180 Lithium

Lithium as a pharmacologic agent for the treatment of mania was introduced by Cade in 1949.1 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of lithium salts for treatment of mania in 1970 and for maintenance therapy of bipolar disorder in 1974.2–6 Despite the frequent occurrence of lithium intoxication, this drug continues to be used because of its effectiveness when used alone or in combination with other drugs and possibly newer indications.7–1819

The incidence of acute lithium intoxication is not known, but it has been increasing owing to the drug’s more frequent use and known narrow therapeutic index.20,21 The number of cases of toxicologic exposure to lithium reported to poison control centers in the United States grew from 5474 cases in 2004 to 6492 in 2008.20,22 Ingested lithium is excreted mainly unchanged in the urine, and chronic kidney disease is a major factor that can increase the risk of toxicity even when the drug is used as prescribed.23,21 Lithium toxicity typically occurs in one of three main settings: acute ingestion of a large dose (e.g., suicide attempt) in a patient not previously taking the drug, acute overdose in a patient chronically on the drug (frequently unintentional), or more commonly, chronic toxicity from accumulation of the drug during prescribed maintenance therapy.24 The latter problem can be avoided by a thorough understanding of conditions and drug interactions that increase the risk of lithium toxicity.24 Asymptomatic chronic lithium-induced diabetes insipidus is not acutely life threatening and is not within the scope of this chapter.25

Acute lithium intoxication causes multisystem dysfunction and irreversible neurologic deficits; it was reported fatal in 9% to 25% of patients.26,27 Early detection and treatment are critical to improve outcomes, and reported fatality rates have decreased considerably.22 This chapter emphasizes the pharmacology and physiology of lithium that underlie its toxicity and provides physicians with the foundation to effectively treat lithium intoxication.21,24

Pharmacology

Pharmacology

Lithium is a monovalent cation and, like sodium, potassium, rubidium, and cesium, a group IA alkali metal. Lithium shares some characteristics with sodium and potassium; however, differences in ionic radii among lithium (0.60 Å), sodium (0.95 Å), and potassium (1.33 Å) are responsible for the pharmacologic effects of lithium (lithium has no known physiologic role).23,28–30 For example, unlike sodium and potassium, only a small gradient for lithium can be maintained across biological membranes.

Lithium is usually administered as lithium carbonate or, less commonly, lithium citrate. In adults, the typical dose is 900 to 1800 mg/d in 3 to 4 divided doses (sustained-release preparations available). Lower doses are recommended in children and the elderly, and variations in pharmacodynamics of the drug, even in adults, make it necessary for the correct dose for each individual to be established by the clinician.31,32 A dose of 300 mg lithium carbonate contains 8.12 mEq lithium ion. After oral administration, lithium is readily absorbed, with complete absorption occurring at approximately 8 hours and peak levels at 1 to 2 hours for the standard-release dosage forms or 4 to 5 hours after ingestion for the sustained-release forms.21 Lithium is not protein bound; it distributes freely in total body water and accumulates in various tissues, with the exception of cerebrospinal fluid. In the steady state, the volume of distribution for lithium is 0.7 to 0.9 L/kg (Table 180-1). Lithium concentration in cerebrospinal fluid is 40% of the plasma level21,33 as a result of transport of lithium out of the cerebrospinal fluid by brain capillary endothelium, arachnoid membrane, or both.34

TABLE 180-1 Pharmacology of Lithium

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Molecule | Monovalent cation; radius 0.6 Å; weight 7 D |

| Dose (adult) | 900-1800 mg/d in 3-4 doses (less in sustained-release form) |

| Therapeutic serum level | 0.7-1.2 mEq/L (Some clinicians now aim for 0.6-0.8 mEq/L, especially when used in combination with other agents.) |

| Toxic levels | >1.5 mEq/L (narrow therapeutic index) |

| Bioavailability | >95% |

| Volume of distribution | 0.7-0.9 L/kg in steady state |

| Half-life | 12-27 hours after single dose (longer with chronic therapy, chronic kidney disease, and in elderly patients) |

| Time to peak plasma level | 2-4 hours after ingestion |

| Elimination | Primarily renal; excreted unchanged in urine |

Historically, the therapeutic level of lithium was considered to be between 0.7 and 1.2 mEq/L, but clinicians are now targeting a level of 0.6 to 0.8 mEq/L, because toxicity is associated with levels above 1.5 mEq/L. The plasma elimination half-life of a single dose is between 18 and 36 hours.21 Elimination takes longer in the elderly; in these patients, the half-life can be as long as 36 hours.35 Elimination half-life also varies with duration of therapy36; it may be considerably longer in patients who have been treated with lithium for a long time. The longer half-life is caused by intracellular accumulation and inhibition of lithium efflux after chronic lithium therapy. Thus it is important to know that lithium has a very narrow therapeutic index, and the patient’s age and duration of therapy may affect elimination half-life.

Approximately 95% of a single dose of lithium is excreted unchanged in the urine; only trace amounts are found in feces.37 Lithium is not bound to proteins and therefore is freely filtered by the glomerulus; 80% of the filtered load of lithium is reabsorbed, and 20% is excreted in urine.38 Renal lithium clearance in normal individuals is 10 to 40 mL/min38–40; the fractional lithium clearance is estimated to be 0.17 to 0.29.38,40,41

Because lithium clearance is proportional to the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), factors affecting the GFR have significant influence on the clearance of lithium. Substantial reductions in lithium dosage must be made in patients with chronic kidney disease. Furthermore, alterations in the proximal reabsorption of lithium can alter the fractional excretion of lithium without significantly affecting GFR. This characteristic of renal lithium handling has important therapeutic implications. Drugs known to inhibit proximal reabsorption of lithium can increase the fractional excretion of lithium and thereby increase lithium removal. Diuretics that alter proximal reabsorption of sodium (e.g., acetazolamide, aminophylline, urea) increase fractional excretion of lithium,38 whereas other diuretics (e.g., thiazides, ethacrynic acid, spironolactone) act distal to the proximal tubule and have no effect on fractional excretion of lithium.41 These results suggest that the primary site of lithium reabsorption is in the proximal tubule.

Lithium Toxicity

Lithium Toxicity

Patients with lithium intoxication exhibit a variety of clinical manifestations. The severity of symptoms frequently is proportional to the degree of elevation of serum lithium levels.42 However, symptoms do not always correlate with lithium levels, because symptoms of toxicity have occurred at therapeutic levels,28,30,43–45 and minimal symptoms have resulted from high levels.28,46 In general, however, serum lithium levels of 1.5 to 2.5 mEq/L at 12 hours after the last dose of lithium usually are accompanied by slight or moderate symptoms of intoxication, values of 2.5 to 3.5 mEq/L should be regarded as serious, and values greater than 3.5 mEq/L are life threatening.28

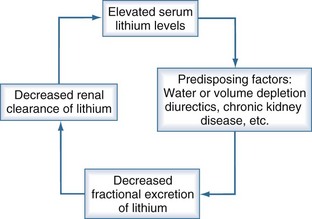

The patient’s history often reveals associated conditions predisposing to lithium toxicity (Box 180-1). Factors that predispose to toxicity include advanced age,47 schizophrenia, preexisting brain damage,48 and rapid rise of serum concentration after an acute overdose. Other conditions such as diarrhea, vomiting, inadequate fluid therapy after surgery, diuretics, and volume depletion are associated with states of sodium depletion. Because sodium balance affects the clearance of lithium,38,49–51 decreased dietary sodium intake52–55 and chronic therapy with furosemide or a thiazide diuretic51,56–61 are situations associated with lithium intoxication. These conditions often result in a vicious circle that potentiates lithium toxicity (Figure 180-1).

A number of drugs are associated with acute lithium toxicity (Table 180-2). Lithium toxicity has been reported with the concomitant use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including cyclooxygenase II inhibitors.62–76 Patients with congestive heart failure and volume depletion who depend on endogenous prostaglandin synthesis to maintain renal blood flow and GFR are more susceptible to lithium toxicity when they take NSAIDs. In these patients, prostaglandin synthesis inhibition by NSAIDs can markedly reduce GFR and lithium clearance, causing significant lithium toxicity. Long-acting angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors77 and angiotensin receptor blockers78–85 decrease GFR and fractional excretion of lithium,38 thereby predisposing patients to lithium toxicity.

TABLE 180-2 Known Drug Interactions of Lithium

| Drug | Effect on Serum Lithium Levels |

|---|---|

| Diuretics: | |

| Thiazides | Increase |

| Loop diuretics | Decrease |

| Osmotic diuretics | Decrease |

| Potassium sparing | Decrease |

| Methyl xanthine | Decrease |

| Acetazolamide | Decrease |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Increase |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | Increase |

| Phenothiazines | Increase |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: | |

| Indomethacin | Increase |

| Ibuprofen | Increase |

| Mefenamic acid | Increase |

| Naproxen | Increase |

| Sulindac | None |

| Aspirin | None |

| Cyclooxygenase II inhibitors | Increase |

| Tetracycline | Increase |

| Cyclosporine | Increase |

| Fluoroquinolones | Increase |

Modified from references 125-128.

Clinical Features of Lithium Toxicity

Patients with lithium toxicity present with a variety of clinical manifestations (Box 180-2). Neurologic symptoms are predominant.27 Central nervous system symptoms often develop gradually, starting initially with confusion and progressing to impaired consciousness, coma,27,86 and occasionally death.87 Cerebellar manifestations are often prominent and can include dysarthria,88 truncal ataxia, broad-based ataxic gait, nystagmus, and varying degrees of incoordination. Other central nervous system manifestations of lithium intoxication are seizures86–90 and involvement of the basal ganglia, as suggested by choreiform movements48,91,92 and Parkinson’s disease–like movements.93

Gastrointestinal side effects of lithium therapy include gastric irritation, epigastric bloating, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.94 Although these are common findings, gastrointestinal complaints are not prominent manifestations of lithium intoxication.27

Electrocardiographic changes are frequently associated with lithium therapy.94 Lithium intoxication can be associated with transient ST-segment depression or inverted T waves in leads V4-6.27 Although electrocardiographic changes are common, cardiac symptoms are rarely manifestations of lithium intoxication. Sinus node dysfunction has been reported to be a consequence of lithium intoxication leading to syncope.95,96

Polyuria and polydipsia are frequent side effects of lithium therapy; they are estimated to occur in 20% to 70% of patients.3 The concentrating defect may develop not only in patients who are overtly toxic but also in those with therapeutic levels.3 Polyuria may lead to volume depletion and decrease the fractional excretion of lithium. The mechanisms responsible for lithium-induced polyuria were summarized by Singer3; they include primary polydipsia, central diabetes insipidus, and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.

Other less common manifestations of lithium intoxication are hyperthermia,97 hypothermia,98 peripheral neuropathy,99,100 myopathy,101 and severe leukopenia.102

Treatment

The initial management of lithium intoxication is determined by the degree of intoxication (serum level), a history of acute versus chronic lithium exposure, the clinical symptoms, and the adequacy of renal function.103 As noted in Table 180-2, patients present with a variety of clinical manifestations, from chronic lithium therapy to acute overdose. Those who appear to have severe impairment of consciousness require airway protection and admission to an intensive care unit. Activated charcoal is an ineffective gastrointestinal decontaminant in lithium overdose because it does not absorb strongly ionized chemicals. In contrast, polyethylene glycol (CoLyte, GoLYTELY) has been shown to be effective in acute lithium intoxication.104 Sodium polystyrene sulphonate has been used only in cases of chronic stable lithium toxicity with serum levels of no more than 2.3 mEq/L.105

Volume status should be assessed because significant volume depletion can occur as a result of urinary concentrating defects. Many of these patients have volume-responsive decreases in renal function.27 Therefore, fluid resuscitation is critical in the initial management. Administration of large volumes of isotonic saline should be done carefully because severe hypernatremia has been associated with such fluid management.27,42,92,106,107 After fluid resuscitation, efforts to enhance lithium removal are the next step. Various modalities for lithium removal are listed in Table 180-3. The efficacy of each modality in removing lithium can be assessed by comparing lithium clearance values. Because there are no controlled studies of lithium clearance during intoxication, the following data on lithium clearance rely heavily on case reports.

| Mode | Lithium Clearance (mL/min) |

|---|---|

| Renal excretion | 10-40 |

| Forced diuresis | 0.9-39 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 9-15 |

| Hemodialysis (blood flow, 126-250 mL/min) | 70-170 |

| Continuous renal replacement therapies | Variable, about 20.5 |

In normal individuals, renal lithium clearance is about 10 to 40 mL/min.38–40 Hansen and Amdisen27 reported that renal lithium clearance is 0.9 to 18.4 mL/min in patients with lithium intoxication. Of the 23 patients studied by these authors, only 5 had normal renal function (i.e., creatinine clearance > 78 mL/min). Therefore, in patients with lithium intoxication, the ability to remove lithium by renal excretion can be limited by poor renal function.

Because 80% of lithium is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule, factors that decrease proximal lithium reabsorption can increase lithium clearance, enabling enhanced lithium removal during states of intoxication. Because sodium balance alters the clearance of lithium,49–51108 forced diuresis with isotonic saline has been used as a treatment of lithium intoxication. Because consistent therapeutic benefits have not been achieved with forced diuresis27,109 and because of the potential for hypernatremia, forced diuresis is not recommended for severe lithium intoxication.27,35 However, if lithium clearance is impaired as a result of volume contraction, administration of isotonic saline may increase lithium clearance transiently.

The effects of various agents on the clearance of lithium have been studied in humans challenged with a single dose of lithium.38 Whereas water loading, furosemide, thiazide diuretics, ethacrynic acid, ammonium chloride, and spironolactone did not increase clearance of lithium, sodium bicarbonate, acetazolamide, urea, and aminophylline were effective. Clinical studies employing these agents for lithium removal during intoxication have not been reported.

Peritoneal dialysis is another means of lithium removal. Wilson and coworkers,110 using 2-L exchanges per hour, attained clearances of 13 to 15 mL/min. Similar results were achieved by O’Connor and Gleeson,109 who reported lithium clearances of 9 mL/min with frequent 2-L exchanges. Although peritoneal dialysis is no more efficient in removing lithium than forced diuresis, it avoids problems associated with intravenous administration of large volumes of isotonic saline.

Conventional hemodialysis remains the mainstay of therapy in severe lithium intoxication.111 The decision to use hemodialysis (or other extracorporeal therapies) should be made by the nephrologist in consultation with the intensivist and not be expected to come from the poison control centers, because specific factors other than serum lithium levels are not always evident to staff at the local poison control center.112

Lithium is one of the most readily dialyzable toxins because of its small atomic weight and negligible protein binding. Several reports indicate lithium clearances between 70 and 170 mL/min with hemodialysis.27,113,114 Because lithium clearance is almost proportional to blood flow, increasing the blood flow to more than 300 mL/min can further enhance clearance. Table 180-3 compares lithium clearance by various modalities, showing the superiority of hemodialysis to other traditional methods.

The duration of hemodialysis should be guided by serial measurements of serum lithium levels. When levels approach therapeutic range, dialysis may be terminated; however, subsequent hemodialysis may be necessary because serum levels may rise after termination of hemodialysis.27,103,114 This rebound effect occurs as a result of continued absorption of lithium from the gastrointestinal tract, delayed release from long-acting preparations, and redistribution of lithium from intracellular stores.103 Although serum lithium clearance has been reported to range from 70 to 170 mL/min,110,113 the extraction or clearance of lithium from intracellular stores, as reflected by red blood cell clearance, is only 10 to 13 mL/min.113 This slower extraction of lithium from intracellular stores contributes to the rebound effect.

Continuous renal replacement therapy (e.g., continuous arteriovenous hemodiafiltration, continuous venovenous hemofiltration) has been used either as an alternative to conventional hemodialysis or in addition to conventional hemodialysis.111,115–119 The combination of conventional hemodialysis followed by continuous renal replacement therapy is very useful for preventing the rebound phenomenon.103,111,116,117

Box 180-3 summarizes the management of lithium intoxication. Initially, the degree of consciousness and volume status should be assessed. The airway should be protected if necessary, and isotonic saline should be administered for volume repletion. After these critical maneuvers, management should focus on lithium removal. The method of lithium removal is determined by the degree of elevation of the serum lithium concentration, severity of symptoms, and duration of intoxication. Although each patient should be evaluated individually, rough guidelines with rational therapeutic options can be derived from knowledge of the pharmacokinetics of lithium removal. For those patients with minimal symptoms, normal renal function, and mild elevation of serum lithium levels (<2.5 mEq/L), intravenous hydration may be adequate. Urinary electrolytes should be evaluated as a guide to the type of replacement fluid used. This approach avoids hypernatremia, which commonly occurs with forced diuresis. For severe lithium intoxication, hemodialysis is clearly superior to other modalities. Peritoneal dialysis or continuous arteriovenous hemofiltration may be used if hemodialysis is unavailable.

Box 180-3

Management of Lithium Intoxication

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree