CHAPTER 65 LOWER EXTREMITY VASCULAR INJURIES: FEMORAL, POPLITEAL, AND SHANK VESSEL INJURY

Lower extremity vascular injuries can be devastating and life threatening. The morbidity and mortality associated with these injuries are dependent on a multitude of factors, including the extent of injury, overall condition of the patient, and duration of ischemia. Deciding whether limb salvage is the optimal management for the injured patient requires good judgment. The initial decision to salvage the injured extremity depends on the ability of the patient to tolerate the procedure required to successfully repair the injury. It also depends on the likelihood of limb salvage as well as a satisfactory functional limb outcome. In the past, ligation of vascular injuries was often the approach taken to “save a life,” and was favored because of a high amputation rate (up to 40%) reported when a surgical approach to repair the injuries was used.1 Currently, the amputation rate in civilian trauma undergoing vascular repair is below 10% and this is not the preferred approach to manage extremity vascular injury. This reduction in the amputation rate over the past few decades has been attributed to a multitude of factors, including rapid transport time, improved prehospital care, soft tissue coverage, decreasing warm ischemia time (using the damage control approach and vascular shunt), low-velocity weapons, antibiotic utilization, and the early and aggressive use of fasciotomy.

INCIDENCE AND MECHANISM OF INJURY

Lower extremity vascular injuries occur most frequently in young men. In both the urban and rural setting, penetrating injuries to the extremity are the most common cause of peripheral vascular trauma. Penetrating injuries occur more commonly in the urban setting because of high levels of interpersonal violence and mostly result from gunshot wounds or stab wounds.1 Blunt injuries occur more commonly in the rural setting because of a higher incidence of farming and industrial-type injuries. In part caused by a rise in urban violence and high-speed motor vehicles, the incidence of peripheral vascular trauma is increasing. Compared with other arterial injury, such as in the neck and chest, which may be rapidly fatal, most isolated peripheral vascular injuries are not immediately fatal and patients usually survive transportation to a medical center.2 Extremity vascular injury accounts for up to 50% of all arterial injuries seen at civilian trauma centers. Although the exact incidence of peripheral vascular injuries is variable, upper and lower extremity vascular trauma has a similar incidence in an urban setting. Within the lower extremity, femoral arterial injuries are more common than popliteal injuries and account for up to 70% of all lower vascular injuries treated in urban trauma centers.4–15

DIAGNOSIS

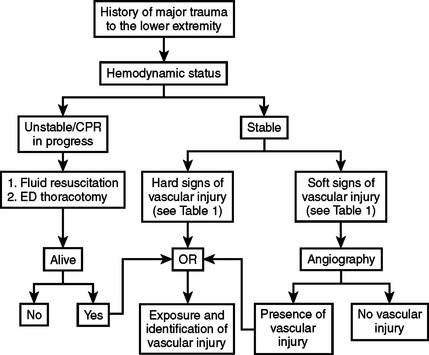

The diagnosis of peripheral vascular trauma can usually be made based on a quick history and physical examination of the extremity, including a systematic and thorough neurovascular evaluation (Figure 1). There are a multitude of signs of vascular injury on examination. They are divided into hard and soft signs and reflect the likelihood that a significant vascular injury is present. Hard signs (Table 1) indicate a high likelihood that a significant vascular injury is present. Thus, patients with hard signs should be taken directly to the operating room to undergo immediate operative management.2 Patients with soft signs of vascular injury (see Table 1) are less likely to have a significant vascular injury. This, however, must be confirmed using more invasive diagnostic modalities. Arteriography is currently the best available modality for the diagnosis of vascular injury in stable patients with soft signs of vascular injury but without evidence of peripheral ischemia. It can also be used in selected cases where the exact location of the injury is difficult to determine (e.g., pellet wounds or multiple gunshot wounds) and where the optimal incision and approach cannot be determined a priori. Arteriography can be performed in the angiography suite by an interventional radiologist or intraoperatively by the surgeon. It can be time consuming, but it is both sensitive and specific in the diagnosis of extremity vascular injury. Spiral computed tomographic angiography (CT-A) with the newest generation of high-speed scanner is an alternative diagnostic modality that has not yet been fully evaluated or widely accepted. It is rapid and does not require arterial catheterization. It does require contrast infusion, has no therapeutic potential, and can be limited by the artifacts generated if foreign bodies are present in the extremity.2

Table 1 Signs of Vascular Injuries

| Hard Signs |

| Soft Signs |

The types of arterial trauma that have been described include laceration, transaction (complete or partial), contusion (with or without thrombosis), aneurysm (true or false), arteriovenous (AV) fistula, intimal disruption, and external compression by a hematoma. Lacerations and transections account for the great majority of arterial trauma.1

OPERATIVE MANAGEMENT FOR ALL PERIPHERAL VASCULAR INJURY

Preoperative Management

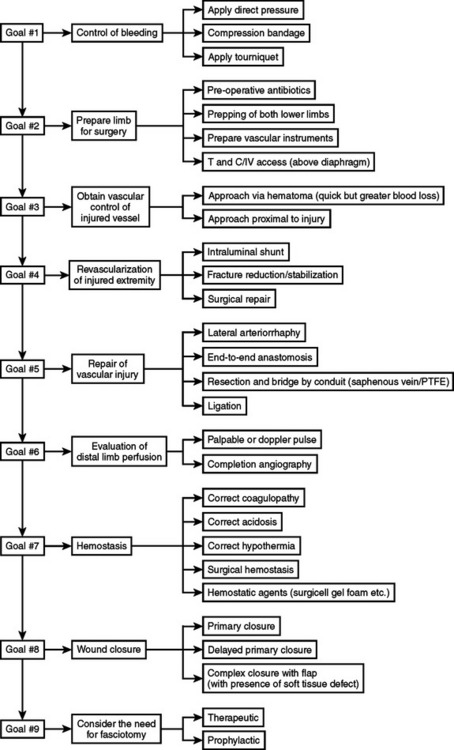

The initial objective in the management of peripheral vascular injury is to control bleeding to avoid exsanguination. This can immediately be accomplished using digital pressure, compressive bandages, or a tourniquet. Simultaneously, adequate fluid resuscitation is essential to limit the duration and extent of shock. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should also be administered in a timely fashion. Both groins, the lower abdomen, and both lower extremities should be prepped and draped. Prepping and draping the entire injured extremity including the distal aspect is important to assess for distal perfusion, assess the development of compartment syndrome, and perform fasciotomies if required. Prepping and draping the uninjured extremity allows for the harvesting of the greater saphenous vein if required to provide for a suitable replacement conduit. Vascular clamps, vessel loops, and fine monofilament sutures must be available before surgery begins.

Intraoperative Management

Controlling active bleeding before the start of the operation allows for sufficient time to obtain proximal and distal vascular control without further blood loss and prevents contamination of the surgical field by further bleeding. Approaching the hematoma directly may be useful in selected cases, but good judgment is required, as this can result in significant and potentially needless blood loss, which can further compromise the patient’s hemodynamic and metabolic status, leading to a poor outcome. The cornerstone principle is to obtain proximal and distal control rapidly along with revascularization of the injured extremity. Surgical repair and temporary shunting are the main two options. The use of intraluminal shunt is advisable in patients who cannot tolerate surgical repair because of extreme systemic abnormalities such as acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy. Also, when fracture stabilization may compromise the vascular repair, shunting should be performed before definitive vascular repair (Figure 2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree