188 Local and Regional Anesthesia

• Alternatives to local infiltration for anesthesia include topical anesthesia and regional nerve blocks.

• Comfortable wound repair requires adequate anesthesia.

• Local infiltration may be inadequate or suboptimal in certain situations.

• For the safety and efficacy of regional anesthesia, the clinician must have a detailed understanding of the local anatomy.

• Ultrasound is a very useful adjunct to regional anesthesia.

Selection of Anesthetic Agents

Mechanism of Action

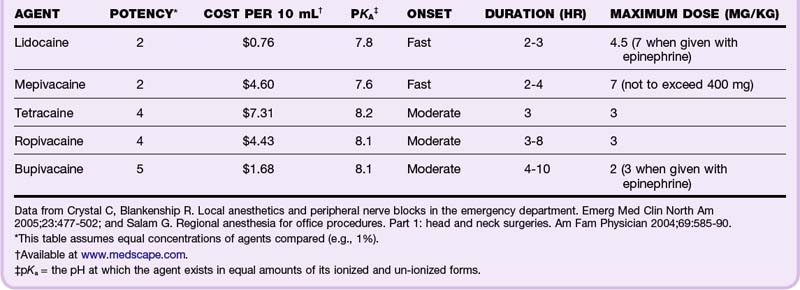

Local anesthetics usually have an aromatic ring structure connected to a tertiary amine by either an ester or an amide link. This link determines the class of the agent, ester or amide. Local anesthetics work by reversibly binding to and blocking neuronal sodium channels, thereby blocking conduction of the nerve impulse. Their potency, onset, and duration of action are determined by their ability to access and bind these sodium channels. The higher the lipid solubility, the higher the potency of the anesthetic. The higher their protein binding, the longer the duration of action. Onset of action is determined by the pKa, or the pH at which the agent exists in equal amounts of its ionized and un-ionized forms. The closer the pKa is to physiologic pH, the faster the onset of action.1 Most local anesthetic agents are associated with a burning sensation that lasts several seconds before the onset of anesthesia. Patients should be warned of this sensation before administration (Table 188.1).

Toxicity

An intercostal block has the highest potential for toxicity; therefore, the maximum amount of anesthetic agent recommended for this location is only one tenth of the maximum for peripheral nerve blocks.1 All sites are associated with a certain degree of risk, especially when accidental intravascular injection is likely.

Signs of CNS toxicity with local anesthetics are presented in Box 188.1.

If exposure is not halted, toxicity can progress to seizures, coma, respiratory depression, and cardiorespiratory arrest. Higher doses result in cardiovascular toxicity and lead to tachycardias, sinus arrest, atrioventricular dissociation, hypotension, and full arrest. Premedication with benzodiazepines may blunt the CNS toxicity, and in these cases the first sign of toxicity to develop may be cardiovascular collapse.2,3 Amides are metabolized by the liver, and patients with hepatic dysfunction may be predisposed to systemic toxicity. Esters are metabolized by plasma pseudocholinesterase, and therefore patients with pseudocholinesterase deficiency, such as those with myasthenia gravis, are at higher risk for systemic toxicity. In addition, metabolites of prilocaine (a component of EMLA cream) and benzocaine have been associated with methemoglobinemia.

Systemic Agents

Lidocaine

Lidocaine is the most commonly used local anesthetic agent. Its low cost, rapid onset, duration, and toxicity profile make it ideal for most routine applications. The maximum dose of lidocaine is 4 to 4.5 mg/kg (e.g., a 70-kg patient should receive no more than 300 mg, or 30 mL of a 1% solution). The maximum dose may be increased to 7 mg/kg when lidocaine is given with epinephrine but will also cause an increase in sympathomimetic side effects (tachycardia and hypertension) and a theoretically higher risk for infection because of diminished blood supply to the affected area. The pain of injection can be reduced either by warming lidocaine to body temperature before administration4 or by buffering it with sodium bicarbonate (1 mL sodium bicarbonate to 9 mL of 1% lidocaine).2,5

Allergic Reactions

True allergic reactions to local anesthetics are relatively rare. They are usually secondary to the preservative rather than to the agent itself. If an allergy is reported but not verified, the emergency physician should consider using a preservative-free agent, such as cardiac lidocaine from the “code” cart. Other options include switching classes (allergy to esters is more common than allergy to amides, and cross-reactivity is common within the class) or using benzyl alcohol,6 diphenhydramine,7 ice, or normal saline injection. An easy way to determine the class of an agent is to remember that all amides have two i’s in their names and the esters only have one. If a patient is truly allergic to lidocaine, none of the anesthetic agents with two i’s should be used (diphenhydramine is an exception to this rule of thumb because it is not classically considered an anesthetic agent).

Topical Agents

Lidocaine, Epinephrine, and Tetracaine

LET (lidocaine 4%, epinephrine 0.1%, tetracaine 0.5%) is an excellent and safe topical anesthetic agent. It can be premixed by the hospital pharmacy and stored in the refrigerator for use in the ED. It is applied to wounds by soaking a cotton ball in LET and then securing the cotton ball to the wound for 15 to 30 minutes. Blanching of the skin around the wound indicates adequate anesthesia. Additional injected anesthetic may be required, but its application should be much more comfortable for the patient after LET pretreatment. LET (or any mixture containing epinephrine) should, by convention, not be used on the ear, nose, penis, or digits because of its vasoconstrictor effects.8,9

EMLA

EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics: 2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine) is approved by the FDA only for use on intact skin, although successful use in open wounds has been reported in the medical literature. Approximately 1 hour of topical application of EMLA is required to achieve local anesthesia, a characteristic that limits its usefulness in emergency cases. Infants younger than 3 months are at theoretically higher risk for the development of methemoglobinemia from EMLA because of inadequate levels of methemoglobin reductase.1,8,9

Liposomal Lidocaine

ELA-Max is a relatively new proprietary mixture of 4% liposomal lidocaine that has been approved by the FDA for the temporary relief of pain from minor cuts and abrasions. Its onset of action is much shorter than that of EMLA (only 30 minutes), and it carries a much lower risk for methemoglobinemia because it does not contain prilocaine. This formulation may replace EMLA for most topical indications.8,9

Regional Nerve Blocks

General Technique

1. Prepare the skin with povidone-iodine or other antiseptic skin solution.

2. Identify the area’s landmarks.

3. Induce a superficial skin wheal at the injection site to reduce the discomfort of further manipulation.

4. Advance the needle to the target area while asking the patient to report any paresthesias.

5. If the patient does report paresthesias, thus indicating that the needle is within the nerve sheath, withdraw the needle 1 to 2 mm, aspirate to ensure that the needle is not in a vessel, and inject the agent slowly.