Chapter 29 Lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is defined as bleeding within the GI tract, originating distal to the ligament of Treitz. The majority of lower GI bleeding is self-limited and does not require intervention. However, patients in a critical care unit frequently have comorbidities, particularly coagulopathy,1 that can make the management of lower GI bleeding more challenging and urgent. The patient with poor cardiopulmonary reserve is more prone to develop complications such as coronary ischemia and its sequelae from the hemorrhage and its resulting state of hypo-perfusion. Knowledge about the clinical presentation and diagnostic techniques as well therapeutic options as discussed in this chapter will prompt early diagnosis and management of the disorders and hopefully prevent these complications which could prolong intensive care unit (ICU) care and increase the incidence of further complications such as respiratory and hemodynamic compromise in the ICU patient. This chapter will focus on the pathophysiology and current management of moderate to severe lower GI bleeding with an emphasis on the causes of lower GI bleeding that are more common in critical care patients. Table. 1. Lower gastrointestinal causes of bleeding.

Lower Gastrointestinal (GI) Hemorrhage

Jonathan Hong and Marcus Burnstein

Introduction and Chapter Overview

Diverticular disease |

Ateriovenous malformation/Angiodysplasia |

Ischemic colitis |

Benign anorectal conditions e.g., Hemorrhoids, anal fissure |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

Neoplasia |

Infectious colitis e.g., Clostridium difficle |

Coagulopathy |

Small bowel e.g., Meckels diverticulum, carcinoid, Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST), adenocarcinoma |

Epidemiology

The estimated annual incidence of lower GI bleeding is 20–30 per 100,000 persons but there is a range of severity from occult blood in the stool to life-threatening lower GI bleeding.2 The majority of lower GI bleeding is self-limited and requires only close observation, supportive treatment, and outpatient investigation. Massive lower GI bleeding is arbitrarily defined as bleeding associated with a systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg, and/or a hematocrit drop of greater than 20%, and/or a need for more than two units of packed red cells in a 24-hour period. The possible causes are listed in Table 1.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Features

Diverticular disease

Diverticular disease is estimated to have an incidence of 65% by age 85. Diverticula can be found throughout the colon but are more common in the sigmoid colon. Interestingly, bleeding originating from diverticula often originates from the right side of the colon.3 Bleeding diverticula are thought to be the cause of lower GI bleeding in approximately 30% of cases.4

The vast majority of colonic diverticula are false or pseudodiverticula, the wall of the diverticula consisting only of the mucosal layer. Mucosal outpouchings form at weak points where the circular muscle of the colonic wall is penetrated by blood vessels (vasa recta). The pathophysiology of colonic diverticulosis is disputed but the geographical distribution implicates a Western low fiber diet resulting in high intra-colonic colonic pressures and “pulsion” diverticula. Others have suggested that a connective tissue disorder may play a role. The increasing prevalence with increasing age suggests that this is also a risk factor.

The vasa recta are separated from the bowel lumen only by the diverticular mucosa and it is thought that recurrent injury leads to thinning of the media of the vessel, predisposing to rupture.

Approximately 17% of patients with diverticulosis with develop significant bleeding. Typically these episodes are not associated with pain. The majority of diverticular bleeding stops spontaneously but in up to 20% of cases the bleeding is more severe and requires intervention.5

Ischemic colitis

This condition results when blood flow is inadequate to meet the tissue demands for oxygen, which results in injury to the colon. The severity ranges from a reversible, transient mild colitis to colonic infarction.

The colon is particularly susceptible to ischemia as it receives less blood flow than the rest of the GI tract and the microvascular plexus of the colon is less well developed than in the small bowel.6 As a result, colonic blood flow is strongly affected by mesenteric vasoconstriction.

Both ischemia and reperfusion play a role in injury to the colon. The earliest changes are seen in the mucosa, which eventually sloughs, resulting in ulceration. As hypo-perfusion resolves, the ulcerated areas can bleed.

The splenic flexure is the most vulnerable segment of colon due to its “watershed” anatomy, but the sigmoid and right colon may also be affected. About 2–3% of patients undergoing aortic repair will develop clinically significant ischemic colitis.6

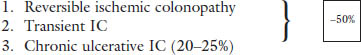

The spectrum of ischemic colitis (IC) has been classified into the following types.7

4. Ischemic colon stricture (10–15%)

5. Colonic gangrene (15%)

6. Fulminant universal (1%)

This condition is particularly relevant in the critical care setting where hypotension, hemorrhage, or shock can precipitate an event and where coagulopathy can result in severe bleeding. Furthermore, the use of vasopressors can exacerbate low-flow states and contribute to mesenteric shunting, which may contribute to colonic ischemia.

In the non-intubated and awake patient the typical symptoms are left sided abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. However, in intubated and sedated patients, bleeding may be the only feature. Laboratory tests, such lactate, are not reliable for diagnosis. A Computed Tomography (CT) scan enhanced with arterial phase intravenous contrast is a very useful modality to identify colitis and exclude arterial occlusion. The CT findings suggestive of colitis are bowel wall thickening and pericolonic stranding. Edema in the submucosa, which may occur after reperfusion, may result in a double halo sign.

Angiodysplasia

Angiodyplasia are acquired, vascular lesions found in the mucosa and submucosa. They are comprised of thin walled vessels, which are more common in the right colon and thought to be associated with aging. There is an association with aortic stenosis (Heyde syndrome), and lesions have been reported to resolve following valve replacement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree