Chapter 6 Outcomes in Pediatric Critical Care Medicine

Implications for Health Services Research and Patient Care

Quality in health care has received increasing attention over the last several decades. This focus has been particularly apparent over the last 10 to 15 years and has captured the attention of clinicians, managers, executives, insurers, and policy makers.1,2 Unfortunately, much of the discourse has been vague, and clinicians, in particular, may not fully understand how quality is defined, what it means to their patients, and how it can be incorporated into their daily practice.

Pediatric critical care medicine (PCCM) has experienced challenges similar to those of other disciplines in attempting to quantify clinical outcomes. As physicians, we are biased in our assessments by our knowledge and experience. Physicians rarely have sufficient objective and quantifiable data to make decisions about outcomes, except perhaps at the extremes of illness severity. Often, there is insufficient time for understanding how clinical decisions are made, how care is delivered, and how to evaluate the achieved outcomes. Without the evaluative step, we fall short in identifying opportunities to improve our care. While physicians certainly do influence the ultimate outcomes of the critically ill child, the system of care includes important contributions by other clinical team members and non-human factors that can also influence quality and outcomes.3

What Is Health Services Research?

Health services research (HSR) is a field of inquiry that is concerned with the creation of new knowledge related to the organization and delivery of health care services and their outcomes.4,5 A number of formal definitions have been provided by leading organizations over the last several decades and demonstrate how the conceptualization of HSR has evolved with time and become more comprehensive (Table 6-1).6–8

Table 6–1 Contemporary Definitions of Health Services Research

| Source | Year | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality | 2002 | Health services research examines how people get access to health care, how much care costs, and what happens to patients as a result of this care. The main goals of health services research are to identify the most effective ways to organize, manage, finance, and deliver high quality care; reduce medical errors; and improve patient safety. |

| Academy for Health Services Research and Health Policy | 2000 | Health services research is the multidisciplinary field of scientific investigation that studies how social factors, financing systems, organizational structures and processes, health technologies, and personal behaviors affect access to health care, the quality and cost of health care, and ultimately our health and well-being. Its research domains are individuals, families, organizations, institutions, communities, and populations. |

| Institute of Medicine | 1995 | Health services research is a multidisciplinary field of inquiry, both basic and applied, that examines the use, costs, quality, accessibility, delivery, organization, financing, and outcomes of health care services to increase knowledge and understanding of the structure, processes, and effects of health services for individuals and populations. |

| Institute of Medicine | 1979 | Health services research is inquiry to produce knowledge about the structure, processes, or effects of personal health services. A study is classified as health services research if it satisfies two criteria: it deals with some features of the structure, processes, or effects of personal health services. At least one of the features is related to a conceptual framework other than that of contemporary applied biomedical science. |

The discipline of HSR has relevance for social science fields like health policy and economics as well as for clinical disciplines like PCCM. This section will focus on how pediatric critical care is organized and how bedside care can be used to explore differences in treatments and outcomes within and across pediatric intensive care units (PICUs), hospitals, regions, and populations, so that new knowledge is generated, shared with colleagues, and applied. The results of HSR can also inform policy decisions that can influence the organization, financing, and structure of health care delivery for critically ill children.4

A System of Care

An organized and methodical system of care is necessary to ensure that critically ill children receive care that is of the highest quality.9 This begins prior to the time when the services are actually needed and relies upon a primary care structure that ensures children can benefit from preventive strategies designed to keep them healthy. There are important strategies that are necessary for assuring childhood health including adequate nutrition, appropriate vaccinations, and easy access to clinicians for acute minor illnesses and injuries, necessary medications, and follow-up care for chronic conditions. Unfortunately, in some settings, the capacity to manage pediatric health prior to acute illness is lacking. The result is that timely delivery of services cannot be ensured and an unnecessary burden is placed upon emergency department (ED) services.10

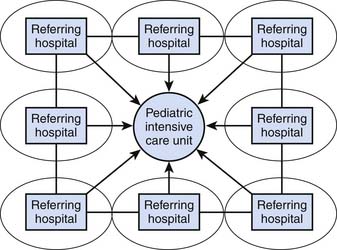

The provision of health care is complex and requires appropriate organization. The study and evaluation of the organization of care, as is accomplished using HSR methods, provides some of the most fertile ground for generating new knowledge and identifying opportunities to improve outcomes for critically ill children.4,5 Some believe that this organization, particularly for high-end pediatric clinical services like pediatric critical care, should be highly regionalized (Figure 6-1). There are a number of good reasons to favor regionalizing care, including the need to reduce unnecessary variation and improve outcomes and resource use, both from a structural (e.g., ICUs, bed numbers) and a human perspective (e.g., manpower issues). However the term ‘regionalization’ does not convey one of the most important aspects of PICU care related to outcomes—integration of care. Regionalizing care will prove to be insufficient for generating good outcomes if care from the child’s immediate environment to the tertiary or quaternary hospital is not integrated, and if there is not shared accountability for outcomes at the population level.

Most states have coordinated systems for supporting the care of the acutely ill or injured patient on a regional basis.11 This is good news, but unless the regional care structures are integrated into a hierarchically arranged system of care based upon increasing patient complexity, outcomes may fall short. In an integrated model, children with acute illness can gain access to the health care system through a number of different access points and be cared for by appropriately trained personnel at each level of care.10 For those children whose condition deteriorates or whose care needs become more complex with time, the system’s integrated components can assure that the child’s and family’s needs are met in a timely and seamless manner by progression through the integrated system with established measures of performance.12 The investigation of how the health care system is organized, how the system’s components operate, how it is funded, and what alternatives may work better are fundamental HSR analyses.

Organizing Health Systems

Systems represent a concept of an “integrated whole” that is dependent upon components and the relationships of those components to one another both inside and outside of the system for the successful delivery of outputs (or outcomes if the system under investigation is health care).13–15 Systems have structure, and this structure provides a framework to organize the components into a hierarchical arrangement, known as microsystems and macrosystems, that helps to provide an understanding of the components’ relationships to one another.13–15

While these terms might imply two different levels of functioning, there are multiple levels of embedded hierarchy that can be described between the microsystem and macrosystem levels.13–15 This approach is useful for describing the complex care required by the critically ill child in the PICU; it provides important opportunities to consider, study, and improve care more broadly for pediatric patient populations, as would be performed in HSR.4–5 To succeed with this approach, the interdependent components of systems need to be considered and criteria-based quality measurement and improvement need to be operationalized within and between the levels of the system’s hierarchy.16 These relationships among and between the system’s components have important implications for addressing both the quality of care and HSR questions.

Microsystems and Macrosystems

Microsystems

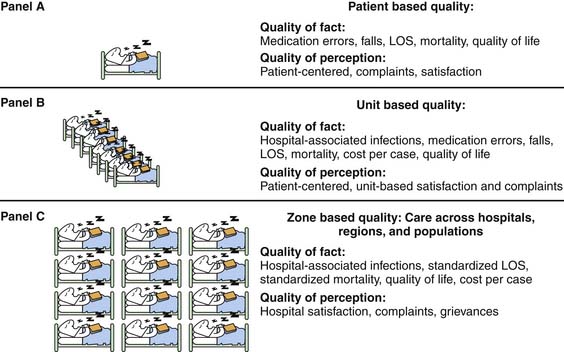

A system’s hierarchy can be collapsed to the frame of reference of a single critically ill child and the respective system components that affect that child (Figures 6-2, A and B). The system components are termed ‘microsystems’ and, when integrated and functioning appropriately, provide for consistent performance.13,15 At the unit level, there is a nursing microsystem; a physician microsystem, often with attendings, residents, and fellows; and microsystems for providing respiratory care, social work, radiology, and laboratory services.13,15 Each of these microsystems operates within a broader framework for providing care across hospital units, or even across hospitals or the population (Figure 6-2, A to C). When components within these systems fail, the child and family may experience adverse events, safety problems, errors, excessively long lengths of stay (LOS), or even unnecessary death, and the family’s perception of the experience is suboptimal.17,18 Normally, these systems function quite well, given their complexity and interdependence; the child achieves a good outcome, and the family is satisfied.

Macrosystems

Variability in performance within microsystems creates problems with performance at the macrosystem level, as care across the different dimensions of quality is aggregated.18 An analytic approach that capitalizes on the contextual elements of individual microsystems while addressing the broader concerns of the macrosystem’s performance is important for understanding and improving the care for the population (Figure 6-2, B and C).13–15 Hierarchical modeling and cluster analysis are some of the available analytic tools to improve our understanding of the interaction of system elements that are parallel or at multiple levels of hierarchy.19 For example, to achieve appropriate estimates of ICU care at the state level (macrosystem), analytic approaches that account for similarities in practice patterns at multiple ICUs within a given hospital (microsystem #1) or within a given city (microsystem #2) because of geographic proximity need to be used. These methods are globally termed hierarchical or multilevel models, because they help to account for biases at multiple levels of the macrosytem.

The six dimensions of quality as described by the Institute of Medicine are operative at both the macrosystem and microsystem levels (Table 6-2).1–2 While the prior section was focused on improving the clinicians’ understanding of how new knowledge can be generated through HSR methods, the intent of the following section is to provide an improved understanding of important patient level outcomes in PCCM for quality improvement. The distinction is a bit artificial in that the study of outcomes in the PICU can also be used to generate new knowledge about delivering care at the bedside.

Table 6–2 The Institute of Medicine’s Aims of Quality

| Quality Aim | Definition |

|---|---|

| Safety | To limit the unintentional harm associated with the delivery of health care |

| Effectiveness | To use evidence-based practices, the best scientific evidence, clinical expertise, and patient values to achieve the best outcomes for patients |

| Efficiency | To provide care that is done well and with limited waste |

| Equity | To provide care that is free from bias related to personal demographics like gender, race, ethnicity, insurance status, or income |

| Timeliness | To provide care without unnecessary wait and to assure that patients have access to the care they need |

| Patient-centeredness | To provide care that reflects a focus on the patient’s needs, including empathy, compassion, and respect |

The Macrosystem: Pediatric Critical Care

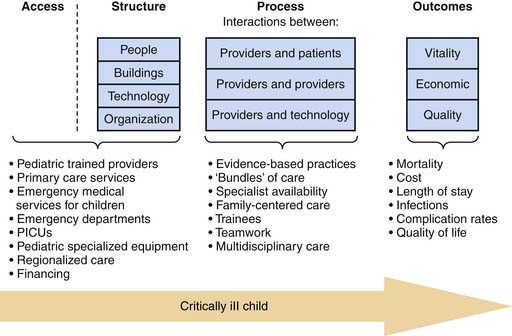

The three major focus areas of interest for considering pediatric critical care at the macrosystem level are access, quality, and cost. These areas also provide an important framework for considering the organization and delivery of care for the critically ill child at the macrosystem level. Figure 6-3 provides a schematic overview of how the critically ill or injured child experiences the health care system. While this figure represents a somewhat linear depiction of these care experiences, the reader is reminded that there is considerable overlap and interaction between the different elements of the system.

Access

Access represents the entry point into the health care system for those seeking care. For children, access represents the availability of appropriate services and financing to ensure that children are able to see providers with the knowledge, skills, and abilities to deliver care appropriately.4 Care needs for children are different from those of adults and require specific considerations for the acutely ill or injured child.

Access to pediatric expertise for anticipatory care and acute care is important. At the policy level, access depends on an adequate number of pediatric providers distributed in a way that assures appropriate primary care. The medical home is one model that attempts to anchor children with primary care providers who act on behalf of the child to organize and coordinate their care.20–22 With this model, age-appropriate anticipatory guidance for health concerns is provided, and vulnerabilities such as underimmunization, obesity, and risk-taking behaviors can be addressed proactively. When a child becomes ill, it is important to have access to providers and services for timely intervention and referral without the need to use other system structures (e.g., EDs). This ensures that care be provided at the most appropriate entry level, thereby saving higher-level resources for those most likely to benefit. This has important implications for the critically ill child.

Acutely ill children can decompensate quickly. Resources to care for these children also must be organized in a way that allows the child to receive lifesaving and resuscitative care immediately (see Figure 6-3). Considerable improvements in prehospital emergency care of children have been undertaken over the last several decades.11 These improvements have been aimed at assuring that community-based prehospital providers have the pediatric training and equipment to deliver appropriate care and safely deliver the child to appropriate ED resources.11

While access points like EDs are readily available in many communities, they may not be staffed or equipped to provide specialty care for acutely ill or injured children.10 Emergency care for children is an example of one ‘specialized care area’ that is notable for considerable variation in ED readiness and provider training for pediatric emergencies.10 Of the more than 30 million pediatric ED encounters annually in the US, only 18% are provided at pediatric EDs.10 Children have important differences in their anatomy, metabolic demands, and disease processes that make the expertise and equipment for their diagnosis and treatment different than those for adults. Unfortunately, only 6% of all EDs nationally had the necessary supplies for pediatric emergencies.10 In addition, there are unique emotional and developmental considerations that need to be accounted for when caring for acutely ill children and their families in the ED, and this expertise may not be present in all EDs. Hence, when confronted with acute, severe, complex, and infrequently encountered pediatric emergencies, long delays may be experienced before definitive critical care services and expertise are available and provided to the child. Given a child’s limited ability to compensate during a physiologic crisis, these delays in care lead can potentially lead to worse outcomes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree