Gunshot Wounds

Airguns:

these compressed air-driven weapons propel a small, blunt pellet that does not tend to penetrate very far, although it may severely damage the eyeball or even cause a pneumothorax.

Shotguns:

there are several different sizes of shotgun; all fire a large number of lead pellets. The wound that they create depends on the distance from the gun, as a result of the fanning out of the shot. At up to 1 m the entry wound will appear as a single hole <3 cm in diameter. At such close range widespread tissue damage and skin burns will occur. Exit wounds are uncommon. At 2 m the shot is already beginning to disperse whereas at 6 m the shot will be spread over a diameter of about 15 cm. At 12 m the pellets are scattered over an area with a diameter of around 30 cm. These are only rough guides and should not be ventured as a definitive ballistics opinion in court.

Other Firearms:

differing types of firearm cause damage proportional to the amount of energy that their bullets transfer to the tissues. Handguns usually fire a large bullet at a relatively low velocity and so result in localised damage to the structures directly in the path of the missile. Military rifles have a high muzzle velocity and cause extensive damage. The high-energy transfer from the bullet to the surrounding tissues causes a large cavity to be formed along the track, which finishes in a large exit wound. Also the missile itself may roll and shatter in the tissues.

Asphyxia

Attempted suffocation and strangulation may both cause a picture similar to traumatic asphyxia syndrome (→ p. 78). Signs of compression of the face or the neck may be present, as may the marks of a violent struggle. Hanging causes death through a mixture of asphyxia, cerebral ischaemia and spinal disruption. The asphyxia resulting from a bag over the head, seen in children and sexual asphyxia, usually causes death by hypoxia and subsequent bradycardia.

Violent Crime

Contrary to popular belief, most of the victims of violent crime who present to an ED are young men and not elderly women (→ Box 20.1). They are assaulted in a bar or a club or in the street and are often intoxicated, whereas 75% of the attacks on women occur in the home of either the victim or the assailant.

Box 20.1 Risk Factors for Violent Crime

Box 20.1 Risk Factors for Violent Crime- Male sex

- Age 16–29 years

- Low income

- Single

- Member of ethnic minority group

- Alcohol intoxication

Injuries to the face, head and hands are the most common unless weapons are used in the assault. There may be long-term psychological and psychosomatic effects including:

- depression

- loss of confidence, fear and anxiety

- irritability, decreased concentration and mood changes

- lethargy, sleep and appetite disturbances

- headaches, nausea and muscle tension

- behavioural changes (e.g. withdrawal or increased alcohol consumption).

In some cases, the problems may be so severe and prolonged as to merit a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (→ p. 369). This diagnosis would not normally be made unless symptoms persisted for at least 1 month and caused impairment of normal life functions.

Domestic Violence

More than 25% of all violent crime reported to the police is domestic violence of men against women, making it the second most common violent crime in the UK. It is thought to account for around 1% of all ED attendances. Up to one in four women will be physically assaulted by a partner during her lifetime and around one in ten will suffer an attack each year. It is estimated that a woman in an abusive relationship will suffer over 30 physical assaults before disclosing the abuse – usually when asked directly. Patterns of presentation with sufficient sensitivity to identify victims of domestic violence are few but facial bruising should always alert suspicion. Deliberate self-harm and pregnancy are associated with all types of abuse:

- Severe, repeated violence occurs in at least 5% of all long-term relationships in Britain. It affects women of all cultures, religions, ages and social groups.

- Over 45% of all murdered women are killed by their male partners; this amounts to one or two women per week in the UK. Women who leave their abusers are at a 75% greater risk of being killed than those who stay.

- Nearly half of all assaults against women are committed by a partner or former partner, compared with 4% of assaults against men.

Abuse may be:

- psychological – shouting, swearing, humiliation or enforced isolation from family and friends

- economic – withholding of money and transport

- sexual

- physical.

Physical injury is the most likely form of domestic violence to present to an ED. The following are possible signs of it:

- Delayed presentation of injuries

- Injuries that are inconsistent with the mechanism described in the history

- Multiple injuries, especially when symmetrically distributed or of differing ages

- Injuries such as bites, burns, scalds or bruises

- Injuries on areas of the body that are normally clothed

- Injuries to the face, neck, breasts, genitals or pregnant abdomen

- Perforated eardrums or detached retinas

- Evidence of rape or other sexual assault

- Pelvic pain

- Multiple somatic complaints

- Psychiatric illness

- Drug abuse.

TX

Injuries should be treated appropriately and social services contacted for advice and shelter if necessary. Specialist helplines to various organisations are now available. A friend or relative of the victim should be enlisted for support and enquiries made about the current safety of any children in the family. (The risks of violence to children growing up in an abusive household are substantial. Such children are much more likely than most to be listed on the Child Protection Register. Concerns about the welfare of children should lead to immediate contact with local child protection services.) The police can be involved only with the consent of the injured party.

Rape and Sexual Assault

Around 17% of women and 3% of men in the UK state that they have been subjected to non-consensual sexual experiences as adults. About two-thirds of assaults of this type are committed by someone known to the victim. The experience of sexual violence can be life threatening and degrading. Not surprisingly, psychological upset and a specific form of PTSD (rape trauma syndrome) are common sequelae. Not all patients who have been sexually assaulted have visible genital (or oral) injuries, although around 50% have other physical injuries. Examination should be left to the police surgeon because forensic evidence will need to be collected in a way that does not contaminate it or render it invalid as evidence. Locard’s principle states that ‘every contact leaves a trace’. This includes ED staff!

TX

There should be early involvement of social services; there may be a dedicated rape crisis centre. Specialist police officers are allocated to this type of investigation.

Drug-Assisted Sexual Assault

Alcohol (self-administered or in laced drinks) is by far the most common drug to be associated with sexual assault. However, gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), ketamine, flunitrazepam and zopiclone have all been reported as being used to facilitate sexual assault. Patients drugged and assaulted in this way present a very difficult problem because they will have an impaired memory of events and may just feel that ‘something wrong happened’.

Child Abuse

Abuse of Elderly People

Physical abuse of elderly people is surprisingly common; neglect and emotional abuse are even more common. The recent increase in the number of small, privately run nursing homes has done nothing to decrease the problem. Signs may be minimal or similar to those of other forms of domestic violence (→ p. 372). As soon as the diagnosis is suspected, advice should be sought from social workers and senior geriatricians.

Victim Support and Counselling

Details of local victim support schemes and the witness support service in the Crown Court can be found in the telephone directory, although the police will usually negotiate contact if asked. Victim Support (a registered UK charity) can help with:

- practical matters such as insurance and compensation

- personal and emotional support

- liaison with the police and other agencies

- explanation of the criminal justice system

- witness support.

People suffering from PTSD or depression should be referred to psychiatric services. Counselling is often advised (→ p. 369).

ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUGS/FITNESS TO DRIVE

Misuse of Drugs

The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 prohibits certain activities in relation to ‘Controlled Drugs’, in particular their manufacture, supply and possession. The penalties applicable to offences that contravene the Act are graded according to the harmfulness attributable to a drug when it is misused. For this purpose, the controlled drugs are divided into three classes called A, B and C (→ Box 20.2). The Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001 define the classes of people who are authorised to supply and possess controlled drugs while acting in a professional capacity and lay down the conditions under which their activities may be carried out. In these regulations, drugs are divided into five schedules, each with its own specific legal requirements (→ Box 20.2).

Box 20.2 The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001

Box 20.2 The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001- Section 4 (2) Production of a controlled drug (i.e. Schedule 1, 2 and 3 drugs)

- Section 4 (3) Supplying or offering to supply a controlled drug

- Section 5 (2) Having possession of a controlled drug without a prescription or other authority

- Section 5 (3) Having possession of a controlled drug with intent to supply it to another person

- Section 6 (2) Cultivation of a cannabis plant

- Section 8 Being the occupier or manager of premises and knowingly permitting or suffering:

- the production or attempted production of controlled drugs

- the supply, attempt to supply or offer to supply a controlled drug to another person

- the preparation of opium for smoking

- the smoking of cannabis, cannabis resin or prepared opium

- the production or attempted production of controlled drugs

- Class A includes: cocaine, LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), diamorphine, morphine, pethidine, methadone, opium, MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamfetamine or ecstasy), methamfetamine, phencyclidine and class B substances when prepared for injection

- Class B includes: codeine, standard amfetamines and barbiturates

- Class C includes: buprenorphine, cannabis, cannabis resin, most benzodiazepines, zolpidem, anabolic steroids and some hormones

- Schedule 1 includes: cannabis, LSD and other drugs that are not used medicinally

- Schedule 2 includes: diamorphine, morphine, pethidine, cocaine, amfetamine and secobarbital

- Schedule 3 includes: buprenorphine, most barbiturates and temazepam

- Schedule 4 includes: benzodiazepines (except temazepam), zolpidem, anabolic steroids and some hormones

- Schedule 5 includes: those preparations that (because of their strength) are exempt from virtually all controlled drug requirements

The Misuse of Drugs (Supply to Addicts) Regulations 1997 instruct that only those medical practitioners who hold a special licence from the Home Office may prescribe, administer or supply diamorphine, dipipanone or cocaine in the treatment of drug addiction. This does not apply to the prescription of these drugs to known addicts for the relief of pain from organic disease or injury. Nor does it apply to methadone or dihydrocodeine.

In England, health professionals are expected to report cases of drug misuse to their regional drug misuse centre as part of the National Drugs Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS). Wales and Scotland have a similar national reporting system. All three countries require notification of misuse of all types of drugs including opiates, benzodiazepines and central nervous system (CNS) stimulants. In Northern Ireland, the Misuse of Drugs (Notification of and Supply to Addicts) (Northern Ireland) Regulations 1973 require doctors to send particulars of people whom they consider to be addicted to controlled drugs to the Department of Health and Social Services.

Alcohol and Trauma

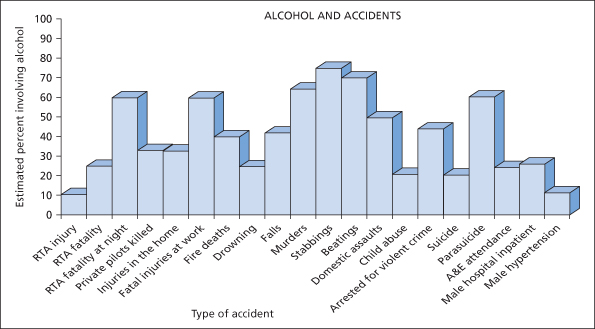

Ethyl alcohol is probably the most dangerous substance in the world. It is freely available in many societies and, unlike other psychotropic drugs, it is dispensed by a barman rather than by a pharmacist. It is so frequently involved in the causation of accidents that no discussion of the work of an ED would be complete without it. In the UK, a tenth of all road accidents that result in injury are a result of the effects of excess alcohol in the blood and almost all other injuries have a significant association with alcohol usage (→ Figure 20.1).

Measurement of Alcohol in the Human Body

Units of Alcohol

A unit of alcohol has become the standard measure by which public health information on alcohol consumption is expressed. It is defined as 10 mL by volume (58 g by weight) of pure alcohol – roughly the alcohol content of a standard measure of 25 mL of many spirits. Half a pint of beer (3% strength) or a glass of wine (125 mL of 8% alcohol) is also roughly equivalent to 1 unit. Within the first hour, a unit of alcohol increases the blood level by approximately 15 mg/dL in an average man.

Elimination of Alcohol

In a healthy person, about 90% of ingested alcohol is cleared from the blood by the liver. This occurs at a steady rate of about 15 mg/dL per h.

Laboratory Units of Alcohol

Several units of blood alcohol measurement are in use worldwide including milligrams/litre and millimoles/litre. The unit used in UK legal practice, although not necessarily in hospital laboratories, is milligrams/decilitre (i.e. mg/dL or mg% – 1 dL is 100 mL) (legal limits for drivers → Box 20.3).

Box 20.3 Legal Limits of Alcohol for Drivers in the UK

Box 20.3 Legal Limits of Alcohol for Drivers in the UKConventionally, breath alcohol levels are converted to equivalent blood alcohol levels by multiplying by a factor of 2300. The comparison is not strictly accurate because alcohol concentration in the breath rises faster and falls earlier than it does in venous blood.

Requests for Specimens for Analysis from Patients in Hospital

The Police Reform Act 2002 provided new powers concerning the taking of blood specimens from patients involved in road traffic accidents to test for levels of alcohol or drugs. As before, while a person is in hospital (as a patient!), he or she is not required to provide a specimen for breath or laboratory testing unless the medical practitioner in immediate charge of the case has consented. (It must be remembered, however, that there are very few medical circumstances that preclude sampling.) If there is no clinical objection, then a person from whom a police constable requires a blood sample and who (without reasonable excuse) refuses to consent commits an offence. Under the previous legislation, it was a statutory requirement to obtain consent for blood sampling from the person concerned. Therefore, when a patient lacked capacity to consent (usually because of a depressed level of consciousness), a specimen could not be obtained. This led to people escaping prosecution for very serious offences, such as causing death by careless driving while under the influence of alcohol.

The provisions of the Police Reform Act aimed to eliminate this inequity between those with capacity to consent and those without it. A police constable may now request that a blood sample be taken from a patient who, for medical reasons, is incapable of giving consent. This request would normally be made to a police surgeon but, in exceptional situations, may be made to another medical practitioner who is not directly involved in the clinical care of the patient. If the doctor considers it appropriate to take the specimen, then the police constable will provide a special kit to be used for this purpose. The location of all forensic specimens is required by law to be recorded at all times – ‘the chain of custody’. As soon as possible, the police will inform the patient that a blood sample has been taken and obtain his (or her) consent for it to be analysed. In this case, failure to give permission for analysis may render the person liable to prosecution.

Driving and Other Drugs

Many drugs may impair the ability of a patient to drive or to operate machinery. Drowsiness and impaired psychomotor performance are the most common drug-related effects to interfere with driving, but postural hypotension, fatigue, hypoglycaemia and impaired vision may also occur. Drivers taking minor tranquillisers or tricyclic antidepressants are two to five times more likely to be involved in an accident than untreated control individuals. The early stages of treatment are associated with the highest risk and the effects of centrally acting drugs are often potentiated by alcohol.

As a result of these risks, patients must always be warned whenever their treatment could alter their ability to drive or perform other activities safely. A recommended list of advice is given in Box 20.11 on p. 390.

Driving and Medical Conditions

Medical conditions in drivers contribute to about 1% of the road accidents in the UK that result in injury or death (→ Box 20.4).

Box 20.4 Most Common Causes of Collapse at the Wheel

Box 20.4 Most Common Causes of Collapse at the Wheel- Fits

- Unspecified blackouts

- Hypoglycaemia

- Myocardial infarction

- Strokes

There are two sets of medical criteria for fitness to drive: one for an ordinary licence and another for a vocational licence (i.e. for a passenger-carrying vehicle [PCV] or for a large goods vehicle [LGV]). Licence holders have a statutory obligation to notify the licensing authority as soon as they become aware that they have any condition that might affect safe driving, unless the condition is not expected to last more than 3 months. Failure to notify is a legal offence.

The Road Traffic Act 1988, Section 92, lists prescribed disabilities that bar the sufferer from driving. They are:

In practice, a person with any of these conditions can drive once he or she has satisfied the licensing authority that he or she does not present any significant risk. The rules for vocational drivers are more stringent. Vocational licence holders are responsible for more than twice as many accidents that result in serious injury or death as ordinary car drivers, even when the statistics are corrected for mileage.

For the purposes of the ED, patients should be advised to (temporarily) refrain from driving whenever there is a possibility of a condition being diagnosed that could make driving or other complex tasks dangerous to themselves or others. Such problems may include:

- fits

- blackouts other than simple faints

- dizziness and vertigo

- head injury

- sudden cardiac dysrhythmias

- myocardial infarction

- CVAs (cerebrovascular accidents) and TIAs (transient ischaemic attacks)

- application of an eye pad in the ED (→ p. 412)

- decreased ability to use a limb (e.g. forearm in plaster)

- post-sedation or strong analgesia (→ p. 15).

Driving, or other prohibited activities, should only be recommenced when:

- the condition has resolved completely

- the diagnosis has been ruled out after specialist investigation

- the condition has been controlled and a symptom-free period has elapsed.

In the UK, the Medical Advisory Branch of the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority (DVLA) in Swansea supplies written and verbal advice for doctors on all aspects of fitness to drive.

Payment for Emergency Treatment of Patients Involved in Road Traffic Accidents

The Road Traffic (NHS Charges) Act of 1999 allows hospitals to recover some of their costs for treating the victims of motor vehicle accidents from the insurers of the drivers involved. The value of this system to any particular hospital usually depends on the efficacy of local data collection systems.

LEGAL ISSUES

Consent

In the competent adult, treatment can be given only if the patient gives consent. Any physical contact or treatment without this consent may be construed as trespass or battery. These legal torts do not require harm to have resulted to the patient. Consent may be given verbally, in writing, by gestures or by actions. A signature on a consent form does not by itself prove that consent was valid. In addition, the following points should be noted:

- Valid consent or refusal is dependent on a patient’s ability (capacity) to make decisions, namely to:

- Capacity to give meaningful consent or make a valid refusal is a legal concept and not a medical one, and is governed by the following laws:

However, these laws presuppose that all registered medical practitioners are qualified to make an assessment of capacity. It also assumes that all adults have the capacity to consent or refuse unless proven otherwise.

- Patients may be competent to make some health-care decisions, even if they are not competent to make others.

- Consent is valid only if the patient understood to what he or she was consenting (i.e. gave informed consent). However, a doctor must provide only that information about a procedure and its attendant risks that a reasonable group of doctors would disclose in the same circumstances. The concepts of the ‘reasonable man’ and ‘the responsible body of medical opinion’ pervade this type of law. Compliance with the latter tenet forms the basis of the so-called Bolam test.

- The patient’s right to self-determination takes precedence over the physician’s duty to preserve life. A competent adult has the right to refuse any treatment or investigation even if it puts his or her life or health at risk. The patient has no obligation to justify this decision with valid and rational argument. The only exception to this rule is where treatment is for a mental disorder and the patient is detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 – and most such patients will lack the capacity to make decisions.

- A competent pregnant woman may refuse any treatment, even if this would be detrimental to the fetus.

- No one can give consent on behalf of an incompetent adult. However, such patients may still be treated provided that the proposed treatment is in their ‘best interests’ (England and Wales) or ‘to the patient’s benefit’ (Scotland). ‘Best interests’ extend wider than best medical interests to include such factors as previous wishes and beliefs and general wellbeing. People close to the patient may be able to provide valuable information on some of these factors. Where a patient has never been competent, relatives, carers and friends may be best placed to advise on the patient’s needs and preferences.

- An incompetent patient who has indicated in the past (while competent) that they would refuse treatment in certain circumstances (‘an advance refusal’) must not be treated should those circumstances arise.

- Consent obtained by deceit or with unreasonable pressure is invalid.

- Consent may be withdrawn at any time.

Treatment Under Common Law

A patient who is incapable of giving consent (e.g. in cardiac arrest or coma) may be treated under common law. This means that, so long as staff perform only those procedures, which are reasonable to protect life and limb, then they are not liable to be sued for assault. Furthermore, to do less than this would be to neglect their duty of care. The law requires that all decisions must be made in accordance with the patient’s best interests. Section 62 of the Mental Health Act 1983 codifies in statute this long-accepted practice.

Emergency Treatment

The emergency treatment of physical and psychiatric problems in a fully conscious patient who cannot or will not give informed consent is an extremely difficult area. Treatment cannot be given without a patient’s consent unless, by virtue of an abnormal mental state, he or she is incompetent to give or withhold consent. The difficulty is in deciding, in the acute situation, which patients are competent in the eyes of the law and which are not. In general, patients with frank psychotic symptoms can be detained and sedated under common law (→ above). Others are likely to be competent, even if depressed or agitated. The help of relatives and psychiatric specialists should be enlisted as soon as possible. Detailed records are essential.

Deprivation of Liberty

In the past decade, people with learning difficulties, as well as some elderly and infirm people, have been the subject of rulings by the European Court of Human Rights that they have been unlawfully deprived of their liberty, contrary to Article 5[1] of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. This is a very difficult and grey area but factors that suggest deprivation of liberty may include the following:

- Restraint, including sedation, is used to admit a person to an institution where that person is resisting admission.

- Staff exercise complete and effective control over the care and movement of a person for a substantial period.

- Staff control assessments, treatment, contacts and residence.

- A decision has been taken by the institution that the person will not be released into the care of others, or permitted to live elsewhere, unless the staff in the institution consider it appropriate.

- A request by carers for a person to be discharged to their care is refused.

- The person is unable to maintain social contacts because of restrictions placed on his or her access to other people.

- The person loses autonomy because they are under continuous supervision and control.

The Mental Capacity Act (England and Wales) 2005 and the Adults with Incapacity Act (Scotland) 2000 provide strict rules about the capacity of adults to make their own decisions. There is also a judicial ‘Court of Protection’ that exists specifically to arbitrate about such matters.

Blood Transfusion for Jehovah’s Witnesses

There are 140 000 Jehovah’s Witnesses in the UK and Ireland; their faith does not allow them to accept the transfusion of blood or its primary components. Administration of blood in the face of a refusal by an informed and rational patient is obviously unlawful. Similarly, if written evidence in the form of a signed and witnessed advance directive exists, this should be acted upon. Such directive cards are commonly carried by Jehovah’s Witnesses and usually state that the physician is released from liability if harm results from failure to transfuse. In the absence of verbal or written instructions from the patient, clinical judgement should take precedence over the opinion of relatives or friends.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree