysraphism in patients with a lumbosacral nevus simplex and another lumbosacral abnormality (dermal sinus or pit, patch of hypertrichosis, or deviated gluteal cleft).

NEONATAL JAUNDICE

Neonatal jaundice is the yellowing of the skin, sclerae, and/or mucous membranes caused by bilirubin deposition. It occurs when total serum bilirubin is in excess of 5 mg/dL and progresses in a head-to-toe fashion as levels increase. Most cases of physiologic (<12 mg/dL) jaundice are self-limited without sequelae, and appear on the second or third day of life peaking between the third and fifth day. Preterm infants may peak later.

The increased bilirubin production in newborns is a result of turnover of fetal red blood cells, a temporary decrease in conjugation and clearance by the immature newborn liver, and increased enterohepatic circulation. Risk factors for indirect hyperbilirubinemia include maternal diabetes, prematurity, drugs, polycythemia, traumatic delivery with cutaneous bruising or hematoma, breastfeeding, and ABO (O mother and A/B infant) or Rh(D) incompatibility (Rh(D) negative mother and Rh(D) positive infant). Most infants with jaundice have no “disease” per se, but a careful history and organized approach is necessary to identify potentially pathologic causes. Kernicterus manifests in a multitude of irreversible neurologic abnormalities and is the long-term result of bilirubin-induced neurologic dysfunction secondary to extreme unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia which leads to neuronal death and pigment deposition in the basal ganglia and cerebellum.

Initial laboratory workup should include blood type, Coombs test, complete blood count (CBC) with smear for red cell morphology, reticulocyte count, and indirect and direct bilirubin levels. Although transcutaneous bilirubin measurement devices are widespread, they can underestimate total bilirubin at levels >15 mg/dL; therefore, a serum measurement is recommended for severely jaundiced newborns. Initial management should ensure adequate hydration and treatment of the underlying condition. The level of serum bilirubin at which to start phototherapy can be obtained from a standardized nomogram and is dependent upon the infant’s postnatal age in hours, gestational age, and an assessment of risk factors. In general, the goal of phototherapy is to maintain the bilirubin level below 20 mg/dL. Exchange transfusion is considered if the serum level remains elevated (22-25 mg/dL) despite appropriate phototherapy.

Onset of clinical jaundice in the first 24 hours of life strongly suggests the presence of a pathologic process.

Direct serum bilirubin concentration exceeding 10% of total serum bilirubin or 2 mg/dL suggests hepatobiliary disease or a metabolic disorder.

Bilirubin levels at which to initiate phototherapy or exchange transfusion should be modified for prematurity, sepsis, low birth weight, and other risk factors.

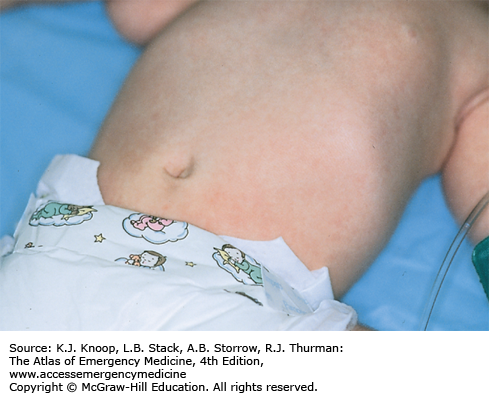

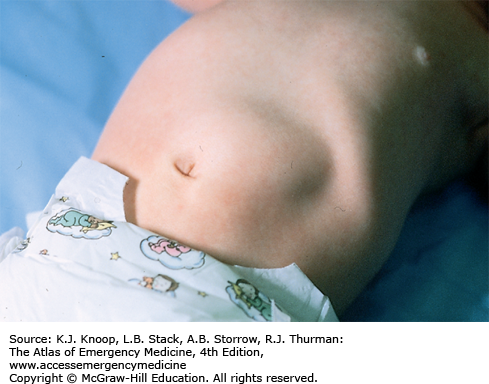

NEONATAL MILK PRODUCTION (WITCH’S MILK)

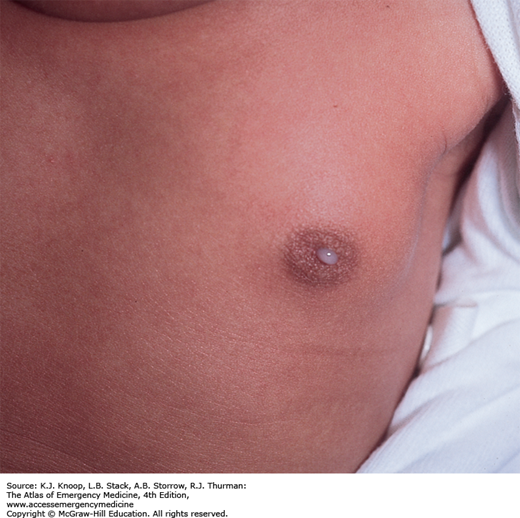

Neonatal galactorrhea occurs in up to 6% of term newborns and is usually secondary to transplacental transfer of maternal estrogen. These hormonal effects (maternal estrogens and endogenous prolactin) lead to palpable breast buds in approximately one-third of all term newborns. Males and females are equally affected. In most cases, the breast enlargement and galactorrhea begin to subside after the second week of life in males and 2 to 6 months in females. Infants with neonatal breast hypertrophy may be predisposed to infections (mastitis or abscess) possibly incited by repetitive manipulation of the enlarged breast bud by a caregiver. The differential diagnosis includes early mastitis with purulent nipple discharge.

Treatment is not necessary unless infection is suspected. Parents can be reassured that this is a normal finding, and follow-up to resolution should occur at routine well child care visits.

Classical presentation includes the presence of clear colostrum-like secretions in newborns with hypertrophied mammary tissue without erythema or tenderness. Persistence of enlarged breast buds beyond 6 months of age should prompt follow-up with a pediatric endocrinologist.

In an older child, galactorrhea may be the presenting sign of hypothyroidism or pathologically elevated prolactin levels.

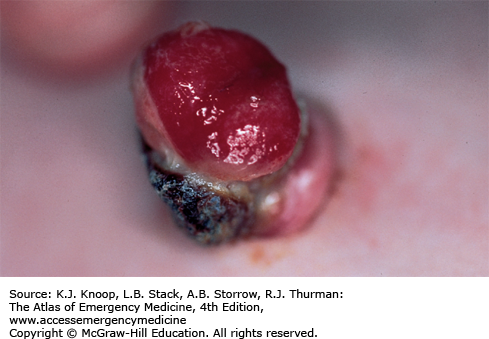

NEONATAL MASTITIS

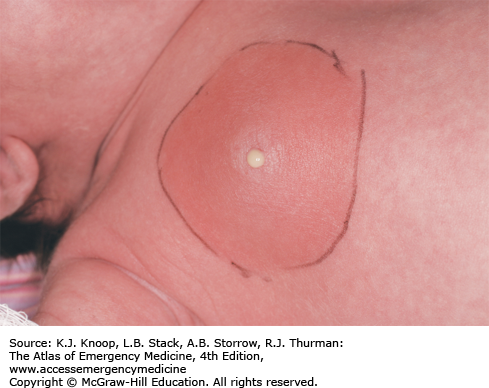

Neonatal mastitis is an infection of the breast tissue that occurs in full-term neonates with a peak incidence in the third week of life. Females are affected more often than males in a 2:1 distribution. Clinically, it manifests as swelling, induration, erythema, warmth, and tenderness of the affected breast. The ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes may be swollen. Approximately two-thirds have palpable fluctuance. In some cases, purulent discharge may be expressed from the nipple. Fever may be present in 25% of affected patients. Other systemic symptoms (irritability, decreased appetite, and vomiting) are less common but indicate a more severe infection if present. Bacteremia is rare. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen, causing 75% to 85% of cases. Rarely, gram-negative organisms or group B or D Streptococcus are the cause. If treatment is delayed, mastitis may progress rapidly with involvement of subcutaneous tissues and subsequent toxicity. In the initial stages, neonatal mastitis may mimic mammary tissue hypertrophy owing to maternal passive hormonal stimulation. Minor trauma, cutaneous infections, and duct blockage may precede this infection.

Immediate treatment is important to avoid cellulitic spread and breast tissue damage. In cases of mild cellulitis with no associated fluctuance in an otherwise well-appearing, afebrile neonate, culture of nipple discharge (if present) and oral antibiotics (antistaphylococcal penicillin or first-generation cephalosporin) with close outpatient follow-up are sufficient. Adjustment of coverage can be made once results of cultures or Gram stain are available, especially in the presence of gram-negative bacilli. In cases involving systemic signs of infection, rapid subcutaneous spread, or toxic appearance, a complete sepsis workup should be performed followed by hospitalization. If no organism is seen on Gram stain, a parenteral antistaphylococcal penicillin plus an aminoglycoside or cefotaxime alone should be used. In cases of palpable fluctuance, prompt surgical consultation should be obtained to assess the need for needle aspiration or incision and drainage. Conservative treatment with intravenous (IV) antibiotics often results in resolution of the fluctuance without surgical intervention. Recovery is usually within 5 to 7 days.

Antibiotic choice should include coverage for S aureus.

Maintain a low threshold for initiating a sepsis workup and IV antibiotics.

Delays in the diagnosis and treatment may lead to distortion of the nipple, impairment of the secretory capacity of the breast, and reduction in the size of the adult breast.

An umbilical granuloma is granulation tissue with incomplete epithelialization that persists following cord separation. It is the most common cause of an umbilical mass in neonates. Parents will describe a persistent discharge from the umbilicus after the cord has dried and separated. It appears soft, pink, wet, and friable. Infants with an umbilical granuloma do not have localized swelling, redness, warmth, tenderness, or fever. An umbilical polyp is a rare anomaly resulting from the persistence of the omphalomesenteric duct or the urachus and may have a similar appearance. A polyp is usually firm with a mucoid secretion. The differential diagnosis also includes omphalitis, an infection of the umbilicus and surrounding structures, which should be considered in ill-appearing neonates.

Advise parents to keep the granuloma dry and exposed to the air as often as possible. Cleaning and drying of the umbilical cord base with alcohol is not necessary and may irritate the skin and delay healing. Cauterization of the granuloma by application of topical silver nitrate is the treatment of choice. It is important to protect the surrounding skin (apply petroleum jelly or antibiotic ointment) and remove excess silver nitrate to avoid chemical burns and skin staining. The cauterization may need to be repeated at 3-day intervals if drainage persists.

An umbilical granuloma is the most common umbilical mass in neonates.

The only sign of granuloma formation may be the presence of nonpurulent discharge noted in the diaper area that is in contact with the umbilicus.

Omphalitis presents with redness of the periumbilical area typically tracking upward in the midline and often with a purulent discharge from the umbilicus. It can progress to abdominal wall cellulitis or peritonitis and requires a complete sepsis workup and hospital admission for treatment with broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is characterized by progressive postprandial, nonbilious vomiting that steadily increases in frequency and amount due to hypertrophy of the pyloric musculature and edema of the pyloric canal, producing gastric outlet obstruction. It is usually diagnosed in infants from birth to 5 months, most commonly at 2 to 8 weeks of life. The vomiting may become forceful and is then described as projectile (although this pattern is not always present). There is a familial tendency, and white males (especially firstborn) are more frequently affected. During the physical examination, peristaltic waves may be observed traveling from the left upper to right upper quadrants. The hypertrophy of the antral and pyloric musculature produces the “olive” to palpation (best palpated in the epigastrium or right upper quadrant after emesis or emptying the stomach with a nasogastric tube). As a result of persistent vomiting, hypochloremic, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis with varying degrees of dehydration, and failure to thrive may occur when the diagnosis is not made early in the course.

The finding of a pyloric olive on palpation of the abdomen is pathognomonic. Ultrasound is a useful tool to confirm the diagnosis when the olive is not evident on examination or early in the course. The differential diagnosis includes intestinal obstruction or atresia, malrotation with volvulus, hiatal hernia, gastroenteritis, adrenogenital syndrome, increased intracranial pressure, esophagitis, sepsis, gastroesophageal reflux, and poor feeding technique.

Treatment includes correction of electrolyte imbalances and dehydration, as well as emergent surgical consultation for curative Ramstedt pyloromyotomy. Failure to correct metabolic alkalosis prior to surgery can increase the risk of postoperative apnea. Patients may benefit from a nasogastric tube on low intermittent suction.

HPS is the most common cause of metabolic alkalosis in infancy.

Serial examinations and observation of the child after oral fluid challenges for persistent projectile vomiting may aid in making the diagnosis.

Clinical manifestations of pyloric stenosis begin at a mean age of 3 weeks after birth.

Pyloric ultrasonography is the diagnostic study of choice.

Less than 2% of infants with HPS have bilious vomiting.

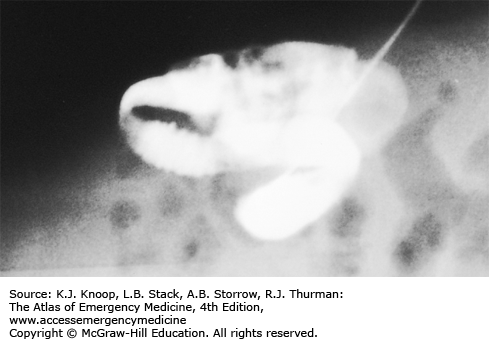

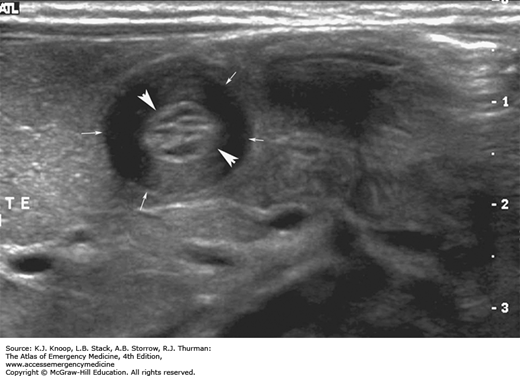

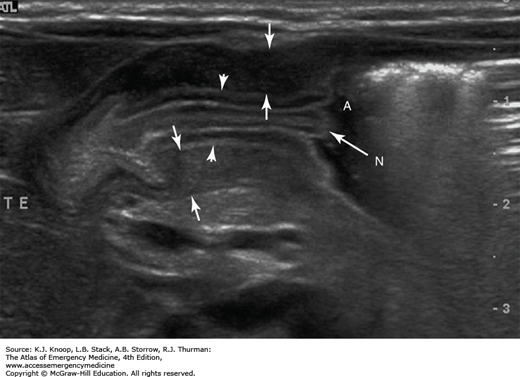

FIGURE 14.15

Antral Nipple Sign in HPS. This longitudinal sonogram shows two-layered, thickened mucosa (arrowheads) surrounded by muscular components (arrows). Redundant pyloric mucosa protrudes into the fluid in the gastric antrum (A), forming the “antral nipple sign” (N) in HPS. (Photo contributor: Lawrence B. Stack, MD.)

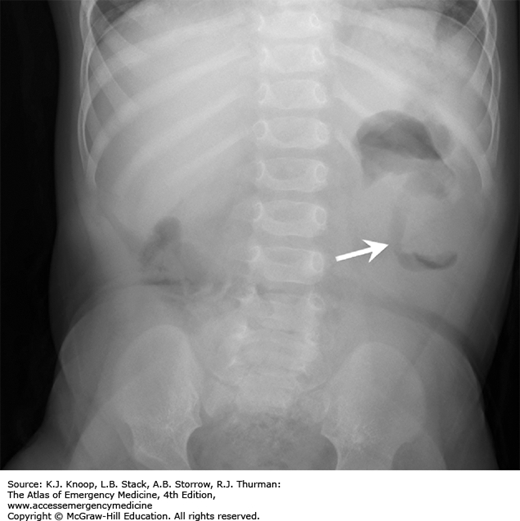

Intestinal malrotation is primarily a condition of infancy but can be seen in older children and adults. During the fourth week of embryonic development, the primary intestinal loop bulges into the yolk sac, rotates 270 degrees counterclockwise, and returns to the enlarged abdominal cavity between the eight and tenth week where it is fixed via mesentery that extends from the ligament of Treitz to the ileocecal valve in the right lower quadrant. In malrotation, the duodenum, jejunum, and cecum are partially rotated with the bowel anchored by an abnormally thin band of mesentery. The bowel can twist on this thin mesentery, which contains the superior mesenteric artery, leading to acute intestinal obstruction and midgut vascular compromise known as volvulus. Also, the abnormally positioned cecum now rests in the upper abdomen fixed to the right lateral abdominal wall by bands of peritoneum (Ladd bands) that cross and can obstruct the duodenum.

Presentation is with vomiting in 50% of cases. The vomiting may not be bilious, but it is classically described as such. Patients are often irritable with significant abdominal tenderness. Third space fluid losses increase as gut ischemia progresses. Differential diagnosis includes pyloric stenosis, intestinal atresias, appendicitis, necrotizing enterocolitis, and intussusception.

Emergent surgical consultation is indicated. Plain x-rays are rarely diagnostic, but may show signs of small bowel obstruction. An upper gastrointestinal (GI) series is the most helpful study, though one-quarter of cases may have an equivocal result. Preoperative management consists of resuscitation with IV fluids, placing a gastric tube for decompression, and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Fifty percent of patients with malrotation present with volvulus in the first month of life.

Over 30% of cases of malrotation with volvulus present beyond early childhood usually with an insidious onset with abdominal pain as the most common symptom.

The imaging test of choice is the upper GI series, but computed tomography (CT) should be considered in ill-appearing patients in which administration of enteral contrast may be difficult.

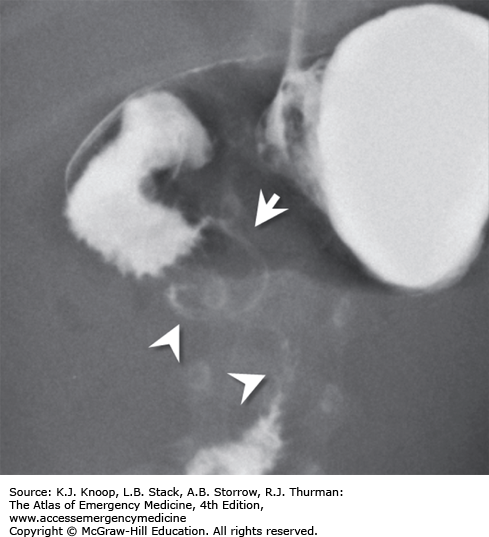

FIGURE 14.17

Intestinal Malrotation with Volvulus. Anteroposterior radiograph from an upper GI series shows malrotation with midgut volvulus. The duodenum (arrowheads) does not cross midline and does not extend superiorly to the level of the pylorus. The spiraling downward appearance is consistent with volvulus. (Photo contributor: Alexander Towbin, MD.)

Erythema infectiosum is a viral infection caused by parvovirus B19, presenting most commonly between 4 and 10 years of age. It begins with nonspecific prodromal symptoms including malaise, coryza, headache, fever, nausea, and diarrhea. Two to 5 days into the illness, the classic rash appears characterized initially by the “slapped cheeks” appearance of a bright red malar macular rash that spares nasal ridge and perioral areas. A reticulated, lacy erythematous maculopapular eruption with central clearing then appears on the extensor surfaces of extremities. The differential diagnosis includes other morbilliform eruptions such as measles, rubella, roseola, and infectious mononucleosis. Bacterial infections (eg, scarlet fever), drug reactions, and other skin conditions such as guttate psoriasis, papular urticaria, atopic dermatitis, and erythema multiforme are also included in the differential.

Treatment is aimed at symptomatic relief. Parents can be reassured that this exanthem is benign and self-limited. Once the rash appears, the patient is no longer contagious. It is important to educate the patient and family about the possible risk of parvovirus B19 as a cause of hydrops fetalis or fetal deaths early in pregnancy. It can also cause an aplastic crisis in patients with hematologic conditions such as sickle cell disease, hereditary spherocytosis, and various hemolytic anemias, or in the immunocompromised.

Recrudescence of the lacy, reticular rash may occur with exercise, overheating, emotional upset, or sun exposure as a result of cutaneous vasodilatation.

Parvovirus B19 is the most common cause of hydrops fetalis. Pregnant mothers of children diagnosed with erythema infectiosum should have their serologic status determined.

In young adults, parvovirus B19 can cause papular purpuric gloves and socks syndrome.

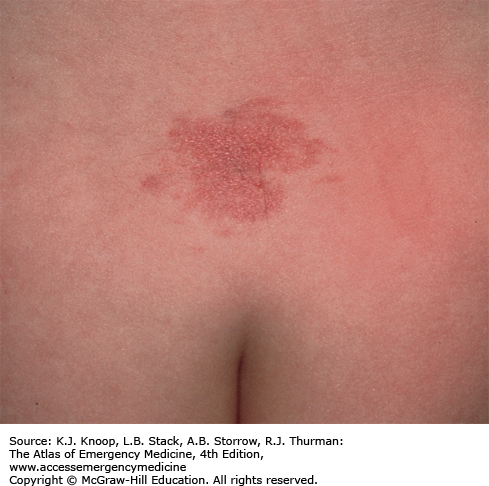

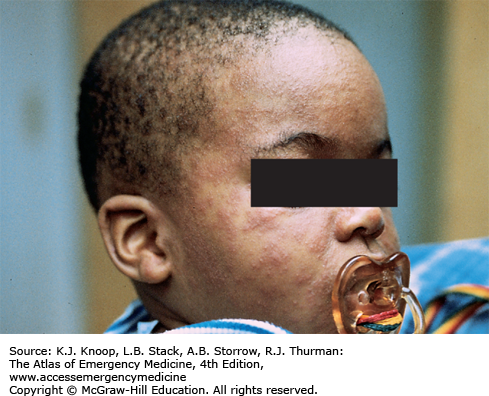

The typical presentation of roseola infantum involves a prodrome characterized by a 3- to 5-day history of high fever often exceeding 40°C (104°F) in a child 6 months to 3 years of age. The child may be fussy, but is often otherwise well-appearing. After the child’s fever abates, the typical exanthem appears characterized by blanching erythematous macules and papules on the trunk, neck, proximal extremities, and occasionally the face. The rash fades within 2 to 4 days, but may only last several hours. The causative agent in 90% of cases is human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6). The differential diagnosis includes viruses such as measles, rubella, parvovirus B19, or infectious mononucleosis. Bacterial infections (eg, scarlet fever), drug reactions, and other skin conditions such as guttate psoriasis, papular urticaria, and erythema multiforme are also included in the differential.

As with most viral infections, only supportive therapy is necessary. Special attention should be paid in maintaining fluid intake, fever control for the patient’s comfort, and parental education about the benign, self-limited nature of this illness.

With defervescence and appearance of the rash, the patient is no longer contagious.

The most frequent complication of roseola is febrile seizures.

Impetigo is a contagious bacterial infection of the superficial skin that is caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus) and S aureus. It most commonly affects children 2 to 5 years of age and usually involves the face and extremities. It begins as small vesicles or pustules with very thin roofs that rupture easily with the release of a cloudy fluid and subsequent formation of honey-colored crusts. Variants include bullous impetigo and the ulcerative form. The lesions may spread rapidly by autoinoculation secondary to scratching and coalesce to form larger areas of infection. The differential diagnosis includes second-degree burns, varicella, herpes simplex infections, nummular dermatitis, superinfected eczema, and scabies.

These lesions are highly contagious and spread by direct contact. Hand washing and personal hygiene should be emphasized to the patient and family. Application of topical antibacterials, such as mupirocin ointment, has proven to be as effective as oral antibiotics if there are a limited number of lesions and no bullae. Over-the-counter triple antibiotic ointments (bacitracin-neomycin-polymyxin B) may not be as effective. If lesions are extensive and/or bullous, oral antibiotic coverage is indicated. Effective oral agents include first-generation cephalosporins, dicloxacillin, amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, or clindamycin.

Inflicted cigarette burns may resemble the lesions of impetigo.

Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and rheumatic fever can be complications of impetigo caused by group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus.

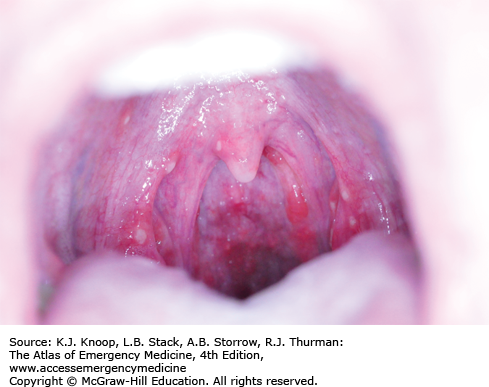

Measles presents as an acute febrile illness with a 3- to 4-day prodromal period characterized initially by fever, malaise, and anorexia, followed closely by conjunctivitis, coryza, and cough. Koplik spots, the pathognomonic enanthem of measles, appear as 1- to 3-mm red papules with gray-white centers on the buccal mucosa. They usually present approximately 48 hours before the development of the characteristic erythematous blanching maculopapular rash. This rash appears during the third or fourth day of the illness as dark red to purple macules and papules on the forehead, around the hairline, behind the earlobes, subsequently spreading in a cephalocaudad progression. Individual lesions often become confluent. The lesions tend to fade in the same order that they appear.

Most cases recover without complications; others may develop otitis media, croup, pneumonia, encephalitis, myocarditis/pericarditis, keratitis, and rarely subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a very late complication. The differential diagnosis of the characteristic rash is vast and includes exanthem subitum, rubella, infections caused by echovirus, coxsackie and adenoviruses, toxoplasmosis, infectious mononucleosis, scarlet fever, Kawasaki disease, drug reactions, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and meningococcemia.

Supportive therapy includes bed rest, antipyretics, and adequate fluid intake. Complications should be treated accordingly. Currently available antivirals are not effective. Postexposure prophylaxis includes administration of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine within 72 hours of exposure to a patient with active measles. Passive immunization with intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) is effective for prevention and attenuation of measles if given within 6 days of the initial exposure especially in pregnant women and the immunocompromised. During outbreaks, MMR vaccine can be given to infants younger than 12 months. However, such infants require an additional two doses of MMR at the recommended ages after their first birthday.

Measles is now rare in the United States but remains endemic in other parts of the world.

MMR vaccine is preferable to IVIG as postexposure prophylaxis.

Morbilliform means measles-like.

Chickenpox results from primary infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV) and is characterized by a generalized pruritic vesicular rash, fever, and mild systemic symptoms. Fifteen days after exposure and following a prodrome of fever, malaise, pharyngitis, and/or loss of appetite, the characteristic generalized pruritic vesicular rash develops. The lesions usually develop 24 hours after the onset of illness, appear in crops, start on the trunk and spread peripherally, and evolve from erythematous, pruritic macules to papules and vesicles (rarely bullae) that finally crust over within 48 hours. The classic lesions are teardrop vesicles surrounded by an erythematous ring (“dewdrop on a rose petal”). The most common complication of varicella is secondary bacterial skin infection, usually with S pyogenes or S aureus. Other complications from varicella include encephalitis, glomerulonephritis, hepatitis, pneumonia, arthritis, and meningitis. Cerebellitis (manifested clinically as ataxia) may develop and is usually self-limited. Other viral infections that may manifest with vesicular rashes include herpes simplex, zoster, coxsackie, influenza, echovirus, and vaccinia. On occasion, varicella can be confused with papular urticaria.

Suspected varicella infection should lead to strict isolation early in the emergency department or office encounter. Most children have a self-limited illness and do not develop any complications. Treatment should be supportive and directed to pruritus and fever control while avoiding salicylates because of their association with Reye syndrome. Oral acyclovir initiated within 24 hours of the onset of the rash may result in a modest decrease in the duration of symptoms and in the number and duration of skin lesions. Acyclovir is not recommended routinely for treatment of uncomplicated varicella in an otherwise healthy child less than 12 years of age. In the immunocompromised host, varicella zoster immunoglobulin (VZIG), IV acyclovir, and hospital admission are indicated.

Skin lesions in varicella present in successive crops so that macules, papules, vesicles, and crusted lesions may all be present at the same time.

Healthy children are no longer contagious when all lesions have crusted over (usually 4-5 days from the development of the initial lesions).

Consider oral acyclovir for those at risk for more severe infection, including anyone older than 12 years, with chronic diseases, and taking chronic aspirin or corticosteroid therapy. Postexposure prophylaxis includes VZIG within 96 hours of exposure in high-risk patients (immunocompromised patients or pregnant women) or immunization with varicella vaccine within 72 hours of exposure in non–high-risk patients.

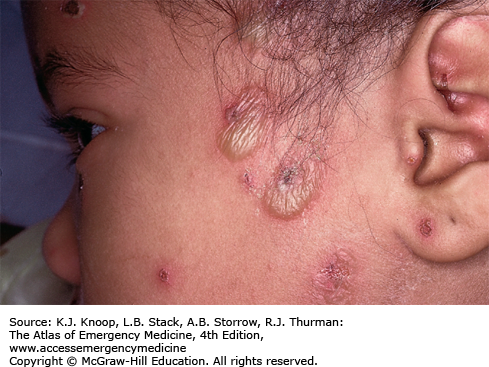

Zoster (shingles) represents a reactivation of latent VZV and has been noted as early as the first week of life in infants born to mothers who contracted varicella during pregnancy. The lesions present as clustered vesicles or bullae in a dermatomal distribution. The pain of acute neuritis occurs in 75% of patients with herpes zoster. Prodromal pain can be constant or intermittent, burning or stabbing and can precede the lesions by days to weeks. Sometimes pain can persist beyond 1 month after the lesions have disappeared (known as postherpetic neuralgia).

The diagnosis is usually made clinically; however, tissue cultures, direct fluorescent antibodies, and Tzanck smears can be done from vesicle scrapings for confirmation. Impetigo and cutaneous burns may mimic the appearance of herpetic vesicles. Varicella (chickenpox) is more diffusely spread, although a small crop of lesions may mimic zoster. Zoster also may be confused with herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, although a close examination should reveal a dermatomal distribution in zoster.

Currently, acyclovir (800 mg orally five times per day for 7-10 days initiated within 48 hours of the onset of the rash in children ≥12 years) is the treatment of choice for zoster infections in immunocompetent children. Pain relief and prevention of secondary infection are also important. IV antiviral therapy is recommended for immunocompromised patients. There is no pediatric formulation of famciclovir or valacyclovir, and there are insufficient data on their use in children.

Zoster can occur in children of all ages.

The most common sites for the development of zoster lesions are those supplied by the trigeminal nerve and the thoracic ganglia.

A patient with zoster can transmit chickenpox (varicella) to a nonimmune child or adult.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is a sight-threatening condition that presents with hyperesthesia in the effected eye. Vesicular lesions on the nose (Hutchinson sign) are associated with an increased risk of eye involvement.

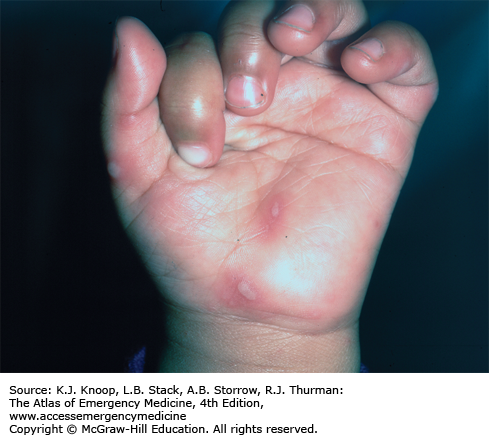

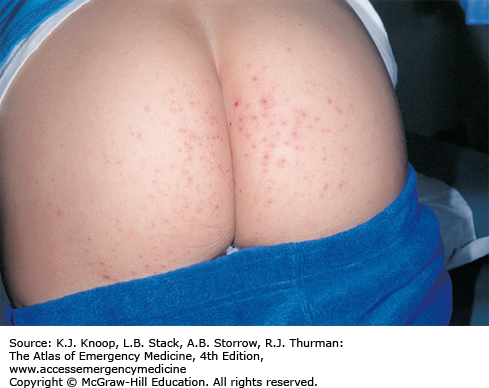

Hand, foot, and mouth syndrome is a seasonal (summer-fall) viral infection caused by coxsackievirus A16. Toddlers and school-aged children are affected most commonly. Adults may also be affected. It is characterized by a prodrome of fever, malaise, sore throat, and anorexia over 1 to 2 days, followed by the appearance of the characteristic enanthem in the posterior oropharynx and tonsillar pillars consisting of small, red macules evolving into small vesicles 1 to 3 mm in diameter that rapidly ulcerate. Oral manifestations are followed by a vesicular eruption characterized by 3- to 7-mm erythematous macules with a central gray vesicle on the hands and feet involving the palmar and plantar surfaces and interdigital surfaces. Nonvesicular rash may also be present on the buttocks, face, and legs.

Supportive therapy (hydration maintenance with fever and pain control) is the mainstay of treatment. Discuss the duration and characteristics of the illness with the parents. In most cases, the course is self-limited resolving in 2 to 3 days after the appearance of rash without further complication. Rare secondary complications such as myocarditis, pneumonia, pulmonary hemorrhage, and meningoencephalitis may occur.

The child is contagious until all vesicles have resolved.

The oral lesions tend to involve the posterior oropharynx as contrasted with those of herpetic gingivostomatitis which typically involve the anterior structures of the mouth.

Varicella vesicles are located more centrally, are more extensive, and usually spare the palms and soles.

FIGURE 14.35

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease. Nonvesicular rash on the buttocks, a common site. (Photo contributor: Binita R. Shah, MD. Used with permission from Shah B, Lucchesi M, Amodio J, Silverberg M. Atlas of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013: Fig. 3.66D, p. 111.)

Cold panniculitis represents acute cold injury resulting in inflammation of the subcutaneous fat. It manifests as erythematous, indurated nodules, and plaques on exposed skin, especially the perioral areas and cheeks. Lesions appear 24 to 72 hours after exposure to cold and gradually soften and return to normal over 1 to 2 weeks usually without permanent sequelae. This phenomenon is caused by subcutaneous fat solidification and necrosis following exposure to cold temperatures. It is much more common in infants. The differential diagnosis includes facial cellulitis, frostbite, trauma, pressure erythema, giant urticaria, and contact dermatitis.

Treatment is supportive. Parental education and reassurance is important.

Because these lesions may also be painful, the differentiation of cold panniculitis from cellulitis may be difficult. The absence of systemic symptoms, especially fever, and the history of cold exposure are more suggestive of cold panniculitis.

The lesions may resolve with resulting hyperpigmentation of the affected area.

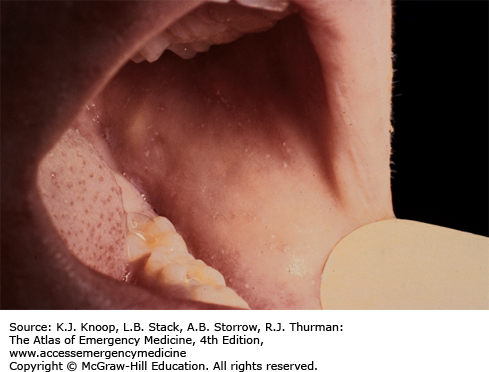

Herpetic gingivostomatitis is primary infection caused by HSV seen in up to 30% of children between 6 months and 5 years of age. Patients usually present with approximately 4 days of fever, malaise, decreased oral intake, cervical adenopathy, and pain in the mouth and throat. Following the prodrome, vesicular and ulcerative lesions appear throughout the oral cavity. The gingiva becomes very friable and inflamed, especially around the alveolar rim. Increased salivation, foul breath, and cervical lymphadenitis may be present. Although fever resolves in 3 to 5 days, children may have difficulty eating for 7 to 14 days. Sometimes, autoinoculation produces vesicular lesions on the fingers (herpetic whitlow).

Treatment includes pain control, hydration, and consideration of oral acyclovir therapy. The pain may be significant and often requires oral narcotic pain medications. Control of the pain will allow the patient to consume fluids and remain well hydrated. Acyclovir has been shown to reduce the duration of pain, gingival swelling, oral lesions, fever, and viral shedding if initiated within the first 72 to 96 hours of illness. Avoidance of citrus juices or spicy food is recommended. Cold clear fluids, popsicles, and ice cream may be useful in small children. Not infrequently, admission for IV hydration is necessary. Topical pain control may be achieved by using mixtures of antihistamine (diphenhydramine elixir) and antacid (1:1) applied to lesions with a cotton swab. Local application of viscous lidocaine should be avoided in children, since patients may develop toxic serum levels due to altered absorption from inflamed oral mucosa leading to seizures.

Most lesions are in the anterior two-thirds of the oral cavity. Posterior lesions sparing the gingiva are most commonly seen in coxsackievirus infections.

Primary HSV infection in childhood is usually asymptomatic.

After primary oral infection, HSV remains latent in the trigeminal ganglion until reactivation as herpes labialis.

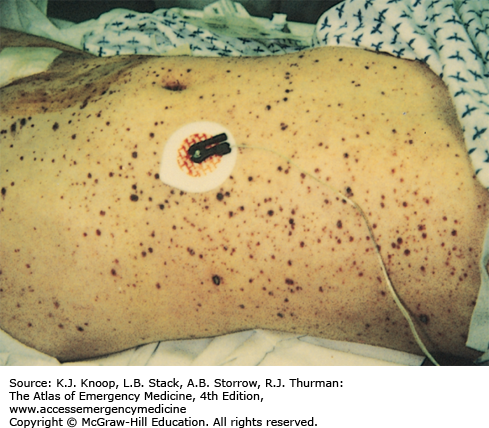

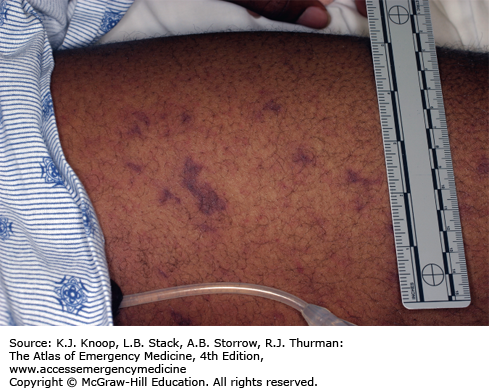

Meningococcemia is an acute febrile illness caused by Neisseria meningitidis bacteremia characterized by its generally rapid onset, significant toxicity, and petechial rash involving the skin and mucous membranes. The petechiae progress to become palpable purpura and may coalesce to become purpura fulminans. It progresses rapidly to decompensated septic shock with hypotension and multisystem organ failure. In cases of fulminant disease, progressive shock is accompanied by disseminated intravascular coagulation and massive mucosal hemorrhages. Prodromal symptoms may include cough, coryza, headache, neck pain, and malaise. Children less than 5 years of age and college students not receiving the meningococcal vaccine during high school are at greatest risk.

In stable patients in which meningococcemia is in the differential diagnosis, obtain cultures of blood and spinal fluid and from the nasopharynx, along with a CBC and coagulation studies. Consider bedside screening studies (eg, blood gas to assess acid-base status), liver function tests, and other studies as clinically indicated. These patients should be admitted for intensive monitoring to institutions capable of delivering critical care services. Broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics should be administered initially until the organism is identified and sensitivities are available as with any patient with suspected sepsis. In the unstable septic patient, support end organ perfusion and oxygenation via early goal-directed therapy. Hemodynamic monitoring and blood pressure support (fluids and vasoactive drugs) are of paramount importance. Peripheral and central venous catheters and urinary and arterial catheters are usually necessary for optimal management of these patients.

Skin scrapings of the purpuric lesion can be cultured and microscopically examined for the presence of gram-negative diplococci.

A child with a fever and an evolving petechial rash is presumed to have meningococcemia until proven otherwise.

A quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine is now available and recommended for all adolescents between ages 11 and 12 and then again at age 15 years or high school entry (whichever comes first).

Prophylaxis for all close contacts is recommended with rifampin for 48 hours or a single dose of ceftriaxone or ciprofloxacin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree