The disease prevalence is 4.3% in Americans under age 40 years; prevalence climbs to 15.5% in those >70 years of age. High-risk individuals include those over 70 years of age, or those over age 50 with risk factors such as diabetes or tobacco use. At least half of these patients also have coronary or cerebrovascu-lar disease.

![]() Acute arterial occlusion secondary to thrombosis or embolism is potentially life-threatening (mortality 25%). In survivors of this condition, limb amputation is necessary in 25%.

Acute arterial occlusion secondary to thrombosis or embolism is potentially life-threatening (mortality 25%). In survivors of this condition, limb amputation is necessary in 25%.

![]() The most frequently involved arteries, in descending order, are the femoropopliteal, tibial, aortoiliac, and brachiocephalic.

The most frequently involved arteries, in descending order, are the femoropopliteal, tibial, aortoiliac, and brachiocephalic.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

![]() In the lower extremities, thrombotic arterial occlusion is more common than embolie arterial occlusion (20% of cases).

In the lower extremities, thrombotic arterial occlusion is more common than embolie arterial occlusion (20% of cases).

![]() In the upper extremities, thrombosis also accounts for the largest proportion of arterial occlusion, but here, one-third of cases are embolic and a quarter are secondary to arteritis.

In the upper extremities, thrombosis also accounts for the largest proportion of arterial occlusion, but here, one-third of cases are embolic and a quarter are secondary to arteritis.

![]() Arteritis can be secondary to Takayasu’s arteritis, Raynaud’s disease, thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease), or collagen vascular disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or polyarteritis nodosa.

Arteritis can be secondary to Takayasu’s arteritis, Raynaud’s disease, thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease), or collagen vascular disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or polyarteritis nodosa.

![]() The embolus usually originates in the heart and atrial fibrillation is responsible for two-thirds of these emboli. A mural thrombus after myocardial infarction is the second most common source of emboli. Noncardiac sources of emboli include tumor, vegetations, prosthetic devices, and thrombi from aneurysms or atheromatous plaques.

The embolus usually originates in the heart and atrial fibrillation is responsible for two-thirds of these emboli. A mural thrombus after myocardial infarction is the second most common source of emboli. Noncardiac sources of emboli include tumor, vegetations, prosthetic devices, and thrombi from aneurysms or atheromatous plaques.

![]() The most common location for an embolus in the leg is the bifurcation of the common femoral artery, followed by the popliteal artery. The brachial artery is the most common site in the upper extremity. Thrombosis can occur at any site of vessel injury.

The most common location for an embolus in the leg is the bifurcation of the common femoral artery, followed by the popliteal artery. The brachial artery is the most common site in the upper extremity. Thrombosis can occur at any site of vessel injury.

CLINICAL FEATURES

![]() Patients with acute arterial limb ischemia typically present with one of the “six P’s”: Pain, Pallor, Polar (coldness), Pulselessness, Paresthesias, and Paralysis.

Patients with acute arterial limb ischemia typically present with one of the “six P’s”: Pain, Pallor, Polar (coldness), Pulselessness, Paresthesias, and Paralysis.

![]() Patients with embolism will have unilateral disease; however, those with thrombosis will have occlusive arterial disease bilaterally.

Patients with embolism will have unilateral disease; however, those with thrombosis will have occlusive arterial disease bilaterally.

![]() Pain and muscle weakness can be the earliest symptoms and pain may increase with elevation of the limb. Commonly seen skin changes include discoloration, mottling, and temperature differences.

Pain and muscle weakness can be the earliest symptoms and pain may increase with elevation of the limb. Commonly seen skin changes include discoloration, mottling, and temperature differences.

![]() Decreased pulse distal to the obstruction is an unreliable finding for early ischemia, especially in patients with peripheral vascular disease and well-developed collateral circulation.

Decreased pulse distal to the obstruction is an unreliable finding for early ischemia, especially in patients with peripheral vascular disease and well-developed collateral circulation.

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL

![]() History of claudication suggests a thrombosis, and many times a source cannot be located (Table 30-1). Other causes of acute arterial occlusion are vascu-litis, Raynaud’s disease, thromboangiitis obliterans, blunt or penetrating trauma, catheter complications, or low-flow shock states such as sepsis. A history of an abruptly ischemic limb in a patient with atrial fibrillation or recent myocardial infarction is strongly suggestive of an embolus; in these cases a source can often be identified (Table 30-2).

History of claudication suggests a thrombosis, and many times a source cannot be located (Table 30-1). Other causes of acute arterial occlusion are vascu-litis, Raynaud’s disease, thromboangiitis obliterans, blunt or penetrating trauma, catheter complications, or low-flow shock states such as sepsis. A history of an abruptly ischemic limb in a patient with atrial fibrillation or recent myocardial infarction is strongly suggestive of an embolus; in these cases a source can often be identified (Table 30-2).

TABLE 30-1 Brief Differential Diagnoses of Intermittent Claudication

TABLE 30-2 Comparison of Disorders Associated with Acute Arterial Occlusion

![]() A hand-held Doppler transducer can document flow (or demonstrate its absence) over the dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial, popliteal, or femoral arteries in the lower extremity, and over the radial, ulnar, and brachial arteries in the upper extremity.

A hand-held Doppler transducer can document flow (or demonstrate its absence) over the dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial, popliteal, or femoral arteries in the lower extremity, and over the radial, ulnar, and brachial arteries in the upper extremity.

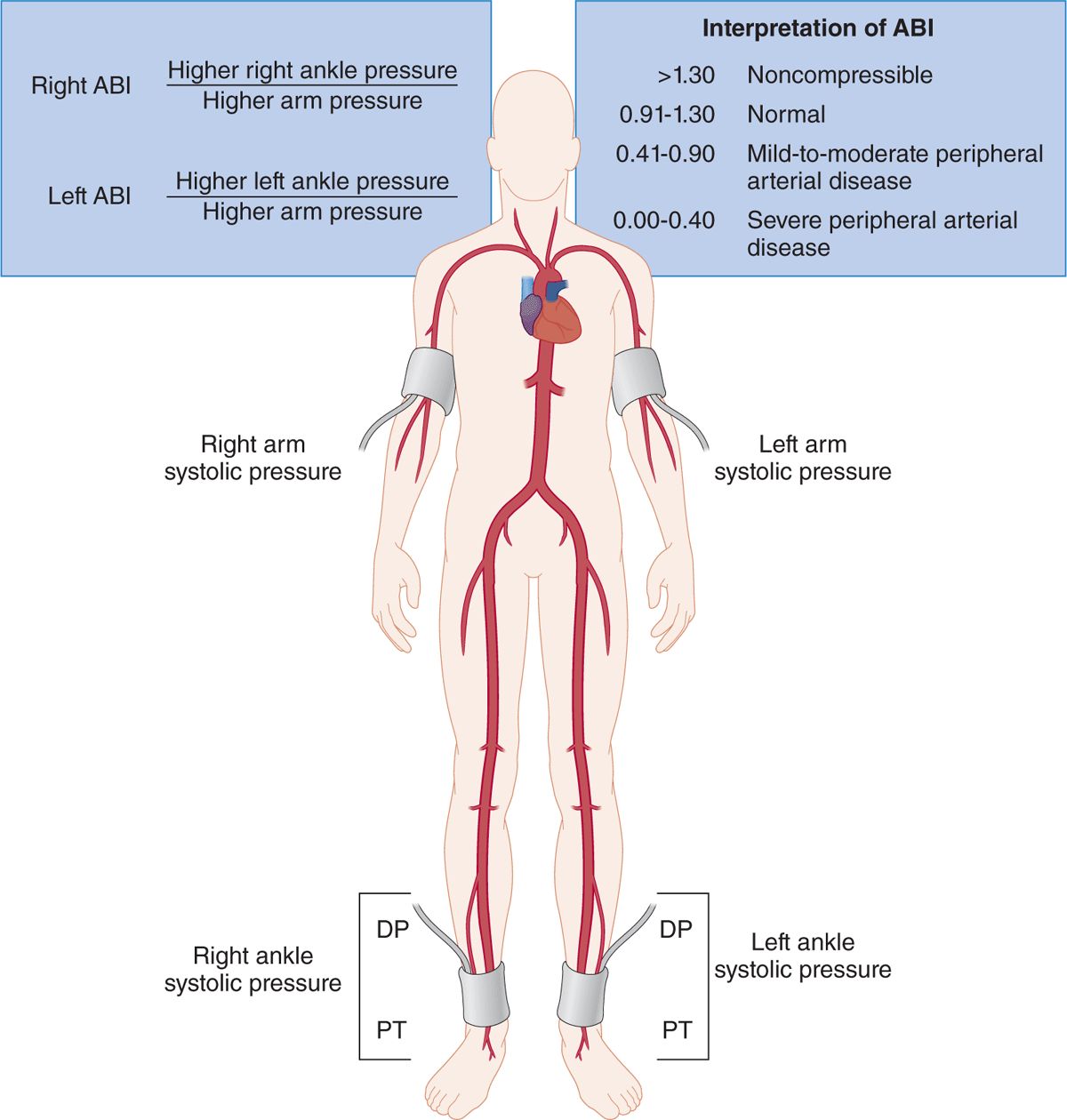

![]() The ankle-brachial index (ABI) is the ratio of systolic blood pressure measured in the lower extremity, to the brachial systolic pressure. With arterial occlusion the ABI is usually markedly diminished (<0.5). A pressure difference of >30 mm Hg between any two adjacent levels can localize the site of obstruction (see Fig. 30-1).

The ankle-brachial index (ABI) is the ratio of systolic blood pressure measured in the lower extremity, to the brachial systolic pressure. With arterial occlusion the ABI is usually markedly diminished (<0.5). A pressure difference of >30 mm Hg between any two adjacent levels can localize the site of obstruction (see Fig. 30-1).

![]() Duplex ultrasonography can detect an obstruction to flow with a sensitivity greater than 85%.

Duplex ultrasonography can detect an obstruction to flow with a sensitivity greater than 85%.

![]() The diagnostic gold standard is the arteriogram, which can define the anatomy of the obstruction and direct treatment.

The diagnostic gold standard is the arteriogram, which can define the anatomy of the obstruction and direct treatment.

FIG. 30-1. Measurement of the ankle-brachial index (ABI). Measure the systolic blood pressure using Doppler US in each arm and in the dorsalis pedis (DP) and posterior tibial (PT) arteries in each ankle. Select the higher of the two arm pressures (right vs left) and the higher of the two pressures in the ankle (DP vs PT). Determine the right and left ABI values by dividing the higher ankle pressure in each leg by the higher arm pressure. The ranges of the ABI and the interpretation are shown in the figure. In the case of a noncompressible calcified vessel, the true pressure at that location cannot be obtained, and alternative tests are required to diagnose peripheral arterial disease. Patients with claudication typically have ABI values ranging from 0.41 to 0.90, and those with critical leg ischemia have values <0.41.

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT CARE AND DISPOSITION

![]() Patients with acute arterial occlusion should be treated with unfractionated heparin, though there is no equivocal evidence demonstrating benefit of this practice (see DVT treatment section for dosing guidelines). Aspirin should also be administered. Use of thrombolytics is controversial, with no clear benefit.

Patients with acute arterial occlusion should be treated with unfractionated heparin, though there is no equivocal evidence demonstrating benefit of this practice (see DVT treatment section for dosing guidelines). Aspirin should also be administered. Use of thrombolytics is controversial, with no clear benefit.

![]() Fluid resuscitation and treatment of heart failure may augment perfusion to the ischemic limb.

Fluid resuscitation and treatment of heart failure may augment perfusion to the ischemic limb.

![]() Definitive treatment should be performed in consultation with a vascular surgeon and an interventional radiologist. Catheter embolectomy using a Fogarty balloon is the preferred approach. Other options include thrombolysis and surgery.

Definitive treatment should be performed in consultation with a vascular surgeon and an interventional radiologist. Catheter embolectomy using a Fogarty balloon is the preferred approach. Other options include thrombolysis and surgery.

![]() All patients with an acute arterial occlusion should be admitted to a telemetry bed or to the ICU, depending on the stability of the patient and the planned course of therapy.

All patients with an acute arterial occlusion should be admitted to a telemetry bed or to the ICU, depending on the stability of the patient and the planned course of therapy.

![]() Reperfusion injury after revascularization of the injury can result in myoglobinemia, renal failure, hyperkalemia, and metabolic acidosis—these complications account for a third of deaths from occlusive arterial disease.

Reperfusion injury after revascularization of the injury can result in myoglobinemia, renal failure, hyperkalemia, and metabolic acidosis—these complications account for a third of deaths from occlusive arterial disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree