Fig. 36.1

(a) MRCP image reveals a dilated duct (long arrow) abruptly terminating as it descends into the pancreatic head. Presence of tumor hinted at by the cluster of minute cystic spaces (short arrow). (b, c) Axial and coronal enhanced images show the hypoenhancing tumor (short arrows) broadly abutting the superior mesenteric vein (long arrow) (S SMA). (d) Axial diffusion-weighted image highlights the mass (arrow)

Fig. 36.2

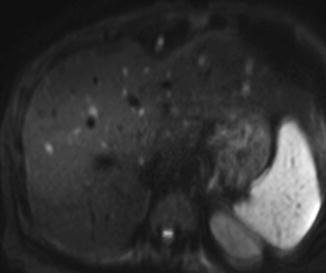

A diffusion-weighted image (DWI) from a staging MRI revealing a number of hepatic metastases from pancreatic adenocarcinoma. DWI phase is extremely sensitive for liver metastases as these lesions were not discernible on triple phase pancreas protocol CT or PET/CT

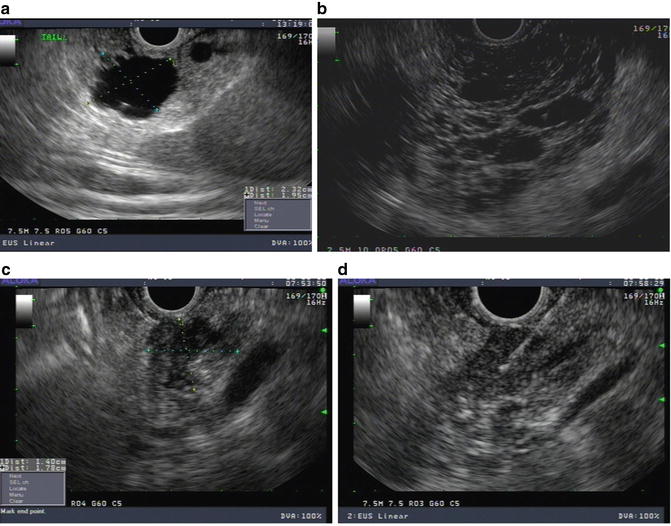

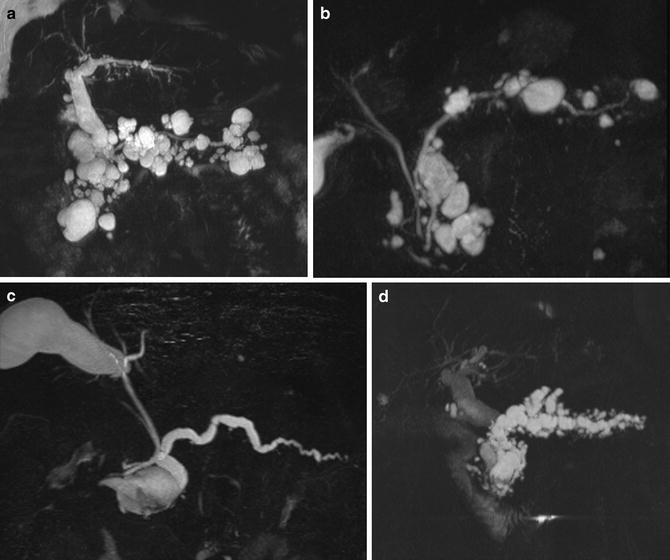

Another diagnostic modality that has become invaluable in the workup and management of pancreatic disease is endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). EUS is highly operator dependent and requires a skilled and experienced gastroenterologist to interpret the study in real time but has the ability to characterize pancreatic masses, cysts, and parenchymal architecture along with fine needle aspiration for cytopathologic evaluation (Fig. 36.3a–d). Utility is greatly increased by on-site determination of sample adequacy and preliminary diagnosis by an expert pathologist that is immediately available. In fact, this modality has replaced percutaneous needle biopsy as the preferred method for obtaining tissue diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy. EUS is a very safe and minimally invasive procedure that can also provide palliation for patients with surgically unresectable disease by performing celiac plexus neurolysis. EUS is highly accurate regarding T and N staging for pancreatic adenocarcinoma, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, and distal common bile duct cholangiocarcinoma [4]. Many surgeons argue that for resectable disease, EUS is unnecessary because tissue diagnosis is not mandatory for a patient with a pancreatic mass who is otherwise a good surgical candidate. The greatest value of EUS is that it permits high resolution imaging with simultaneous sampling. Therefore it is very useful in the evaluation of pancreatic cystic lesions, which are becoming more frequently incidentally found by the increasing use of highly sensitive cross-sectional imaging for other abdominal pathology. Information obtained by EUS can include surrounding inflammatory or fibrotic changes consistent with chronic pancreatitis, communication or involvement of the main pancreatic duct consistent with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN), debris or mural nodules within the cyst wall, or fluid aspiration with tumor marker and enzyme evaluation, presence or absence of mucin, as well as biochemical fluid analysis [5].

Fig. 36.3

(a) Endosonographic ultrasound image of a small side branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. (b) Endosonographic ultrasound image of a serous microcystic neoplasm of the pancreas. (c) Endosonographic ultrasound image of a T1 mass in the head of the pancreas. (d) Endosonographic ultrasound image of a fine needle aspiration biopsy verifying invasive adenocarcinoma

Improved pancreatic imaging has led to lower rates of nontherapeutic laparotomies for pancreatic malignancies and pancreatic resections for benign indications. Additionally, accurate preoperative diagnostic imaging will assist the surgeon in identifying borderline or locally advanced disease prior to surgical exploration. Unresectable vascular involvement should be determined prior to entering the operating room because intraoperative surgical assessment of the extent of disease is difficult to determine even for experienced pancreatic surgeons due to the desmoplastic and inflammatory changes that often accompany benign and malignant pancreatic disease conditions. For the most part, nontherapeutic operations due to unresectable disease at experienced centers are mostly limited to patients with small volume peritoneal or surface liver disease, which is difficult for any imaging modality to find. Diagnostic laparoscopy prior to surgical resection still has a role for patients with malignant pancreatic disease, often most useful for patient presenting with back pain, weight loss, significantly elevated tumor markers, and lesions in the body/tail of the pancreas. Typically, however, the yield of this modality often inversely correlates with the quality of preoperative imaging.

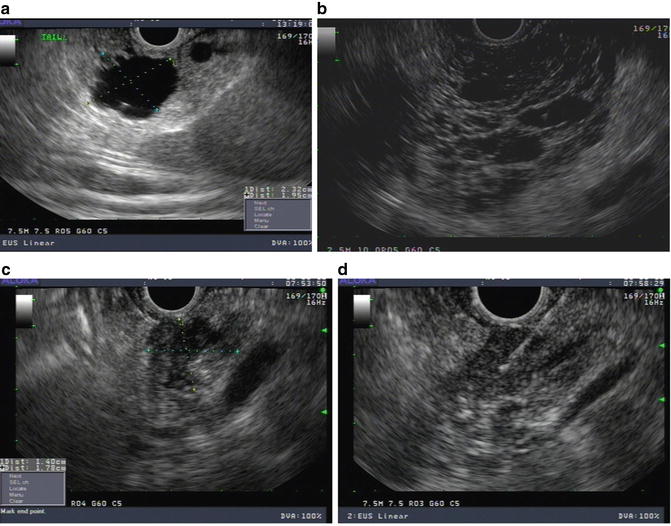

Borderline resectable pancreatic tumors have received increased attention in the past several years. While at most centers patients with resectable disease will proceed directly to surgery and those with locally advanced or metastatic disease will undergo palliative treatments, patients with borderline tumors will be considered candidates for neoadjuvant treatment with chemotherapy, external beam radiation, or proton beam therapy. The clinical advantages of neoadjuvant treatment for these patients will include allowing for a time period of observing tumor biology and response to the treatment given. If very aggressive or metastatic disease is noted during restaging protocols, the patient is likely spared an operation that would have been associated with very little chance of success or benefit. Additionally, preoperative treatment for patients with borderline disease may downsize the tumor, allowing for a less aggressive vascular resection and fewer postoperative complications as well as helping to decrease the risk of an R1 margin positive resection, which has been shown to have a negative impact on long-term survival. Pancreatic surgeons, however, have only recently come to define borderline resectable pancreatic tumors, and this definition varies based on the use of a single institutional classification or a consensus definition proposed through international societies and associations [6]. Regardless of what definition is used, for the most part, patients with borderline resectable pancreatic tumors are preferentially given neoadjuvant preoperative treatments and have a reasonable rate of eventually proceeding to surgery. On the other hand, patients with locally advanced disease, often characterized by circumferential involvement of the superior mesenteric artery or long segment occlusive disease of the portomesenteric venous system with non-reconstructible anatomy, are very rarely if ever downstaged to resectable disease (Fig. 36.4a, b).

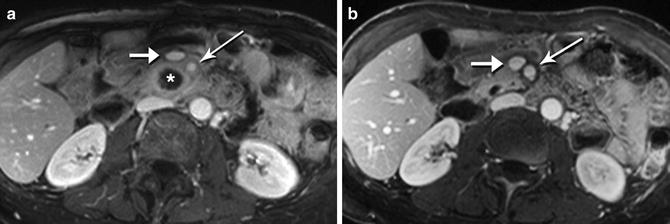

Fig. 36.4

(a) Markedly hypoenhancing tumor (asterisk) in association with complete encasement of the superior mesenteric artery (long arrow) (Short arrow = superior mesenteric vein). (b) After 7 months of neoadjuvant therapy, tumor tissue has receded from the SMA, with apparently clean margins. The patient underwent a complete resection with a margin negative pancreaticoduodenectomy. Tumor pathology showed significant treatment response

Preoperative administration of neoadjuvant treatment for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma is becoming more frequently performed but has yet to significantly improve long-term survival of patients. Selection criteria, treatment protocols, chemotherapy agents, and the use of radiation vary widely between institutions and trials making meaningful analysis difficult [7]. However, it is important to note that patients undergoing treatment prior to pancreatic surgery have not experienced an increased rate of complications or mortality after surgery. Neoadjuvant treatment protocols clearly have the advantage of selection bias by avoiding surgical intervention for those with aggressive disease or those patients with poor performance during treatment administration. Perhaps the greatest value of this treatment, until more effective agents are discovered, is in resource allocation of the surgical procedure to those patients who will benefit the most.

Elderly patients, who often have more medical comorbidities than their younger counterparts, are being more frequently evaluated for surgical treatment of pancreatic pathology. Due to advances in perioperative anesthesia, postoperative care, and the increasing safety of the procedure, these patients are undergoing pancreatic surgery often without a significantly increased complication or mortality rate over younger patients. Studies have demonstrated that elderly patients can safely undergo pancreatic surgery and that age alone is not a contraindication [8]. Pancreatic surgeons continue to push the limits for safe surgery for patients with cardiac, pulmonary, or other medical disease that were once thought to be associated with too much risk for postoperative complications.

Preoperative biliary stenting performed for obstruction within the head of the pancreas had previously been introduced as a method to decrease the risk of complications after PD as a way to improve liver dysfunction. However, multiple studies including a large multicenter randomized trial comparing preoperative biliary drainage versus proceeding directly to surgery indicate that this practice is not necessary and may actually increase the risk of infectious complications for these patients [9]. Generally, preoperative biliary drainage is used only for patients who are not proceeding directly to surgical resection within a reasonable time period and an endoscopic route is greatly preferred over a percutaneous route.

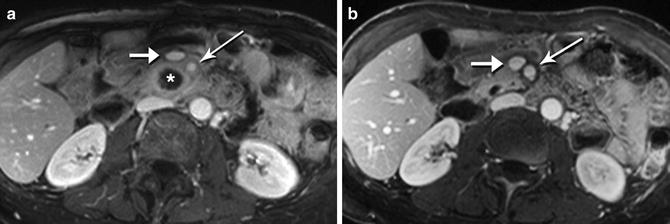

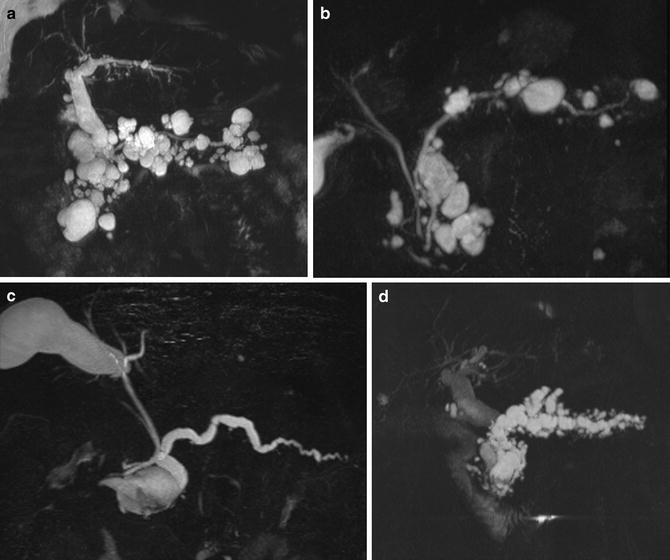

Pancreatic cystic lesions are becoming more frequently identified by the widespread use of cross-sectional imaging and are more frequently being referred for evaluation (Fig. 36.5a–d). Many of these lesions are mucinous cysts with the possibility of harboring preneoplastic or invasive disease. Therefore, multidisciplinary recommendations based on available literature have given treatment algorithms (Modified Sendai Criteria) for the evaluation, surgical treatment, and follow-up for these lesions [10]. In short, surgical resection is recommended for all fit patients with main duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (MD-IPMN) and mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN). Branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (BD-IPMN) with high-risk characteristics including obstructive jaundice, enhancing mural nodules, dysplastic cytology, or main duct involvement should undergo surgical resection. Other worrisome features include size greater than 3 cm, thickened cyst wall, nonenhanced nodule, borderline main duct dilation, focal stricture, cyst growth, and other abdominal symptoms. Surgical treatment is often recommended for these patients, and if not, very aggressive close follow-up is recommended as the risk of malignancy is considerably higher for these patients over those who have none of these worrisome features.

Fig. 36.5

MRCP images of IPMN. Diffuse side branch IPMN with normal main pancreatic duct (a, b) and diffuse mixed side branch and main duct IPMN (c, d)

Intraoperative Advances

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a highly lethal neoplasm, and disease control often fails even after apparent complete surgical resection. For this reason, investigation into more complete surgical clearance of disease has been performed in the past. Radical regional pancreatic resections including total pancreatectomy, extended lymphadenectomy, and extensive vascular resections have fallen out of favor and are not associated with an increase in patient survival. In fact, these extended regional resections are generally associated with greater frequency of postoperative complications with little additional benefit over other techniques. However, concepts proposed by these surgical strategies certainly have merit.

The surgical resection margin for patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma has repeatedly been demonstrated as a major predictor of survival. The prognosis for patients with positive margin is often much poorer, and the average survival has historically not been much higher than for patients undergoing palliative treatment. Therefore, wide en bloc clearance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma encompassing regional vascular or contiguous organs to obtain these margins is favorable for patient survival. It is unknown whether additional re-resection of an initially positive margin has actual benefit towards long-term survival similar to that of an initially margin negative resection (R0). Therefore, as stated above, preoperative imaging is of vital importance to carefully assess the feasibility and plan for an R0 resection. A surgeon should not undertake an operation that is felt to have a low chance for an R0 margin, especially in the era of options that include neoadjuvant therapy.

Accurate margin analysis is considered to be of extreme importance when determining patient prognosis after resection. Microscopic margin positive rates (R1) have been reported at widely variable rates even at high-volume institutions due to variable pathologic processing methods and definitions of what constitutes an R0 versus R1 resection. The resection margins of the retroperitoneally located pancreatic gland are notoriously difficult for pathologists to assess, and the circumferential surfaces may have variable terminology between surgeons and pathologists. Verbeke has done considerable work to describe in detail the accurate and uniform assessment of a pancreaticoduodenal specimen [11]. An optimal situation is present when the surgeon and pathologist remain in clear communication regarding an accurate assessment of each pancreatic margin by frozen section analysis at the time of the operation. Many surgeons will be directly involved in marking different anatomic surfaces and providing the pathologist orientation of the specimen in this process.

For tumors in the head of the pancreas, mesenteric and portal venous resection may be required for complete en bloc tumor clearance. This too has been studied quite extensively and has been clearly shown to be a suitable method to assist in avoiding positive margins of the vascular groove, and retroperitoneum and has not been associated with worsened survival compared to patients who do not need vein resection. Multiple technical options for resection and reconstruction have been reported and include adjunctive intraoperative measures such as superior mesenteric artery occlusion and systemic heparinization [12]. In general, vascular involvement is ideally determined by high-quality preoperative imaging, neoadjuvant treatment is considered, and the surgeon is prepared to perform an en bloc vein resection with the necessary resources to perform suitable reconstruction in the operating room.

Pancreatic resection in combination with arterial resection, as opposed to vein resection, has not been associated with any significant survival benefit and is associated with increased complications. Resection of a long segment common hepatic artery, superior mesenteric artery, or celiac artery has been reported as technically feasible but is rarely if ever associated with any long-term survivors. Resection of the celiac artery with en bloc distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (Appleby procedure) has been described as a surgical option for stage III pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the neck and body of the pancreas that has circumferential celiac artery involvement. Recently, this procedure has been described after neoadjuvant treatment and relies on the pancreaticoduodenal arterial collateral circulation to maintain hepatic and gastric circulation. Carefully selected patients can achieve an estimated median average survival up to 26 months but had a very short disease-free survival of only 21 weeks [13].

Lymph node analysis, like surgical margins, has received additional attention as a predictor of overall survival for patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Nearly all studies show a significantly worsened survival for those with node positive (N1) disease versus those without node involvement (N0). In addition, data supports the notion that for N1 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, the number of lymph nodes involved also seems to affect overall patient survival. The Hopkins group found that an increasing lymph node ratio (LNR) was highly predictive of poorer overall survival [14]. It remains to be seen whether surgical modifications in the operating room to increase the number of lymph nodes examined (thereby lowering the LNR) or increasing the robustness of the pathologic assessment evaluation will result in an increased survival or at least improved prognostic information. Regardless, lymph node harvest is a closely followed surrogate marker for oncologic appropriateness of a pancreatic resection for malignancy.

The magnitude of impact that operative blood loss and packed red blood cell transfusions have has recently come to light with reports indicating that increasing estimated blood loss [15] and the use of transfusions [16] significantly negatively impacts overall survival in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma after surgical resection. This factor may be the single most surgeon-controlled factor that can impact the patient’s long-term outcome and has received attention as a quality control measure for optimal performance of pancreatic resection. Even for those patients without neoplastic disease, the short- and long-term detrimental effects of packed red blood cell transfusions are significant, and efforts should be made to avoid major hemorrhage during any pancreatic operation. Transfusion of packed red blood cells, while not always avoidable during major pancreatic surgery, is thought to have an immunosuppressive effect through a process that is not fully understood at this time.

Emphasis on obtaining a circumferentially negative margin resection for pancreas adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas has led some surgeons to develop the procedure termed radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy (RAMPS). This procedure emphasizes a deeper posterior margin to include an en bloc resection of the anterior renal fascia and, occasionally, the left adrenal gland and Gerota’s fascia along with concomitant DP and splenectomy. Utilization of this particular modification has allowed patients with malignancy of the left-sided pancreas, historically associated with even poorer survival, to obtain impressive estimated median of 26 months and 5-year survival of 35 % [17]. Minimally invasive RAMPS is also feasible and allows for a meticulous dissection performed under magnified vision within noninvolved tissue planes to permit wide dissection around a neoplasm known for its locally invasive nature.

Total pancreatectomy (TP), while not the answer to improved survival for pancreatic adenocarcinoma localized within either the proximal or distal pancreas, has its place for treatment of certain disease states of the pancreas. This operation has recently become more commonly performed for several reasons. It is currently recognized that the malignant degeneration of MD-IPMN leads to adenocarcinoma and requires an aggressive resection of a dilated main duct which frequently involves the entire pancreas gland. Patients requiring complete removal of the pancreas will have instantaneous complete endocrine and exocrine insufficiency resulting from the loss of the entire organ, but the brittle diabetes and malnourishment seen in the past has been greatly improved by modern replacement therapy. Many centers have reported improved outcomes [18] and quality of life after TP for neoplastic disease, and it is no longer a dreaded operation for the patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree