111 Male Genitourinary Emergencies

• The five major male genitourinary emergencies are testicular torsion, Fournier gangrene (necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum), priapism, paraphimosis, and genitourinary tract trauma. An associated emergent condition is an incarcerated or strangulated inguinal hernia.

• Ultrasound examination is the primary diagnostic tool for differentiation of causes of acute scrotal pain.

• Urology services should be consulted immediately after initial patient evaluation when testicular torsion is suspected.

• Pain out of proportion to the findings on physical examination is the hallmark of early Fournier gangrene.

• In the setting of severe scrotal pain, a necrotic or ischemic cause should be suspected. Testicular torsion, Fournier gangrene, and an incarcerated or strangulated inguinal hernia are surgical emergencies.

• A trial of oral terbutaline, a β-adrenergic agonist, is the least invasive initial treatment of priapism. Corporal blood aspiration with or without irrigation or injection of an α-adrenergic receptor agonist (e.g., phenylephrine) may be necessary if the condition is not reversed rapidly.

• Successful reduction of paraphimosis can often be performed at the bedside without specialty consultation.

• A urologist should be engaged in the care of all but the most minor cases of genitourinary trauma.

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

Priapism is a pathologic condition defined as the presence of a persistent erection lasting longer than 4 hours in the absence of sexual desire or stimulation. It most frequently results from engorgement of the corpora cavernosa with stagnant blood (termed low-flow priapism). Box 111.1 lists several causes of low-flow priapism.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Acute Scrotal Pain

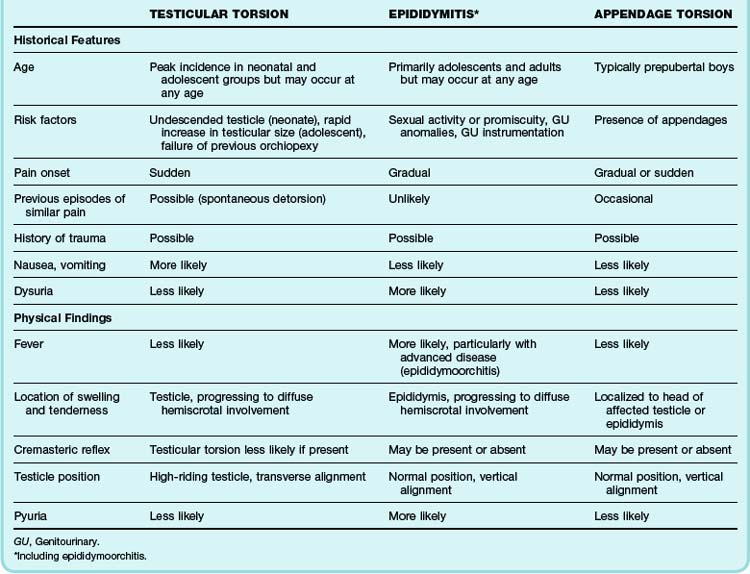

One of the most challenging aspects of male genitourinary complaints is that a wide variety of clinical conditions may all be manifested as acute, unilateral (or bilateral) pain and swelling of the scrotum. Although the differential diagnosis for such symptoms is extensive, threats to life and fertility need to be excluded. Testicular torsion, Fournier gangrene, and an incarcerated or strangulated inguinal hernia are surgical emergencies. The vast majority of acute testicular pain, however, can be attributed to one of three diagnostic entities: testicular torsion, epididymitis, or appendage torsion (Table 111.1).1

Onset of Symptoms

Pain that begins abruptly and is severe suggests testicular torsion.2 Intermittent severe pain can signal intermittent torsion. Twisting of the spermatic cord leads to rapid diminution of blood supply to the affected testicle and resultant ischemic pain. This is in contrast to the more indolent pain of epididymitis, a gradually progressive inflammatory process. Patients with long-standing inguinal hernias often complain of isolated genital pain of prolonged duration. However, patients with an incarcerated (cannot be reduced) or strangulated hernia (with ischemic or infarcted, herniated bowel) may experience more acute pain.

Testicular torsion may accompany a report of minor scrotal trauma.3 Testicular torsion can also take place in the absence of such events and may even occur during sleep.

Associated Symptoms

Patients with nausea or emesis are less likely to have torsion of an appendage or simple, uncomplicated epididymitis. It is more likely that substantial pathology is present. Patients with abdominal pain, nausea, or constitutional symptoms may have testicular torsion, an incarcerated hernia, or another process.2,4,5 Patients with epididymitis may have a low-grade fever, nausea, and malaise; those with advanced infection (e.g., epididymoorchitis) may demonstrate more pronounced constitutional symptoms.6

Physical Examination

Genital Examination

Visual examination of the genitals may reveal cutaneous rashes or lesions, abnormal testicular symmetry or position, edema evident by loss of the scrotal skin folds, and masses. Key visual features of testicular torsion include a high-riding and transverse lie of the affected testicle.2,4,7