An association between benzodiazepine use and oral cleft anomalies was reported in the 1970s, but later case-control and prospective studies failed to demonstrate a relationship between oral cleft anomalies and benzodiazepine use during pregnancy.7–9 Benzodiazepines are now even recommended as a treatment to be considered with refractory hyperemesis gravidarum.10 Opioids, intravenous induction agents, and local anesthetics have a long history of safety when used during pregnancy. A meta-analysis of studies on anesthetic exposure in the workplace concluded that a slight increased risk of miscarriage is the only potential obstetric problem for operating room (OR) personnel.11 The risk of smoking during pregnancy or ionizing radiation risks for pregnant personnel working in radiology departments are much higher than any potential risk for OR staff exposed to trace anesthetics.

Of concern, however, is recent animal work on N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blockers (e.g., ketamine, nitrous oxide) and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptor enhancers (e.g., benzodiazepines, intravenous induction agents, volatile anesthetics).12,13 Currently used anesthetics are thought to act by one of these mechanisms. In animal studies, fetal or newborn exposure to these agents results in widespread apoptotic neurodegeneration and persistent memory/learning impairment. For example, 7-day-old rats (the equivalent of 0 to 6 months of age in humans), which received 6 hours of general anesthesia using midazolam, nitrous oxide, and isoflurane had memory and learning impairments, apoptotic neurodegeneration, and hippocampal synaptic function deficits.14 The relevance to human exposure is unclear, but the equivalent period in humans is from the third trimester to approximately age 3. Are these results in animals attributable to the direct effects of anesthetics, or are they the result of factors we would not see clinically, for example, high anesthetic doses over long periods of time, hypoxia, respiratory acidosis, or starvation? At present, there is not enough information to change our clinical practice, and alleviation of pain and stress during surgery is obviously an essential clinical goal.15,16

CLINICAL PEARLNo anesthetic agents are documented teratogens, including nitrous oxide and the benzodiazepines, but anesthetic neurotoxicity to the developing brain is of concern and the focus of ongoing research.

III.Preoperative plan and counseling

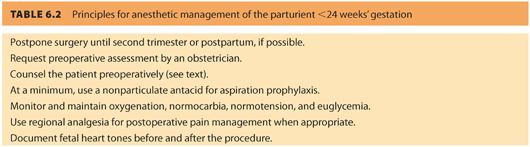

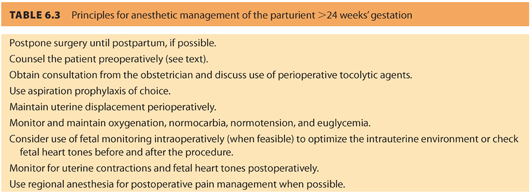

Preoperative assessment should include pregnancy testing if her pregnancy status is uncertain or if the patient requests it, counseling the patient on anesthetic risks (or lack thereof) to the fetus and pregnancy, and educating her about symptoms of preterm labor and the need for uterine displacement at all times after 24 weeks of gestation (see Tables 6.2 and 6.3).

Mandatory pregnancy testing is controversial, raising both medical and ethical issues.17 Any female patient between 12 and 50 years of age should have the date of her last menstrual period documented on the anesthetic record. Pregnancy testing should be offered if more than 3 weeks has elapsed. If surgery can be delayed until the second trimester, the risks of teratogenicity and spontaneous miscarriage are less. In addition, preterm labor is not as common during the second trimester as it is during the third trimester.

CLINICAL PEARLMandatory pregnancy testing is controversial, but testing should be offered and available.

Administration of preoperative medications to allay anxiety or pain is appropriate because elevated maternal catecholamines may decrease uterine blood flow. The decision to use benzodiazepines such as midazolam is up to the judgment of the anesthesiologist and the wishes of the patient. Consider aspiration prophylaxis with some combination of an antacid, metoclopramide, and/or H2-receptor antagonist. Discuss perioperative tocolysis with the patient’s obstetrician. Indomethacin (oral or suppository), oral nifedipine, and intravenous infusion of magnesium sulfate are the most commonly used perioperative tocolytics. Indomethacin has few anesthetic implications, but nifedipine can contribute to hypotension. Magnesium sulphate potentiates nondepolarizing muscle relaxants and attenuates vascular responsiveness, making hypotension more difficult to treat during acute blood loss or volume shifts.

IV.Intraoperative anesthetic management

There is no evidence that any intraoperative anesthetic technique is preferred over another as long as maternal oxygenation and uteroplacental perfusion are maintained. A small study found a higher risk of preterm labor in patients undergoing surgery for an adnexal mass when regional anesthesia was used compared to general anesthesia.18 However, there is no outcome data from larger studies showing that type of surgery, type of anesthetic, trimester in which surgery occurs, length of surgery, estimated surgical blood loss, or length of anesthesia influences pregnancy outcome. Monitoring should include blood pressure, pulse oximetry, end-tidal CO2, and temperature. PCO2 is decreased by approximately 10 mm Hg during pregnancy due to increased minute ventilation, and end-tidal CO2 should be corrected accordingly. Maternal metabolic requirements are increased while FRC is decreased; therefore, arterial desaturation occurs more quickly during apnea or hypoventilation. Blood glucose should be checked during long procedures to ensure normoglycemia.

CLINICAL PEARLNo specific anesthetic technique has been proven to affect outcome. Maternal oxygenation, perfusion, optimal pain control, and early mobilization are key goals.

If it will not interfere with the surgical field, intermittent or continuous fetal monitoring may be performed to ensure that the intrauterine environment is optimized. This may be as simple as checking fetal heart tones (fetal heart rate [FHR]) before and after surgery or as complex as continuously monitoring the FHR throughout surgery. Monitoring should be approached as a medical issue, not a medicolegal one. Justify whether this modality will change your management. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) have issued a joint statement on “Nonobstetric Surgery in Pregnancy” which states in part that “the decision to use fetal monitoring should be individualized, and, if used, should be based on gestational age, type of surgery, and facilities available. Ultimately, each case warrants a team approach (anesthesia, obstetric care providers, surgery, pediatrics, and nursing) for optimal safety of the woman and the fetus.”19 At a minimum, an obstetric consultation should be obtained before surgery to document the preoperative well-being of the fetus and to introduce the woman to their service in case obstetric intervention is needed perioperatively.

CLINICAL PEARLFetal monitoring should be discussed with the obstetric team as part of their preoperative consult.

When continuous monitoring is performed, loss of beat-to-beat variability will occur during general anesthesia or sedation, but fetal bradycardia should not. Decelerations may indicate the need to increase maternal oxygenation, elevate maternal blood pressure, increase uterine displacement, change the site of surgical retraction, or begin tocolysis. Fetal monitoring can help the anesthesiologist assess adequacy of perfusion during induced hypotension, CPB, or procedures involving large fluid shifts. If the mother is awake during regional anesthesia, it can be very reassuring for her to hear fetal heart tones during the procedure. However, intraoperative fetal monitoring may be impractical in urgent situations or during abdominal surgery. Monitoring has not been shown to improve fetal outcome. Personnel with labor and delivery (L&D) expertise may not be readily available, and misinterpretation of the fetal monitor tracing could lead to unnecessary preterm delivery.20 ACOG supports preoperative consultation with an obstetrician before any nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy but states that the need for fetal monitoring should be decided on a case-by-case basis.19

General anesthesia should include full preoxygenation and denitrogenation, rapid sequence induction with cricoid pressure, and avoidance of hypoxia. Keep in mind the pregnant airway is more edematous and vascular, and visualization may be more difficult during laryngoscopy. During the first trimester, high-dose ketamine (>2 mg per kg) may cause uterine hypertonus although usual doses are safe. MAC is decreased 25% to 40% during pregnancy, and inhalational agents should be kept below 2.0 MAC to prevent decreased maternal cardiac output. Nitrous oxide may be used at the anesthesiologist’s discretion. Administering muscle relaxant reversal agents slowly has been recommended to prevent acute increases in acetylcholine that might induce uterine contractions.

Regional anesthetic techniques have the advantage of minimizing drug exposure in early pregnancy. If sedation is avoided, there should be no changes in FHR variability during continuous fetal monitoring. Prevent hypotension after neuraxial techniques with adequate volume replacement and uterine tilt and treat hypotension aggressively with pressors (phenylephrine or ephedrine) if needed. Decrease the neuraxial dose of local anesthetic by approximately one-third from that used in nonpregnant patients. Regional anesthetics provide excellent postoperative pain control, reducing maternal sedation so that (a) the patient can report symptoms of preterm labor, (b) FHR variability is maintained, and (c) early mobilization can occur, reducing the risk of thromboembolic complications.

V.Postoperative care

Postoperative monitoring of FHR and uterine activity should continue. Preterm labor must be treated early and aggressively. Monitoring may require recovery in the L&D unit or provision of L&D nursing expertise in the surgical recovery area or intensive care unit (ICU). Remember that parenteral pain medications will decrease FHR variability; therefore, neuraxial techniques or peripheral nerve blocks should be used when possible. Pregnant patients are at high risk for thromboembolism and should be mobilized as quickly as possible—another reason for aggressive postoperative pain management. If mobilization is not possible, prophylactic anticoagulation should be considered. Maintain maternal oxygenation and left uterine displacement. Neonatology should be notified if the fetus is more than 23 weeks’ gestational age so that the mother can be counseled should preterm labor occur.

CLINICAL PEARLKey postoperative management includes continued monitoring of FHR and uterine activity if the fetus is viable and use of thromboprophylactic measures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree