Figure 15.1. Overview of the lumbosacral plexus. The origin of the lumbosacral plexus is broader than the brachial plexus in the cervical region. The roots of the lumbar plexus emerge from their foramina within a fascial plane located between the posterior third and anterior two thirds of the psoas muscle. Within the substance of the psoas muscle, the roots form the terminal nerves in a medial to lateral orientation, with the obturator nerve located most medial, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve most lateral, and the femoral nerve in between (15.1B). The terminal nerves are more likely to be blocked by an injection within the substance of the psoas muscles. The lower sacral roots form the sciatic nerve and require a separate injection.

C. The FN is derived from the dorsal divisions of the anterior rami of the L2-4 spinal nerve roots.

1. The FN emerges from the lateral border of the lower part of the psoas muscle within a musculoskeletal fascial compartment between the psoas and iliacus muscles deep to the fascia iliaca. It descends inferiorly and enters the thigh deep to the inguinal ligament. At the level of the inguinal ligament, the FN lies 1 to 2 cm lateral and posterior to the femoral artery (FA).

2. As the FN descends a few centimeters caudad to the inguinal ligament, which is often at the level of the inguinal crease (IC), the FN consistently lays directly lateral to the pulsatile FA. At either location, the FN is located deep to the investing fascia of the iliacus muscle, the fascia iliaca, which is the key anatomic component for successful block of the FN. The fascia iliaca encloses the FN within the fascial compartment and separates it from the femoral sheath, which contains both the FA and femoral vein (FV) in a separate fascial compartment from the FN. The fascia iliaca thickens as it courses medially to become the iliopectineal ligament, which anatomically separates the FN from the FA and femoral vein residing in the femoral sheath compartment medial to the nerve (4).

3. As the FN courses inferiorly into the thigh, it divides into anterior and posterior divisions that arborize to become terminal branches of the FN. The anterior division of the FN supplies the cutaneous innervation to the anterior and medial surfaces of the thigh through the medial and intermediate cutaneous nerves. The muscular branches of the anterior division innervate the sartorius and pectineus muscles, besides providing articular branches to the hip joint. The posterior division supplies the muscular innervation to the quadriceps femoris muscles, articular branches to the knee joint, and the anterior portion of the femur.

4. The terminal fibers of the posterior branch constitute the saphenous nerve (SN), which descends inferiorly in the medial aspect of the thigh within the adductor canal. At the distal part of the medial thigh, the SN emerges from the adductor canal deep to the sartorius muscle (SM) and then continues further distally to supply the cutaneous innervation to the anteromedial lower leg and medial aspect of the foot. The SN also provides articular innervation to the medial aspects of the knee and ankle joints.

D. The LFCN is derived from the posterior divisions of the anterior rami of the L2-3 spinal nerve roots. It emerges from the lateral border of the psoas major muscle at the level of the inferior margin of L4. It courses obliquely around the iliac fossa toward the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) on the surface of the iliacus muscle within the fascia iliaca compartment. The LFCN then descends toward the thigh passing deep to the inguinal ligament approximately 1 to 2 cm medial to ASIS dividing into anterior and posterior branches. It may also pass under the inguinal ligament as much as 7 cm medial to the ASIS or directly through the SM. The LFCN supplies the skin over widely variable distribution of the lateral and anterior thigh as far distally as the knee. It has no motor innervation (4).

E. The obturator nerve is derived from the anterior divisions of the anterior rami of L2-4 spinal nerve roots. It is a mixed nerve supplying the motor innervation to the adductor compartment of the thigh and articular branches to both the hip and knee joints. Additionally, the obturator nerve supplies a variable cutaneous distribution to the posterior-medial portion of the distal thigh, which may be absent in up to 50% of subjects (5).

1. The obturator nerve emerges from the medial border of the psoas muscle and descends along the sidewall of the pelvis close to the inferior-lateral portion of the bladder wall until it enters the adductor compartment of the medial thigh by passing through the obturator foramen. Shortly after leaving the obturator foramen, the obturator nerve divides into anterior and posterior division.

2. The anterior division descends deep to the adductor longus (AL) and pectineus muscles and superficial to the adductor brevis (AB) and obturator externus (5–7). It provides muscular branches to the superficial adductor muscles (AL, AB, and gracilis) and articular branches to the anterior-medial aspect of the hip joint. Also, it inconsistently provides a cutaneous branch to the posterior-medial portion of the distal thigh.

3. The posterior division descends deep to the AB and superficial to the adductor magnus (AM), just slightly lateral to anterior division in the parasagittal plane (5–7). The posterior division descends with the FA within the adductor canal and terminates by exiting the adductor hiatus to enter the popliteal fossa. The posterior division supplies muscular branches to the AM and obturator externus, as well as an articular branch to the posterior aspect of the knee joint (5).

III. Indications

A. Lumbar plexus block through the psoas compartment approach in conjunction with sciatic nerve block can provide surgical anesthesia for the entire lower extremity, excluding the hip joint. For surgical anesthesia of the hip joint, a psoas compartment block (femoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, and obturator nerves) must be combined with a sacral plexus block that not only blocks the sciatic nerve but also the nerve to the quadratus femoris and superior gluteal nerve, which are branches that come off the sacral plexus proximal to classic gluteal approaches to a sciatic nerve block. A lumbar plexus or FN block alone will provide surgical anesthesia for procedures of the superficial anterior thigh. The most common indication for a psoas compartment block is to provide postoperative analgesia for major hip surgery. Typically, a single-injection technique will provide sufficient postoperative analgesia for a primary hip arthroplasty, but a hip arthroplasty revision may benefit from the extended analgesia provided by a continuous psoas compartment catheter.

B. An FN block is the most commonly performed block of the lower extremity. A single-injection FN block will provide surgical anesthesia for superficial procedures of the anterior thigh, and with the use of a long-acting local anesthetic (LA), it will provide postoperative analgesia for surgical procedures of the femur and knee joint. The most common indication for either a single-injection or continuous FN block is for postoperative analgesia after major knee surgeries such as total knee arthroplasty (TKA) or anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

C. LFCN block alone may be used to provide anesthesia for cutaneous procedures of the lateral aspect of the thigh. More commonly, it has been used as a diagnostic nerve block to confirm the diagnosis of neuralgia of the LFCN, more commonly known as meralgia paresthetica.

D. Obturator nerve block (ONB) is commonly used to treat adductor muscle spasm associated with neurologic disorders such as strokes, multiple sclerosis, or cerebral palsy. ONB is also occasionally indicated to suppress the obturator reflex associated with transurethral resection of the lateral bladder wall. Activation of the obturator reflex may result in sudden violent adduction of the ipsilateral thigh, which not only interferes with the surgical procedure but may also increase the risk of bladder wall perforation or vessel laceration by the resectoscope. Additionally, ONB has been demonstrated to provide a decrease in opioid consumption and pain in patients undergoing TKA when added to sciatic and FN blocks.

E. An SN block may be used in conjunction with distal sciatic nerve block to provide complete anesthesia of the lower leg. The advantage of this approach is surgical anesthesia of the lower leg, ankle, and foot without blocking either the hamstrings (with a more proximal sciatic nerve block) or the quadriceps (with FN block).

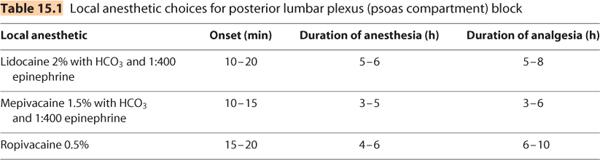

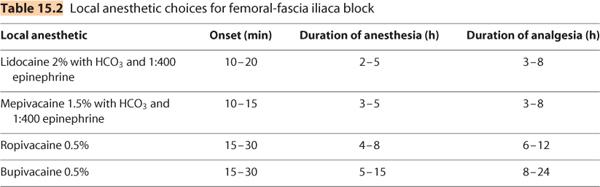

IV. Choice of local anesthetic

The choice of LA for the major lumbar plexus blocks (psoas compartment and femoral-fascia iliaca) is dependent on the requirements for onset of anesthesia and duration of analgesia for single-injection techniques. With the advent of continuous peripheral perineural catheter techniques, the anesthesiologist has the advantage of providing a rapid onset of surgical block by injection of the shorter-acting LAs (Table 15.1) through the needle or catheter tip (the primary anesthetic block). Subsequently, an infusion of a dilute LA that possesses sensory motor dissociation (the most commonly used being ropivacaine 0.2% or bupivacaine 0.125%) (Table 15.2) may be used to provide the optimal balance of postoperative analgesia with less motor block to facilitate postoperative rehabilitation and recovery. Alternatively, if a central neuraxial technique is chosen as the primary anesthetic, a loading dose (10–15 mL) of the analgesic infusion of ropivacaine 0.2% may be started intraoperatively. The typical postoperative regimen consists of running the analgesic infusion at 4 to 8 mL/h with or without a patient-controlled bolus of 2 to 3 mL every 20 minutes.

V. Techniques

The most common techniques for anesthetizing the lumbar plexus and its individual branches are described in the subsequent text. Peripheral nerve stimulator techniques that focus on surface landmarks and evoked motor responses (EMRs), as well as ultrasound (US)-guided techniques (when available) will be discussed. Additionally, both single-injection and continuous peripheral perineural catheter techniques will be described. Paresthesia techniques are not commonly used for lower extremity nerve blocks.

A. Posterior lumbar plexus (psoas compartment) block. The lumbar plexus is most commonly located (and blocked) within the substance of the psoas major muscle and at the junction of the posterior third and anterior two thirds of the muscle (1–3). The lumbar plexus is consistently located within 2 to 3 cm anterior to the transverse process of the lumbar vertebrae (8–10). Knowledge of these anatomic considerations allows for increased success and decreased potential risk of serious complications. Because this approach is close to the central neuraxial space, it is recommended that patient preparation include standard monitoring (continuous pulse oximetry, electrocardiogram, and intermittent noninvasive blood pressure). Additionally, medications and airway management equipment for emergency resuscitation should be immediately available. The technique of Capdevila et al. using a peripheral nerve stimulator is described (8–10).

1. Patient position. The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with a slight forward tilt, hips flexed with the operative side to be blocked uppermost.

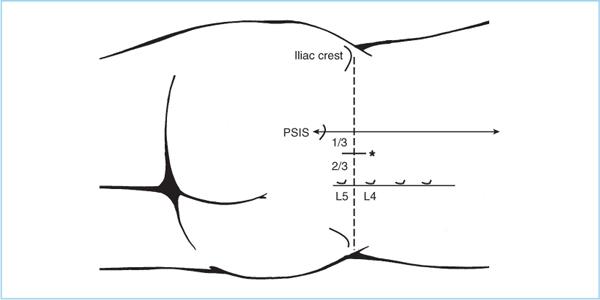

2. External landmarks. The iliac crests and the spinous process of the fourth lumbar vertebrae (L4) are identified. A line is drawn connecting the iliac crests (intercristal line). A second line is drawn through the center of the L4 spinous process perpendicular to the intercristal line. A third line is drawn parallel to the second line (representing the spinal column) through the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). The needle insertion point is located along the intercristal line at the junction of the lateral third and medial thirds of the second line (representing the center of the spinal column) and third line (representing the center of the PSIS) (Figure 15.2).

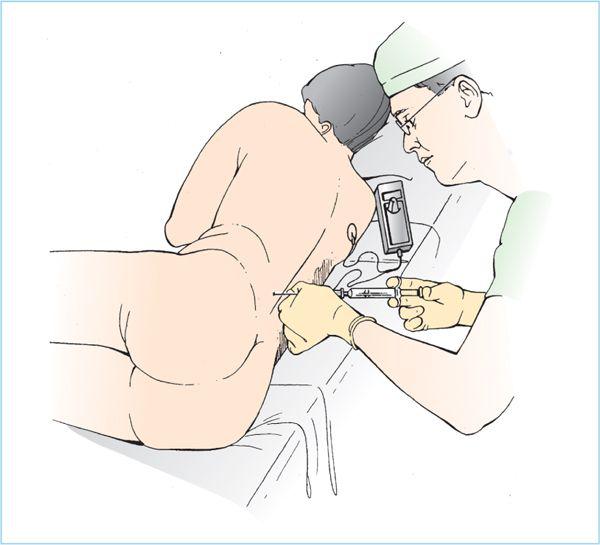

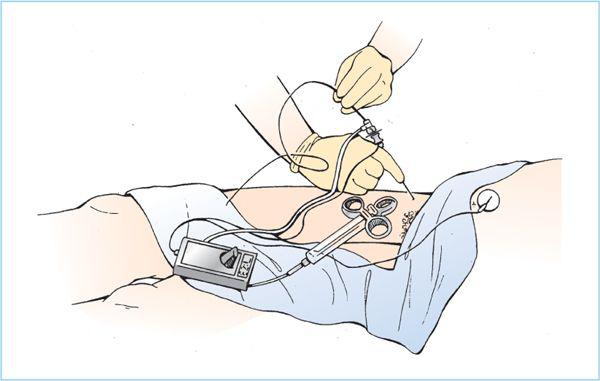

3. After aseptic skin preparation and draping followed by LA infiltration of the proposed needle insertion point, a stimulating needle (typically 100–150 mm [4–6 in.], 20–21 gauge) is slowly advanced at right angles to the coronal plane of the body (Figure 15.3). The stimulating needle is attached to a peripheral nerve stimulator (typical settings of 1.5–2.0 mA, 2 Hz, 100 μs) and to a syringe of LA.

Figure 15.2. Skin landmarks for psoas compartment block. (Reproduced from Capdevila X, Macaire P, Dadure C, et al. Continuous psoas compartment block for postoperative analgesia after total hip arthroplasty: new landmarks, technical guidelines, and clinical evaluation. Anesth Analg 2002;94:1606–1613.)

Figure 15.3. Psoas compartment block. A 4-in. needle is advanced perpendicular to the skin until a loss of resistance (similar to an epidural injection) is obtained. At this point, compartment entry can be confirmed by eliciting a response to a nerve stimulator. A catheter can be inserted if continuous analgesia is desired.

4. The goal is to advance the needle until contact with lumbar transverse process (presumably L4) is made. The rationale for attempting to locate the transverse process is as follows. The distance from the skin to the lumbar plexus is typically 60 to 100 mm depending on gender and body mass index (BMI). In contrast, the distance from the transverse process to the lumbar plexus ranges between 15 and 20 mm with a median value of 18 mm, regardless of gender or BMI.

5. After contact with the transverse process is made, the needle is withdrawn 0.2 cm and redirected under the transverse process and advanced until the desired EMR is elicited. The desired EMR is quadriceps muscle contractions (QMCs) and the position of the stimulating needle (or catheter) tip is judged to be adequate when the current output is 0.5 to 1.0 mA. If the QMC is not elicited after advancing the needle 20 to 30 mm past the transverse process, the needle is withdrawn and redirected in 15-degree increments in a medial-to-lateral plane (perpendicular to cephalad-caudad course of the FN within the psoas muscle) until QMCs are elicited.

6. After optimizing the stimulating needle tip position, aspiration and a 3-mL test dose are performed to confirm the absence of either an intravascular or central neuraxial location of the LA injection. Typically, 25 to 35 mL of LA is incrementally injected with frequent aspirations to reduce the potential risk of intravascular injection. A typical onset time for anesthesia is 15 to 30 minutes depending on the type and total mass of LA injected.

7. A continuous catheter technique may be utilized to provide extended duration analgesia. The approach is exactly the same as for the single-injection technique except for the following. A larger bore (17- to 18-gauge) insulated stimulating Tuohy needle is typically used to localize the lumbar plexus. After localization of the lumbar plexus with the single-injection technique, a 19- to 20-gauge catheter is inserted through the Tuohy needle and advanced no more than 2 cm past the needle tip. The needle is then withdrawn over the catheter and fixed in place with a sterile clear adhesive dressing. The proximal end of the catheter is then connected to an automated infusion pump.

8. Clinical pearls

a. Contact with the transverse process is a key safety step. Advancing the needle tip more than 20 to 30 mm deep to the transverse process significantly increases the potential for retroperitoneal injection.

b. The correct EMR must be obtained. Stimulation of the obturator nerve will result in an EMR of the adductor muscles and should not be accepted for two reasons: (i) The obturator nerve may be in a separate muscle-fascial plane from the FN and LFCN (1, 2), and (ii) the obturator nerve EMR places the needle tip more medially within the psoas muscle. The distance between the internal border of psoas muscle and the median sagittal plane is only 2.7 ± 0.6 cm (2). Therefore, medial placement of the needle tip may increase the potential risk of unintended central neuraxial anesthesia. Elicitation of sacral EMR (such as hamstring contractions, dorsiflexion, or plantarflexion at the ankle) indicates that the needle tip is too caudal at the level of the lumbosacral trunk, potentially resulting in a failed or incomplete block of the lumbar plexus.

B. Anterior lumbar plexus block. The FN may be blocked by a variety of methods. A paravascular approach several centimeters caudad to the inguinal ligament using a peripheral nerve stimulator technique is still the most commonly used technique. An US-guided approach directly visualizing the paravascular location of the FN (typically just lateral to the FA) deep to the fascia iliaca is gaining increased popularity. Lastly, the fascia iliaca approach simply relies on appreciating the “loss of resistance” or “double-pop” sensation when a blunt needle is passed through the fascia lata and then the fascia iliaca. Despite the seemingly different approaches of these three techniques, they all share one common key anatomic component. The FN is always located deep to fascia iliaca in a separate fascial compartment from the FA and vein (which are located within the femoral sheath, but superficial to the fascia iliaca).

Figure 15.4. Femoral nerve block, nerve stimulator. The needle is introduced lateral to the artery and a motor response or a paresthesia is sought. If a large needle is used, a continuous catheter can be inserted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree