The spectrum of treatment for back and neck pain ranges from the simple application of heat and administration of analgesics at one extreme to open surgery at the other. Multimodal spinal therapy is in the center of this range. It deals primarily with nerve root compression, treating it with a combination of local injections, physical therapy, pain treatment, and behavioral training. The severity of the presenting symptoms determines whether the multimodal program is conducted on an outpatient basis in a day clinic or in an in-patient setting. A multimodal intensive program should be followed when there is no compelling reason for immediate surgery. This program aims to improve symptoms quickly and permanently, preventing chronification and the need for possible surgery later on as a result of ineffective conservative treatment.

Outpatient Minimally Invasive Spinal Therapy

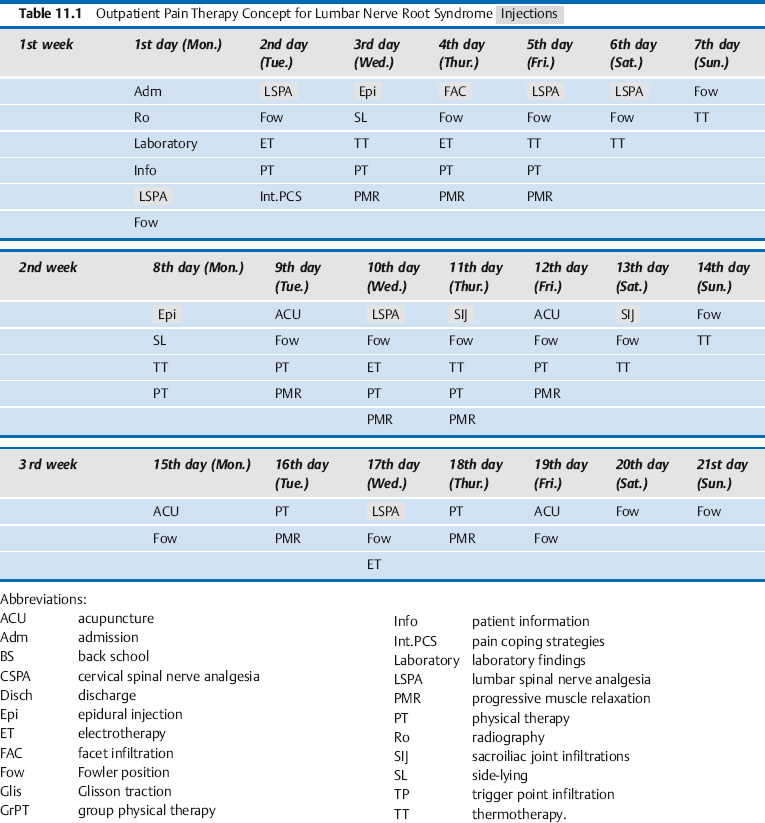

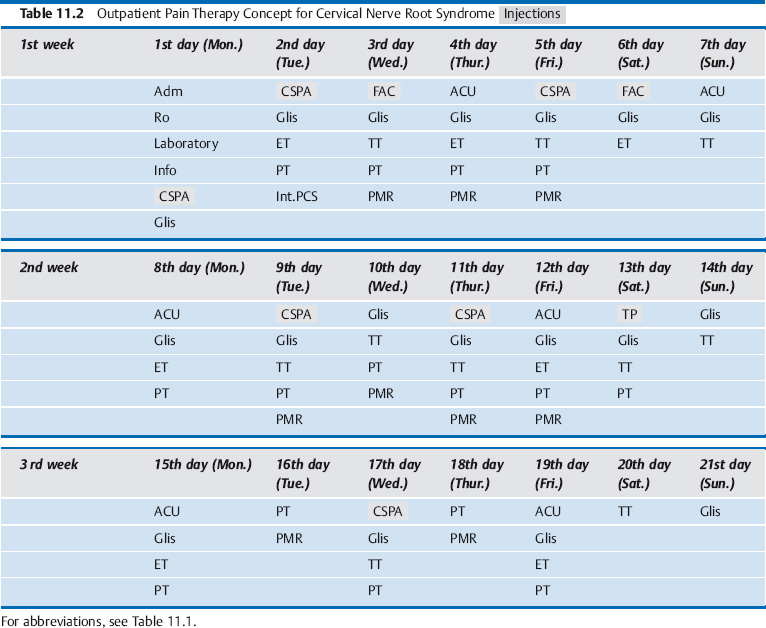

Multimodal spinal therapy, including spinal injections, can in principle be carried out on an outpatient or day hospital basis. Apart from the few interventions that require 24-hour monitoring, such as cervical epidural injections, all the special interventions conducted by physicians can be administered in an outpatient setting. Table 11.5 on page 213 shows the limiting factors for outpatient treatment, which are also the indications for in-patient treatment.

Patients who are admitted to hospital usually present with severe pain, a considerable maladaptive posture, and paralyses that are in the gray area of becoming indications for surgical intervention. They usually arrive at the hospital by ambulance as they are otherwise unable to travel. In-patient observation is also necessary in cases where large prolapses are present, as there is a risk of further paralysis. The indication for the outpatient treatment of a nerve root compression syndrome is therefore “diagnosis by exclusion.”

The first day of outpatient treatment consists of the usual detailed examinations and determining the diagnosis. Once the further diagnostics with radiography and, in some cases, laboratory findings are completed and the patient has received a sufficient amount of information, adequate pain therapy should be administered on the first day in the form of spinal nerve analgesia or epidural injection. In acute cases with severe pain, the cervical or lumbar spinal nerve analgesia is conducted daily over the following days. This is followed in each case by physical therapy, thermotherapy, Glisson traction, Fowler position or side-lying for the lumbar spine, and electrotherapy.

Cervicobrachial syndromes and lumboischialgia have a strong tendency to become chronic. For this reason, pain coping strategies are introduced right from the start. Progressive muscle relaxation follows during the consecutive sessions. The invasive interventions are reduced, with intervals of 2–3 days depending on how the symptoms develop.

Epidural perineural injections and other types of epidural injection therapy are administered a maximum of three times over the entire treatment cycle, with a break of several days between injections. Depending on which is the most prominent primary and secondary pain as time goes on, trigger point and facet infiltration, sacroiliac joint infiltrations, acupuncture, or other interventions drawn from the wide spectrum of treatment possibilities can be administered. In some cases, concomitant therapy with medication is necessary right from the start (see Chapter4, “Multimodal Medication Concomitant Therapy”; Tables 11.1, 11.2).

The patient should also see the physician again some time after the third week, e. g., after a further 3–6 weeks, depending on the amount of irritation in the cervical or lumbar nerve root. The physician uses this opportunity to assess the patient’s orthopedic and neurological status and check the diagnosis. When necessary, local infiltrations are conducted to desensitize the nerve root at this point in time and later at increasingly longer intervals.

The remaining components of the multimodal program are carried out by patients themselves. This applies especially to exercises commencing in the pain-relieving position, and sports that are gentle on the spine.

In-patient Minimally Invasive Spinal Therapy

Intensive IMIST should be conducted over a period of 5–10 days before operating on spinal symptoms that are extremely resistant to treatment. This does not apply if a serious acute paralysis requires immediate surgery. Most cases involve a nerve root compression syndrome arising from an intervertebral disk prolapse, spinal canal stenosis, or postsurgical scarring. In terms of invasiveness, IMIST is intermediate between outpatient specialist orthopedic treatment and open surgery (Theodoridis and Krämer 2003) (Table 11.3). In most cases symptoms improve in the long term, so that open surgery need no longer be considered as a treatment option. The improvement of symptoms is achieved by giving daily injections of analgesics to the spinal nerve and epidural perineural infiltrations, and at the same time implementing a special physical therapy program that continues after the patient is discharged.

The IMIST concept is multimodal, containing medical, physical therapy, and psychotherapy components. The concept has proved itself over the last 20 years with more than 15 000 patients at the Orthopedic University Clinic at St. Josef-Hospital Bochum in Germany. It is continually being improved on the basis of experience and scientific studies. The essential components of the multi-modal program— spinal injections, movement therapy, and behavioral training (back school)—are evidence based and specifically recommended by the Drug Commission of the German Medical Association (Table 11.4).

| Outpatient | In-patient | In-patient |

| General practitioner | IMIST | Open surgery |

| Specialist physician |

| Studies | Evidence | |

|---|---|---|

| Epidural injection | 9 | ↑ ↑ |

| LSPA | 2 | ↑ |

| Intradiscal laser | 2 | ↓ |

| Percutaneous nucleotomy | 2 | ↓ |

| Chemonucleolysis | 4 | ↑ |

| Physical therapy | <6 | ↑ |

| Back school | 18 | ↑ |

| NSAIDs | 25 | ↑ ↑ |

| Myotonolytic agents | 15 | ↑ |

Medical Interventions

The medical interventions are supervised by specially trained orthopedists and pain therapists. Following the minimally invasive interventions (injections), the patient is placed in a special pain-relieving position or in Glisson traction. This is individually adjusted and checked by the physician. Further daily medical interventions e. g., peripheral infiltrations, manual therapy, and acupuncture, are performed at other times and depend on the findings.

The patient’s self-assessment of pain and the clinical neurological findings are assessed regularly, and pain medication is adjusted individually during the in-patient stay. In special cases, changes in medication are decided upon in an interdisciplinary pain conference involving medical pain specialists, psychotherapists, and internal medicine physicians. The pain medication is also assessed after discharge, in consultation with the patient’s general practitioner.

Physical Therapy

The complementary physical therapy consists of

- exercise and muscle strength training

- back school

- thermotherapy

- electrotherapy.

The physical therapy interventions are integrated into the daily routine.

In addition, an individualized sport and movement program is introduced, based on the pain-free range (MIPFR) concept. This continues after the patient has been discharged.

Psychotherapy

These sessions, run by psychologists, take place mainly during the late afternoon. They include training in how to cope with pain and exercises that target muscle relaxation, e. g., Jacobson’s muscle relaxation.

The psychologists also introduce the patients to self-help programs, to provide them with a way of coping with their remaining symptoms after they have been discharged.

Special Interventions

Some special diagnostic and therapeutic interventions are also used in special cases alongside the standard IMIST program. These include:

- spinal infiltrations under image guidance (CT or MRI)

- discography and intradiscal therapy

- interlaminar, transforaminal, or sacral epidural endoscopic therapy

- autologous epidural perineural infiltration with interleukin receptor antagonist protein (IRAP) using the patient’s own blood (see Chapter 4, “Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist Protein”)

- interlaminar or epidural catheterization

- plaster cast test to decide whether fusion is appropriate

- radiculography

- individual physical therapy

- instructions in the use of muscle electrostimulation units

- individual psychotherapy.

Other disorders such as labile hypertension, diabetes, gastrointestinal symptoms, and neurological diseases are treated by consulting physicians from other medical specialisms.

Indications for In-patient Minimally Invasive Spinal Therapy

The main indications for IMIST are serious cervical and lumbar nerve root compression syndromes that cannot be adequately treated in an outpatient setting. They are seen especially as a result of intervertebral disk prolapses, spinal canal stenoses, and postdiscotomy syndromes. Often a combination of these causes is present. Further indications are spondylolisthesis (isthmic or degenerative), osteoporotic fractures, and synovial cysts (Table 11.5).

The criterion for in-patient treatment of spinal disorders is the level of severity, i. e., severe pain and neurological deficits. However, outpatient treatment from a specialist physician should always precede a hospital stay, in order to demonstrate that it is impossible to treat the patient’s symptoms successfully in this way. Outpatient treatment is not useful when pain is regularly graded above 5 on the numeric rating scale (NRS, 0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain imaginable) and when the pain continually increases under loading, e. g., when the patient gets in and out of a car. The spinal nerve root irritation that is reduced by the pain therapy is reactivated when the patient travels home, and this prolongs the healing process.

Neurological findings that are serious enough for surgery to be considered are usually associated with severe pain and must be treated in an in-patient setting (Table 11.6) right away. Surgical intervention is required in the presence of cauda symptoms or the acute loss of important functional muscles. The imaging results (radiography, CT, or MRI) should correlate with the clinical symptoms.

Finally, patients must be willing to be treated on an in-patient basis with daily spinal infiltrations (Table 11.7). Conservative IMIST in an acute hospital is not indicated when the dailyspinal infiltrations cannot be carriedoutfor any one of the reasons mentioned in this table.

Diagnostics Required before Commencing Minimally Invasive Spinal Therapy

The diagnosis must be confirmed before commencing minimally invasive spinal therapy. Warning symptoms should be investigated by taking a detailed medical history, carrying out a clinical neurological assessment, laboratory investigations, and imaging of the affected spinal segment (Table 11.8).

A neurologist and a surgeon must be consulted immediately when cauda equina symptoms and acute loss of important muscle function (foot drop) are present. Consultation with a neurologist, including an EMG assessment, is also initially necessary when less severe pareses are present, to set a baseline and monitor progress when prescribing muscle electrostimulation.

| Intervertebral disk prolapse |

| Decompensated spinal canal stenosis |

| Postsurgical: Scarring, instability (postdiscotomy and postfusion syndromes) |

| Spondylolisthesis (degenerative and isthmic) |

| Osteoporotic fracture |

| Synovial cysts |

| Considerable malpositioning due to sciatica, torticollis |

| Large prolapse with the threat of paraplegia or cauda equina symptoms |

| Motor and/or sensory deficits found in the gray area of becoming an indication for surgery |

| Mild to moderate symptoms |

| Infections, open wounds |

| Neurological seizure disorders |

| Severe conduction defects |

| Decompensated heart failure |

| Blood coagulation disorders (anticoagulant medication) |

| Known hypersensitivity to local anesthetics |

| Cauda equina symptoms, foot drop |

| Irregularities in laboratory findings |

| Weight loss |

| Further neurological symptoms |

| Bone destructions |

| History of carcinoma |

| HIV (and other systemic infections) |

| Discontent with career |

| Low occupational qualifications |

| Inability to cope with psychosocial demands |

| Emotional impairment (depression, anxiety) |

| External locus of control |

| Inappropriate beliefs about illness |

| Operant factors (primary and secondary gain due to illness) |

| Heavy smoker |

| Poor physical condition |

| Further pain that cannot be explained |

In addition to the somatic diagnostics, psychological assessment is also required. In particular, this involves assessing whether the criteria for the evolution of chronic pain (yellow flags) are present. These risk factors for the development of chronic back pain do not necessarily contra-indicate IMIST, but rather indicate the necessity for a special physical therapy and psychotherapy program (Table 11.9).

Multimodal Program

Initial Medical Intervention

Spinal injections form the central focus of the multimodal program. The spinal nerve root irritation and the accompanying severe pain should be treated with a daily injection. This mainly takes the form of cervical or lumbar spinal analgesia, but once or twice a week epidural injections using the single-shot method are substituted. These injections should be administered by the treating physician or his/her deputy in a special infiltration room or an operating room and, if possible, in the morning. The reason for this is that most patients are afraid of injections. If major interventions are completed in the morning they are over and done with early in the day, and the other components of the multimodal program can be carried on without psychological stress.

Before commencing the spinal infiltration, the treating physician should assess the patient’s current status and enquire as to how the previous day went. In the case of neurological deficits, the nerve function must also be assessed before starting further treatment. During the first medical intervention, further procedures and possible options within the multimodal program are discussed and the discharge date is set. The data obtained from the neurological assessment are added to the medical notes.

At our clinic we have tried and tested the use of specially designed treatment cards. The diagnosis and the multimodal program interventions already carried out are clearly summarized on these cards. Patients carry their cards with them, and each intervention carried out as part of the multimodal program is noted on the card each day. The treatment card is added to the patient’s medical notes at the end of treatment.

When possible, a nurse or medical assistant who usually works on the ward during the day should attend the first medical intervention. Instructions for further action—ordering consultations, imaging techniques, laboratory tests, passing on information to the physicians on the ward, etc.—are therefore not only put in writing but are also directly implemented by the assistant. The nurse or assistant is also available to the patient on the ward during the day.

Second Medical Intervention

As part of the IMIST, in addition to the daily cervical or lumbar spinal nerve analgesia, a second infiltration is planned for later in the day. There should be at least 6 hours break between injections. When the patient has mainly severe radicular symptoms arising from the anterior branch of the spinal nerve, this second infiltration can take the form of further spinal nerve analgesia. Usually the second infiltration deals with the secondary symptoms found outside the vertebral motor segment, e. g., injections into the sacroiliac joints, trigger point infiltrations, and zygapophysial joint capsule infiltrations. Acupuncture is an alternative when the patient reacts well to this form of therapy. When indicated, manual therapy is conducted by physicians as part of the daily routine.

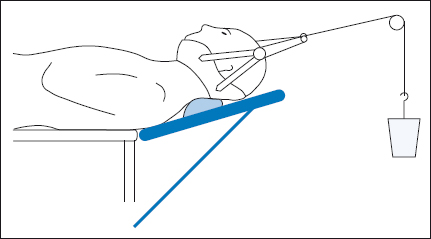

Positioning

After the spinal infiltrations, positioning the patient to relieve the spinal nerve root is the second essential therapeutic component of the in-patient spinal treatment. The patient is placed in a pain-relieving position or in Glisson traction when cervical syndromes are present between the individual treatment sessions. When the intervertebral disk tissue is displaced but the anulus fibrosus is intact, traction offers a good therapeutic opportunity for tissue to return to the center of the intervertebral disk. Glisson traction reliably achieves this in the cervical spine and the flexion cube does so in the lumbar spine.

The physician adjusts these orthopedic aids individually in relation to the clinical neurological findings. The Glisson traction should pull in the direction of relief, when possible. Manual therapy techniques are used to ascertain the appropriate direction. The Fowler position may increase symptoms in the lumbar spine. In this case, the patient should lie on one side with the hips and knees bent (Figs. 11.1, 11.2).

Pain Medication

The in-patient care of patients under continual medical supervision also permits the administration of strong analgesics (WHO level 3, see Chapter 4, “WHO Analgesic Ladder”) when severe pain is present. However, the aim of the minimally invasive spinal therapy is for patients to get by without pain-relieving medication, or with only small amounts, in conjunction with a long-term movement program. The physician reassesses the medication daily. When problem patients require long-term analgesics, the appropriate pain medication is decided upon in an interdisciplinary pain conference (see Chapter 4, “Multimodal Medication Concomitant Therapy”).

Physical Therapy

When physical therapy, thermotherapy, and electrotherapy are used in an in-patient setting, they can be integrated into the daily routine, providing useful supplements to the medical interventions. As the symptoms improve, the physical therapy progresses from exercises based on the pain-relieving position to exercises that are part of the medical training therapy, and the patient starts on an individual sport and movement program.

The movement in pain-free range (MIPFR) concept is based on the observation that movement relieves pain. The prerequisite is that movements should not increase pain, which means that the movements must be made in the parts of the body that are not affected by pain. It is for this reason that the so-called dynamic, “linear” types of sport, such as swimming, jogging, and cycling, are the main focus of the MIPFR program. In the in-patient setting, patients usually start with stationary cycling. This does not normally cause additional symptoms, even in patients with severe spinal pain syndromes.