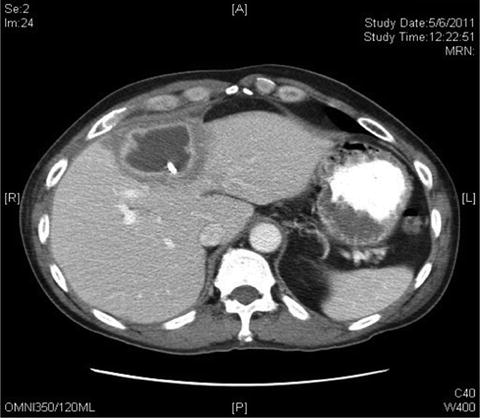

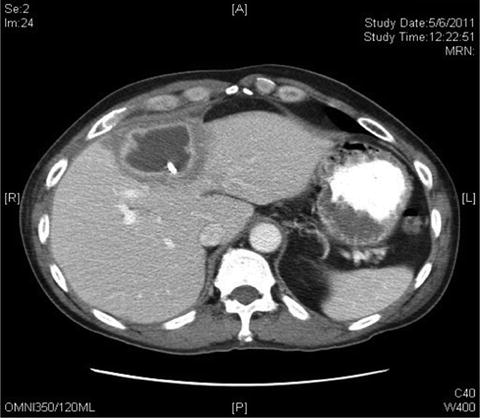

Fig. 22.1

A 52-year-old Mexican male who presented with RUQ pain and jaundice with pyogenic abscess

Treatment

The initial treatment of any patient suspected of having a possible liver abscess is initiation of broad spectrum antibiotics. The development of broad spectrum single agents (imipenim, piperacillen/tazobactam) has replaced the traditional treatment of the combination of ampicillin, aminoglycoside, and an anaerobic drug such as metronidazole [7]. The duration of antibiotic use remains debatable, and is usually based on treatment response and the abscess characteristics.

Percutaneous drainage was first reported in 1953 but did not become accepted as standard therapy until the 1980s. It has now become the treatment of choice for pyogenic hepatic abscesses. It is usually performed either with ultrasound or CT guidance, and success rates range from approximately 60–90%. There is still some debate, however, as to percutaneous aspiration alone versus catheter drainage. Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of percutaneous aspiration alone. Giorgio et al. reviewed 39 patients with hepatic abscesses who were treated with aspiration alone; 36 of the 39 (92.3%) were successfully treated with a single aspiration, and the other three patients only required one more aspiration. There were no deaths or complications in his study [8]. Yu et al. demonstrated a 96.8% success rate in 64 patients with aspiration alone; approximately half (49.5%) required a single aspiration and the rest of the patients required multiple aspirations. In his study, two patients died of overwhelming sepsis and another required surgical intervention for a liver laceration. However, other studies have demonstrated superiority of catheter drainage [9]. Rajak et al. randomly assigned 50 patients to aspiration or catheter drainage. Residual abscess after two aspirations was considered failure in the aspiration group, and residual abscess after catheter drainage was considered failure in the catheter group. Only 60% responded to the needle aspiration, whereas 100% responded in the catheter drainage group [10]. Zerem et al. prospectively randomized patients to percutaneous aspiration versus catheter drainage. Similar to the last study, percutaneous aspiration was successful in 67% of patients, whereas catheter drainage was successful 100% of the time [11].

Catheter drainage appears to also be successful in patients with multiloculated or multiple abscesses. A series by Liu et al. found no difference between single and multiple abscesses and had very high clinical success rates of treatment of 87% for a single abscess and 92% for multiple abscesses with catheter drainage. That study also found an 88% success rate for treatment of a single multiloculated abscess as well as a 90% success rate for multiple multiloculated abscesses [12]. Failure of catheter drainage appears to be decreasing but still exists in approximately 10% of patients. A recent case series by Mezhir et al. demonstrated only a 66% success with catheter drainage; however, in this study, 88% of patients had a history of gastrointestinal malignancy. Nine percent of these patients required surgical intervention, whereas the rest of the patients who failed percutaneous drainage died with indwelling catheters. Independent predictors of failure of catheter drainage included positive yeast cultures and communication with the biliary tree [7].

Surgical therapy is rarely necessary as the first line of intervention. If necessary, it is usually in patients with an obstructed biliary system than is not amenable to nonsurgical decompression or a ruptured abscess with sepsis. More commonly, surgical intervention is now reserved only when percutaneous drainage has failed, the abscess is not amenable to percutaneous drainage (multiloculated or large), or when there is a complication from percutaneous drainage [6].

Surgical Therapy

If the cause of the hepatic abscess is unknown, a careful exploration of the abdomen should be performed to rule out any other abdominal pathology. Surgical drainage of the abscess is then performed by localization of the abscess via ultrasound or needle localization with ultrasound guidance. The abscess is then bluntly opened and the pus evacuated. Blunt finger manipulation can be used to break up loculations and adhesions. Careful hemostasis should be obtained to prevent residual fluid collections or recurrent abscess. Large bore drains are then left in place for irrigation and suction of the abscess cavity. Tan et al. retrospectively reviewed 80 patients with pyogenic abscesses >5 cm who were treated either with surgical drainage (44 patients) or percutaneous drainage (36 patients). Eighty percent of these patients had multiloculated abscesses. In this study, the surgical drainage group had less treatment failure, less secondary procedures, and a shorter length of stay. The mortality for the surgical drainage group was 4.5% and 2.8% for the percutaneous group, which was not statistically significant [13].

Some case reports have advocated primary liver resection for hepatic abscess. Hope et al. retrospectively reviewed patients with >3 cm multiloculated pyogenic abscess who were treated with percutaneous drainage along with antibiotics versus treatment with partial liver resections. The resection group had a 100% success rate of treatment and 7.4% mortality in this group, whereas the drainage group only had a 33% success rate for treatment and 4.7% mortality. Eight patients in the latter group required repeat drainage and five required surgical resection. The mortality rates between the two groups also did not reach statistical significance. The authors concluded that for large multiloculated abscesses, surgical treatment may be the primary mode of treatment of the disease [14]. Strong et al. reviewed 49 patients who underwent resection for hepatic abscesses after either failed conservative treatment or underlying hepatobiliary pathology. All of the patients had resolution of their abscesses and no patients required reoperation. The authors did report 4% mortality in their group after abscess rupture in two patients [15].

Conclusion

Pyogenic abscesses are bacterial in origin and more likely to be associated with a hepatobiliary pathology. Primary treatment is broad spectrum antibiotics along with percutaneous treatment via aspiration or catheter drainage. Rarely, a patient may need surgical therapy for failed percutaneous treatment. Mortality for this disease is approximately 10% and appears to be improving from previous early reports. However, appropriate management with antibiotics and consideration of appropriate drainage are still required for best outcomes (Fig. 22.2).

Fig. 22.2

Algorithm for treatment of pyogenic liver abscesses

Amoebic

Pathogenesis

Amoebic liver abscesses are caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica, which is endemic in tropical or developing countries. Humans are both the principal hosts and the infective carriers and the disease is usually transmitted fecal-orally. Infected cysts may be passed through water or produce contaminated with feces, foods contaminated by food handlers or by direct transmission. Most infected patients are asymptomatic but some patients will develop invasive disease of the colon. The liver is the most common extra-intestinal site for infection [16].

Once ingested, the cysts are capable of resisting acid degradation in the stomach. They are then released in the trophozoite from the cysts triggered by the neutral intestinal juice in the small intestine. Passing into the large intestine and they adhere to the colonic mucosa and invade into the tissue. These infections may manifest as mucosal thickening or more classically, as ulcerations through the mucosa and into the submucosa [17]. It is believed they cause hepatic disease by ascending through the portal system or via direct extension into the liver. Amoebic abscesses consist of three stages: acute inflammation, granuloma formation, and advancing necrosis with subsequent abscess formation. The abscess itself contains necrotic proteinaceous debris with a rim of trophozoites invading the surrounding tissue.

Since the abscess is essentially composed of blood and necrotic hepatic tissue, its appearance is typically described as anchovy sauce. It is usually odorless and sterile, unless there is secondary bacterial infection. The abscess will continue to progress and grow until it reaches Glisson’s capsule since the capsule is resistant to hydrolysis by the trophozoites. This lends to the classic imaging appearance of the lesion abutting the liver capsule (Fig. 22.3).

Fig. 22.3

A 49-year-old Chinese female who presented with RUQ pain caused by an amoebic abscess

Epidemiology

Amoebic liver abscesses usually occur in developing or tropical countries with poor sanitation systems. Areas of the world with endemic disease include Central and South America, Mexico, India, and East and South Africa. The best estimate of the prevalence of amebiasis was by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1995 that estimated approximately 40–50 million people become symptomatic per year with intestinal colitis or hepatic abscess, resulting in 40,000–100,000 deaths from the disease. A more recent population-based study in the United States identified the incidence to be 1.38 per million population with a 2.4% average decline during the course of the study (1993–2007) [16]. The mortality in that study was also lower than what has been previously reported and was approximately 1%.

Hispanic males between the ages of 20 and 40 with a history of travel to endemic regions of the world are most commonly affected by amoebic liver abscess, which is in contrast to pyogenic abscesses, which tend to occur in older patients [16]. There is also a heavier preponderance in the male gender although this is not well understood. One theory is alcohol use in men may lead to impaired Kupffer cell function or impaired immune response. Immunosuppressed patient are also at greater risk for amoebic liver abscess and predisposing conditions include HIV, steroid use, malnourished patients with severe hypoalbuminemia, and post-splenectomy patients.

Clinical Presentation

The most common clinical features of amoebic liver abscesses include fever and abdominal pain. Hepatomegaly with pain on palpation over the liver or below the ribs is one of the most important clinical signs that may help distinguish this disease from pyogenic abscesses. Other symptoms include chills, nausea, weight loss, and diarrhea. Jaundice is seen less commonly with amoebic abscesses.

Common laboratory findings include an elevated white blood cell (WBC) count and anemia. Patients with acute amoebic abscess tend to have an elevated AST and a normal alkaline phosphatase, whereas patients with chronic amoebic abscess will have a normal AST and almost always an abnormal alkaline phosphatase. In contrast, patients with pyogenic abscesses tend to have an elevated bilirubin and abnormal liver transaminases [17].

Diagnosis

Amoebic abscesses need to be distinguished from pyogenic abscesses. Like pyogenic abscesses, the majority of patient with amoebic abscesses will have an abnormal CXR, which may demonstrate an elevated hemidiaphragm, pleural effusion, or atelectasis. An abdominal ultrasound can help make the diagnosis of amoebic abscess and has an accuracy of 95%; however, it is operator dependent. Typical ultrasound findings include a round or oval lesion that is hypoechoic and homogenous in appearance without wall echoes and abutting the liver capsule. In addition the majority of lesions (>80%) are found in the right lobe of the liver.

Abdominal CT is another imaging modality that is extremely sensitive for detecting liver abscesses. Its advantage is the ability to distinguish an abscess from benign or malignant tumors; however, it does not always distinguish between pyogenic and amoebic abscess. The lesion is typically peripheral in the liver without an enhanced rim. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another imaging modality, but like CT, cannot distinguish between amoebic and pyogenic abscesses. It is also more expensive and is relatively inaccessible from an emergent standpoint.

Serologic testing is a useful adjunct to making a diagnosis of amoebic liver abscess. The majority of patients will not have any detectable parasites in their stools; however, >90% of patients will have antibodies to E. histolytica [18]. The enzyme linked immunoassay test has largely replaced all tests for E. histolytica as it is fast, highly sensitive, and widely available. Its sensitivity is ∼99% with a specificity of 90%. Although the test cannot distinguish between acute and chronic infections, it is helpful in a patient with a typical story for amoebic hepatic abscess and a mass on imaging studies for making a determination of amoebic abscess.

Treatment

Metronidazole is the treatment of choice for amoebic abscesses. The drug enters the parasite by diffusion and is converted by reduced ferredoxin or flavodoxin into reactive cytotoxic nitro radicals. A 10-day treatment of 750 mg orally three times per day has a >95% efficacy in most patients [17]. Symptomatic improvements are usually seen by 3 days of treatment and there is little, if any, resistance to the drug. If the patient is unable to tolerate metronidazole, emetine hydrochloride or chloroquine phosphate can be substituted. Emetine hydrochloride is limited in its usefulness since it is administered intramuscularly and has significant cardiac side effects. Chloroquine phosphate can be used in pregnancy and has some associated side effects such as gastrointestinal upset, headaches, and pruritis. The majority of its use is limited to recurrent or resistant hepatic amebiasis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree