TOPICS

2. Advantages and Disadvantages of Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

3. Indications and Contraindications of Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

4. Preparation for Initiation of Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

5. Neuraxial Labor Analgesic Techniques

6. Initiation of Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

7. Drug Choices for Initiation of Epidural and Spinal Labor Analgesia

8. Maintenance of Labor Analgesia

9. Analgesia and Anesthesia for Operative Vaginal Delivery

10. Management of Breakthrough Pain

11. Adverse Side Effects of Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

12. Complications of Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

13. Adverse Effects of Neuraxial Labor Analgesia on the Progress of Labor

The ideal labor analgesia should provide satisfactory maternal pain relief but not interfere with labor progression or outcome while minimizing adverse side effects to the mother and fetus. Although no single analgesia technique is ideal for all parturients, neuraxial analgesia (epidural, spinal, or combined spinal-epidural) is arguably the analgesic technique closest to the ideal for most women.

PAIN OF LABOR

Pain in the first stage of labor is caused primarily by cervical dilation transmitted via visceral afferent fibers to the T10 to L1 spinal cord segments. As labor progresses and the fetus descends in the birth canal, pain is also caused by vaginal and perineal distension transmitted via somatic afferent fibers traveling in the pudendal nerve to the S2 to S4 spinal cord segments. The pain of cervical dilation tends to be visceral and diffuse in nature. The sacral pain is somatic and localized.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF NEURAXIAL LABOR ANALGESIA

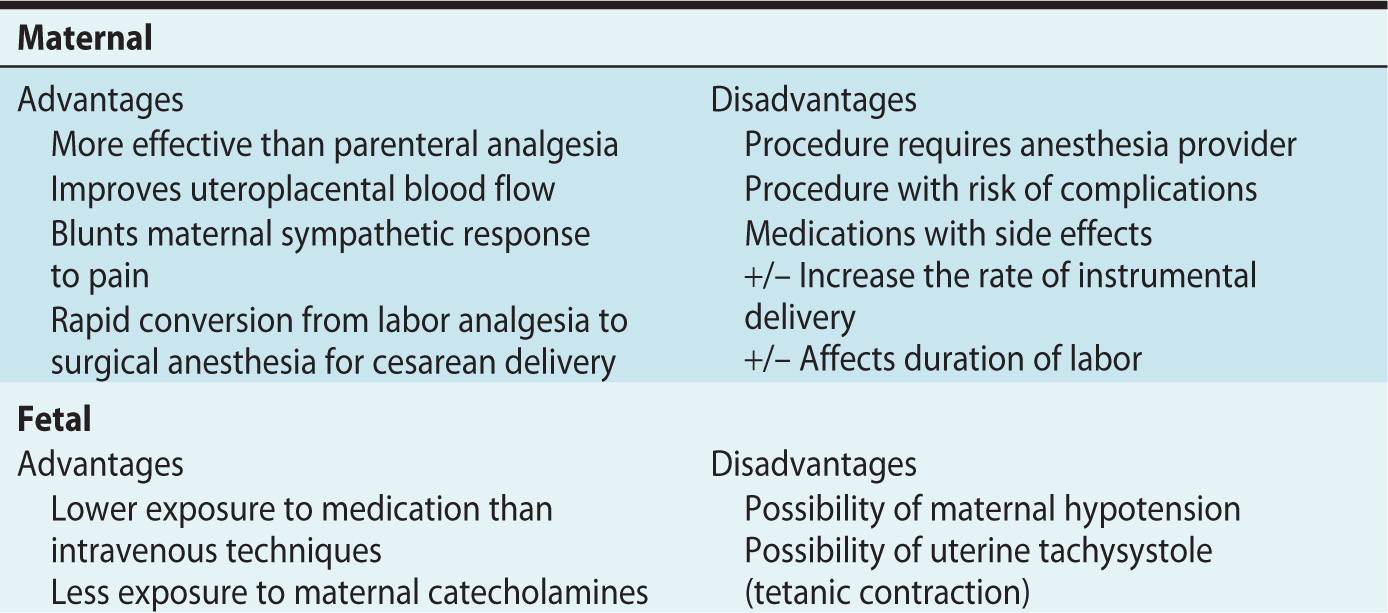

Advantages and disadvantages of neuraxial analgesia are listed in Table 6-1. Neuraxial analgesia is the most effective form of pain relief in labor.1 However, administration of neuraxial analgesia requires the continued presence of a trained anesthesia provider. Although neuraxial labor analgesia is effective and safe in the majority of young healthy women, some women experience complications. Dense neuraxial analgesia may adversely affect the mode of vaginal delivery.

Table 6-1. Advantages and Disadvantages of Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

Alternate options for nonpharmacologic pain relief, particularly in early labor, include sterile water injections, water therapy, continuous labor support, touch and massage, and maternal movement and positioning.2,3 Systemic opioids are the most common form of pharmacologic alternative to neuraxial labor analgesia, but analgesia is incomplete and maternal and fetal respiratory depression limit the dose.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS OF NEURAXIAL LABOR ANALGESIA

Indications for Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

Neuraxial labor analgesia is an elective procedure in the majority of young, healthy parturients. If there is no contraindication, neuraxial analgesia should be provided upon request. Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society of Anesthesiologists have endorsed the following statement: “There is no other circumstance where it is considered acceptable for an individual to experience untreated severe pain, amenable to safe intervention, while under a physician’s care. In the absence of a medical contraindication, maternal request is a sufficient medical indication for pain relief during labor.”4

Neuraxial labor analgesia may be medically indicated in some parturients. Epidural analgesia can be initiated early in labor to avoid the risks of general anesthesia for an emergency cesarean delivery in the setting of anticipated difficult airway, fetal intolerance to labor, or evolving coagulopathy (eg, HELLP [hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count] syndrome). Neuraxial analgesia may also contribute to the safe management of labor and delivery in patients with comorbid conditions, including preeclampsia with severe features (eg, blood pressure control, evolving airway edema), cardiac disease (eg, reduced catecholamines, afterload reduction), and autonomic hyperreflexia.

Contraindications to Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

Absolute contraindications to neuraxial analgesia are listed in Table 6-2. Relative contraindications to neuraxial techniques may include maternal systemic infection, anticoagulation, and some neurologic conditions. With prior administration of appropriate antibiotics to treat maternal systemic infection, transmission of the infection to the spinal or epidural space is unlikely, but neuraxial analgesia could worsen hemodynamic stability in patients with evolving sepsis. Pharmacologic anticoagulation increases the risk of spinal-epidural hematoma. It is important to refer to The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine guidelines for the safe initiation and termination of neuraxial techniques in previously or currently anticoagulated patients.5 Neuraxial anesthesia is likely safe in most patients with underlying neurologic conditions, but a thorough preprocedure neurologic examination and a comprehensive discussion with these patients regarding potential risks associated with neuraxial techniques is imperative.

Table 6-2. Absolute Contraindications to Epidural or Spinal Analgesia

Benefits of neuraxial analgesia administration must be weighed against the risks for any individual patient, and the anesthesiologist must be able to discuss these with the parturient and her obstetric providers and make appropriate recommendations.

PREPARATION FOR INITIATION OF NEURAXIAL LABOR ANALGESIA

The American Society of Anesthesiologists has published “Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia” to guide anesthesiologists in the appropriate management of neuraxial labor analgesia and other aspects of anesthetic management of parturients.6 A checklist for the preparation for neuraxial labor analgesia is outlined in Table 6-3.

Table 6-3. Preparation for Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

Communication with the parturient’s obstetrician or midwife is important to ensure that he or she is aware the parturient is requesting neuraxial analgesia and allows exchange of information regarding the parturient’s obstetric and medical history. A preanesthetic evaluation and focused physical examination is essential, allowing one to anticipate problems that may arise during labor or cesarean delivery, identify contraindications to neuraxial analgesia, and anticipate changes in the parturient’s medical conditions. Blood typing and screening or cross-matching should be considered in women at high risk of postpartum hemorrhage. An anesthetic plan should be based on the anesthetic consultation and written informed consent should be obtained. Women generally want full disclosure, and despite pain and prior use of opioid analgesia are able to give informed consent.7

Resuscitation equipment and medications should be available to manage complications of neuraxial techniques, including hypotension, local anesthetic systemic toxicity, total spinal anesthesia, emergency cesarean delivery, massive postpartum hemorrhage, and respiratory depression (Table 6-4).

Table 6-4. Resuscitation Drugs and Equipment

Adequacy of intravenous access should be assessed before performing a neuraxial technique. In the setting of spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery, administering a crystalloid fluid bolus prior to initiation of anesthesia (preload) has no benefit compared to administering the bolus at the time of initiation of anesthesia (coload). Although the authors routinely administer a 500-mL crystalloid fluid coload to healthy parturients for initiation of low-dose neuraxial labor analgesia, evidence to support this practice is lacking. Phenylephrine is now considered the vasopressor of choice to treat hypotension in the setting of spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery because it results in less neonatal acidosis than ephedrine. Influence of vasopressor choice on neonatal outcome in the setting of hypotension induced by neuraxial labor analgesia has not been studied; however, given the frequency of this side effect following neuraxial techniques in labor, a vasopressor(s) should be readily available.

Maternal blood pressure is measured every 2 to 2.5 minutes during and immediately after the neuraxial procedure for 15 to 20 minutes, and every 30 minutes during maintenance of epidural analgesia. Fetal heart rate should be continuously monitored by a trained professional during (if possible) and following the procedure. Fetal heart rate decelerations may occur secondary to maternal hypotension or uterine tachysystole (see below).

Communication should be ongoing among the anesthesiologists, midwives/obstetricians and nurses throughout labor to ensure accurate and timely exchange of information.

NEURAXIAL LABOR ANALGESIC TECHNIQUES

Continuous lumbar epidural analgesia, the primary technique for labor analgesia, has been used for many years. Anesthetic solution injected into the lumber epidural space spreads cephalad and caudad, providing sensory blockade to afferent pain fibers for both cervical dilation (T10-L1 dermatomes) and vaginal and perineal dilation (S2-S4 dermatomes). Analgesia is initiated with bolus injection of medication through the epidural needle, catheter or both, and maintained with continuous or intermittent administration of medication. An epidural catheter allows rapid conversion from labor analgesia to surgical anesthesia in the event a cesarean delivery is required. Disadvantages of epidural analgesia include a slower onset of analgesia and need for larger doses of medication to initiate analgesia (increasing risk of maternal systemic toxicity and fetal exposure) compared to combined spinal-epidural analgesia.

Combined spinal-epidural analgesia (CSE) is a popular technique because of the faster onset of analgesia, particularly in the sacral area, compared to traditional epidural analgesia.8 Rapid onset of sacral analgesia is necessary in women in the late active phase of the first stage of labor, women in the second stage of labor, and in women whose labors are progressing rapidly. A needle-through-needle technique using a 25-gauge or smaller pencil-point spinal needle is used to initiate analgesia; an epidural catheter is sited for maintenance of analgesia. Additional advantages of combined spinal-epidural analgesia compared to traditional epidural analgesia include the ability to achieve rapid analgesia using a lipid-soluble opioid-only intrathecal injection, particularly in early labor. This results in less maternal hypotension and motor blockade, maintaining the ability to ambulate. The CSE technique requires a dural puncture, although the risk of postdural puncture headache has not been shown to be greater than a traditional epidural technique. The incidence of pruritus is higher with an intrathecal compared to epidural opioid injection.8

Continuous spinal analgesia is typically only used in the setting of unintentional dural puncture with an epidural needle, because only epidural catheters are available in the United States. Because of the large-bore needle required to place the catheter, this technique is associated with a high rate of postdural puncture headache. Continuous spinal analgesia can be used for labor analgesia and converted to an anesthetic for cesarean delivery. The potential for overdose and high-spinal anesthesia or total spinal anesthesia if a spinal catheter is mistaken for an epidural catheter is a real safety concern; all anesthesia providers must be aware of the presence of a spinal catheter on the labor and delivery unit and the catheter and medication pump must be clearly marked as a spinal catheter.

Caudal epidural analgesia is used infrequently because it is technically more difficult to place a caudal than a lumber catheter. Large volumes are required to achieve analgesia to the low thoracic level, thus increasing the risk of maternal local anesthetic systemic toxicity and fetal exposure to medication. This technique may be an option in women with lumbar spine instrumentation.

Single-shot spinal analgesia provides immediate pain relief with a low dose of medication but has a limited duration of action. Therefore, it use is usually limited to imminent vaginal deliveries or in settings in which an epidural catheter cannot be inserted.

INITIATION OF NEURAXIAL LABOR ANALGESIA

An example of the sequence of events for initiating neuraxial labor analgesia is outlined in Table 6-5. The parturient is positioned in either the sitting or lateral position. Sitting is particularly advantageous in obese parturients due to the ease in which midline can be identified. The lateral position may have the advantages of a lower risk of maternal hypotension, allowing easier access to fetal monitoring and improving maternal comfort. The use of preprocedure ultrasonography may help identify midline and interspinous spaces, but whether it improves labor analgesia outcomes is currently not known. Following the neuraxial procedure, the mother should be placed in a lateral position to avoid aortocaval compression and maximize maternal cerebral perfusion if hypotension occurs.

Table 6-5. Initiation of Epidural Labor Analgesia

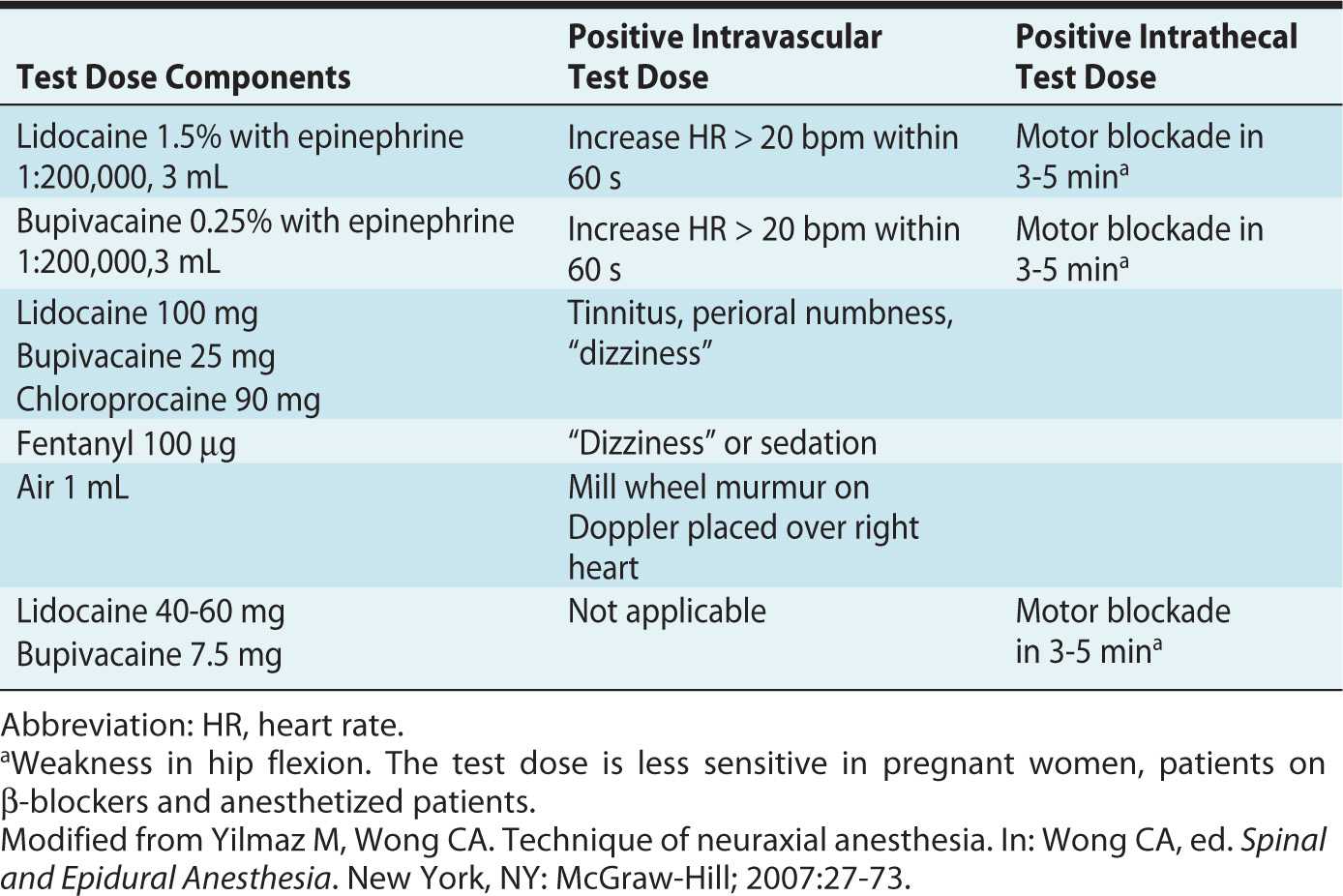

Epidural test doses are given at initiation of epidural analgesia in an attempt to reduce the likelihood that large doses of epidural medication are administered through a malpositioned catheter (intravascular or intrathecal). Some practitioners argue that an epidural test dose may not be necessary if low-dose local anesthetic solutions are injected incrementally through the epidural catheter after negative aspiration; the authors believe that the test dose adds safety, particularly in the event of an emergency cesarean delivery when a rapid injection of a high-concentration local anesthetic solution is required. Aspiration of blood or cerebrospinal fluid is a more reliable sign of intrathecal or intravascular catheter placement with a multiorifice compared to a single-orifice catheter. Common test dose regimens are listed in Table 6-6.

Table 6-6. Epidural Test Dose Regimens

DRUG CHOICES FOR INITIATION OF EPIDURAL AND SPINAL LABOR ANALGESIA

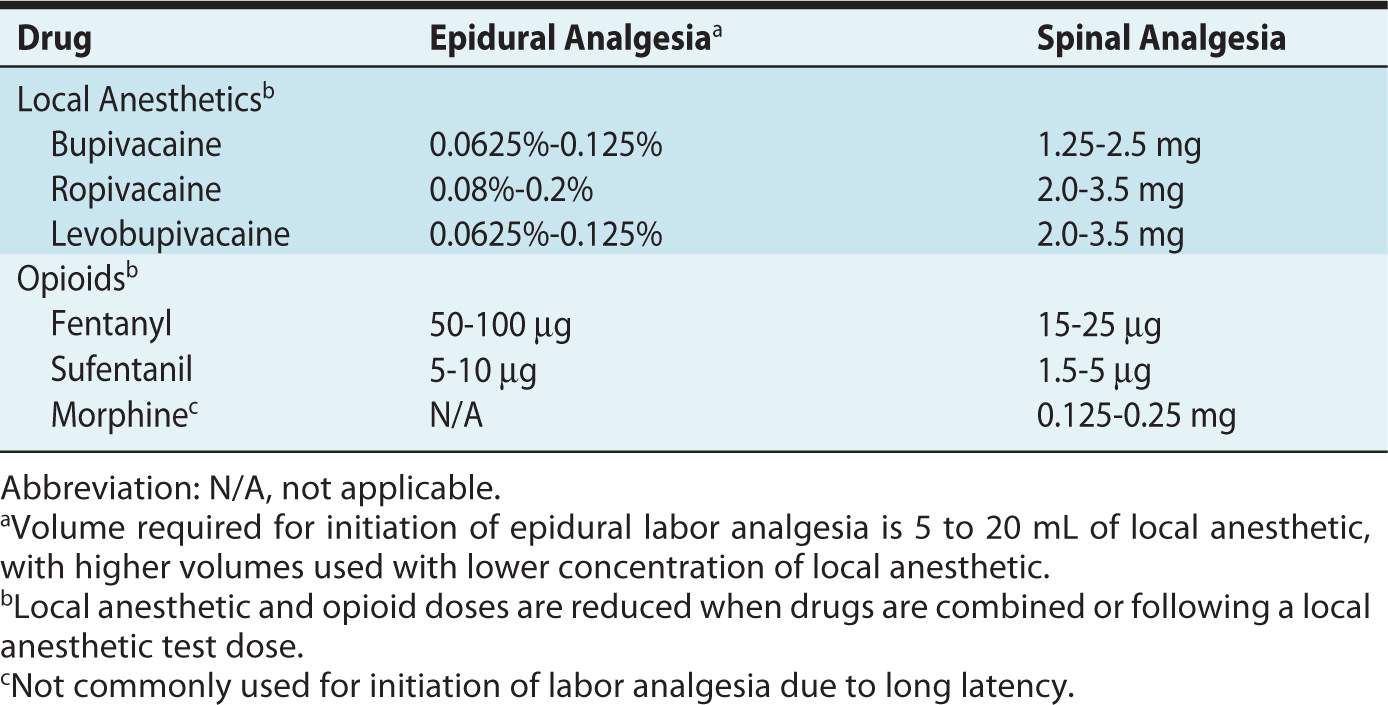

The most common method of achieving effective neuraxial analgesia while minimizing side effects uses low-dose local anesthetic solution in combination with a lipid-soluble opioid. The addition of lipid-soluble opioids to a local anesthetic solution for initiation of epidural or spinal labor analgesia decreases latency, prolongs duration of analgesia, improves the quality of analgesia, and decreases the total local anesthetic requirement.9 The overall opioid requirement is also reduced when used in combination with epidural or intrathecal local anesthetic, effectively reducing side effects of nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and respiratory depression. The typical drugs and dosages used to initiate epidural or spinal labor analgesia are listed in Table 6-7.

Table 6-7. Drugs for Initiation of Epidural and Spinal Labor Analgesia

In general, a higher epidural loading dose is required for initiation of analgesia in active versus latent labor. There is a dose-sparing effect achieved by administering a high-volume/low-concentration local anesthetic solution compared to a low-volume/high-concentration solution.10 The intrathecal dose, as part of a CSE technique for initiation of labor analgesia, provides rapid onset of pain relief with lower doses of drug than traditional epidural analgesia. The spinal injection may provide complete analgesia with opioid alone in early labor. Local anesthetics are injected intrathecally in combination with opioids for active labor because as sole agents, local anesthetics do not provide adequate analgesia unless used in high doses, thus causing the undesirable effect of lower extremity motor blockade.

Local Anesthetics

Bupivacaine, an amide local anesthetic, is commonly used to initiate and maintain labor analgesia. Because it is highly protein-bound in the maternal circulation, uteroplacental transfer of drug is limited. Bupivacaine is most commonly combined with fentanyl or sufentanil for initiation of labor analgesia. Typical onset of epidural analgesia is 8 to 10 minutes, with peak effect at 20 minutes and duration of 90 minutes, depending on the total dose and stage of labor. The typical formulation of plain bupivacaine is hypobaric with respect to cerebrospinal fluid and provides more effective analgesia than hyperbaric bupivacaine when administered in low doses in the intrathecal space.

Ropivacaine, an amide local anesthetic formulated as a single levorotary enantiomer, is similar to bupivacaine in structure and pharmacodynamics. In studies comparing ropivacaine to bupivacaine, ropivacaine was initially believed to cause less motor blockade and less cardiotoxicity than bupivacaine. However, when adjusted for potency (ropivacaine is less potent than bupivacaine), ropivacaine does not have any advantage over bupivacaine for labor epidural analgesia.11 Ropivacaine is not approved for use as an intrathecal injection in the United States.

Levobupivacaine is the purified levorotary enantiomer of racemic bupivacaine and is therefore less cardiotoxic than bupivacaine. The risk of local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) is rare using low-concentration solutions; thus, there do not appear to be any clinical advantages to using it compare to bupivacaine for labor analgesia. It is not available in the United States.

Lidocaine, an amide local anesthetic, is typically not used for initiation or maintenance of labor analgesia because of the short duration of action and higher umbilical vein to maternal vein drug concentration ratio than bupivacaine.

2-Chloroprocaine is an ester local anesthetic with limited utility for labor analgesia due to its short duration of action. Epidural administration of 2-chloroprocaine has a rapid onset (5-10 minutes) of analgesia that lasts 40 minutes with a low risk of systemic toxicity, making it a useful medication for instrumental vaginal or emergency cesarean delivery.

Opioids

Fentanyl and sufentanil, lipid-soluble opioids, are most commonly used for initiation of labor analgesia. High lipid solubility facilitates penetration through the dura (epidural injection) and entry into the spinal cord (intrathecal or epidural injection), resulting in faster onset of analgesia, shorter duration of action, and higher systemic absorption than with water-soluble opioids. Fentanyl and sufentanil both provide complete pain relief in early labor when used as sole agents for intrathecal injection. The duration of analgesia with intrathecal fentanyl alone varies from 80 to 120 minutes and has an analgesic plateau at 25 μg and worsening side effects (eg, pruritus) with increasing doses.12 Sufentanil has greater lipid solubility than fentanyl, resulting in greater spinal cord penetration and potentially faster and better analgesia. Its higher lipid solubility results in higher volumes of distribution and lower maternal plasma concentrations with resultant lower fetal umbilical vein and plasma levels when given as an epidural injection compared to fentanyl. The actual clinical differences between the two drugs are small. Intrathecal sufentanil has a longer duration of action than fentanyl but similar side-effect profile.13 Given that epidural maintenance analgesia is routinely initiated soon after the spinal dose, the longer duration of action of sufentanil may not be clinically relevant. In the United States, sufentanil is used less often than fentanyl because historically, it was more expensive than fentanyl. In addition, it is formulated commercially in a high concentration (50 μg/mL); thus is must be diluted before use, making it less practical and more prone to drug error.

Morphine, a water-soluble opioid, is impractical for routine use in labor analgesia due to its long latency and prolonged effects after delivery. Low doses of intrathecal morphine (0.1-0.25 mg), when combined with bupivacaine and lipid-soluble opioid for initiation of analgesia, make an acceptable alternative for active labor when epidural maintenance medications or resources are not available. Higher doses of intrathecal morphine (0.5-2 mg) are not effective for the second stage of labor and have unacceptably high incidence of side effects, including somnolence, nausea and vomiting, pruritus, and respiratory depression.

Diamorphine (heroin) is available in the United Kingdom and is used in combination with low-dose local anesthetics for labor analgesia, but no studies have compared it directly to fentanyl or sufentanil.

Meperidine is an opioid with local anesthetic properties, but there is no evidence that it is superior to low-dose local anesthetic with lipid-soluble opioid. Intrathecal meperidine (10 mg) can be used as a sole agent for spinal labor analgesia, but it is associated with more nausea and vomiting and is best reserved for patients who have a contraindication to local anesthetic-opioid labor analgesia.

Alfentanil is a lipid-soluble opioid whose analgesic properties have not been directly compared with fentanyl and sufentanil for labor analgesia, but it would presumably be inferior given its lower lipid solubility. Hydromorphone is not well studied for labor analgesia, but its latency and duration of action of lies between fentanyl and morphine. Butorphanol has strong κ-receptor activity, and studies utilizing this drug in labor demonstrated side effects such as transient sinusoidal fetal heart rate pattern and maternal somnolence or dysphoria.

Adjuvants to Local Anesthetics and Opioids for Labor Analgesia

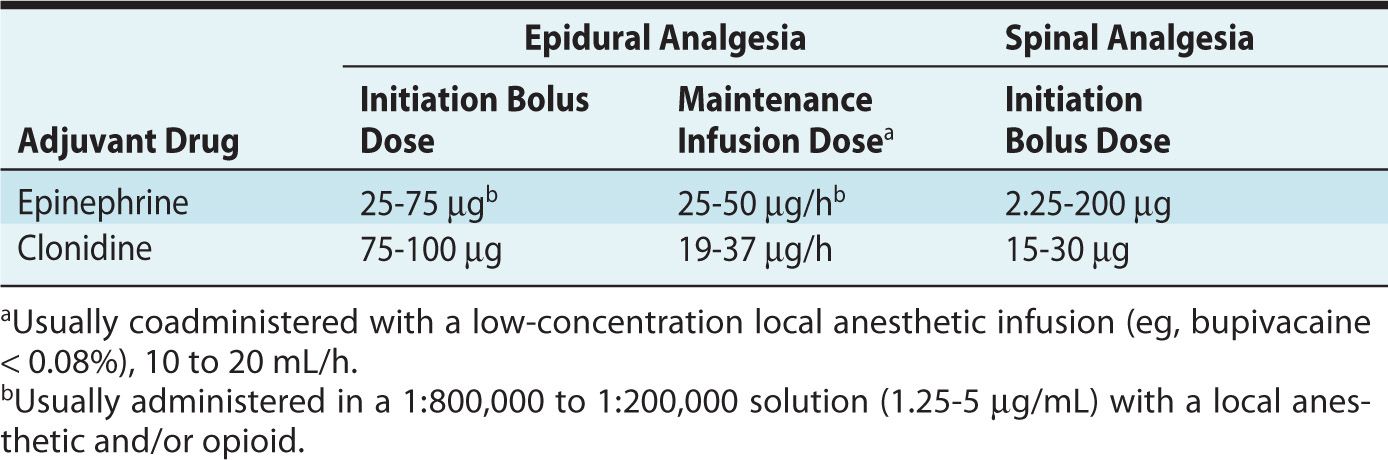

Other medications have been used for their synergistic effects with local anesthetics and opioids to prolong duration of action, improve analgesia and reduce required anesthetic doses with the intent of reducing side effects (Table 6-8). Although these drugs may be used as alternatives or adjuvants, they should not be used routinely due to their high incidence of side effects and little to no advantage compared to local anesthetic-opioid analgesia alone.

Table 6-8. Adjuvants to Neuraxial Labor Analgesia

Clonidine, an α2-adrenergic receptor binder, inhibits neurotransmitter release in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Clonidine, when administered in the epidural or intrathecal space, improves quality and duration of labor analgesia. Although it provides adequate analgesia with no motor blockade, the high incidence of maternal hypotension, sedation and fetal heart rate abnormalities limits its use. The US Food and Drug Administration specifically warns against its use in obstetric patients because of the risk of hypotension.

Epinephrine acts as an analgesic adjuvant by binding directly to α-adrenergic receptors (inhibiting neurotransmitter release in the spinal cord) and causing vasoconstriction (preventing systemic absorption of drugs in the neuraxial space). It prolongs the effects of local anesthetic-opioid analgesia, allowing a decrease in concentration of local anesthetic; however, it increases the incidence of motor blockade and does not improve the quality of analgesia.

MAINTENANCE OF LABOR ANALGESIA

Analgesia must be maintained for at least several hours following initiation of neuraxial analgesia in most parturients. Maintenance of analgesia is accomplished by administering medication through an epidural catheter for the duration of labor. A long-acting, low-dose amide local anesthetic combined with a lipid-soluble opioid is the most common medication solution used for maintenance of labor analgesia.

Patients should be monitored by the anesthesia provider during maintenance of epidural analgesia. Assessment and documentation of the quality of analgesia, sensory and motor blockade, and maternal hemodynamics should be made intermittently throughout labor.

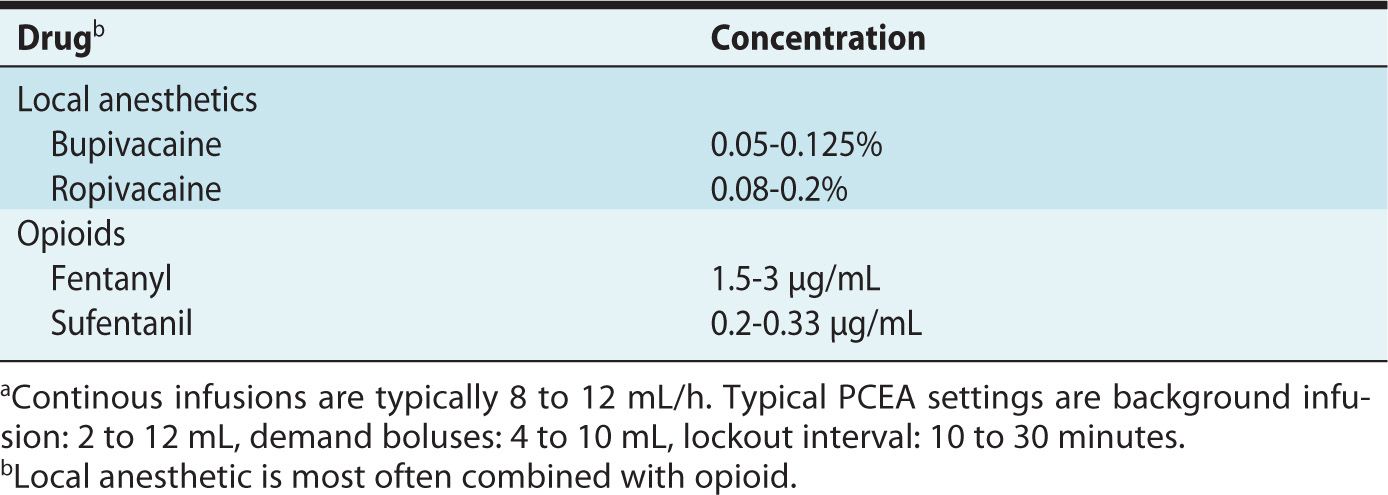

Drugs for Maintenance of Epidural Analgesia

Typical drugs and drug concentrations for maintenance of epidural analgesia are listed in Table 6-9. Bupivacaine and ropivacaine have both been used for maintenance analgesia with no clear advantage of one over the other.11 Although the risk of breakthrough pain (thus requiring more interventions to treat inadequate analgesia) is higher using low-concentration compared to high-concentration local anesthetic solutions, high-concentration solutions are associated with more hypotension and motor blockade. Some studies have found that the incidence of instrumental vaginal delivery is lower using low-dose compared to high-dose local anesthetic solutions for maintenance of epidural analgesia.14 Lidocaine and 2-chloroprocaine are not used for maintenance solutions because of their short duration of action. Epinephrine is sometimes added to the local anesthetic–opioid solution allowing further decrease in concentration of local anesthetic; however, there appears to be no clinical benefit because epinephrine potentiates both the sensory and motor blockade.

Table 6-9. Anesthetic Solutions for Epidural Maintenance Infusions Utilizing Continuous Infusion or Patient-Controlled Epidural Analgesia (PCEA)a

Maintenance Techniques

Historically, manual intermittent boluses of medication were administered by the anesthesia provider for maintenance of epidural analgesia. Although this mode of administration was effective, it was not ideal given the inevitable regression of analgesia, which triggered requests for additional medication and depended on the ready availability of the nursing staff and anesthesia provider to avoid “windows” of pain. Continuous infusions, delivered via a mechanical pump, were found to have a safety profile similar to intermittent manual boluses with more constant analgesia, greater maternal satisfaction, and less need for anesthesia provider intervention. However, infusions compared to boluses of the same local anesthetic concentration results in use of greater volume of local anesthetic solution and greater degree of motor block.15

In modern practice, intermittent boluses with or without a background infusion are given using a patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) technique for maintenance of epidural analgesia. The most effective method of administering epidural medication with PCEA appears to be high-volume, low-concentration local anesthetic with lipid-soluble opioid. Optimal PCEA settings probably depend on the drug concentrations and may be patient-dependent. Although data are inconsistent, a background infusion likely results in more constant analgesia and reduces anesthesia provider interventions compared with no continuous infusion, and it may allow the patient to get more rest.16 An hourly background infusion rate of one-third to one-half the total hourly anesthetic dose has been suggested.16 Higher volume patient-administered boluses (> 5 mL) appear to be more effective than smaller boluses. Higher bolus volumes are used with longer time intervals and the PCEA pumps should be programmed with maximum limits to prevent overdose. Pumps capable of administering automated (programmed) intermittent boluses have been recently introduced and may facilitate bolus administration while allowing the patient to rest.

PCEA pumps should be distinct from the intravenous pumps to minimize accidental adjustments of epidural medication or administration of incorrect medications into the epidural catheter by other hospital providers. Hospital policy should clearly state who can administer or adjust epidural infusion pumps, but only trained anesthesia providers should order adjustment of epidural infusion rates, volume or medication content. Ideally, pharmacists should prepare epidural solutions to ensure sterility.

Maintenance of Spinal Analgesia

Continuous spinal analgesia for maintenance of labor analgesia is indicated in cases of unintentional dural puncture during the initial attempted placement of an epidural catheter. It is also used more rarely for specific indications (eg, morbid obesity, abnormal spine pathology).

The same medications and drug concentrations used for maintenance of epidural analgesia are used for spinal analgesia but at lower infusion rates, typically 2 mL/h. The infusion pump can be set with PCEA bolus administration (1-3 mL) to minimize disconnections of the catheter-infusion tubing and risk of infection or iatrogenic overdose. Our practice is not to give the PCEA button to the patient but rather administer these PCEA boluses via the anesthesia provider, thus encouraging frequent evaluation of the patient with a spinal catheter to assess pain, blood pressure, and sensory and motor blockade.

ANALGESIA AND ANESTHESIA FOR OPERATIVE VAGINAL DELIVERY

In the second stage of labor, pain is caused by vaginal and perineal distension via somatic nerve fibers in the S2 to S4 dermatomes. These are large nerves that may need more local anesthetic to provide adequate sacral analgesia. Some patients require higher concentration and volumes of local anesthetic than can be self-administered via the PCEA for second stage labor analgesia. Unfortunately, this additional injection of medication prior to delivery may cause motor blockade, high sensory block, and minimal sensation of perineal pressure to assist with maternal explosive efforts.

Supplemental analgesia is frequently necessary for women undergoing an assisted vaginal delivery, episiotomy, or repair of episiotomy or complex vaginal laceration. Table 6-10 describes techniques to provide analgesia/anesthesia for these circumstances.

Table 6-10. Anesthesia for Vaginal Delivery