30 Maxillofacial Disorders

• Temporomandibular joint dislocation is usually readily reduced in the emergency department after the patient has been pretreated with analgesic and antispasmodic agents.

• Epistaxis may be the initial complaint of a patient with a more serious systemic illness, such as a clotting disorder.

• When visible blood loss from the nasopharynx has been stopped, the clinician should examine the posterior oropharynx for ongoing occult blood loss.

• Posterior epistaxis accounts for about 10% of nasal hemorrhages and can result in large volumes of blood loss.

• Any abnormal neurologic or ocular physical findings in a patient with rhinosinusitis mandate further investigation to assess for central nervous system extension of the disease.

Temporomandibular Disorders

Epidemiology

The temporomandibular articulations are unique within the body in that they are bilateral joints that are nearly continuously in use. Consequently, the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is subject to both pain and dislocation. Discomfort of the TMJ was previously referred to as TMJ pain dysfunction syndrome. However, because it was realized that more than just the actual joint can be the source of a patient’s discomfort, the term has evolved to temporomandibular disorder (TMD). TMD is defined as craniofacial pain that involves the TMJ, masticatory muscles, and associated head and neck musculoskeletal structures.1 It is roughly estimated that more than 10 million people in the United States alone have symptomatic TMD.2 Most of those affected are women.

TMJ dislocation is an uncommon disorder, with one case series reporting 37 occurrences in 700,000 patient visits.3

Pathophysiology

TMD is probably due to excessive strain on the muscles of mastication with resultant strain on the capsular ligaments of the TMJ.4 The result is that the mandibular condyle does not articulate properly in its joint. The patient feels pain and senses an occlusal disturbance.

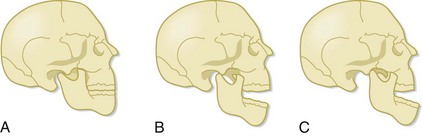

Patients with TMJ dislocation are unable to close their mouth. With normal function, when the mandible is open, the mandibular condyle moves anteriorly and inferiorly. When the mandible closes, the condyle moves posteriorly and superiorly and returns to its original location (Fig. 30.1). TMJ dislocation results when the mandibular condyle moves anterior to the temporal eminence (the anterior portion of the mandibular fossa) (see Fig. 30.1). Once the dislocation occurs, the muscles of mastication spasm, which results in trismus and inability of the patient to return the mandibular condyle to its anatomic position. The dislocation usually results from excessive opening of the mouth, such as occurs with yawning or laughing. TMJ dislocation can also be the result of trauma, seizure, or dystonic drug reactions.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Unilateral pain in the region of the TMJ and clicking or crepitance that is exacerbated by chewing are the classic complaints of a patient with TMD (Box 30.1). The dull or throbbing pain is localized to the preauricular region or to the muscles of mastication and typically worsens with movement of the mandible, such as when eating or talking. Pain may be most severe in the morning if bruxism is an issue.5 If a click is present, the patient hears it when jaw opening is initiated. The pain may also radiate to the neck, ears, mandible, or temporal region.

An inability to close the mouth following extreme jaw opening, such as yawning, is the classic manifestation of TMJ dislocation. If the dislocation is unilateral, the mandible will deviate away from the side of the dislocation (Box 30.2).

Treatment

Temporomandibular Disorders

Pain should be addressed with antiinflammatory agents (e.g., ibuprofen, 600 mg by mouth every 6 hours, or naproxen, 500 mg by mouth every 12 hours) and narcotic pain medications (e.g., oxycodone, 5 to 10 mg by mouth every 6 hours as needed). Warm compresses should also be applied to the TMJ region for 15 minutes three times per day. Benzodiazepines are used to relieve masseter muscle spasm (e.g., diazepam, 5 mg by mouth every 8 hours as needed). Behavioral modifications include minimizing masseter muscle use through a soft diet and cessation of gum chewing. Reassurance is important because up to 40% of patients will experience resolution of their TMD symptoms with little or no treatment (Box 30.3).6

If bruxism is suspected, dental follow-up should be arranged, and a bite appliance can be considered. To date, experimentation with the use of botulinum toxin to reduce masseter muscle contractility and strength has yielded mixed results.7

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Temporomandibular Disorders

Take antiinflammatory and pain medications as prescribed.

Apply warm compresses in front of your ear for 15 minutes 3 times per day.

Benzodiazepines may have been prescribed to control muscle spasm. These drugs may cause sedation.

Eat only soft foods until the symptoms resolve.

See your dentist for follow-up to evaluate whether bruxism is the cause of your condition.

Many cases resolve spontaneously and very few require aggressive treatment.

See your doctor or return to the emergency department if your pain is not controlled or if you are unable to fully open or close your mouth, which may indicate a dislocation of your jaw.

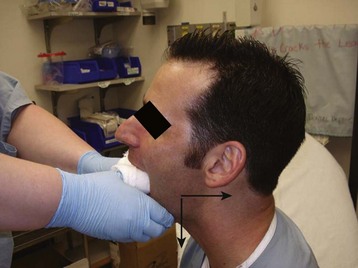

Temporomandibular Dislocation

Once the patient is comfortable, the clinician faces the patient and grasps the mandible inferiorly with the fingers of both hands. The clinician’s thumbs should be heavily wrapped in gauze for protection and then placed on the occlusive surfaces of the mandibular molars. Downward pressure is applied to move the mandibular condyle inferior to the temporal eminence. The mandible is then pushed posteriorly (Fig. 30.2). Once the condyle is posterior to the temporal eminence and pressure is released, the condyle returns to its anatomic position in the mandibular fossa. At the time of reduction, the masseter muscles may contract forcefully and cause the patient to inadvertently clench the jaw. The clinician must be aware of this possibility and ensure that the thumbs are guarded during the procedure and remove the thumbs from the occlusive surface of the molars as quickly as possible. If this method does not work, both thumbs may be placed simultaneously on the dislocated side and the reduction reattempted.8

In an effort to minimize risk to the practitioner, an extraoral approach to TMJ reduction was proposed by Chen et al. in 2007.9 The physician faces the patient and places a thumb on the palpable coronoid process that is displaced anteriorly. The fingers of that hand are placed on the mastoid process for stability. On the nondislocated side, the thumb is placed on the zygoma and the fingers hold the mandible angle. The nondisplaced side of the mandible is pulled anteriorly while concomitant pressure is applied posteriorly to the displaced coronoid process. Although this approach is less successful than the traditional approach, there is no risk of injury to the practitioner.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Temporomandibular Joint Dislocation

Avoid excessive mouth opening, including laughing and yawning, to prevent recurrence of the dislocation.

Take pain medications and muscle relaxants as prescribed. These drugs may cause sedation.

Follow up with an oromaxillofacial surgeon within 2 weeks.

Return to the emergency department if your pain is not controlled or if you are unable to fully close your mouth, which may indicate a recurrent dislocation.

Epistaxis

Epidemiology

The incidence of epistaxis is unknown, but it is estimated to occur in up to 60% of all individuals. The vast majority of these episodes are self-limited and only 6% require medical attention.10 Epistaxis affects both adults and children, with a higher incidence in children younger than 10 years and adults older than 35 years.11

Pathophysiology

The nasal mucosa is a highly vascular area, and any disruption of the mucosa can result in bleeding. Although epistaxis can be caused by trauma, this is not the most common cause. Bleeding more commonly results from upper respiratory infections (URIs), a dry environment, nasal foreign bodies, allergic rhinitis, nasal mucormycosis, topical nasal medications (including antihistamines and corticosteroids), and drugs taken intranasally such as cocaine (Box 30.4). Additionally, epistaxis may be the initial symptom of a primary or secondary systemic bleeding disorder. One study found that 45% of patients with bleeding severe enough to warrant hospitalization had an associated systemic disorder that may have contributed to the epistaxis.12

Box 30.4 Risk Factors for Epistaxis

The relationship of hypertension to epistaxis is controversial. It is unclear whether elevated blood pressure is the cause or the effect of epistaxis; therefore, hypertension alone is not known to be an independent risk factor for nasal hemorrhage.13–15

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Obtaining a detailed history is often the key to determining the cause of the patient’s epistaxis. The clinician must know whether the patient has recurrent epistaxis, easy bruising, or other sources of bleeding, such as when shaving or brushing the teeth, or is taking a platelet inhibitor or anticoagulant medication. The past medical history is important in a patient who has hepatic disease, atherosclerosis, Osler-Weber-Rendu disease (hemorrhagic telangiectasia), diabetes mellitus, or cancer with ongoing chemotherapy treatment because each of these conditions is a risk factor for epistaxis.16 Women are more prone to epistaxis during pregnancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree