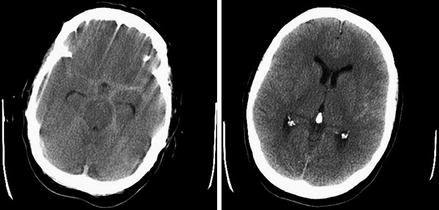

Figure 10.1

Diffuse brain injury Axial CT. Note that even in this severe brain injury, the image on the left is not significantly abnormal. The higher slice shows small petechial hemorrhages in the right frontal lobe which are commonly seen in this type of injury

Key Features of History and Examination

Initial assessment uses the ATLS approach common to all trauma patients. Certain points are particularly important in brain injury.

Mechanism – brain injury causes approximately a quarter of all trauma deaths in Britain, and around half are caused by road accidents. The energy level involved informs as to the likely severity and type of brain injury. A high-energy mechanism is likely to result in more severe primary brain injury, that is, when the brain is injured severely at the moment of impact.

Immediate priority is recognition of the unsafe or occluded airway, recognition of hypoventilation or shock, and associated injuries threatening breathing or circulation as these are potentially treatable factors which will cause exacerbation of the injury, that is, secondary brain injury.

It is essential to accurately assess and record conscious level, using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS – see Table 10.1), and any asymmetry of limb responses and papillary responses as part of the initial assessment and prior to intubation. The conscious level is the most important indicator of the severity of brain injury. Pupillary dilatation may indicate brain herniation with compression of the oculomotor nerve which may occur in severe injuries. A unilateral dilated pupil is a reliable indicator of which side of the brain is affected when it is caused by a focal lesion such as a hematoma.

Table 10.1

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)

Assessment area

Score

Best motor response (M)

Obeys commands

6

Localizes pain

5

Normal flexion (withdrawal)

4

Abnormal flexion (decorticate)

3

Extension (decerebrate)

2

None (flaccid)

1

Verbal response (V)

Orientated

5

Confused conversation

4

Inappropriate single words

3

Incomprehensible sounds

2

None

1

Eye opening (E)

Spontaneous

4

To speech

3

To pain

2

None

1

Each assessment area of the GCS must be recorded individually – motor response, verbal response, and eye opening – rather than the total score. The motor response is the most important guide to the severity of brain injury in most cases, and this essential information must not be embedded within a total score.

History of conscious level on the scene and subsequent deterioration or improvement will indicate information as to the severity and type of injury. A lucid interval is indicative of a less severe primary brain injury which, if followed by deterioration, may become a severe secondary brain injury.

Assessment of the safety of the airway includes the conscious level. An adequate sensorium is required to protect the airway; therefore, an apparently clear airway is not safe if the conscious level is severely reduced and intubation is necessary.

Principles of Acute Management

Brain injury may be classified as primary – that which occurs at the moment of impact – and secondary – that which complicates the initial injury. The main principle of immediate management is to minimize the secondary brain injury. Primary brain injury may be prevented or minimized, for example, by road safety initiatives or vehicle design, but is not treatable.

Good ATLS management is key, as hypoventilation, obstructed breathing, and shock contributes rapidly to secondary brain injury, morbidity, and death.

The conscious level and particularly motor response is the most important indicator of severity, and this may be classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Severe brain injury, when GCS is 8 or less, is associated with inadequate consciousness to protect the airway, so intubation is mandatory for all patients with potentially survivable injuries.

Following initial resuscitation, CT of the head and C-spine should be performed without delay. This will indicate whether there is a focal injury, for example, acute subdural hematoma, extradural hematoma, or intracerebral hematoma (contusion), which might require surgical resection, or a diffuse injury as in this case.

All patients with a significant brain injury should be discussed with the regional neurosurgery team.

Discussion

In the “golden hour” following trauma, it is coordination of good ATLS care which is key. This may be provided by paramedics, A&E staff, and dedicated trauma teams. Systems must be developed to allow the A, B, C, D, and E of trauma care to be delivered in a consistent and coordinated manner. In a modern hospital, this will involve an ATLS-trained team performing simultaneous assessment and management of each of these aspects of care, but if that is not possible, then they must be worked through in that order of priority.

Following resuscitation, CT will allow the neurosurgeon to identify those patients who require urgent surgery for traumatic lesions causing mass effect. Many patients who have severe diffuse brain injury with no specific surgical lesion will also require transfer to the neurosurgical ITU. This will allow invasive monitoring of intracranial pressure by a transducing probe which is placed in the parenchyma or ventricle of the brain, and protocol-guided, coordinated specialist ITU care which aims to minimize secondary brain injury. There is evidence that those patients with severe diffuse injuries who are managed in a dedicated neurosciences center have better eventual outcome than those managed in general ITU. It is as yet unknown which aspects of management produce this difference in outcome [1].

Key Points

1.

Secondary brain injury is potentially treatable, and effective ATLS trauma care is the most important factor during the “golden hour.”

2.

The key aspects of emergency neurological assessment are the GCS with assessment of the pupils and asymmetry of limb responses. This indicates the severity of the injury and may indicate if there is a mass lesion in one side of the brain. It is essential to record the motor, verbal, and eye opening components of the GCS separately rather than just the total score.

3.

When the GCS is 8 or less, immediate intubation is usually required.

4.

CT of the brain and cervical spine should be obtained without delay which will allow the neurosurgeon to identify those patients requiring emergency surgery.

5.

Severely brain-injured patients who do not require emergency surgery also often require transfer to the neurosurgical center for specialist care in ITU.

Clinical Case Scenario 2: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old woman presents to accident and emergency department with a sudden onset of headache. It is the worst headache she has ever experienced and felt as though she had been struck on the back of the head. It occurred while she was in the classroom working as a school teacher. She reports no loss of consciousness but she vomited repeatedly. One hour later, the headache is continuing and she is very nauseated. She now complains of double vision and prefers dim light. Her past medical history includes hypertension and migraine, and she is an ex-smoker. On examination, she has photophobia and neck stiffness but is afebrile. The GCS is 14/15 (obeying commands, orientated, eye opening to speech). Examination of cranial nerves reveals that the right eye is not abducting fully and the diplopia occurs on looking to the right. CT of the brain confirms subarachnoid hemorrhage (Fig. 10.2).