Fig. 57.1

“Blackwater Fever” – Urine sample showing dark urine due to hemoglobinuria (right tube)

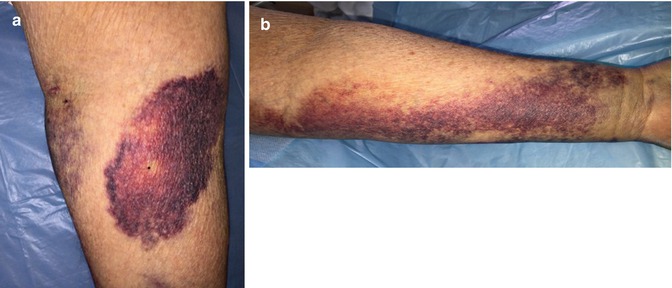

Fig. 57.2

(a, b) Ecchymosis from thrombocytopenia

Question

What are the challenges in the diagnosis and management of the returning traveller with severe malaria?

Answer

People now move across the world with great facility, whether on vacation or business. Endemic diseases, such as malaria, can affect the travelers upon return to home. Malaria.com maps the regions of the world where Plasmodium falciparum, the type intensivists might encounter, may be transmitted [1].

In a returning traveler, fever can be a benign and self-limiting infection, but initially must be considered seriously. Table 57.1 displays the top illnesses encountered in returning travelers. In order to make a diagnosis a comprehensive history with details regarding places visited, duration, purpose, activities undertaken, any chemoprophylaxis taken before or while traveling is critical for the initial work-Up. Knowledge of incubation period and disease risk by geographic are helps in making a differential diagnosis. Table 57.2 displays various diseases potentially encountered by the returning traveler by the duration of incubation period.

Table 57.1

Top illnesses in returning travelers

Diagnosis | % |

|---|---|

1. Systemic Illnesses | 35 |

Malaria | 21 |

Malaria due to P Falciparum | 14 |

Malaria due to P Vivax | 6 |

Malaria due to other species | 2 |

Dengue | 6 |

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi or paratyphi | 2 |

Rickettsia | 2 |

2. Acute diarrhea | 15 |

3. Respiratory illness | 14 |

4. Genitourinary diseases | 4 |

5. Gastro intestinal illness | 4 |

Table 57.2

Incubation period of various diseases potentially encountered in returning travelers

Incubation period | Diseases |

|---|---|

<7 days | Common: Malaria, Traveler’s diarrhea, dengue, enteric fever, respiratory tract infection Others: rickettsiosis, leptospirosis, meningitis, yellow fever, arbovirus, meningococcal |

7–21 days | Common: Malaria, enteric fever Others: rickettesioses, viral hepatitis, leptospirosis, HIV, Q Fever, brucellosis, African Trypanosomiasis |

>21 days | Common: Malaria, Enteric Fever Others: tuberculosis, hepatitis B virus, bacterial endocarditis. HIV, Q fever, brucellosis, amebic liver diseases, melioidosis. |

Principles of Management in Severe Falciparum Malaria

Patients with severe malaria usually present with a high level of parasitemia and/or major signs of organ dysfunction. Populations at greatest risk for severe falciparum malaria are young children, pregnant women and travelers to endemic areas. In endemic areas, elder children and adults develop partial immunity after repeated infections and are at relatively low risk for severe disease. Travelers to areas where malaria is endemic generally have no previous exposure to malaria parasites and are at high risk for severe disease. Pregnant women are more likely to develop severe P. falciparum malaria than other adults, particularly in the second and third trimesters. Complications such as hypoglycemia and pulmonary edema are more common than in non-pregnant individuals. Maternal mortality can approach 50 %, and fetal death and premature labor are common [2].

Patients with severe malaria represent a clinical challenge for the clinician given the complex pathophysiology of the infection involving multiple organ systems. Seizures and severe anemia are relatively more common in children, whereas hyperparasitemia, acute renal failure, and jaundice are more common in adults. Cerebral malaria (with coma), shock, acidosis, and respiratory arrest may occur at any age [2–4].

Definition of Severe Malaria

Severe malaria is generally defined as acute malaria with high levels of parasitemia (>5 %) and/or major signs of organ dysfunction

- 1.

Altered consciousness with or without convulsions

- 2.

Use of accessory muscles, nasal alar flaring, Tachypnea.

- 3.

Metabolic acidosis (plasma bicarbonate M 15 mmol/L or whole blood lactate >5 mmol/L)

- 4.

Circulatory collapse

- 5.

Pulmonary edema or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- 6.

Renal failure, hemoglobinuria (“Blackwater Fever”)

- 7.

Jaundice

- 8.

Disseminated Intravascular coagulation

- 9.

Severe Anemia

- 10.

Hypoglycemia

Diagnosis

The clinician must have a high index of suspicion for malaria in travelers presenting with fever and a history of travel to malaria endemic regions within the previous year and especially in the prior 3 months. In uncomplicated malaria apart from fever, patients usually present with nonspecific clinical features. If the diagnosis of falciparum malaria has been delayed, a seemingly well-appearing patient may rapidly deteriorate and present with jaundice, confusion, or seizures and have a high fatality rate. Hence, it is critical to make a rapid and accurate diagnosis when malaria is suspected clinically [3, 4].

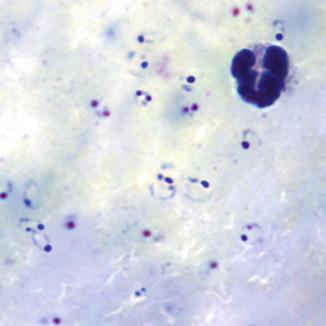

Microscopy is the gold standard and preferred option for the diagnosis of malaria. In most cases the examination of thin and thick blood films will reveal Malaria parasites (Figs. 57.3 and 57.4).

Thick films are more sensitive to detect low levels of parasitemia. In general the greater the parasite density in the peripheral blood, the higher likelihood that severe disease is present or will develop, especially in immunocompromised patients. Thick smears are more sensitive diagnostically but the thin smear subsequently helps in determining the malaria species and the level of parasitemia (the percentage of a patient’s red blood cells that are infected with malaria parasites).

Clinical Management

General Principles

Most of the time uncomplicated malaria have a good prognosis with a fatality case less 0.1 %. Uncomplicated malaria caused by P. ovale, P. vivax, and P. malariae can usually be managed with oral drugs on an outpatient basis, unless a patient has other comorbidities or is unable to take drugs orally [4, 5].

Due to little immunity against these infections, P. falciparum infections in travelers can rapidly progress to severe illness or death in as little as 1–2 days, so prompt assessment and initiation of antimalarial therapy is essential. Patients should be evaluated with attention to findings consistent with malaria as well as additional and/or alternative causes of presenting symptoms. Of primary importance in the treatment of malaria is the provision of prompt, effective therapy and concurrent supportive care to manage life-threatening complications of the disease. Supportive measures, such as fluid management, oxygen, ventilatory support, cardiac monitoring, and pulse oximetry, should be instituted as needed. During this time, intravenous access should be obtained immediately. Point-of-care testing can be used for rapid determination of hematocrit [packed cell volume (PCV) or hemoglobin (HemoCue)], glucose, and lactate. Parasitemia can also be determined quickly but requires a microscope. Additional tests can be done if/when indicated: electrolytes, full blood count, type and cross, blood culture, and clotting studies. Unconscious patients should have a lumbar puncture to rule out concomitant bacterial meningitis in the absence of contraindications (i.e., papilledema). These tasks should overlap with institution of antimalarial treatment as well as other ancillary therapies as needed (including anticonvulsants, intravenous glucose and fluids, antipyretics, antibiotics, and blood transfusion) [6, 7].

Repeat clinical assessments should be performed every 2–4 h for prompt detection and management of complications in an intensive care setting, if possible. If the Glasgow Coma Score (or in children the Blantyre coma score [see Table 57.3]) decreases after initiation of treatment, investigation should focus on the possibility of seizures, hypoglycemia, or worsening anemia. Repeat laboratory assessments of parasitemia, hemoglobin/hematocrit, glucose, and lactate should be performed in 6-h intervals. A flow chart summarizing the vital information may be used to guide management decisions [6–8].

Table 57.3

Blantyre coma score

Type of response | Response | Score |

|---|---|---|

Best Motor | Localize painful stimulus | 2 |

Withdraws limbs from pain | 1 | |

Nonspecific or absent response | 0 | |

Verbal | Appropriate cry | 2 |

Moan or innapropiate cry | 1 | |

None | 0 | |

Eye movements | Eg: directed (follows mother’s face) | 1 |

Not directed | 0 | |

Total | 0–5 |

Important independent predictors for fatality among African children with severe malaria include acidosis, impaired consciousness (coma and/or convulsions), elevated blood urea nitrogen, and signs of chronic disease (lymphadenopathy, malnutrition, candidiasis, severe visible wasting, and desquamation). Clinical features previously identified as being poor prognostic features that did not correlate with mortality in this study included age, glucose level, axillary temperature, parasite density, and Blackwater Fever [9–11].

Careful observation and thoughtful responses to changes in clinical status are the most important elements in looking after patients with severe malaria. Patients can make remarkable recoveries, and the time and effort to address the components of clinical care described in the following sections can reap tangible rewards in a relatively short period of time.

Clinical evaluation includes full physical exam, a complete neurologic examination, calculation of Glasgow or Blantyre coma score (Table 57.3), and funduscopic evaluation. Malarial retinopathy is pathognomonic for cerebral malaria in patients who satisfy the standard clinical case definition (Fig. 57.5).

Fig. 57.5

Photograph of the retina in patient with malaria, which shows exudates (arrowheads), hemorrhages (thick arrows) and changes in the color of the blood vessels (thin arrows) (From Mishra and Newton [24]. Reprinted with permission from Nature Publishing Group)

Patients with altered sensorium should undergo lumbar puncture (in the absence of contraindications) to exclude concomitant bacterial meningitis. If clinical instability or papilledema on ocular fundus examination preclude lumbar puncture, presumptive antibiotic therapy for bacterial meningitis should be initiated. Usual findings are: mean opening pressure about 16 cm of CSF, slightly elevated total protein level and cell count.

Antimalarial Therapy (See Treatment Table 57.4)

Table 57.4

Treatment of malaria

Clinical diagnosis/Plasmodium species | Region infection acquired | Recommended drug and Adult dosea | Recommended drug and pediatric Dosea Pediatric dose should NEVER exceed adult dose |

|---|---|---|---|

Uncomplicated malaria/P. falciparum or species not identified If “species not identified” is subsequently diagnosed as P. vivax or P ovale: see P. vivax and P ovale (below) re. treatment with primaquine | Chloroquine–resistant or unknown resistance b (All malarious regions except those specified as chloroquine-sensitive listed in the box below.) | A. Atovaquone–proguanil (Malarone™)c Adult tab = 250 mg atovaquone/100 mg proguanil 4 adult tabs po qd × 3 days | A. Atovaquone–proguanil (Malarone™)c Adult tab = 250 mg atovaquone/100 mg proguanil Peds tab = 62.5 mg atovaquone/25 mg proguanil 5–8 kg: 2 peds tabs po qd × 3 days 9–10 kg: 3 peds tabs po qd × 3 days 11–20 kg: 1adult tab po qd × 3 d 21–30 kg: 2 adult tabs po qd × 3days 31–40 kg: 3 adult tabs po qd × 3days >40 kg: 4 adult tabs po qd × 3days |

B. Artemether–lumefantrine (Coartem™)c 1 tablet = 20 mg artemether and 120 mg lumefantrine A 3-day treatment schedule with a total of 6 oral doses is recommended for both adult and pediatric patients based on weight. The patient should receive the initial dose, followed by the second dose 8 h later, then 1 dose po bid for the following 2 days. 5 – <15 kg: 1 tablet per dose 15 – <25 kg: 2 tablets per dose 25 – <35 kg: 3 tablets per dose ≥35 kg: 4 tablets per dose | |||

C. Quinine sulfate plus one of the following: Doxycycline, Tetracycline, or Clindamycin Quinine sulfate: 542 mg base (=650 mg salt)d po tid × 3 or 7 dayse Doxycycline: 100 mg po bid × 7 days Tetracycline: 250 mg po qid × 7 days Clindamycin: 20 mg base/kg/day po divided tid × 7 days | C. Quinine sulfate d plus one of the following: Doxycycline f, Tetracycline f or Clindamycin Quinine sulfate: 8.3 mg base/kg (=10 mg salt/kg) po tid × 3 or 7 dayse Doxycycline: 2.2 mg/kg po every 12 h × 7 days Tetracycline: 25 mg/kg/day po divided qid × 7 days Clindamycin: 20 mg base/kg/day po divided tid × 7 days | ||

D. Mefloquine (Lariam™ and generics)g

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|